Some Common Logical Fallacies

advertisement

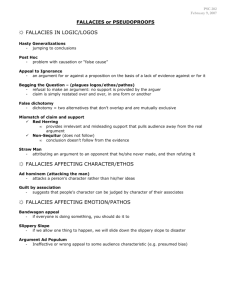

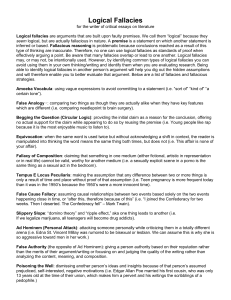

AP Language and Composition—Kennett COMMON LOGICAL FALLACIES Learning Target: Students will understand and be able to identify logical fallacies to improve their own logical arguments and spot other people’s fallacious arguments Overview Component Fallacies: Errors in process of reasoning 1. Undistributed middle 2. Either-or reasoning 3. Hasty Generalization 4. Slippery slope 5. Straw Man 6. Red Herring 7. False Cause / Post hoc 8. False Analogy 9. Begging the question & Circular Reasoning Fallacies of Relevance: Using evidence or examples that are irrelevant to the issue 10. Ad hominem 11. Bandwagon 12. Genetic Fallacy 13. Appeal to pity 14. Appeal to improper authority Fallacies of Ambiguity: Errors due to unclear words or phrases 15. Equivocation 16. Division Fallacies of Omission: Material is simply left out 17. Stacking the deck 18. Appeal to ignorance Component Fallacies: Errors in the process of reasoning 1. Undistributed Middle: This is when the subject of a syllogism’s major premise – or “middle term” -- is not properly distributed in both premises. To understand why this is a problem, you must understand the proper construction of a syllogism. A proper syllogism distributes the subject of the major premise in both premises. For example, the following proper syllogism has the subject of the major premise “PR Teachers (A)” in both premises: Major Premise: All PR teachers (A) are amazing (B). Minor Premise: Kennett (C) is a PR teacher (A). Conclusion: Kennett (C) is amazing (B). Example 1: All snails are cold-blooded. All snakes are cold-blooded. All snails are snakes. (Problem: The subject of the major premise, “snails,” is not even in the second premise.) Example 2: Most Arabs are Muslims. All the 9/11 hijackers were Muslims. Most Arabs are hijackers. (Problem: The subject of the major premise, “Arabs,” is not even in the second premise.) Example 3: All 6-year-olds enjoy TV. All teenagers enjoy TV. All 6-year-olds are teenagers. (Problem: The subject of the major premise, “6-year-olds,” is not even in the second premise.) 2. Either-Or Reasoning / False Dichotomy: The argument fails because the speaker/writer presents there are only two choices or possible outcomes when there may in fact be several. Example 1: Either we must ban phones or Prairie Ridge culture will collapse. Example 2: Either you drink Pepsi Cola, or you will have no friends and no social life. 2 Tip: Examine your own arguments: If you're saying that we have to choose between just two options, is that really so? Or are there other alternatives you haven't mentioned? If there are other alternatives, don't just ignore them— explain why they, too, should be ruled out 3. Hasty Generalization: Making assumptions about a whole group or range of cases based on a sample that is inadequate (usually because it is atypical or just too small). Example 1: Stereotypes about people ("frat boys are drunkards," "grad students are nerdy," etc.) Example 2: My roommate said her philosophy class was hard, and the one I'm in is hard, too. All philosophy classes must be hard!" (Problem: Two people's experiences are, in this case, not enough on which to base a conclusion.) Tip: Consider whether or not you have data from enough people to make a conclusion. Don’t make stereotypes or broad sweeping conclusions. (Notice that in example 2, the more modest conclusion "Some philosophy classes are hard for some students" would not be a hasty generalization.) 4. Slippery Slope: The speaker argues that if the first step is taken, a second or third step will inevitably follow, much like one step on a slippery hill will have you sliding down to the bottom. It argues that there will be one big chain reaction when in fact that’s not necessarily the case. Example: If we allow the government to infringe upon our right to privacy on the Internet, it will then feel free to infringe upon our privacy on the telephone. After that, FBI agents will be reading our mail. Then they will be placing cameras in our houses. We must not let any governmental agency interfere with our Internet communications, or privacy will completely vanish in the United States. Tip: Check your argument for chains of consequences, where you say "if A, then B, and if B, then C," and so forth. Make sure these chains are reasonable. 5. Straw Man: Any attempt to “prove” an argument by overstating, exaggerating, or oversimplifying the arguments of the opposing side. The name comes from the idea of a boxer or fighter fashioning a false opponent out of straw, like a scarecrow, and then knocks it over in the ring before an admiring audience. Example: Tennessee should increase funding to unemployed single mothers during the first year after childbirth because they need sufficient money to provide medical care for their newborn children." His opponent retorts, "My opponent believes that some parasites who don't work should get a free ride from the tax money of hard-working honest citizens." (Problem: In this example, the opponent is distorting the speaker's statement about medical care for newborn children into an oversimplified form so he can more easily appear to "win.") Tip: Be charitable to your opponents. State their arguments as strongly, accurately, and sympathetically as possible. If you can knock down even the best version of an opponent's argument, then you've really accomplished something. 6. Red Herring: A deliberate attempt to change the subject or divert the argument from the real question at hand to some random side-point. The name comes from a stinky fish that hunting-opponents used to detract hunting dogs from the scent of foxes. The dogs would lose the scent of the fox and follow the path of the herring. 3 Example1: Senator Jones should not be held accountable for cheating on his income tax. After all, there are other senators who have done far worse things. (Problem: The question at hand is whether or not the senator should be held accountable for cheating on taxes, not what others have done.) Example 2: I should not pay a fine for reckless driving. There are many other people on the street who are dangerous criminals and rapists, and the police should be chasing them, not harassing a decent tax-paying citizen like me.” (Problem: The questions at hand are (1) did the speaker drive recklessly and (2) should he pay a fine for it, not (3) are there worse criminals out there?) Tip: Ensure that the issues you bring up are all truly logically related. 7. False Cause / Post Hoc: This wrongly assumes that because B followed A, A caused B. “Post hoc” refers to a Latin phrase “post hoc, ergo propter hoc,” which means “after this, therefore because of this.” Example 1: A black cat crossed my path at noon. An hour later, my mother had a heart-attack. Because the first event occurred earlier, it must have caused the bad luck later. Example 2: After playing violent video games, the student punched his friend. Therefore, the videogames caused the student to punch his friend. Tip: If you say that A causes B, you should have something more to say about how A caused B than just that A came first and B came later! 8. False or weak analogy: Relying on weak comparisons to “prove” a point rather than arguing with more data and deduction. Example 1: Education is like cake; a small amount tastes sweet, but eat too much and your teeth will rot out. Likewise, more than two years of education is bad for a student. Example 2: Guns are like hammers—they're both tools with metal parts that could be used to kill someone. And yet it would be ridiculous to restrict the purchase of hammers—so restrictions on purchasing guns are equally ridiculous. (Problem: While guns and hammers do share certain features, these features (having metal parts, being tools, and being potentially useful for violence) are not the ones at stake in deciding whether to restrict guns.) 9. Begging the question & circular reasoning: These two fallacies are very similar. First, begging the question is when an arguer proposes an idea and assumes it to be true without any proof being provided. In a much more obvious way, circular reasoning is when an arguer tries to prove a position by restating it in different words. Example 1 – Begging the Question: Suppose a local university holds a student senate meeting in order to discuss the cancellation of certain English courses. A particular student group states, "Useless courses like English 101 should be dropped from the college's curriculum," and goes on to illustrate that spending money on a useless course is something nobody wants. Those students beg the question by never proving that English 101 was itself a useless course. Example 2 – Circular Reasoning: President Reagan was a great communicator because he had the knack of talking effectively to the people. 4 Fallacies of Relevance: Using evidence or examples that are irrelevant to the issue at hand. 10. Ad hominem & Tu Quoque: Both of these fallacies personally attack on the opponent rather than an accurate argument against the opponent’s position. In Latin, “ad hominem” means “against the person” and directly attack the person’s character rather than his position. “Tu quoque” is Latin for “You too” and is when an opponent claims a person’s point is invalid because he’s a hypocrite and has done the very thing he claims you shouldn’t do. Example – ad hominem: This candidate’s policies are dead wrong and can’t be trusted. Just look at all of his unpaid parking tickets! How can we trust the policies of such an irresponsible man?! Example – tu quoque: Why should I believe your reasons not to smoke – you smoked in 5 years ago! 11. Bandwagon / Ad populum: Arguing that something is right because of the sheer volume of people that believe it. “Everybody’s doing it!” Example: 85% of consumers purchase Dell computers rather than Mac; all those people can't be wrong. Dell must make better computers. Tip: Popular acceptance doesn’t prove something’s valid. Use facts related to your argument, no sheer popularity. 12. Genetic Fallacy: Rejecting an argument based on its origins rather than on its own merits. A related form accepts or rejects arguments based on others who endorse or reject those same arguments. Example 1: You think labor unions are good? You know who else liked labor unions? Karl Marx, that’s who! (Problem: The argument rejects labor unions on the grounds that Marx liked unions without making any reference to any of the present arguments for or against labor unions.) Example 2: You're not going to wear a wedding ring, are you? Don't you know that the wedding ring originally symbolized ankle chains worn by women to prevent them from running away from their husbands? I would not have thought you would be a party to such a sexist practice. (Problem: There may be reasons why people may not wish to wear wedding rings, but it would be logically inappropriate for a couple to reject the notion of exchanging wedding rings on the sole grounds of its sexist origins.) 13. Appeal to Pity: While pathos generally works to reinforce an idea, if a writer only uses emotion as a support for his point without logical data, it’s insufficient. Example: Come on, Kennett! You need you to let me turn in this late paper without a penalty. I’ve been having a really bad day – my goldfish died, I think I’m starting to get sick, and I tripped while walking down the hall. Letting me turn in my paper would make me really happy! (Problem: You haven’t yet provided a valid excuse for why your paper is late; you’re just trying to make me feel bad for you. Nice try, though!) 14. Appeal to improper authority: While it’s not fallacious to appeal to a credible authority, this is an appeal to a famous person our source that may not be reliable. It attempts to capitalize on feelings of respect or familiarity with a famous individual. Example: I’m not a doctor, but I play one on TV and when many adults get sick, they too play doctor at home. Don’t play doctor – take Vicks cough syrup. 5 Fallacies of Ambiguity: Errors due to ambiguous words or phrases 15. Equivocation: sliding between two or more different meanings of a single word or phrase that is important to the argument. Example 1: A feather is light. What is light cannot be dark. Therefore, a feather cannot be dark. (Problem: While this appears to be correct as a syllogism, the meaning of “light” changed.) Example 2: Giving money to charity is the right thing to do. So charities have a right to our money." (Problem: The equivocation here is on the word "right": "right" can mean both something that is correct or good (as in "I got the right answers on the test") and something to which someone has a claim (as in "everyone has a right to life")) Tip: Use the words in your argument correctly and consistently. 16. Division: This falsely claims that what is true of the whole must be true of the individual parts. Example 1: Microtech is a company with great influence in the California legislature. Egbert Smith works at Microtech; he must have great influence in the California legislature. (Problem: This is not necessarily true. Egbert – what an awesome name – may work the graveyard shift as a security guard or as a copy-machine repair guy, positions that have no interaction with the state legislature.) Example 2: Sunsurf is a company that sells environmentally safe products. Susan Jones is a worker at Sunsurf. She must be an environmentally minded individual. (Perhaps she is motivated by money alone?) Fallacies of Omission: Material is simply left out 17. Stacking the Deck: Similar with straw man, where an opponent portrays a rival argument in a negative light by presenting an inaccurate portrayal of the argument to tear it apart, here a speaker "stacks the deck" in his favor by ignoring examples that disprove the point, and listing only those examples that support his case. Example: The stereotypical “used car salesmen” stacks the deck by raving about a car’s reliability, but after you decide to buy the car they may turn around and try to sell you the extended warranty — in case the car breaks down! 18. Appeal to Ignorance: Since one cannot disprove a claim, it must be true. Example 1: You have no evidence to prove that UFOs don’t exist, so they must exist! They’re out there! (This is fallacious. The inability to disprove something doesn’t make it true.) Example 2: In spite of all the talk, not a single flying saucer report has been authenticated. We may assume, therefore, there are not such things as flying saucers. (This is also fallacious. We still don’t have proof either for or against the existence of UFOs.)