RRP Final Draft Kenny Nelson - 2010

advertisement

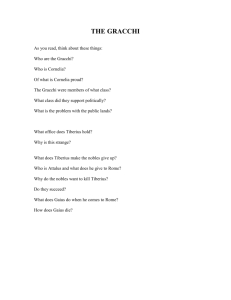

Nelson 1 Kenneth Nelson English 10 Ms. Burgan November 10, 2010 The Gracchi A man who gives his life for the good of the people, how does one describe this person? This person is a man of the people. He is a man who pits himself against a fearsome power to help his peers and is prepared to die for them. Gaius and Tiberius Gracchus pitted themselves against the senate to benefit the people. They faced the un-just consequences for their actions, but made sure their Lex Agraria land reforms were set in stone. The Gracchi brothers were working for the people in their early political careers. They gained support for themselves by their noble actions and they were renowned for their energetic speaking ability. Their family had good political connections throughout the government, and they were respected because of their powerful methods of oration. Plutarch examines these differences when he writes: “In the second place, the speech of Caius was awe-inspiring and passionate to exaggeration, while that of Tiberius was more agreeable and more conducive to pity. The style also of Tiberius was pure and elaborated to a nicety, while that of Caius was persuasive and ornate.” (Plutarch 149). Nelson 2 Plutarch explains how they gained support and influence by their amazing ability to persuade Roman crowds. In 137 BC, Tiberius Gracchus was appointed Quaestor under Gaius Manicus in the Numantine war. Due to Manicus’s terrible strategic ability, his entire force could do nothing to prevent itself from being surrounded by the enemy. Tiberius boldly stood up to his superior officer and used his voice to persuade the enemy to negotiate a peace treaty that would give them no hostages. When the soldiers returned to Rome, the Senate was fuming over the disregard for the image of Rome, despite the number of soldiers spared. Tiberius’s actions were considered to be in opposition to the principles of Rome, and Tiberius was forced to rely on his brother in law, Scipio Aemilianus, to prevent the Senate from confiscating his political power. Even though Scipio was able to ward off the senate from Tiberius, his actions were very unsettling to them and would be used against him later, despite his obvious intentions behind them. Keith Richardson elaborates the negative aspect of this support when he writes “Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus lost any support from the senate when they were elected Plebian Tribunes by their loyal supporters.” (Richardson 71) They were illegally appointed Tribune of the Plebs and negotiating a peace was not helping their cause with the senate. Having loyal supporters was an advantage. This advantage was especially useful later when they bypass the Senate and instigated the Lex Agraria. Stockton notes that the urban poor were a major problem for Rome when he states “These reforms were necessary to the life of Rome. Without them, bands of thugs would have caused panic among the streets of Rome, and a dark period of its history would have gone unrecorded.” (Stockton 68) This tells us just how necessary these reforms were to the life of Rome. Nelson 3 Without a lower working class, nobody was buying anything, and slaves from the numerous wars were the primary source of labor. The estates of the wealthiest Romans were getting larger and harder to defend. Historians understand the nature of the Lex Agraria due to this identification made by Plutarch: “Of the territory which the Romans won in war from their neighbors, a part they sold, and a part they made common land, and assigned it for occupation to the poor and indigent among the citizens, on payment of a small rent into the public treasury. And when the rich began to offer larger rents and drove out the poor a law was enacted forbidding the holding by one person of more than five hundred acres of land. For a short time this enactment gave a check to the rapacity of the rich, and was of assistance to the poor, who remained in their places on the land which they had rented and occupied the allotment which each had held from the outset.” (Plutarch 161). This gave land to the urban poor and allowed them to raise money and/or join the Roman army, as well as pay taxes to the Roman government. This reduced the social divide according to O’Grady when he writes “A clear social divide was seen during this period, one that could have only been bridged by the Law of Agraria.” (O’Grady 151) This angered the senate and wealthier Romans by attacking their sense of entitlement, and reducing their vast estates to make room for Roman citizens. These laws were passed not by the senate, but by the Tribune of the Plebs, insulting the senators that might have supported it and angering the ones who wanted to be represented by voting against it. The Agrarian laws accomplished five main interests. First, it gave money to the urban poor. Second, it provided soldiers for the diminished Roman army. Third, it created new Nelson 4 taxpayers for the Roman government. Fourth, it reduced the gap between the social classes. Fifth, it fixed the Roman economy and put the hearts of many terrified Roman citizens to rest. These laws caused anger from the senate toward the Gracchi. Putting their lives on the line in order to resolve the issues of the people shows just how devoted the Gracchi were to their cause. Some historians suggest that the Gracchi brothers went too far by angering the senate. A measure that was taken by both of the Gracchi to ensure their political footing and allow them to spread their message to the people was the illegal nomination and later, election to the office of Tribune of the Plebs. Gaius and Tiberius Gracchus were both patricians, and had no authorization by the Senate to put themselves in that position. The possible outrage of the people was enough to place them in that office, and even more popular support allowed for the position to be used in such a way that it had never been used before. Another altercation that came from the senate was due to the extended terms conducted by both Gracchi. They were the first politicians in a long line of Tribunes that had served more than one term in a row, and the senate was starting to fear that the Gracchi wanted to be kings. This possibility that lingered in the minds of the senators would be supported by some of their later actions, but at that point is still contributed to their fear and loathing of the Gracchi. Plutarch tells readers of the anger and confusion caused by the Gracchus brothers actions by stating ”The aristocrats, however, who were vexed at these proceedings and feared the growing power of Tiberius, heaped insult upon him in the senate.” (Plutarch 175) This statement by Plutarch shows that at that point, the senate had become so filled with antipathy towards Tiberius and Gaius that they no longer concealed their insults like daggers, but rather thrust them openly in impertinence to their being. Nelson 5 Tiberius bypasses or forces the senate to pass his legislations on numerous occasions. Richardson tells us this in his book by stating that: “Tiberius ignored the senate and brought his statement to the Plebian Court, otherwise alienating those few senators who would have otherwise supported him. This led to heated debate among the senators as to the implications of his actions.” (Richardson 106) Some of his earlier reforms the senate refused to even vote on, and this infuriated Tiberius. He then used his political power to shut down all business that was conducted daily in the forum which caused many people to riot in opposition to the senate. This gave the senate no other choice than to pass the delegation of the earlier reforms that increased the power of the Tribune of the Plebs and reduced the power of the senate. The Gracchi made an enemy out of the senate when they forced the Roman Senators to hand over their power. O’Grady states in reference to the senate that”Who would have stood for such actions against themselves?” (O’Grady 151) O’Grady relates the emotional strife held by the senate due to the Gracchi’s actions. Actions, words, reforms, and popular support led to the reaction of the senate. These reactions were earthshaking and brutal, but they helped to allow the agrarian reforms last until the time of Sulla (50BC). Plutarch depicts the death of Tiberius in the passage: “Now, the attendants of the senators carried clubs and staves which they had brought from home; but the senators themselves seized the fragments and legs of the benches. As he strove to rise to his feet, he received his first blow, as everybody admits, from Publius Satyreius, one of his colleagues, who smote him on the head with the leg of a bench; to Nelson 6 the second blow claim was made by Lucius Rufus, who plumed himself upon it as upon some noble deed. And of the rest more than three hundred were slain by blows from sticks and stones, but not one by the sword.” (Plutarch 191) Plutarch depicts the gruesome death of this man that shows how Tiberius remained steadfast even to his death because he was devoted to his cause. The senate, fearing a civil war and seeing the amount of support that the Gracchi had even after death, allowed the reforms to remain in place and elected a successor to the Populars. Plutarch illustrates this by stating: “But the senate, trying to conciliate the people now that matters had gone too far, no longer opposed the distribution of the public land, and proposed that the people should elect a commissioner in place of Tiberius. So they took a ballot and elected Publius Crassus, who was a relative of Gracchus; for his daughter Licinia was the wife of Caius Gracchus.” (Plutarch 195) The Gracchi, loved by the people and feared by the senate, gave their lives to their cause. The senate, seeing this, bent their heads in reconciliation, and allowed their legislations to remain. The Gracchi were men of the people indeed. They fought hard against the Roman Senate to help the people of Rome, and gave their lives to further their cause. They gathered political support through noble deeds and by persuasion. They created laws that solved many of Rome’s issues. They put themselves at odds against the great power of the senate. They gave their lives and did not act selfishly in the face of death. What more could be asked from such men of the people? Nelson 7 Works Cited O'Grady, Standish. "Tiberius Gracchus." All Ireland Review 2 (1901): 151. Print. Plutarch, Lucius. Makers of Rome: Nine Lives. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1965. Print. Richardson, Keith. Daggers in the Forum: The revolutionary lives and violent deaths of the Gracchus brothers. London: Cassell, 1976. Print. Stockton, David. The Gracchi. New York: Oxford University Press, USA, 1979. Print.