File

advertisement

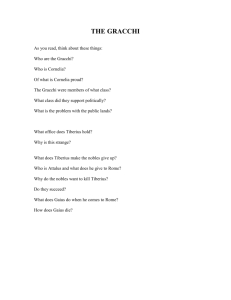

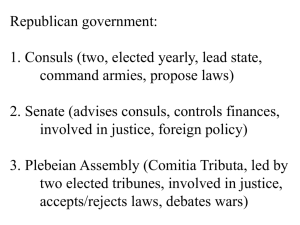

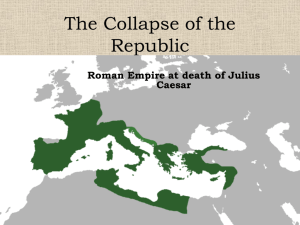

The Gracchi By Michael Frolek Turner Aristocratic Class Senatorial order ~ Furnished members of the Senate; hugely wealthy and powerful. Equites ~ Thus named for the requirement that a member must have sufficient wealth to own a horse; largely composed of particularly well-to-do businessmen. Poor Non optimo iure The Mob ~ Those who lived in the city, largely tradesmen and artisans, and lived off populist government handouts and whatever they could earn themselves. Farmers ~ Those who lived outside of the city, often desperately poor as they lacked land to farm. Latin colonists ~ Those who lived on conquered land with few political rights. Provincials ~ Someone native to conquered land; occasionally went untaxed but completely without legal right. Slaves THE GRACCHI The Gracchi came from a wealthy and influential plebeian sub-family of the gens Sempronia. Tiberius and Gaius’ great-grandfather (also Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus) served as consul in 238 BCE. Their great-uncle (another Tiberius Sempronius) also twice served as consul. The brothers’ father, Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus the Elder, served as praetor, censor, and consul. Agricultural Law Ager publicus ~ Land conquered in war that was held by the state. Initially, laws stated that a citizen could only hold up to 300 acres of the public land. These laws were ignored and the rich forced out the poorer farmers. Use of slave labour Slaves were used to farm the massive landholdings of the rich, meaning that the people who had lost their farms were unable to make a wage working someone else’s land. Tribune of the Plebs The tribune of the plebs acts as the president of the Plebeian Council, a legislative body somewhat analogous to the Commons. As such they could veto actions on behalf of the plebeians. The lives and persons of tribunes were sacrosanct, the violation of this sacrosanctity was not only a secular offense but a religious one and the violator was immediately viewed as an outlaw who could be killed without penalty. The sacrosanctity of the tribune protected the tribune from prosecution. Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus Born 163-162 BC Prior to his career in politics Tiberius had a distinguished military career, where he was recorded as being the first to scale enemy walls at Carthage. It is said that when Tiberius was in Etruria (an area of land that comprises most of what is now Tuscany) he was outraged to see the lands worked by slaves while the free people were unemployed. Agrarian reforms Tiberius was elected tribune of the plebs in 133 BCE. Tiberius believed that most of the problems with poverty could be solved by the fair redistribution of public land. Tiberius proposed to limit an individual holding of ager publicus to 300 acres, that the previous holders be compensated for any improvements they may have made, and the land be redistributed fairly and legally. While this was a legal act as the ager publicus was owned by the state, many of the landholders who had held the land for many years felt it was tantamount to theft. Almost immediately a conflict arose between supporters of Tiberius and the Senate. Illegal acts In order to block Tiberius’ reforms the senators persuaded another tribune, named Marcus Octavius, to veto the bill. It is important to note that this act, while ethically dubious, was not illegal. Tiberius’ response was to call for Marcus Octavius to be removed from office and an election called, within Octavius’ term. There was no law that allowed such proceedings to take place, but Tiberius used popular opinion to depose Octavius and pass his law. More law-breaking The senators determined that the moment Tiberius’ term ended they would prosecute Tiberius for his illegal act. To avoid prosecution Tiberius ran for a second consecutive term as tribune, though a ten-year interval was required between terms as tribune. These acts polarized the government, with the senate calling Tiberius a traitor and the people calling him a patriot. The Fall of Tiberius On the day of the election, after a series of almost absurd mistakes, a group of senators appeared in the Forum, lead by Scipio Nasica and armed with clubs, and beat Tiberius and 300 of his supporters to death. Ironically, Scipio Nasica’s father was Tiberius the Elder’s brother-in-law, who’d been forced to resign his consulship as collateral of Tiberius the Elder’s political maneuvering. The murder of a tribune, even one who had committed crime, was a controversial act, and to placate public opinion, the Senate did in fact enforce many of the Gracchan laws Gaius Sempronius Gracchus Born 154 BCE, nine years after his brother. Gaius’ politics were designed to benefit the common people, who he believed should have more rights Gaius’ political career started with a seat on the commission that oversaw Tiberius’ land reforms, though he quickly rose through use of his famed oratory skill, which were considered to be the best in Rome at the time. He quickly became at odds with the Senate, who feared the rise of another Gracchus. The Corn Law In an attempt to calm the poor, Gaius introduced his ‘corn law’, which allowed for Roman citizens to purchase grain from public storehouses for a set price below cost. As an attempt to calm the populace, it was a failure, though was popular enough that it was one of the last vestiges of the Gracchi reign, years after they’d died. It was, however, extremely expensive for the government; only a few years after the laws were instituted 320,000 citizens were being fed by the public grain. This was an early form of welfare. Judicial reforms Control over the courts dealing with extortion was moved from the Senate to the equites, which prevented acquittals based on nepotism, moved the support of the equites from the Senate to Gaius, and lessened the power of the Senate. If the People were to depose a magistrate he would be unable to hold magisterial office again. The People were able to prosecute a magistrate for exiling a citizen without trial. This law directly attacked a special tribunal with the powers of capital punishment which had been set up by the Senate to deal with Gracchan supporters in the aftermath of Tiberius’ downfall. Lex Militaris Shortened military service terms Established the age of conscription at 17 Required the army to provide equipment and clothing for the soldiers without deducting the cost from the soldiers’ pay. Senatorial Relations Relations between the Senate and Gaius had always been antagonistic, though as his popularity rose they became even less favourable. Gaius completely changed even the act of giving a speech, such was his influence. Previously orators speaking in the Forum would face the Senate house and Curia when giving speaking. Gaius, however, spoke facing towards the Forum proper, literally turning his back on the Senate. Popularity In 122 BCE Gaius was elected tribune despite having not campaigned or even put his name forward; he was elected through the sheer will of the people. The Senate responded to Gaius’ overwhelming popularity with populist measures designed to win back support as well as becoming more active in attempting to damage Gaius’ reputation. The Fall of Gaius Several events conspired against Gaius and he and his supporters were implicated in several deaths. Gaius also failed to win reelection as tribune for a third time, possibly due to vote tampering as retribution for removing the seats for gladiatorial shows so that the poor could watch. The Death of Gaius In 121 BCE Gaius and 3,000 of his supporters were slain by a group lead by consul Lucius Opimius. After Senate-incited bloodshed broke out, Gaius, refusing to take part in the bloodshed, fled to the Temple of Diana with the intention to commit suicide, though he was stopped by his friends. Gaius despaired after, upon the announcement of amnesty, many switched sides. After fleeing across a bridge, his pleas for assistance unheeded by onlookers, Gaius committed suicide the Head of Gaius The Senate issued the proclamation that whoever brought back Gaius’ head would be paid its weight in gold. The head was brought forward by a man named Septimuleius, and weighed at 17 2/3 lb., though it was discovered that Septimuleius achieved this by removing the brain and filling the cranium with lead. Because of his fraud Septimuleius was not rewarded. Aftermath The Senate’s handling of the death of the Gracchans was considered by most to be incredibly distasteful. The widows were forbidden to mourn their husbands and Gaius’ wife had her dowry confiscated, as well the families’ properties were confiscated by the state and sold and their homes were looted. The bodies of Gaius and his 3,000 supporters were thrown into the Tiber River rather then being given a proper burial. The son of one of the Gracchan supporters, who had acted as a messenger during the conflict, was executed, though by some reports he was allowed to choose his method of execution. Aftermath In celebration of their victory, Lucius Opimius, with the permission of the Senate, erected a temple to Concord, goddess of discourse, though the People felt that celebrating the deaths of so many citizens was distasteful. During the night the words ‘This temple of Concord is the work of mad Discord.’ were carved into the side of the temple. Legacy Within 15 years of Gaius’ death the reforms that the Gracchi had carried out were reversed or ignored and the situation of the poor became just as desperate or even more so then before. The Gracchi are considered to be one of the primary creators for the schools of thought that would become communism and socialism. Bibliography Author unkown, “TIBERIUS GRACCHUS (c.168 -133 BC) & GAIUS GRACCHUS (c.159 -121 BC).” The Romans. <http://www.the-romans.co.uk/gracchi.htm> Author unkown, “Gaius Gracchus.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. 5 December 2005. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaius_Gracchus#cite_ref-30> 8 April 2014 Author unkown, “Tiberius Gracchus.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. 14 May 2005. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tiberius_Gracchus> 14 April 2014 Morey, William C. Outlines of Roman History. New York: American Book Company, 1901. Appian (Trans. White, Horace). The Roman History: The Civil Wars, Book I. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1912 Shipley, Graham, et al, ed. The Cambridge Dictionary of Classical Civilization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006