Chapter 46 Summary Eisenhower had a good deal of experience

advertisement

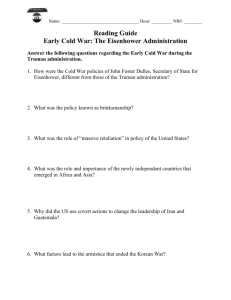

Chapter 46 Summary Eisenhower had a good deal of experience commanding, and he knew that he bore the responsibility for what acts he approved. He was comfortable with post-New Deal America, as were most of the wealthy Republican businessmen who had sponsored his political career. Eisenhower called his political philosophy “dynamic conservatism”--an attempt at balance between conservative and liberal philosophies. Eisenhower was no war monger. His ambition as president was to be remembered as a man of peace. Eisenhower made his biggest spending cuts in the military sector. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles's lack of the diplomat’s touch made him unpopular not only in neutral countries, but also with America’s allies. Dulles also saw communism as a monolithic force bent on conquering the world. He ignored evidence that he might be mistaken. A crisis in Iran provided him his first opportunity to overthrow what he defined as a hostile regime. Dulles also intervened in Guatemala when United Fruit was faced with losing its land. Also in 1954, Dulles refused to sign the Geneva Accords, which planted the seeds of the Vietnam War. Dulles espoused brinkmanship--"the ability to get to the verge without getting into war"--which got the United States into a few embarrassing situations in 1956. While Dulles rattled his saber, Eisenhower cautiously responded to peaceful overtures by Nikita Khrushchev. Acknowledging that nuclear war was unthinkable, the Soviet premier called for the “peaceful coexistence” of Communism and the West. Eisenhower sent Vice President Richard Nixon on a “goodwill tour” of Russia and agreed with Khrushchev to exchange visits. Due to the U-2 Incident, however, the Cold War was quite chilly again by 1960. After a brilliantly engineered campaign, John F. Kennedy narrowly won the Democratic nomination on the first ballot. The Republican nominee, Vice President Richard Nixon, had to defend the Eisenhower administration. Nixon was only five years older than Kennedy, but he never did overcome the popular perception that he was the candidate of the old order. Kennedy won by a waferthin margin. Kennedy was a masterful actor. There were plenty of Kennedy-haters, but in the glow of “Camelot,” they sounded sour and carping. Kennedy’s foreign policy advisors revived and updated containment policy with their doctrine of “flexible response.” The United States would respond to Soviet and Chinese actions not with Dulles’s bluster but in proportion to their seriousness. He preferred to back democratic reform movements in the “developing countries.” “Flexible Response” proved to be a disaster in Cuba. Kennedy’s Bay of Pigs fiasco heartened Nikita Khrushchev to take a harder line with the United States. In October 1962, the Cuban Missile Crisis brought the United States and Soviet Union to the edge of war, but a compromise averted catastrophe. Kennedy's assassination in 1963 was a national tragedy like Lincoln’s murder. Kennedy had inspired an idealism that, after his death, was to dissipate into disillusionment, cynicism, and mindless political and social turmoil.