The U.S. Supreme Court: Behind the Velvet Curtain

advertisement

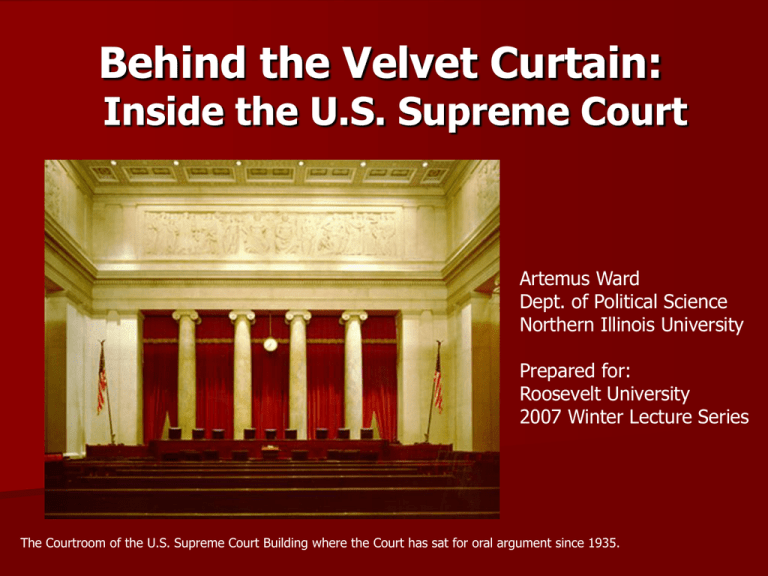

Behind the Velvet Curtain: Inside the U.S. Supreme Court Artemus Ward Dept. of Political Science Northern Illinois University Prepared for: Roosevelt University 2007 Winter Lecture Series The Courtroom of the U.S. Supreme Court Building where the Court has sat for oral argument since 1935. The Court is Shrouded in Secrecy We will discuss how a case moves through the Court with particular attention to: – The role of law clerks – The strategy, negotiation, and compromise among the nine justices at each stage of the process We will conclude by asking whether a Court composed of unelected, unaccountable, elite lawyers is good for America. “The Nine Old Men (and Women)” Research shows that the nine justices are generally divided along ideological lines: – 4 Conservatives: Roberts, Scalia, Thomas, Alito – 4 Moderate Liberals: Stevens, Souter, Ginsburg, Breyer – 1 “Swing Vote”: moderate conservative Anthony Kennedy Sorcerers’ Apprentices: Law Clerks Each justice has 4 clerks, the Chief 5, and retired justices 1 Recent Law School graduates largely from: Harvard, Yale, Chicago, Columbia, Stanford, Virginia, Michigan One-year clerking experience on the U.S. Courts of Appeals One year on the Supreme Court. After clerkship they can choose any job they want. Stanford Law School Supreme Court Law Clerks for the 2004-2005 Term (left to right): • • • • Clerk Aimee Athena Feinberg Roberto J. Gonzalez Kathryn Rose Haun Joshua A. Klein Grad Justice '02 '03 '00 '02 Breyer Stevens Kennedy O'Connor Deciding to Decide Discretion - the Court largely chooses which cases (petitions for write of certiorari) it wants to consider. Of the nearly 10,000 cases appealed to the Supremes every year, only 70 or so are decided with full written opinions after oral argument. How can nine justices examine nearly 200 petitions each week? Granting Certiorari Cert Pool - Cert petitions are divided up between every law clerk at the Court (except Justice Stevens’ clerks who work alone). The clerks prepare a brief memo on each case for all the Justices to read. Excluding the Stevens clerks, there are 34 clerks in the pool. Therefore, each pool clerk reviews and writes a memo on roughly six cases each week. Justice Stevens does not require his clerks to write memos on all of the petitions because if they did, each of his 4 clerks would be writing nearly 50 memos each week! Chicago Law School Supreme Court Law Clerks for the 2004-2005 Term (left to right): Clerk Grad Justice • Jeff Wall ’03 Thomas • Jay Richardson ’03 Rehnquist • Curtis Gannon ’98 Scalia • Jake Phillips ’03 Scalia • Dan Powell ’03 Stevens • Andy Baak ’03 Kennedy •Martha Pacold ’02 Thomas Granting Certiorari In the above pool memo, the clerk notes a circuit split and recommends grant. Cues - shortcuts that allow clerks and justices to determine cases “worthy” of consideration: U.S. government is a party to the dispute. Conflict among courts. Conflicting ideology between Supreme Court and lower court(s). Interest group participation. When 2 or more cues exist in the same case, chances of obtaining cert are high. Granting Certiorari A Blackmun clerk marks up the pool memo to note that it is from “Margo” Schlanger, a Ginsburg clerk who attended Yale Law School. Some justices have their clerks “mark up” the pool memo with their own views and recommendations. Justice Blackmun was suspicious of ideological bias and asked his clerks to mark up the pool memo with the information about the pool clerk who drafted the memo: the clerk’s first name, the justice they currently clerk for, the lower court judge they last clerked for, and the law school attended. Granting Certiorari Discuss List - The Chief Justice with his clerks makes up a list of cases he thinks ought to be discussed by the full Court. The other justices may add cases to the “discuss list.” Here, former C.J. Rehnquist [WHR] lists cases for discussion. Cases not listed by any justice are automatically denied. Granting Certiorari Rule of Four – by tradition, cert is granted if at least 4 of the Justices decide a case deserves to be reviewed. Here, Rehnquist and O’Connor vote that they will “join 3” meaning that if three others want to hear the case, they will also agree to hear it. Oral Argument Clerks prepare lengthy “bench memos” for their justices outlining the facts, issues, and possible questions to ask attorneys. During oral argument, justices constantly interject with questions. Research shows that oral argument matters. Quality arguments are more likely to win than poor arguments. Justices often foreshadow their position on the case through their questions and comments. Justice Blackmun’s oral argument notes provide a grade for each attorney. SG Wallace gets a “6” on a 10-point scale while his opponent, a “young” “36”-year-old from “UCLA” Law School scores a “5” Conference Vote In Conference the justices meet alone to discuss the cases they have just heard oral argument in. The Chief begins by stating the facts of the case and stating his vote. Votes proceed in order of seniority with the most junior justice speaking and voting last. The justices keep track of the voting and discussion. Here, Justice Blackmun notes that Justice Souter said he was “troubled,” “close to” the position of “J[ohn] P[aul] S[tevens],” and not with “N[ino] & K[ennedy].” Opinion Assignment Above: C.J. Rehnquist’s Assignment Sheet shows that J. Stevens assigned one opinion to J. Ginsburg while J. Blackmun assigned one to himself and one to J. Stevens. A day or two after conference, opinions are assigned by the Chief Justice if he was in the majority. If he wasn’t, the opinion is assigned by the most senior justice in the majority. Who writes the opinion is important because if 5 or more justices agree, the majority opinion is the law of the land. Opinion Assignment Strategy The Chief is concerned with distributing the workload evenly. Chiefs often assign important, groundbreaking cases to themselves. In closely divided cases, opinions are assigned to justices who are on the fringe or are unsure of their position if their vote will constitute a majority swing votes. Some justices become expert in a particular area and get the opinion assignment in those cases. When Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Stevens disagree, Stevens controls the opinion assignment. Opinion Writing The justice who the opinion is assigned to directs his/her law clerk to write the first draft of the opinion. When the justice is satisfied with the result, it is circulated to the other justices. At right are Justice Blackmun’s hand-written corrections to his clerkwritten draft of a death penalty case where Blackmun decided, “I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of death.” Coalition Formation: The Clerk Network Chief Justice Rehnquist with his Law Clerks. 2002. After the majority opinion author circulates a draft, the clerks from the other chambers review it and if necessary suggest changes and make recommendations to their justices. Memos are then sent to the opinion author. The clerk who originally drafted the opinion reviews them and makes recommendations to the justice about what should or should not be changed and why. Clerks mine the “clerk network” during lunch-time, in the hallways, and on the basketball court—the highest court of the land—to find out information for their justice on the positions of the other justices. Coalition Formation: Separate Opinions Justices who are only partially satisfied with the reasoning of the opinion, but agree with the result may issue their own concurring opinions. Justices who disagree with the majority may write dissenting opinions. At left is one of J. Blackmun’s circulation (log) sheets. He used these to keep track of the memos and separate opinions circulated in each case. Conclusion Americans trust the Court far more than congress or the presidency. Some of the most controversial issues in America have been decided by 5-4 votes on the Supreme Court: a presidential election, affirmative action, school prayer, abortion, etc. Justices have life tenure. No justice has ever been impeached and removed from office. Average life expectancy of justices is 87—ten years longer than U.S. average. Should we make changes in judicial tenure or in the way the Court J. Stevens was born on April 20, 1920 operates?