DARE students and the FYE 2012 final

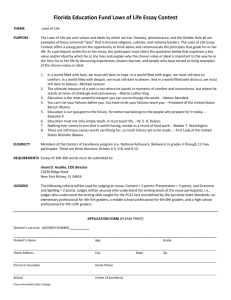

advertisement

DARE Students and the First Year Experience 2012 Alison Doyle Disability Service Trinity College Dublin June 2012 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 METHODOLOGY 6 Research Design 6 Sample population 8 Ethical Considerations 8 Research Method 9 FINDINGS 10 Survey results 10 Interview results 22 CONCLUSION APPENDICES 24 Error! Bookmark not defined. ABSTRACT The objective of this mixed methods study was to examine the first year experience of students who accepted a college place on reduced points under the DARE scheme (n = 74). Quantitative data from a survey examined ease of transition from school to college, the registration and orientation process, quality of human support provided pre and post-transition, access to disability supports, and experience of the DARE process. Qualitative data from interview transcripts explored knowledge of College structure and organization, pre-registration / pre-entry initiatives, registration and orientation, connecting with other students, provision of advice and support, campus ethos and environment, level of academic ‘readiness’ and skills, diversity and inclusiveness of college population, and the overall First Year Experience. Key findings indicate that 50% of students found registration problematic / confusing, and 90% did not have the appropriate academic skills required for third level study, 12% felt that this was not provided to them by College. 77% of students have a clear understanding of College structures and procedures, Most students indicated ease of transition was related to appropriate course choices, and 60% identified a positive message of ‘can do’ that made a distinct difference to success and engagement. 20% of students reportedly were unaware of who to contact for assistance or where to locate helpful information. Overall students indicated that the transition process was a positive experience, with 99.9% of students stating that College is an open, inclusive and welcoming place. Results suggest that future pre-entry work should focus on providing accurate and indepth knowledge about college systems and structures, and course specific information that permits students to make more appropriate choices. Critically, academic and study skills need to be embedded within programmes in the first semester, in order to bridge the skills gap. The process of student / institutional engagement has to begin at pre-entry, prior to the orientation period. INTRODUCTION The First Year Experience has been the focus of research for the past twenty years, principally in the US, Australia and the UK. The first year of college or university is observed to be central to student retention, and identifying effective ways of assimilating new students is a conundrum that exercises institutions annually. Tinto in particular (1997, 2000) makes a clear statement about the necessity to ‘consider ways to change our institutions to better fit our students, rather than change the student to fit the institution’ (Nutt & Calderon, 2009, p. 4). However this is not simple to achieve in practice. HEIs have flirted with a range of initiatives such as summer camps, shadowing days, orientation programmes, open days, information packs and websites, with varying degrees of success. In the Republic of Ireland, students study for the Leaving Certificate examination, an extremely competitive points-based examination taken at the end of the senior cycle of education in which students must present a minimum of five subjects, and which must include Mathematics, English and Irish, the latter including aural, oral and written assessment. In practice students usually study seven subjects and points are achieved on their best six results. Thus there are significant educational targets that must be achieved in order to qualify for post-secondary opportunities, which may also constitute an additional hurdle for disabled students who have experienced disadvantage during their school career. Such disadvantage is recognized by the Disability Access Route to Education (DARE), a third level admissions scheme for secondary school students who have the ability to benefit from and succeed in HE, but who may not be able to meet the points for a third level course due to the impact of their disability. Fourteen HEIs currently participate in the scheme which identifies Leaving Certificate students who are eligible to compete for an offer of a college place on reduced points. All HEIS participating in the DARE scheme have a responsibility to ensure that DARE students are provided with the supports they need to successfully transition into college, and to remember their first year experiences as a positive stage in their life. METHODOLOGY The objective of this study was to examine the first year experience of students who accepted a college place on reduced points under the DARE scheme. The principal aims of the research were: 1. To examine practical and personal variables involved in the process of transitioning from school to college; 2. To compare experiences of support in school to experiences of support and assistance in college; 3. To acquire a detailed view of the first year experience for students with disabilities; 4. To identify areas for improvement and factors that will inform pre-entry activities in the future. Research Design This study uses an emancipatory approach which provides students with an opportunity to voice their experiences of reasonable accommodations as they relate to formal examinations. A mixed methods approach was adopted, enabling a clearer understanding of the data collected in relation to the research questions (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2007), using a concurrent-convergent design with triangulated data collection (Creswell, 2003). Quantitative and qualitative data were gathered via an online survey and in-depth interviews. The survey was designed to capture quantitative data about ease of transition from school to college, registration and orientation process, quality of human support provided pre and post-transition, access to disability supports, and experience of the DARE process. Qualitative data was collected by providing an opportunity to submit free responses in comment boxes for each question. Semi-structured interview questions were themed into the following strands: College structure and organization, pre-registration / pre-entry initiatives, registration and orientation, connecting with other students, provision of advice and support, campus ethos and environment, level of academic ‘readiness’ and skills, assistance with the transition process, diversity and inclusiveness of college population, and the overall First Year Experience. Responses were collated under each theme and a content analysis conducted to identify codes to be used as the basis for quantitative analysis of the text corpus. An inductive coding approach was used with each narrative segment permitted to have several codes attached. Sample population The purposive sample population was identified as TCD entrants who had applied for entry to College via the DARE scheme, and who were approaching the conclusion of their first year in college (n74). Whilst there was an assumed probability that this population would also include all disabilities, the actual distribution is illustrated in Figure 1. 25 22 20 15 15 12 10 5 6 5 3 5 2 4 0 Figure 1 Profile of purposive sample Ethical Considerations An explanation of the purpose of the study was provided in the email invitation and also on the first page of the Internet survey. Participants were assured that data collected would be anonymised. They were not asked to submit any identifying data. For the interview process participants were randomly allocated to interviewers within DS with whom they had no service relationship. Students who did not attend their appointment were subsequently contacted by telephone to re-arrange an interview time. Where students did not attend the second appointment, they were not contacted again. Non-attendance was considered to be an indication that students did not wish to engage. It was felt that pursuing participants at this point would be indicative of coercion and thus unethical. Interview notes were anonymised and labelled by interviewer initials and interview number, for example AD2. Data was stored in a password protected folder within the DS intranet. Research Method This research study uses a mixed methodology. The intent was to add depth to quantitative results using qualitative data (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2007). No priority was given to either quantitative (QUAN) or qualitative (QUAL) data collection or analyses, both were integrated into the research process from the beginning and were collated and analysed concurrently. The findings of both data sets were converged during the interpretation phase, and integrated into the discussion. Quantitative and qualitative data was collected via 1) survey, and 2) semi-structured interviews. The survey was designed in Surveymonkey and pilot questionnaires were distributed to students and staff and subsequently revised on the basis of feedback. Similarly semi-structured interview questions were identified, discussed and subsequently modified. Students were sent an email on 6th March 2012 which asked them to indicate a convenient date and time for interview within a two week period (26th March 2012 to 6th April 2012). After a lapse of one week non-respondents were contacted by telephone and invited to make an appointment. Students were randomly allocated to one of nine interviewers working within DS with whom they had had no previous contact. Interviewers were provided with an interview process guide and a copy of the semi-structured questions. Interviews lasted between 20 – 30 minutes and took place in the interviewer’s office. These locations were private and did not permit identification of any of the participants. FINDINGS Response rates were as follows: survey n = 30 (40.5%), interviews n = 40 (54%). Full and complete quantitative and qualitative results are available. Survey results A profile of survey respondents is provided in Figure 2. The SpLD group accounted for the highest number of respondents (n = 12) which was not unexpected as they represented 30% of the target population. Whilst there was an 80% response rate for the ASD (n = 5) and ADHD (n = 4) groups, only 13% (n = 15) of students with SOI responded. Of note is that none of the students with sensory disabilities (Blind / VI, Deaf / HI) elected to complete the survey. Figure 2 Profile of student respondents Students were asked to rate their transition experience (Figure 3), with 80% indicating a positive transition to college ranging from Manageable to Very Easy. However 20% state they found the process very difficult, which is an unacceptably high rate, and 19 students submitted comments on the reason for the quality of their experience. An analysis of which indicates that positive experiences were a function of timely and effective pre-entry information / programmes, supports from College staff and services, and course choice. Figure 3. Experience of transition from second to third level “I think it was due to the course I got as I enjoyed going into college every day and learning something new on that subject. Also everyone was very helpful around college with any small problems I had and I met nice friends which also contributed to a fairly easy transition from second level to college for me.” Negative experiences were attributed to distinct differences between second and third level structures and academic expectations, and the degree of freedom and independence expected of students. “High level of freedom in relation to attendance etc made it difficult for me to be strict with myself about punctuality. The scale of the difference between school and college life caused a surge in new compulsions for me (OCD).” Registering with DS and, perhaps surprisingly, organising accommodation were not areas of concern. However there was a particular difficulty with technical processes. Registering on their course, obtaining a student card and activating email were all areas described as confusing, complicated or problematic, “Signing up for Webct and my Myzone account was very tedious”. “Registration was problematic as the college had lost results of my Pre reg blood tests and my registration was delayed”. “Dealing with student records and IS Services which was drawn out and caused un-needed stress.” College friends or knowing someone in college, parents and family and Disability Service supports were identified as making the transition to college easier (Figure 4). Only one respondent mentioned a teacher, no other school-related support was stated. Students indicated that these individuals or providing information, explaining options and assisting with decisions were major factors in ease of transition, as were discussing and advising on disability-related supports (53.3%), and having an understanding of the student’s disability (46.7%). Significantly, 60% of students stated that being provided with encouragement was an important feature of the transition process. “It was nice that there was someone there who understood that things weren't easy for me and that I was struggling at times. At one time in particular during the college year I was having a particularly hard time but Unlink was there for me and helped me through it.” Figue 4. Human support in the transition expereince Which of these people made transition to college easier? You can choose more than one answer. Answer Options Response Response Percent Count Unilink Service 26.7% 8 Parents 53.3% 16 Family support 30.0% 9 College friends 56.7% 17 School friends 20.0% 6 Knowing someone in 40.0% 12 College Tutor 26.7% 8 Disability Service 36.7% 11 College Lecturers 23.3% 7 Nobody 3.3% 1 college The next two questions compared levels of support experienced in college and in school (Figure 5). Levels of satisfaction with support in college were high with 76% of students stating they were well supported, 83% know where to go and whom to contact to source help, 80% of students felt that they had been provided with the opportunity to discuss problems, and 67% have a key person that they can reply on for support and guidance. It is of concern that approximately 20% of students did not know where to source help or whether they had a key person to support them. Seven students submitted additional comments, three of whom identified the Unilink Service as being of significant benefit, and one student described their college tutor as being ‘wonderful’. Figure 5. Quality of support provided in College Two comments stated that the differences in support style and availability to be challenging: “I just find it weird how it’s not like school where if you’re stressed you go up to a teacher and they advise you but if you want advice it seems like such a process like emailing them, having to meet them.” “It took me a while to work out who to go to, and what I needed to ask for. For example, it wasn't till the 2nd term that I linked in the academic support.” Students were then asked to describe the quality of support in college compared to their experience of support at school (Figure 6). Figure 6. Level of support in college compared to level of support experienced in school Results indicated an overall improvement in areas of: understanding of needs (60%), increase in available support (63%), ease of locating supports (50%), increased professionalism (63%), helpfulness of staff (53%), better and more practical advice (60%), and ease of sourcing information (46%). Although only a small number of students identified these factors as being worse than their school experience, understanding of needs (20%) and ease of locating supports (20%) and sourcing information (23%), were identified as being particularly poor. The final question in the support section asked students to indicate their engagement with a range of technological and academic supports available through DS (Table 1). Frequently Often Sometimes Rarely Never 2 4 1 4 20 5 6 2 4 14 Learning support 1 4 7 4 16 Skills4Study Campus 0 1 6 4 20 Photocopy cards 7 3 5 3 13 Unilink 4 2 5 4 15 Extended library borrowing 4 2 3 4 18 Assistive Technology (Texthelp / Dictaphone etc.) Disability Service (ATIC) room in libraries Table 1 Engagement with academic supports For the purposes of this analysis, results for ‘Never’ and ‘Do not use’ options were combined. Although 60% of students indicated that they never used Assistive Technology, 53% did not use learning support and 50% did not use Unilink, these are idiosyncratic supports so should not be considered as an area for development. However 47% also stated that they never used the ATIC room, 60% did not use special library borrowing, 43% did not use photocopy cards, and 67% had not used Skills4Study Campus, which may indicate a lack of awareness of these supports. Three students submitted comments: “I wasn't aware of the extended library borrowing.” “I haven't engaged in any of these services because i just haven’t had time and the study skills weren't at a convenient time for me and I haven't used the extended library borrowing as I have some text books at home and the books were already checked out.” “I don’t like using the internet as I get carried away with it and go on social networks.” Students were asked to reflect on the usefulness of targeted transition initiatives for disabled students that could be included in Transition Year (TY). Results indicate that potential strategies were in general viewed positively. Figure 7. Transition initiatives for inclusion in the TY programme College application workshops, advice clinics and disability specific information were considered to be essential / useful by 73% of students, as were visits to disability services in colleges (66%), a transition website (63%) and curriculum time dedicated to transition planning (63%). With respect to overall experience of the DARE process, (77%) of students stated this was a positive experience (27% Very Easy, 50% Simple Enough). However the remaining 23% students described it as confusing, which is concerning given the transparency of the scheme, the levels of publicity, and availability of online and print materials. Figure 8. Student perceptions of the DARE process Two students left comments about this confusion: “It was confusing but when it was explained to me it became simple to understand”, and “I started panicking when filling in the forms that I might have missed something.” This would support the idea that students need a transition ‘partner’, be that a parent, carer, teacher, Guidance Counsellor or other stakeholder. Finally students were invited to submit advice about transitioning to college to future disabled students completing the Leaving Certificate. The full transcript is available in the Appendices. Of particular note is the general tone of the comments submitted by 29 students which was positive and enthusiastic. Statements were coded into themes and ranked by frequency as: importance of course choice (57%), asking for help (47%), applying to DARE (40%), participating in college social life (30%), using Disability Service supports (23%), the importance of developing independence skills such as selfdetermination and self-awareness (15%), course preferences (6%), and future career and opportunities (3%). Students were emphatic about the importance of selecting not just the right course, but one that would be of sustainable interest and play to the strengths of the student: “In relation to course choice you really should research the course of your interest before you commit to it on the CAO. I personally wrote down law on the basis that I had spent my work experience in transition year in a solicitors office however I didn't have a true insight into the course and I was basing my opinion of law on the work of solicitor and this didn't give me a true picture of the level of work that has to be put into the actual course. As a result when I started my course I was overwhelmed by the level of work that was expected of me.” “A few of my friends who believed that they were suitable candidates did not in fact end up with a DARE allowance and therefore were not served well by their CAO choices. Choose a course that you know you will enjoy and that you feel suits you, therefore you will be happy and willing to work hard at whatever difficulties may arise for you in your chosen course.” Of critical relevance to this process is the quality of guidance and advice that a student receives: “Personally my career guidance teacher was very unhelpful she didn't want to assist me and she made this very clear when she kept telling me that I was no different from anyone else and that everyone finds the Leaving Cert difficult. She was of the opinion that I shouldn't be allowed access to the college via the DARE system and did everything in her power to make it sound as if I didn't need help in the letter that she was asked to send to DARE re my application.” Students were encouraging about the need to ask for help and specifically that students should act as self-advocates and actively seek help for themselves: “Students must always remember that help is always given to those that seek it.” “Help in college: All you have to do is ask, whether it is your assigned OT person or lecturer or tutor and they will help you as much as they can.” The value of applying to DARE was a feature of many comments, although one or two students stated that they had not been made aware of the scheme by their school. One interesting comments reflects a negative experience of disclosure with respect to DARE: “Apply to the application form, keep it confidential, there is a lot of resentment from other students.” A point that was mentioned several times was the importance of the personal statement to the application: “Do not hold back in describing all of the things holding you back in your studies as all of these difficulties can be helped through the various support systems put in place in TCD.” Interview results Organization: Do you understand how college is organized so that you know where to go if you have an administrative or academic question? Figure 9. Knowledge of College organisation and structure The vast majority of students (77%) had a clear understanding of how College operates and is structured into academic and administrative areas. All of the respondents who indicated that they found these aspects initially problematic or confusing, stated that they relied on fellow students to assist with tasks such as timetabling, registration, the library, webct and locating venues. Students stated that they would ask an academic, tutor or DS personnel if they required assistance. Pre-registration: What kind of activities or programmes would help with the transition process before registering in college? Figure 10. Student suggestions for pre-entry activities 30% of students were not aware of anything in particular that needed to be improved, compared to 65% who provided suggestions for improved activities. Academic resources included prior knowledge of book lists, online materials and more subject specific preparatory classes, for example Anatomy. Better pre-entry and orientation activities were identified as course specific tours that included visiting venues, and more course specific requirements in advance of registration: "While I chose the right course for me, there is a lot I would have liked to know about it in advance. For example, it would have been great to get key readings in advance so I could have started on the readings the summer before I began. I did not know that my Irish Sign Language classes would be conducted completely through ISL and that is huge. It would have been useful if I had been able to begin studying ISL over the summer in preparation." “Was not clear who to go to in the school with any particular issues. A specifically and clearly identified person in the department would have been very useful. Tutor was very good but was not based in the department. Friends reported that tutors in the department were very useful.” Registration & Orientation: how would you describe your experience of the early days of your transition into college? There was an even distribution of positive experiences (50%) contrasted with students who found the process confusing and problematic (50%). Positive feedback highlighted the importance of making friendships, joining societies and settling in to a routine quickly. Negative experiences included not being assigned a tutor from the beginning, studying within a large cohort with multiple subject choices / strands, and living away from home. The processes involved in the registration process caused particular problems: "The registration process was really tough. I had to queue for one and a half hours when then when I got to the top there was a fee query so I was sent away to sort it out. I only sorted wifi out last week (April 2012). It was quite difficult to set up and it was intimidating seeking out someone who could help.” Connections: As a new student, to what degree has this college connected you with other new students / academic supports? The purpose of this question was to establish student opinions on College’s efforts to connect students with one another, and to academic resources. Overall 85% of students feel linked in with both peers and college structures as a result of support from the Disability Service, academic staff and students, and many comments praised the Student 2 Student service. Connections with other students / supports 29 5 Good: I felt connected Adequate 7 3 Disappointing / problematic Not College's responsibility Figure 11. Student perceptions of links within college “The college really made an effort to connect with me. All of my lecturers are very approachable and you wouldn’t feel intimidated asking them a question in a one on one situation, it can be more difficult in a lecture but afterwards is fine and they generally are great help.” “I found that the college really made an effort to connect with me. Especially through the Students’ Union. I think that I would feel most comfortable going to them if I had a problem.” “I think that small seminar classes were a good place to make friends, some of my now best friends I met in seminar classes. I think generally I’m more inclined to go to something if it’s in Trinity and with Trinity people if its geared towards socialising. I didn’t really use the academic supports like “Skills for Study” but the effort was definitely made to link me in with supports.” However 17.5% of stated that this aspect of their first year experience had been disappointing or problematic. Helpfulness of academic staff was variable depending on course / subject, and ‘connectedness’ was very dependent upon the size of the course with larger lectures being quite alienating, and understanding and using College communication systems was crucial: "I think students should know that setting up a connection with the internet is very important. I didn’t realise email was so important. It should be communicated more that email is the primary way in which college will contact you. Sometimes my lecturers email three hours prior to a lecture to cancel.” Advice: To what degree have admin / academic / services staff explained the requirements for your course, or helped you manage your course? Understanding the content and requirements of a course, together with having appropriate academic skills, was one of the most frequently cited concerns of students throughout all of the interviews and survey comments. Statements were split between a straightforward, good or ‘as expected’ experience (72.5%), contrasted with service that was not helpful, vague or requires improvement (27.5%). Positive comments related to solid information provided in Fresher’s week, introductory lectures, accurate and detailed course handbooks, and helpful administrative and academic staff. Criticisms included detail such as weighting of exams not explained very well, and in some cases information in the handbook changed during the year. In one case the student felt that the title and course description was misleading (Business and Computing). “This is something that I found particularly difficult I did not do enough research into my course maybe but the weighting of the course seems to be more on the computer science end and I was expecting more of a focus on Business…I thought that even the name of the course suggested that the main aspect was going to be business and I have struggled with Computer Science. Also we are in the same classes for maths as the computer science course and they all required honours maths and I didn’t do honours maths so I, like most of my class, get lost easily.” Campus environment: How effective is College at helping students feel safe, welcome and that their needs are met? 90% of students agreed that College made every effort to ensure that students felt welcomed, included and safe, however to a large extent this was very dependent upon the size of the course and the level of engagement with social activities. “It’s done a good job for me. It is helped by having a small course, only 30. I’ve made friends and I feel looked after by staff. We have tutorials in each subject with only 15 students so there’s a chance to get to know each other.” “TCD is pretty diverse. There are lots of mature and foreign students here and that gives a spice to College.” Criticisms were largely expressed by Nursing students who did not feel that they were part of the general campus, and this was exacerbated by time spent on placement. Skills: how well do you think you were prepared in terms of the academic skills required for your course? How well has college helped you to improve these skills? Responses to this question highlighted a significant skills gap between second level and third level requirements, with 90% of students indicating that they needed help with gaining or improving academic skills, which in general was made available to them. Figure 12. Level of academic skills required for third level For some students this support was provided early on, but others found it took time to acquire the right kind of skills quickly and efficiently. “I was prepared but only because I did the IB which has academic skills as part of it for example how to read and write research papers. I know people who came through the Irish system and didn’t know what a bibliography was. Being in and on the course has improved my skills but it is something I worked on by myself.” “There’s a gap between LC and College. College is more self-directed. It’s a stereotype but it’s true. In the LC you learn the book to prepare for the exam. In College you have to explore the library and you need to do your own analysis to get good grades. In maths we have weekly assignments which help prepare you for term tests and in philosophy and politics we’ve had tutorials on essay writing.” “My research skills before this course were non-existent as my school didn’t even have the internet and now that everything is at my fingertips I have had to get to grips with that quickly. You have to learn quickly what is relevant and not relevant as this is not always clear from the lectures. I have had to get better at filtering information that is not important. I wasn’t good at this at the start but am learning how to do this now.” Only two students felt they were academically ready for the challenge of third level, and a further five did not feel that they had a baseline of skills to build on, and lacked support to improve these skills. “The leaving cert is a joke. It doesn’t prepare you to think or be prepared for College. There is no critical thinking. International students are better educated compared to Irish students entering College.” "Needed to study right from the start, could not ease one’s way into the course. Methods of learning Anatomy could have been outlined from the start to make engagement with the subject easier. Developed the skills to do this after Christmas.” Transition & Support: what kind of support should College provide to help students manage first year? There was an equal distribution of opinions that very little more is required than already exists (50%), and the remaining 50% believed that only a small improvement in some areas would be required. Many students stated that no matter what support was put in place, the transition to third level is a big jump, but that online resources online and open days that are available to students, provide them with an opportunity to be aware of what to expect in the first year of college. Suggestions for areas of improvement included: Promotion of academic skills Books in accessible formats Feedback on expected academic standards and performance One stop student information desk Opportunities to engage with peers on very large classes Discipline specific peer mentors The most successful transitions were described where students had a broad engagement with all aspects of College supports whether they be technical or human. "I met my Disability Officer and she showed me past papers websites. I found this really helpful, and it was good to do it before college started. She emails me all the time and I email her back. I also met with the ATIC advisor and he gave me Read and Gold and I do typing with -TTRS, this has really helped me academically. I also joined Societies such as the Hist and the Phil and I go to their debates.” Diversity: how open is College to acknowledging and accepting a diverse student body (disability, background, culture)? An overwhelming majority of 96% of students are of the opinion that College is diverse, accepting, integrated and acknowledges difference and individuality, principally due to a sense of identity and community. Some students believe there is less of a distinction made between students from Dublin and outside of Dublin, how several students stated that externally “there are still some public perceptions that Trinity is stand offish,” and there appear to be particular issues with entrance via the DARE scheme: "Before coming in I was told not to tell people I came in on DARE, and in school it was a big secret that I got accommodations.” “I do think there is a huge stigma attached to the DARE scheme. I have had other students comment on how ridiculous it is that someone got in on reduced points. I have never told anyone I’ve got in on DARE, it would be viewed like I have a second class degree. I have had students with hundreds of points less than me comment in a negative way about the DARE scheme.” First Year Experience: what is your overall satisfaction with College: social aspects, your course, services? Would you recommend this college to anyone? A resounding 100% of students enjoyed their first year – despite initial difficulties settling in, and would recommend Trinity to prospective students. “Overall I’m very happy with college. Intellectually I feel stimulated and fulfilled. I have a lot to amuse myself with and I do feel that I have sufficient supports. I enjoy my college life more than secondary school. I’ve lost contact with a lot of my secondary school friends. College is a great place to develop my independence and skills.” "I love everything about Trinity, it’s great, I’ve always wanted to go here and all my family went here. I love my course, I always knew what I wanted to do, I have heard so many people say that they hate their course. I was aware to take it as it is. I really appreciate the options available through the course I’ve chosen as my degree. I’m very happy with the services available in college; I really don’t know what else you could do for me. I think it would be really hard to convince me to go anywhere other than Trinity even Harvard! If someone gave me one issue about Trinity I could probably name about 10 reasons why you should come here." CONCLUSION Findings from the survey that was administered to DARE students indicate a positive experience of the transition process. As 20% of students found the practicalities of beginning college life difficult, this indicates the need to pre-identify students who may find those tasks challenging, and to implement a mentoring or peer partnership scheme. The majority of students stated appropriate course choices as a reason for ease of transition, and this was also a major feature of their advice to future DARE students. Future pre-entry work must focus on providing accurate and in-depth knowledge about the way college operates as a system, and an interface for providing students with course specific information that meets the needs of a technologically savvy generation, who require a higher level of accessibility than is currently provided. College admissions schemes and student services need to engage all stakeholders working with disabled students: parents, carers, school staff and in particular Guidance Counsellors. It is clear that simply providing print or electronic materials is insufficient. An important point that should be considered by all HEIs is that whilst college staff are very familiar with practices and procedures, for each new cohort of potential students and parents, the process is new and unfamiliar. It is clear that the process of encouragement has to begin at an earlier stage than immediately before entry; 60% of students stated that it was the positive message of ‘can do’ that made a distinct difference to success and engagement, and this is very closely tied to the aspiration to transition to third level, including the various processes linked to that aspiration, including DARE application. Students indicated college application workshops, advice clinics, visits to / by disability services, a transition website and curriculum time dedicated to transition planning as being essential. Application clinics are already provided through the DARE scheme, and DS participates in events providing information to students and parents. There are logistical difficulties involved in providing these outreach initiatives to individual schools with only a very small number of disabled students. Pathways to Trinity is a transition website that was launched in April 2011 and, as mentioned above, as each new cohort of senior cycle students is effectively new to the experience, this may need to be publicized more widely on an ongoing basis. The most obvious solution, as mentioned by students, is dedicated transition planning time and programmes within the school curriculum. More than 70% of students surveyed were confident about accessing supports and understanding how to go about this and linking in with a key individual. Of concern are the 20% of students who reportedly had no idea who they could contact for assistance or where to locate helpful information, including an identifiable individual responsible for providing support. As DS conducts an individual needs assessment with each student at the point of registration – generally well before the beginning of lectures in late August / early September, the conclusion is that whilst students are provided with this guidance, the morass of information and different layers of registration processes means that this advice is not retained. Therefore a more phased approach to registration would seem to be more suitable and productive, including a pre-entry / orientation session for students and their parents, a short course or at least School introduction, college systems and structures, followed by a needs assessment that takes place after a few weeks of academic study. A welcome outcome was the recognition by students themselves for the need to be self-aware, self-determined and to develop self-advocacy skills. This is the underpinning philosophy of the DS strategic plan: the Student Journey. The overwhelming perception of College being an open, inclusive and welcoming place is very encouraging. However, anecdotally, it is only once students have entered College that this is apparent to them. For many prospective students Trinity is perceived as a place that may not be accessible, that they may not visit or wander around. REFERENCES Creswell, J. W. (2003) Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Los Angeles: London, SAGE. Creswell, J.W., Plano Clark, V.L., Gutman, M.L. & Handson, W.E. (2003) ‘Advanced Mixed Methods Research Designs’, in A. Tashakkori and C. Teddlie (eds) Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Creswell, J. W. & Plano Clark, V. L. (2007) Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Nutt, D. & Calderon, D. (2009) ‘The First-Year Experience: An International Perspective’. University of South Carolina / University of Teeside: National Resource Centre Tinto, V. (1997). ‘Classrooms as communities: Exploring the educational character of student persistence’. Journal of Higher Education, 68(6), 599-623. Tinto, V. (2000). Learning better together: The impact of learning communities on student success in higher education. Journal of Institutional Research, 9(1), 48-53.