document

advertisement

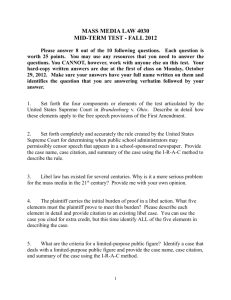

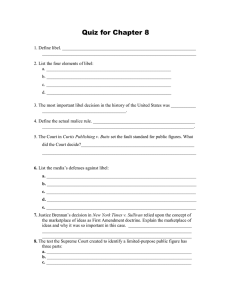

Chapter Four Objectives • • • • To define libel and slander To list the elements of libel To understand libel defenses To understand rules for public and private persons • To define anti-Slapp laws Libel awards rising! • 1996: average libel judgment = $2.8 million!! (that’s AVERAGE!) – Can put smaller publications out of business • Largest judgment to date: MMAR v. Wall Street Journal (1997): award of $222.7 million against WSJ for publication about brokerage firm that put them out of business – Award reduced and then eliminated when found that firm had withheld crucial evidence from WSJ Fear of self-censorship • Tobacco company whistleblower Jeffrey Wigand’s interview with Mike Wallace for 60 Minutes was not aired after it was initially made, due to fears that Brown & Williamson would sue CBS – Interview was later aired – Wallace: “We continue to go after the big ones because it’s the big ones that count” Libel and slander “ … a great deal of the law of defamation makes no sense. It contains anomalies and absurdities for which no legal writer ever has had a kind word…” William Prosser Handbook of the Law of Torts Libel definitions • Defamation: communication that tends to injure someone’s reputation • Libel: written defamation • Slander: spoken defamation – We will use “libel” regardless of the action • Negligence: journalistic malpractice; sloppiness and mistakes • Actual malice: worse; knowingly publishing falsehoods or acting with reckless disregard How is libel handled legally? • Civil tort actions, NOT criminal actions • Usually in state courts, but federal courts do get cases (diversity jurisdiction) and will use state laws to determine outcome • States vary in their libel laws, even though Supreme Court rulings have made libel actions more uniform Overview of libel elements: Plaintiffs must prove… • Defamation: statement must tend to hurt someone’s reputation • Identification: statement must somehow identify its intended victim • Publication: statement must be heard/seen by someone other than victim and source • Fault: at the appropriate level • Damages: losses that can be monetarily compensated Elements of libel: Defamation • • • • Defamation is a communication that damages the reputation of a person, but not necessarily the individual’s character Your character is what you are Your reputation is what people think you are. Reputation is what the law protects. Elements of libel: Defamation • Libel per se vs. libel per quod – Libel per se is when words “on their faces” are libelous: “crook,” “racist,” “murderer,” “adulterer,” “prostitute” • Falsely accuses someone of crime, immorality, infection by loathsome disease, incompetence – Libel per quod is when context is necessary to be defamatory • E.g., reporting that man is “steady dating” a woman when he is in fact married to someone else Identification: Who may sue? • Any living person or other private legal entity (like corporation): libel is a personal right not property right, so it dies when person does – Some states permit heirs to sue (NJ, PA) – Many states let heirs continue existing suit • Group libel: no individual may sue for libelous statement targeted at group – Cutoff? Between 5 and 100 – The larger the group, the less chance individuals have to be able to sue for libel Elements of libel: Identification • At least some readers/listeners must be able to identify who is being libeled • Use of name is obvious, but there are other ways – Title (president of university); address (1600 Pennsylvania Blvd.); description (lead actor in Indiana Jones movies); job (Attorney General of the U.S.); initials (JFK, LBJ) Elements of libel: Identification • If identification is vague or incomplete, other parties may sue – Behrendt v. Times Mirror Co. (CA App. 1939): Ralph A. Behrend and R. Allen Behrendt both worked at same hospital; LA Times reported Dr. Behrendt had been arrested for theft and narcotics—when actually it was Dr. Behrend who had, so Dr. Behrendt sued and won Elements of libel: Publication • Victim + source + one other party = publication – Fewer people hearing it = less damages suffered – Republishing libel, even accurately and with sources, does not exempt from liability – Everyone who disseminates can be liable • Single publication rule: initial publication is one libel, no matter how many people see it—no perpetual libel suits Elements of libel: Fault • 90% of all cases hang up here – Pre-Sullivan, fault assumed for plaintiff • Different kinds of people have different levels of fault to prove – Public officials and public people must prove actual malice: that media knew something was false and published it anyway, or acted with reckless disregard for truth (didn’t care) – Private people need only prove negligence: journalistic sloppiness • Much easier for private people to win libel suits! New York Times v. Sullivan, 1964 • Starts modern era of defamation • Introduces concept of requiring fault in libel actions • Adds element of actual malice (publishing with knowledge of falsity or reckless disregard of the truth) Changes from common law • In original common law of strict liability (SL), defendant had high burden of proof – Defendant had to show that it did not libel someone—hard to do – Plaintiff only showed defamation, publication and identification took place; media had to demonstrate that it had not libeled – Truth not a defense: “the greater the truth, the greater the libel” • After Sullivan (1964), libel considered as constitutional question, with 1A protection, and burden of proof shifted to plaintiff (MAJOR) Fallout from New York Times v. Sullivan, 1964 • Actual malice rule applied to public figures who held no office (Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts and Associated Press v. Walker) • Actual malice rule applied to private citizens involved in matters of “public interest” (Rosenbloom v. Metromedia, 1971) New York Times v. Sullivan, 1964 revisited • States could allow a lesser standard of proof (negligence not malice) for private persons (Gertz v. Welch, 1974) • Private persons thrust into the limelight do not have to prove actual malice (Time inc. V. Firestone, 1976) Elements of libel: Damages • Any plaintiff MUST prove some damages to win (no damages, no case) • Varies based on award sought and whether public or private plaintiff – Punitive damages require proof of actual malice, at all levels Defenses to libel: hard-line • Truth: absolute defense – Plaintiff must prove falsity—but if you can prove truth, you win—it’s hard! – Not a defense to print accurate account of what someone else falsely said (unless from a gov’t proceeding or document) • Privilege: three kinds – Absolute: rare for media – Conditional/Qualified: like private facts defense of public record/public proceeding: truthful coverage of gov’t proceedings or documents Falsity • Before 1964, falsity assumed, defendant had to show otherwise—now plaintiff must prove • Philadelphia Newspapers v. Hepps (1986): Maurice Hepps alleged by Inquirer to be linked to organized crime; he couldn’t prove falsity, but PI couldn’t prove truth – Hepps lost: Where speech of public importance is concerned, all plaintiffs, public or private, have burden of proving falsity (in favor of speech) • Truth an absolute defense—but very, very hard to prove to jury Privilege • Hutchinson v. Proxmire (1979): Sen. William Proxmire of WI issued “Golden Fleece” awards to people he thought wasted taxpayer money – Dr. Hutchinson studied teeth-clenching monkeys, sued for libel on Proxmire’s press release – Court said he wins: privilege does not cover press release, only Proxmire’s remarks on Senate floor recorded in Congressional Record (even if verbatim) • So this defense is limited Defenses to libel: hard-line • Fair comment and criticism: similar to opinion defense – Must be based on facts and not published with malice • Consent (of course!): but be careful—could be setup if someone permits publication of info defamatory of them • Statute of limitations: if libel action not filed within set period of time, statute “runs” and claim cannot proceed (1-2-3 years usually, varies by state) Fair comment and criticism • Milkovich v. Lorain Journal Co. (1990): HS wrestling coach sued newspaper that alleged he lied under oath about fight at wrestling match – Court said no constitutional privilege for opinion when based on false statements of fact, unsupported facts, or implied facts – To write “in my opinion, Jones is a liar” is no defense—charge implies knowledge of facts • Court affirmed Hepps in that plaintiff must prove falsity • If something can be proved, probably not protected: “X is bad” vs. “X did a bad thing” • Good protection for pure opinion, however Defenses to libel: mitigating • Correction/retraction: “I take it back!”—timely – Might satisfy plaintiff; usually prevents punitive damages • Libel-proof plaintiff: plaintiff’s reputation so bad already that couldn’t be further harmed • Neutral reportage: reporting all sides of controversial issue of public importance fairly (2CA opinion, few states recognize, not CA) • Right of reply: when one media sues another, first claims it was merely replying to attacks by second • Usually reliable source (a.k.a. wire-service defense): source was reliable in past Trade libel (a.k.a. “veggie libel”) • 13 states have “food disparagement laws” for growers/ranchers to help recover damages from anyone who alleges health risks associated with their product • Texas Beef Group v. Oprah Winfrey (Tex. 1998): discussion about mad-cow disease prompted Oprah to say, “It has just stopped me from eating another burger” – TX cattle owners sued, claiming beef prices dropped as result of her comment – TX court said couldn’t use TX food disparagement law Libel on the internet • Telecommunications Act of 1966 – Internet service providers are not to be treated as publishers – Thus, the are not liable for content of messages they carry – Thus, they can not be sued for libel – Providers free to screen materials they consider inappropriate SLAPP lawsuits • Strategic lawsuits against public participation – Legislation that says if a plaintiff files a merit less lawsuit to discourage the defendant, the defendant can require the plaintiff to pay attorney fees – Allows the court to dismiss frivolous lawsuits Conclusion • Defamation is an expression that damages a person’s reputation. Printed defamation and most broadcast defamation are considered to be libel. • Slander is spoke defamation. • Civil libel—whereby one person or organization sues another for monetary damages is most common. Conclusion • Libel elements include defamation, identification, publication, fault, damages. • Libel defenses include truth, privilege, fair comment and criticism, consent, statute of limitations. Conclusion • In New York Times v. Sullivan, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled for the first time that the First Amendment protects the publication of false statements that damage reputation. • Public officials suing the media for statements about their conduct must prove that defamation was published with knowing falsehood or reckless disregard for the truth.