Timeline - WordPress.com

advertisement

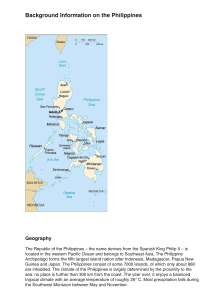

Timeline of the Filipino-American War And US Colonial Rule in the Philippines The Philippine-American War has been described as the United State’s first Vietnam War because of its brutality and severity. According to the PhilippineAmerican War Centennial Initiative (PAWCI), roughly 22,000 Philippine soldiers and half a million civilians were killed between 1899 and 1092 in Luzon and the Visayan Islands, while one hundred thousand Muslims were killed in Mindanao. The United States joined the ranks of colonial powers in Asia with support from American Expansionists and Protestant missionaries, but over the objections of domestic tobacco and sugar producers. Strategic interests proved most decisive in the age of Alfred Thayer Mahan’s treatise on the necessity of naval power. The United States was pursuing an “Open Door” policy in China, and the possession of coaling stations was imperative to a would-be Pacific power. Benevolent Assimilation • Imperialism was difficult to square with the country’s republican tradition, as the noisy Anti-Imperialist League kept reminding Americans. US leaders also had to contend with the likes of Mabini and other ilustrados, despite the prevailing lens of racism that tended to see Filipinos as uncivilized or savage. This difficult reality compelled the new colonizers to demonstrate that their rule would be better than Spain’s or that of any European power. • The result was President McKinley’s “benevolent assimilation” – the American promise to train Filipinos in democratic governance until they were “ready” to govern themselves. But the first order of business was to achieve control over the country. 1896 1897 1898 August 23 March 4 February 9 February 15 Philippine Revolution Begins William McKinley inaugurated 25th President of the United States De Lome’s letter came out of the press The American battleship Maine exploded near the port of Havana. Out of the 350 passengers, 266 died and many others were wounded. April 11 April 16 April 23 April 25 McKinley asked Congress to declare war. Army began mobilization. Teller Amendment was passed in Congress stating that the US would not annex Cuba. McKinley issued call for 125,000 volunteers. Spain declared war US declared war with Spain but made the declaration retroactive to April 22 April 27 Commodore Dewey’s squadron left Mirs Bay, China for the Philippines. May 1 Dewey defeated the Spanish Armada in the Battle of Manila Bay. May 19 May 25 Emilio Aguinaldo returned from exile. McKinley issued a call for 75,000 more volunteers. The first army expedition left San Francisco for Manila. Aguinaldo issued a proclamation establishing a revolutionary government and a message to foreign powers announcing that government. June 18 June 30 August 12 The first batch of American soldiers arrived in Manila under the command of Brig. General Thomas M. Anderson. Spain and the US signed the peace protocol which ended the war. August 13 September 15 December 10 Capitulation of Manila to the Americans. Filipino Congress met at Malolos US and Spain signed the Treaty of Paris 1899 1900 January 22 Malolos Constitution was promulgated February 4 Filipino-American was began March 31 Malolos fell into the hands of the Americans. August 29 General Elwell Otis succeeded General Merritt in command. May 2 The Schurman Commission arrived in Manila November 13 Aguinaldo disbanded the organized army and resorted to guerilla warfare. May 5 General Arthur McArthur succeeded General Merritt as commander of the American army. June 3 The Taft Commission arrived in Manila. June 21 General McArthur issued a proclamation of amnesty to all who renounced the Filipino aspiration for independence and accepted American rule. 1901 1902 March 10 The Taft Commission conducted provincial sorties in Southern Luzon. They visited 18 provinces and returned to Manila on May 3. March 23 Aguinaldo was captured in Palanan, Isabela. April 1 The Commission issued a decree that property and funds of the insurgents would be confiscated if they did not surrender and that they be deprived of any position in the government, “no peace no job.” April 19 Aguinaldo swore allegiance to the US government. July 4 Taft was inaugurated first civil governor of the Philippines and General Chaffee replaced General McArthur. August The Taft Commission conducted another provincial sortie to establish civil government in several towns in Northern Luzon. August 21 The military transport S.S. Thomas arrived in Manila with 540 American school teachers aboard. September 6 President McKinley was shot in Buffalo, New York and died after eight days (September 14) September 28 Forty four American soldiers were massacred in Balangiga, Samar the worst blow to the American campaign in the Philippines. April 27 Vicente Lukban, the last recognized rebel leader was captured. July 4 President Roosevelt declared the Philippines pacified and granted amnesty to rebels. Military rule formally ended. December 23 Taft left Manila to succeed Elihu Root as Secretary of War. While the determined but poorly organized forces under President Aguinaldo were defeated by superior military arms, the Filipino people’s commitment to national independence was slowly drained by disease and hunger. To this was added the breakdown of the revolutionary leadership. Once provincial elites understood that the US was offering them the opportunity to run a state free from friar control – all that many had asked of Spain – there was little to hold them to the goal of independence. President McKinley dispatched a Philippine Commission to Manila in 1900 to meet with educated Filipinos and determine a form of government for the colony. Many “men of substance” testified before the committee on the need for American sovereignty in this country for the good of these “ignorant and uncivilized people.” This first group of collaborators soon formed a political party that positioned itself as pragmatically nationalists. UNITED STATES COLONIAL RULE IN THE PHILIPPINES The United States exercised formal colonial rule over the Philippines, its largest overseas colony, between 1899 and 1946. American economic and strategic interests in Asia and the Pacific were increasing in the late 1890s in the wake of an industrial depression and in the face of global, interimperial competition. Spanish colonialism was simultaneously being weakened by revolts in Cuba and the Philippines, its largest remaining colonies. UNITED STATES COLONIAL RULE IN THE PHILIPPINES The Philippine Revolution of 1896 to 1897 destabilized Spanish colonialism but failed to remove Spanish colonial rule. The leaders of the revolution were exiled to Hong Kong. When the United States invaded Cuba and Puerto Rico in 1898 to shore up its hegemony in the Caribbean, the U.S. Pacific Squadron was sent to the Philippines to advance U.S. power in the region, and it easily defeated the Spanish navy. Filipino revolutionaries hoped the United States would recognize and assist it. Although American commanders and diplomats helped return revolutionary leader Emilio Aguinaldo (1869— 1964) to the Philippine Islands, they sought to use him and they avoided recognition of the independent Philippine Republic that Aguinaldo declared in June 1898. UNITED STATES COLONIAL RULE IN THE PHILIPPINES In August 1898 U.S. forces occupied Manila and denied the Republic’s troops entry into the city. That fall, Spain and the United States negotiated the Philippines’ status at Paris without Filipino consultation. The U.S. Senate and the American public debated the Treaty of Paris, which granted the United States “sovereignty” over the Philippine Islands for $20 million. The discussion emphasized the economic costs and benefits of imperialism to the United States and the political and racial repercussions of colonial conquest. UNITED STATES COLONIAL RULE IN THE PHILIPPINES When U.S. troops fired on Philippine troops in February 1899, the Philippine-American War erupted. The U.S. Senate narrowly passed the Treaty of Paris, and the U.S. military enforced its provisions over the next three years through a bloody, racialized war of aggression. Following ten months of failed conventional combat, Philippine troops adopted guerrilla tactics, which American forces ultimately defeated only through the devastation of civilian property, the “reconcentration” of rural populations, and the torture and killing of prisoners, combined with a policy of “attraction” aimed at Filipino elites. While Filipino revolutionaries sought freedom and independent nationhood, a U.S.-based “anti-imperialist” movement challenged the invasion as immoral in both ends and means. UNITED STATES COLONIAL RULE IN THE PHILIPPINES Carried out in the name of promoting “self-government” over an indefinite but calibrated timetable, U.S. colonial rule in the Philippines was characterized politically by authoritarian bureaucracy and oneparty state-building with the collaboration of Filipino elites at its core. The colonial state was inaugurated with a Sedition Act that banned expressions in support of Philippine independence, a Banditry Act that criminalized ongoing resistance, and a Reconcentration Act that authorized the mass relocation of rural populations. UNITED STATES COLONIAL RULE IN THE PHILIPPINES In the interests of “pacification,” American civilian proconsuls in the Philippine Commission, initially led by William Howard Taft (1857-1930), sponsored the Federalista Party under influential Manila-based elites. The party developed into a functioning patronage network and political monopoly in support of “Americanization” and, initially, U.S. statehood for the Philippines. When the suppression of independence politics ended in 1905, it gave rise to new political voices and organizations that consolidated by 1907 into the Nationalista Party, whose members were younger than those of the Federalista Party and rooted in the provinces. When the Federalista Party alienated its American patrons and its statehood platform failed to win mass support, U.S. proconsuls abandoned it for the Nationalista Party, which over the remainder of the colonial period developed into a vast, second party-state, under the leadership of Manuel Quezon (1878-1944) and Sergio Osmena (1878-1961). American Soldiers in the Philippines, 1899. American soldiers fire their rifles from behind a makeshift barricade at the West Beach Outpost in San Roque during the Philippine insurrection that followed the 1898 Spanish-American War. UNITED STATES COLONIAL RULE IN THE PHILIPPINES Following provincial and municipal elections, “national” elections were held in 1907 for a Philippine Assembly to serve under the commission as the lower house of a legislature. The 3 percent of the country’s population that was given the right to vote swept the Nationalistas to power. The Nationalistas clashed with U.S. proconsuls over jurisdiction and policy priorities, although both sides also manipulated and advertised these conflicts to secure their respective constituencies, masking what were in fact functioning colonial collaborations. Democratic Party dominance in the United States between 1912 and 1920 facilitated the consolidation of the Nationalista partystate in the Philippines. UNITED STATES COLONIAL RULE IN THE PHILIPPINES When Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924), a Democrat, was elected president in 1912, he appointed as governor-general Francis Burton Harrison (1873-1957), who, working closely with the Nationalistas, accelerated the “Filipinization” of the bureaucracy and allowed the Philippine Assembly to assume additional executive power. When Democrats passed the Jones Act in 1916, which replaced the commission with a Philippine senate and committed the United States to “eventual independence” for the Philippines, Quezon claimed credit for these victories and, despite his own ambivalence about Philippine independence, translated them into greater power. During the 1920s, Quezon dominated the Nationalista Party, using clashes with Republican governor-general Leonard Wood (1860-1927) to secure his inde-pendista credentials. UNITED STATES COLONIAL RULE IN THE PHILIPPINES Under pressure from protectionists, nativists, and military officials fearful of Japanese imperialism, the U.S. Congress passed the Tydings-McDuffie Act in 1934. The act inaugurated a ten-year ”Philippine Commonwealth” government transitional to ”independence.” While serving as president of the commonwealth in the years prior to the 1941 Japanese invasion of the Philippine Islands, Quezon consolidated dictatorial power. Colonial political structures, constructed where the ambitions and fears of the Filipino elite connected with the American imperial need for collaborators, had successfully preserved the power of provincial, landed elites, while institutionalizing this power in a countrywide ”nationalist” politics. UNITED STATES COLONIAL RULE IN THE PHILIPPINES In economic terms, American colonial rule in the Philippines promoted an intensely dependent, export economy based on cash-crop agriculture and extractive industries like mining. American capital had initially regarded the Philippines as merely a ”stepping stone” to the fabled China market, and American trade with the Philippine Islands was initially inhibited by reciprocity treaties that preserved Spanish trade rights. When these rights ended, U.S. capital divided politically over the question of free trade. American manufacturers supported free trade, hoping to secure in the Philippines both inexpensive raw materials and markets for finished goods, whereas sugar and tobacco producers opposed free trade because they feared Philippine competition. The Payne-Aldrich Tariff of 1909 established ”free trade,” with the exception of rice, and set yearly quota limits for Philippine exports to the United States. UNITED STATES COLONIAL RULE IN THE PHILIPPINES American trade with the Philippine Islands, which had grown since the war, boomed after 1909, and during the decades that followed, the United States became by far the Philippines’ dominant trading partner. American goods comprised only 7 percent of Philippine imports in 1899, but had grown to 66 percent by 1934. These goods included farm machinery, cigarettes, meat and dairy products, and cotton cloth. The Philippines sold 26 percent of its total exports to the United States in 1899, and 84 percent in 1934. Most of these exports were hemp, sugar, tobacco, and coconut products. UNITED STATES COLONIAL RULE IN THE PHILIPPINES Free trade promoted U.S. investment, and American companies came to dominate Philippine factories, mills, and refineries. When a post-World War I economic boom brought increased production and exports, Filipino nationalists feared economic and political dependence on the United States, as well as the overspecialization of the Philippine economy around primary products, overreliance on U.S. markets, and the political enlistment of American businesses in the indefinite colonial retention of the Philippine Islands. UNITED STATES COLONIAL RULE IN THE PHILIPPINES Meanwhile, rural workers subject to the harsh terms of export-oriented development challenged the power of hacienda owners in popular mass movements. While some interested American companies did lobby against Philippine independence, during the Great Depression powerful U.S. agricultural producers—especially of sugar and oils— supported U.S. separation from the Philippines as a protectionist measure to exclude competing Philippine goods. The commonwealth period and formal Philippine independence would be characterized by rising tariffs and the exclusion of Philippine goods from the U.S. markets upon which Philippine producers had come to depend. Protectionist Empire Trade, Tariffs and US Foreign Policy 1890-1914 Abstract • 25 years before WW1, US involved itself in international politics acquiring overseas colonies, building a battleship fleet and intervening increasingly often in Latin America. • It believes that foreign markets were necessary for the prosperity of US. • It protects home market from foreign competition Abstract • Republican party strongly committed to Trade protection. • Republican policy makers focus on less developed areas of the world that would not export manufactured goods to the US rather than on wealthier markets in Europe. • US seeks exclusive unilateral or bilateral trade concessions with individual trading partners instead of accepting multilateral arrangements that would have resulted in lower tariffs. 25 years before WW1 • Remembered as the era when the US became a major power in international politics. • The scope of American foreign policy ambition greatly increased • US acquired colonies in the Philippines, Guam and Puerto Rico in 1898 as a result of Spanish-American war. • American presidents broadened their interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine’s injunction against European intervention in the American while taking diplomatic and military actions in other countries. 25 years before WW1 • US military and diplomatic bureaucracy expanded 1890 – 76 employees in Washington 1910 – 234 1890 – army/navy – 39,000 soldiers and sailors 1914 – 166,000 • What role did the Americans take in international trade play in shaping foreign policy? Noted historians William Williams, Watler LaFebes and others have argued that there was an elite consensus on the need for foreign markets. 25 years before WW1 • Americans worried about the social and political implication of the falling prices and the periodic economic crisis of the late 19th century. • Rapid economic growth after the Civil War was producing more than the home market could consume at price levels that provided reasonable profits to producers. • Americas solution was to find foreign markets for their ‘surplus production’ • The challenges of insuring access to markets in Asia and Latin America explain much of American foreign policy during this period. 25 years before WW1 • American policy makers preferred to rely on diplomatic and economic instruments but willing to use force when necessary to overcome resistance from economic nationalists in less developed countries on rival major powers seeking to create exclusive economic and political empires for themselves. • 1890-1914 period saw the political importance of overseas markets. Tariff was critically important political issue. It was critically important and divisive political issues. Republicans favored a protective tariff on manufactured goods. Democrats prefer lower barrier to imports. • Unlike the search for export markets, the import side of the story is not one of consensus but of partisan political conflict. 25 years before WW1 • Alongside the demand for foreign markets, the dominant Republican Party’s commitment to protectionism influenced the policy choices its leaders made. • It prompted them to emphasize markets in less developed areas that would not export manufactured goods to the US. • American empire of this period was a Protectionist Empire. • Brook Adams, one of the most prescient (visionary) writers of this period did not simply downplay security concerns in favor of economic interest. 25 years before WW1 • They argued that economic concerns defined security threats and interests. • International political conflicts were fundamentally quarrels over economic stakes, especially access to markets. • Elite discourse about the role of foreign markets in insuring internal social stability in the face of ‘overproductions’ and falling prices were extensively documented. • Control of international commerce was crucial for US domestic economy’s need for foreign markets. 25 years before WW1 • Whether based on concern about domestic political and social stability or international competitiveness, the bottomline was that the US needed access to foreign markets. • In late 19th century, access to foreign markets was not simply a private concern for traders and investors. It also had major foreign policy implications. • The imperialism of Trade, the politicomilitary control over market access for US citizens. • American leaders’ interest in increasing the country’s exports led them to adopt a policy of political and military intervention overseas. Reference: Escalante, Rene R. The Bearer of Pax Romana: The Philippine Career of William H. Taft, 1900-1903. New Day Publishers. Quezon City. 2007. Abinales, Amoroso. State and Society. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc., Lanham, MD. Anvil Publishing Inc., 2005. Manila. Photo: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Philippines_(1898%E2%80%931946)