Randomisation methods

advertisement

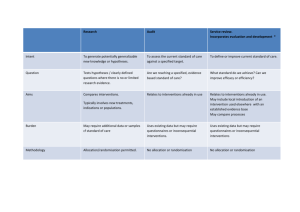

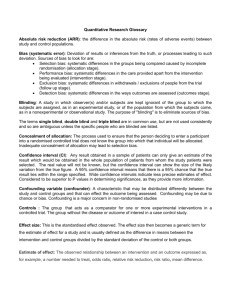

Allocation Methods David Torgerson Director, York Trials Unit djt6@york.ac.uk www.rcts.org Randomised Trials • The ONLY distinguishing feature of a RCT is that 2 or more groups are formed by random allocation. • All other things, blinding, theoretical justification for intervention, baseline tests may be important but are not sufficient for a study to be a RCT. Rejected paper It purports to be a randomized controlled trial, but it demonstrates none of the attributes of one. As a result, I recommend that this article be rejected for publication. Educational research should begin with a theory, a causal argument, based on a careful examination of the literature. We need to understand in an experiment why such an approach would be examined, the historical linkages of past research to present investigations. What conditions would lead one to believe that this technology could make a difference in spelling? Is it something in the software, on the computer screen, on children's interaction with the particular curriculum. This is often the most important part of a study, the question, and the rationale for why the investigation is critically important. What Randomisation is NOT • Randomisation is often confused with random SAMPLING. • Random sampling is used to obtain a sample of people so we can INFER the results to the wider population. It is used to maximise external or ecological validity. Random Sampling • If we wish to know the ‘average’ height and weight of the population we can measure the whole population. • Wasteful and very costly. • Measure a random SAMPLE of the population. If the sample is RANDOM we can infer its results to the whole population. If the sample is NOT random we risk having biased estimates of the population average. Why do we randomise? • • • • (1) Avoid selection bias (2) Controls for temporal effects (3) Controls for regression to the mean (4) Basis for statistical inference Random Allocation • Random allocation is completely different. It has no effect on the external validity of a study or its generalisability. • It is about INTERNAL validity the study results are correct for the sample chosen for the trial. Comparable Groups • It has been known for centuries to to properly evaluate something we need to compare groups that are similar and then expose one group to a treatment. • In this way we can compare treatment effects. • Without similar groups we cannot be sure any effects we see are treatment related. Why do we need comparable groups? • We need two or more groups that are BALANCED in all the important variables that can affect outcome. • Groups need similar proportions of men & women; young and old; similar weights, heights etc. • Importantly, anything that can affect outcome we do NOT know about needs to be evenly distributed. Non-random methods: Alternation • Alternation is where trial participants are alternated between treatments. • EXCELLENT at forming similar groups if alternation is strictly adhered to. • Problems because allocation can be predicted and lead to people withholding certain participants leading to bias. Non-Random Methods Quasi-Alternation • Dreadful method of forming groups. • This is where participants are allocated to groups by month of birth or first letter of surname or some other approach. • Can lead to bias in own right as well as potentially being subverted. Randomisation • Randomisation is superior to non-random methods because: » it is unpredictable and is difficult for it to be subverted; » on AVERAGE groups are balanced with all known and UNKNOWN variables or covariates. Methods of Randomisation • • • • • Simple randomisation Stratified randomisation Paired randomisation Pairwise randomisation Minimisation Simple Randomisation • This can be achieved through the use of random number tables, tossing a coin or other simple method. • Advantage is that it is difficult to go wrong. Simple Randomisation: Problems • Simple randomisation can suffer from ‘chance bias’. • Chance bias is when randomisation, by chance, results in groups which are not balanced in important co-variates. • Less importantly can result in groups that are not evenly balanced. Other reasons? • Clinicians don’t like to see unbalanced groups, which is cosmetically unattractive (even though ANCOVA will deal with covariate imbalance) • Historical – Fisher had to analyse trials by hand, multiple regression was difficult so pre-stratifying was easier than poststratification. Stratification • In simple randomisation we can end up with groups unbalanced in an important co-variate. • For example, in a 200 patient trial we could end up with all 20 diabetics in one trial arm. • We can avoid this if we use some form of stratification. Blocking and stratification • To stratify we must use some form of restricted allocation – usually blocking. • One CANNOT stratify unless the randomisation is restricted. Blocking • A simple method is to generate random blocks of allocation. • For example, ABAB, AABB, BABA, BBAA. • Separate blocks for patients with diabetes and those without. Will guarantee balance on diabetes. Blocking and equal allocation • Blocking will also ensure virtually identical numbers in each group. This is NOT the most important reason to block as simple allocation is unlikely to yield wildly different group sizes unless the sample size is tiny. Blocking - Disadvantages • Can lead to prediction of group allocation if block size is guessed. • This can be avoided by using randomly sized blocks. • Mistakes in computer programming have led to disasters by allocating all patients with on characteristics to one group. Pairing • A method of generating equivalent groups is through pairing. • Participants may be matched into pairs or triplets on age or other co-variates. • A member of each pair is randomly allocated to the intervention. Pairing - Disadvantages • Because the total number must be divided by the number of groups some potential participants can be lost. • Need to know sample in advance, which can be difficult if recruiting sequentially. • Loses some statistically flexibility in final analysis. Pairwise randomisation • Sometimes we want to balance allocation or make it predictable by centre to ensure resources are fully utilitised (e.g., surgical slots). Stratified randomisation by centre increases predictablility. • An alternative is to recruit at least 2 participants at a time and then randomise 1 to the intervention – note this not the same as matched or paired randomisation. Non-Random Methods Minimisation • Minimisation is where groups are formed using an algorithm that makes sure the groups are balanced. • Sometimes a random element is included to avoid subversion. • Can be superior to randomisation for the formation of equivalent groups. Minimisation Disadvantages • Usually need a complex computer programme, can be expensive. • Is prone to errors as is blocking. • In theory could be subverted. Example of minimisation • We are undertook a cluster RCT of adult literacy classes using a financial incentive. There were 29 clusters we want to be sure that these are balanced according to important co-variates: size; type of higher education; rural or urban; previous financial incentives. How does it work? • The first few classes are randomly allocated. • After this we calculate a simple score based on our covariates to achieve balance. Which covariates? • We wanted to ensure the trial was balanced on the following: » Type of institution (FE or other); » Location (rural or urban); » Size of class (<8 or 8+) » Previous use of incentives (yes or no). 28 randomised Covariate FE Other Rural Urban 8+ <8 Incentive No Intervention 6 8 5 9 5 9 2 12 Control 8 6 6 8 6 8 1 13 th 29 class • This class has the following characteristics: » Not FE; » Urban » Large (8+) » No previous incentive. Covariate FE Other Rural Urban 8+ <8 Incentive No Total Intervention Control 6 8 5 9 5 9 2 12 34 8 6 6 8 6 8 1 13 33 th 29 Class • Because the control group has the lowest number 33 the 29th class is allocated to this and not the intervention. • This will balance the groups across all the covariates. • If the totals are the same then randomisation is used. Outcomes of Trial • Our main aim was to see if incentives would increase the number of sessions attended. • The results was that on average 1.53 FEWER sessions were attended in the intervention group than the control (95% CIs 0.28, 2.79; p = 0.019). Allocation – current practice • In 2002 Hewitt et al, identified 232 RCTs in the: BMJ; JAMA; Lancet; New Engl J Med. • Only 19 (8%) used simple unrestricted randomisation. Types of Allocation in 4 general medical journals Minimisation 17 (7.3%) Block size small and fixed 50 (21.6%) Block size large and fixed 18 (7.8%) Block size mixed 15 (6.5%) Block size random 5 (2.2%) Block size unclear 27 (11.6%) Simple 21 (9.1%) Unclear 79 (34.1 %) Total 232 Confused trialists? • “randomisation was done centrally by the coordinating centre. Randomisation followed computer generated random sequences of digits that were different for each centre and for each sex, to achieve centre and sex stratification. Blocking was not used”. (Durelli et al) • “randomisation was stratified according to the hospital and tumour site (esophagus or cardia). No blocking was used within each of the four strata”. (Hulsher et al). Durelli et al, Lancet 2002;359:1453-1460 Hulsher et al, NEJM 2002; 2002;347:1662-1669 Conclusions • Random allocation is USUALLY the best method for producing comparable groups. • Simple randomisation is usually best for large samples sizes (e.g., 100+ allocation units) • Alternation even if scientifically justified will rarely convince the narrow minded evidence based fascist that they are justified. • Some health service researchers as well as clinicians are still resistant to the idea of random allocation.