Assessment and management of pain near the end of life

advertisement

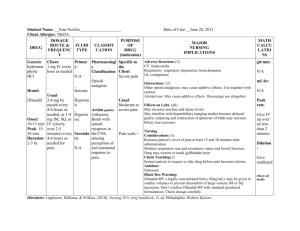

Assessment and management of pain near the end of life David Casarett MD MA University of Pennsylvania Goal: To describe an evidence-based approach to pain management near the end of life, with a focus on: » Assessment » Defining goals for care and enpoints of pain management » Use of opioids • Appropriate use of opioids • Managing opioid-related side effects » Beyond pain management: the role of hospice in long term care Audience: Clinicians in long term care: » Physicians » RNs » Advance Practice Nurses Surveyors Quality Improvement leaders Case: Mr. Palmer is an 84 year old man with moderate dementia (MMSE=15), severe peripheral vascular disease and coronary artery disease. He currently lives in a nursing home, where he is dependent on others for most activities of daily living. He is able to speak in short sentences and can participate in health care decisions in a limited way. His daughter discusses his care with him, but ultimately makes all decisions for him. Case, part 2 He suffers a fall that results in a fracture of the left hip and is evaluated in a hospital emergency room. Because of his other medical conditions, high operative risk, and poor quality of life, his daughter decides with Mr. Palmer that he would not want to undergo surgery and instead would prefer to be kept comfortable. He returns to the nursing home with a plan for comfort care, with an emphasis on pain management. Outline Scope of the problem: pain near the end of life in nursing homes Assessment » Background » Principles of assessment Management » Establishing goals of care » Defining endpoints of pain management » Opioids-the mainstay of pain management near the end of life • Use of opioids • Management of side effects Beyond pain management: the role of hospice in the nursing home Scope of the problem: pain near the end of life in nursing homes Defining the “end of life” » No established definition » 6 month prognosis (hospice eligibility) not useful • Arbitrary • Difficult to determine accurately » Instead: A resident is near the end of life if he/she has a serious illness that is likely to result in death in the foreseeable future Operationalize as: “Would I be surprised if this resident were to die in the next year?” (Joanne Lynn) Mr. Palmer: Would not be surprised—peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease, dementia, recent hip fracture. Scope of the problem: Common serious illnesses in the nursing home Cancer* Dementia* Stroke* Peripheral Vascular Disease* Falls/Hip fracture* Congestive Heart Failure Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Cirrhosis *Associated with pain Prevalence of pain (all diagnoses) Depends: » Surveys: 30-71% » Medication audits: 25-50% Hospice (Pain requiring intervention) » 25% (Casarett 2001) What is the primary cause of pain? Low back pain 40% Previous fractures 14% Neuropathy 11% Leg cramps 9% DJD (knee) 9% Malignancy 3% (Ferrell et al JAGS 1990) What are the characteristics of pain in the nursing home? Intermittent Constant None (Ferrell et al JAGS 1990) Room for improvement? Undetected in 1/3 (Sengstaken and King 1993) Undertreated (Bernabei et al 1998) Both (cognitively impaired) (Horgas and Tsai 1998) Pain assessment Adapted from AGS Persistent Pain Guidelines Comprehensive pain assessment: History 1. Evaluation of Present Pain Complaint 1. Self-report 2. Provider/family reports 2. Impairments in physical and psychosocial function 3. Attitudes and beliefs/knowledge 4. Effectiveness of past pain-relieving treatments 5. Satisfaction with current pain treatment/concerns Comprehensive pain assessment: Objective data 1. Careful exam of site, referral sites, common pain sites 2. Observation of physical function 3. Cognitive impairment 4. Mood 5. Limited role for imaging 1. May be useful 2. Often will not change management Special situations: Mild to moderate cognitive impairment Direct query Surrogate report only if patient cannot reliably communicate Use terms synonymous with pain (“hurt” “sore”) Ensure understanding of tool use » Give time to grasp task and respond and repetition Ask about present pain Ask about and observe verbal and nonverbal pain-related behaviors and changes in usual activities/functioning Use standard pain scale, if possible » 0-10 Numeric Rating Scale » *Verbal Descriptor/Pain Thermometer » Faces Pain Scale Numeric Rating Scale 0 No pain 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Worst possible pain Verbal Descriptor Scales Verbal Descriptor Scale (VDS) ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ Most Intense Pain Imaginable Very Severe Pain Severe Pain Moderate Pain Mild Pain Slight Pain No Pain (Herr et al., 1998) Present Pain Inventory (PPI) 0 = No pain 1 = Mild 2 = Discomforting 3 = Distressing 4 = Horrible 5 = Excruciating (Melzack 1999) Pain Thermometer Pain as bad as it could be Extreme pain Severe pain Moderate pain Mild pain Slight pain No pain (Herr and Mobily, 1993) Advantages of verbal descriptor scales Data suggest that patients may be more likely to be able complete verbal descriptor scales (Ferrell 1995;Closs 2004) May be less sensitive to cognitive impairment/visual impairment But, no “one size fits all” scale Facial Pain Scales Faces Pain Scale Bieri D et al. Pain. 1990;41:139-150. Principles of assessment: mild/moderate cognitive impairment The “best” assessment method is the one that the patient can use This is often, but not always, a verbal descriptor scale Use the same instrument/scale consistently Use it in the same way Special situations: Moderate to severe cognitive impairment Direct observation or history for evidence of pain-related behaviors (during movement, not just at rest) Facial expressions of pain (grimacing) » Less specific: slight frown, rapid blinking, sad/frightened face, any distorted expression Vocalizations (crying, moaning, groaning) » Less specific: grunting, chanting, calling out, noisy breathing, asking for help Body movements (guarding) » Less specific: rigidity, tense posture, fidgeting, increased pacing, rocking, restricted movement, gait/mobility changes such as limping, resistance to moving Moderate to severe cognitive impairment Unusual behavior should trigger assessment of pain as a potential cause » Caveat: Some patients exhibit little or no pain-related behaviors associated with severe pain Always consider whether basic comfort needs are being met “Pre-test probability” Evidence of pathology that may be causative (e.g. infection, constipation, fracture)? Attempt an analgesic trial » If in doubt, analgesic trial may be diagnostic » Acetaminophen 500mg TID, (titrate up to 3-4G/day) Principles of assessment: moderate/severe cognitive impairment No single optimal method (no “gold standard”) Assessment requires several sources of information (observations of several providers, family) Many “pain-related behaviors” are non-specific If no known cause of pain, trial of acetaminophen can be useful If reason for pain, empirical treatment is appropriate Pain management Principles of pain management Defining goals of care Defining endpoints of pain management Opioids-the mainstay of pain management near the end of life » Use of opioids » Management of side effects Beyond pain management: the role of hospice in the nursing home Individualized care planning: Defining goals of care Highly variable goals for care: » Comfort » Function » Survival Highly variable preferences about: specific management choices » » » » Site of care Treatment preferences (e.g. DNR, transfer to hospital) Site of death Optimal balance of pain, sedation, and other medication side effects Treating pain in a resident with these goals…. Cure of disease Maintenance or improvement in function Prolongation of life Or treating pain in a resident with these goals…. Relief of suffering Quality of life Staying in control A good death Support for families and loved ones The importance of defining goals of care Cure of disease Maintenance or improvement in function Prolongation of life Relief of suffering Quality of life Staying in control A good death Support for families and loved ones Individualized care planning: 2 examples Mr. Palmer’s daughter accepts that there are no further treatment options available to extend life. She says it is most important for her father to avoid pain or discomfort. » Aggressive pain management » Family support » Hospice Mr. Palmer’s daughter says that he would want any treatment that might improve his survival and maintain the function he has left. She says he wants aggressive treatment even if it results in discomfort. » Surgical intervention » Aggressive physical therapy Curative / Life-prolonging Therapy Course of illness Relieve Suffering (Palliative Care and hospice) Challenges of defining goals of care accurately Interpreting resident statements Multiple disciplines=multiple interpretations » (Importance of clear documentation) Conflicting resident/family goals Uncertainty about resident decision-making capacity Changes in goals over time (resident and family) Inconsistent preferences or goals (e.g. extending life but no transfer to acute care) Defining goals of care: principles Broad categories are most useful (survival, function, comfort, others that are residentdefined) Goals rather than treatment preferences (e.g. resuscitation status) Useful guides (not mutually exclusive): » Prolonging survival » Preserving function/independence » Maximizing comfort Case: Goals for care Mr. Palmer’s daughter accepts that there are no further treatment options available to extend life. She says it is most important for her father to avoid pain or discomfort. This plan is communicated to other family members and staff, and is clearly documented in the medical record Defining endpoints of pain management The optimal plan of pain management is one that: » Achieves an acceptable (to the patient) level of pain relief » Preserves an acceptable level of alertness and function » Offers an acceptable side effect profile Defining endpoints of pain management Usually not “no pain” Depends on: » Goals » Treatment preferences » Tolerance for side effects A note about assessing satisfaction Advantages: » Simple, easy to assess » Easy to interpret » Often encouraged by facility leadership Disadvantages: » Ceiling effect » Poor association with pain control » Confounded by other factors (Ward 1996, Desbiens 1996, Casarett 2002, Gordon 1996) • • • • Side effects prn dosing/control Ethnicity Depression Pain management near the end of life: focus on opioids Multiple strategies for the management of pain near the end of life Heat/cold TENS units Counseling Spiritual support NSAIDs/Acetaminophen Agents for neuropathic pain (e.g. tricyclic antidepressants, gabapentin) Opioids Key principles of management Opioids are mainstay of management Use of multiple pharmacological agents is often needed to provide optimal management: » » » » NSAIDs Tricyclic antidepressants Corticosteroids Anticonvulsants Traditional rules discouraging polypharmacy don’t apply in this setting: importance of individualized management. Why focus on opioids? Highly effective Underutilized Poorly understood by providers and public Common misconceptions Pain management near the end of life: the role of opioids The mainstay of effective pain management near the end of life Appropriate for residents with moderate or severe pain » 4/10 or greater, or » Conditions that are associated with moderatesevere pain (when resident is too cognitively impaired to permit an accurate assessment of severity) Addiction and other concerns about opioids Addiction: a syndrome of physical and psychological dependence » Very rare in opioid treatment near the end of life » Estimates of risk are <<1% Except in very unusual circumstances (e.g. history of drug dependence), concerns about addiction are not appropriate in the setting of pain management near the end of life Increases in opioid dose often attributed (incorrectly) to addiction Tolerance: Gradual decrease in sensitivity to opioid effects (pain relief and side effects) » Results in “dose creep” Disease progression Pseudo addiction: Increases in medication requests (particularly prn opioids) out of proportion to pain and/or medication hoarding, in the setting of significant discomfort » Often labeled as addiction/diversion » Much more likely to be due to fear of pain/slow nursing response to requests for prn meds/desire for more control over pain management » Managed by more aggressive pain management not by reducing/controlling opioids Using opioids: strategies for administration Non-invasive (oral//PEG tube/transdermal) administration is preferred Sustained release preferred for persistent pain Virtually all patients receiving sustained release opioids should have prn opioid available for “breakthrough” pain (typically 10% of the 24 SR dose) Strategies for administration Begin with immediate release preparation » Scheduled (cognitively impaired/severe pain) » prn Can increase every 6-8 hours (faster if using IV/SC administration) Titrate up in reasonable (proportional) steps (think in terms of 20-50% increases) Switch to a long-acting preparation when pain control is adequate but continue access to prn dosing If continued titration is needed, use prn doses to estimate additional opioid requirements Which opioid? Basic considerations Morphine: Inexpensive, widely available, and can be administered by multiple routes and schedules Hydromorphone: More potent, but no SR and limited routes of administration. Advantages in renal insufficiency. Oxycodone: SR available, also concentrated PO, but no IV. Possibly decreased risk of delirium in older patients. Methadone: inexpensive, available IV and PO. T1/2 is longer than duration of effect. Fentanyl patch: Convenient, conversion difficult, poor choice when rapid titration is needed. Which opioid? Overall, no evidence of one agent’s superiority with respect to: » Effectiveness » Side effects Choice based on: » Past experience » Clinician’s comfort/experience with an agent » Specific features of a resident’s case (e.g. need for rapid titration) Choosing an opioid in the setting of hepatic failure Opioid metabolism: » Hepatic metabolism/conjugation » Renal excretion Less desirable: » Codeine (Decreased conversion to morphine and decreased efficacy +/- increased side effects) » Methadone (decreased Phase I metabolism) • Liver • Gut metabolism and elimination (p-glycoprotein) (variable bioavailability in hepatic failure) Other (preferable) agents only have increased bioavailability: » » » » Oxycodone (decreased Phase I metabolism) Morphine (decreased Phase II conjugation) Hydromorphone (decreased Phase II conjugation) Fentanyl (decreased Phase I metabolism) Choosing an opioid in the setting of renal failure Minor concern: avoid agents with significant renal clearance: » Oxycodone » Fentanyl (Patch/infusion) » Methadone (>60 mg/day) More important: » Avoid agents with active metabolites that are renally cleared: • • • • Morphine Codeine Meperidine (never appropriate) Oxycodone(?): Noroxycodone and oxymorphone » And…select agents with inactive metabolites: • Fentanyl (norfentanyl) – No evidence of increased neuroexcitatory side effects • Hydromorphone (hydromorphone-3 glucuronide?) • Methadone Summary: renal and hepatic failure Theoretical reasons to select certain agents Although some agents are (theoretically) preferable in certain settings, no “right” or “wrong” choice Rules of thumb » If it’s not broke, don’t fix it (What appears to work for a particular patient is a “right” choice) » Dose escalation should be more conservative in renal/hepatic failure » Virtually any agent can be used effectively by “starting low and going slow” » When renal/hepatic failure is progressive, be prepared to reduce the opioid dose Choosing an opioid when PO intake is limited IV/SC route (morphine, hydromorphone, methadone) Transdermal (fentanyl) » Poor choice for rapid titration » Convincing evidence of ambient heat effect (Ashburn, 2002) » Not optimal when limited sc adipose tissue Rectal administration » Suppositories, liquid, or SR formulation (short term) » Bioavailability is probably 90-100% of oral route » First pass metabolism depends on site of absorption Microcapsule formulations of morphine (Kadian, Avinza) » Pudding/applesauce » PEG tube Liquid formulations of methadone (PEG tube) Limited PO intake: SC administration of opioids For most systems, SC morphine limit is 30 mg/hour For higher dose requirements hydromorphone is a good alternative (potent, can be concentrated) No need for hyaluronidase Butterfly needle/change q 5-7 days or with discomfort D5W preferred diluent Case: pain management Mr. Palmer received IV morphine in the ER that was titrated up to 5 mg/hour at the time of his transfer. This dose was maintained on transfer (His nurse asked Mr. Palmer’s physician for a verbal order for a laxative to prevent opioidinduced constipation. He was started on senna and colace BID.) Opioid-related side effects Side effects: » » » » » Sedation Nausea/emesis Delirium/confusion/agitation (Constipation) Myoclonus Opioid-induced side effects: Overview of options Opioid rotation Decrease dose Add symptomatic therapy Change route Opioid-related side effects: Sedation After 4 hours in the ER, Mr. Palmer’s pain is 6/10, and by 8 hours (after transfer) it’s a 3. He is resting comfortably, but is arousable. 6 hours later, his nurse notes that Mr. Palmer is not arousable, and will not respond to voice. Opioid-induced sedation: background Prevalence: up to 60% of patients, highest in initial days of therapy/changes in dose or route Differential diagnosis (extensive workup is often undesirable): » Sleep deprivation » Delayed effects of opioid » Other: • • • • Internal bleeding/hypotension Hepatic encephalopathy Pulmonary embolus Sepsis The therapeutic window Somnolence Pain control Time The therapeutic window Somnolence Pain control Time Opioid-induced sedation: (acute) management General strategies: » Assess respiratory status/airway » Reassure family/staff » Assess monitoring/nursing capacity Specific strategies: » Decrease dose » Wait… » Avoid naloxone (but bedside availability, 0.4 mg with 10 ml water, can offer psychological value) Opioid-induced sedation: (subacute) management Choice of route? (No good data to support independent route effect) Opioid rotation. Limited data (Most retrospective data) Methylphenidate » Poor database of studies enrolling carefully selected patients (Wilwerding et al 1995; Bruera 1987) » Evidence of some specific effectiveness but more global improvement in well-being Sedation algorithm Acute, no respiratory depression » If titrating up, change to maintenance dose, monitor » If already at maintenance dose, continue, wait >6 hours • At steady state • Reduced sleep deficit • Family/staff reassurance » Still sedated, consider decreased dose Subacute » Identify temporal relationships and opioid/pain mismatch » Assess nocturnal sleep, consider hypnotic » Assess pain control • Inadequateopioid rotation • Adequatemethylphenidate, 2.5 mg BID (AM and noon)10 mg and 5 mg Sedation: Outcome Mr. Palmer’s opioids were not increased further and he slept for 7 hours without breakthrough dosing. On awaking, his pain was well-controlled but required frequent breakthrough doses. Those doses were incorporated into his IV infusion over the next 24 hours and the infusion rate was increased with no further sedation. Opioid-related side effects: Nausea As you are titrating morphine gradually against pain, Mr. Palmer develops severe nausea with repeated vomiting. There is no associated abdominal pain, constipation, or melena. Bowel sounds are somewhat diminished but there is no evidence of distention. Opioid-induced nausea: background Occurs in up to 1/3 of patients Usually within first week of therapy Typically dose-independent Mechanisms of opioid-induced nausea: » » » » Chemoreceptors in CNS Impaired GI motility Vestibular stimulation Conditioning/anticipatory nausea Importance of ruling out related causes: » Disease-specific symptoms » Constipation or bowel obstruction » Opioid-induced vertigo (<5%) Opioid-induced nausea: management Limited data, not helpful to extrapolate from other common nausea syndromes (e.g. chemotherapy) Dose reduction unlikely to be effective Interventions: » Switch route (oralSC); limited data (McDonald 1991; Drexel 1989) » Opioid rotation; better data (de Stoutz 1995) » Symptomatic treatment… Symptomatic treatment options Haloperidol, prochorperazine (Dopamine antagonism in CTZ; Haloperidol has stronger dopamine effects) Metoclopramide (Peripheral pro-motility effects, antidopamine effects at higher doses, e.g. >10 mg q 6 hours) Scopolamine patch (purely anticholinergic effects) Also: » » » » Ondansetron (Sussman 1999) Lorazepam Benadryl Dexamethasone (Wang 1999) • Decreased BBB permeability? • GABA depletion and inhibition of the CTZ? Nausea algorithm Early, aggressive treatment with metoclopramide: » In outpatients: prescription for 8 doses with opioid prescription » Inpatients: Prophylactic or prn order Effective, no emesiscontinue and taper Ineffectivecontinue and add haloperidol » Effectivecontinue • Taper haloperidol • Then taper metoclopramide » Ineffectivecontinue • Rotate opioids • Consider switch in route Outcome: Nausea Metoclopramide prn was not effective and was increased to a scheduled dose with some relief. Simultaneous treatment with metoclopramide (10 mg QID) and haloperidol (0.5 mg/6 hours) was completely effective. Haloperidol was discontinued after 36 hours and metoclopramide was discontinued after 3 days with no recurrence of nausea. Opioid-related side effects: opioidinduced delirium Mr. Palmer’s pain was well-controlled at a new steady dose of morphine, but he becomes agitated later that night. He is yelling, trying to pull himself out of bed, and seems to be experiencing visual hallucinations. Opioid-induced delirium: background Long differential diagnosis list: electrolyte abnormalities, physiological causes, “terminal” delirium. Mechanisms of true opioid-induced delirium » Kappa, delta receptors » Metabolites of parent drug » Non-specific/pathway effects (e.g. diminished arousal, decreased orientation, altered sleep-wake cycle) Opioid-induced delirium: management Very weak evidence base for opioid-induced delirium (only extrapolated studies) Non-pharmacological interventions are promising (also extrapolated)(Inouye 1999) Interventions: » » » » Reduce opioid dose(?) Opioid rotation: best data (de Stoutz 1995) Donepezil(?) Second generation antipsychotics: Strong theoretical rationale, anecdotal data, data extrapolated from other settings. Delirium algorithm Inadequate pain management » Distressing/agitated delirium opioid rotation + symptomatic therapy (low dose haloperidol, olanzapine, resperidone) » Not distressing/ “quiet” delirium opioid rotation, followed by symptomatic therapy if rotation not effective Adequate pain management » Add symptomatic therapy, consider opioid rotation if not effective Balancing pain management and side effects Confusion is an expected side effect of opioid therapy However, inadequate treatment of pain can produce syndromes of confusion, including delirium (Morrison 2003) Therefore, confusion/delirium in the setting of opioid management… » » » » Should not be considered as an adverse event Should not dissuade use of opioids Should not prompt discontinuation Should be managed carefully Delirium: Outcome Mr. Palmer’s agitation responded well to 0.5 mg haloperidol PO every 4-6 hours, with higher doses at bedtime. Additional interventions included: » » » » Move to private room Designated CNA (continuity) Pictures of family Promote normalized sleep-wake cycle through interaction during the day Opioid-induced side effects: general principles of management Assess pain management: » Inadequate pain managementOpioid rotation » Adequate pain management Consider effectiveness of available symptomatic therapy: • Reasonable data: Add symptomatic therapy • Weak data: consider dose reduction/opioid rotation NOTE: Effective treatment of side effects often requires additional medications AllConsider a change of route Beyond pain: the total care of residents and families near the end of life Mr. Palmer’s pain and side effects are adequately managed on a stable medication regimen. However, his interdisciplinary team identifies several additional problems, including: » Dry, cracked lips » Rapid breathing that they are concerned might be due to shortness of breath » Frequent crying spells in one staff member who had been very close to Mr. Palmer for the last 5 years » The daughter’s apparently depressed mood and expressions of guilt about “letting my father die” Beyond pain management Pain is only one aspect of end of life care Residents with pain usually have other physical symptoms Psychological symptoms are also common Grief and bereavement needs are common among family, staff, and other residents » After a residents death » Before the resident’s death (anticipatory grief) Pain management in the nursing home: the role of hospice Program of care designed to provide comprehensive care to patients near the end of life and their families Eligibility requires patients have a prognosis of 6 months or less and that they forgo curative treatment Over 3100 hospice organizations serve almost 900,000 patients annually • The Hospice team: Hospice physicians; Nurses; Home health aides; Social workers; Clergy or other counselors; Trained volunteers; Other disciplines, if needed. • Medications related to hospice DX • Bereavement follow up and counseling as needed for 1 year A role for hospice in nursing homes Strong evidence supporting the value of hospice in nursing homes (Miller 2001, Casarett 2001, Miller 2002, Miller 2001b, Baer 200, Teno 2004) » » » » » More services Better pain management Decreased restraint use Decreased hospitalization Better family satisfaction A role for hospice in nursing homes But nursing home residents are underrepresented in hospice » Payment barriers » Barriers created by institutional culture Lengths of stay are very short (median=26 days) » 1/3 enroll in last week » 10% enroll in last day Need for greater hospice access in nursing homes: » Access for more residents » Access earlier in the course of illness. The role of hospice in the nursing home Mr. Palmer’s family enrolled him in hospice, using a community hospice agency that came to the nursing home. Initial interventions included: » Adjustments to pain medication dosing schedule to achieve more even control » Mouth swabs » Oxygen and room fan to alleviate sensation of dyspnea » Counseling for both staff and daughter Mr. Palmer died 2 weeks later in the nursing home, without apparent discomfort.