Joining isn*t Everything: Exit, Voice, and Loyalty in Party Organizations

advertisement

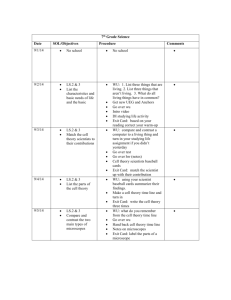

Joining isn’t Everything: Exit, Voice, and Loyalty in Party Organizations Emilie van Haute – Cevipol, Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB) evhaute@ulb.ac.be – www.cevipol.be Paper prepared for the Workshop ‘Parties as Organizations and Parties as Systems’ 19-21 May 2011, Vancouver, Canada Very first draft – Please do not cite without the permission of the author Paper abstract Literature on party organizations at the grass-root level mainly focuses on the question of who joins parties, and why. Explanatory models have been developed, inspired by the literature on political participation. Whereas scholars questioned the motivations for joining a party, few researches have been performed on the reasons for remaining a member, or for leaving a party. Combining the idea that parties are miniature political systems, and Hirschman’s trilogy on organization, the paper suggest applying the concepts of exit, voice and loyalty to the study of party organizations. This question is of particular interest in a context of declining membership and questioning of the parties’ capacity to perform their essential functions in democracies. 1 Introduction European political parties have been recruiting members for over a century. However, ‘parties without partisans’ are conceivable today (Dalton & Wattenberg, 2001). Clearly, parties are changing, whether they are mutating, adapting or declining. This makes the study of party membership and its mechanisms, processes and evolutions crucial. Besides, party membership is at the crossroads of two prolific fields in political science (party organizations and political participation). One would therefore expect to find an abundant literature on the topic. However, until recently, scholars have not devoted much attention to the phenomenon (van Haute, 2009). The first developments concerned the general decline in party memberships, framed in the thesis of party decline. In return, this has made the question of who joins political organizations a question commanding considerable attention. The work of Seyd and Whiteley is a turning point in this respect (Seyd & Whiteley, 1992; Whiteley & Seyd, 1994). Since then, several scholars or teams have performed the same type of micro-level analysis in their national contexts1. Most of this literature is rather descriptive, with an emphasis on the socio-demographic and political profile of the respondents. When turning analytical, the literature is rooted mainly in the literature on models of political participation: the resource model (Verba, Nie & Kim, 1978), the socio-psychological model (Finkel, Muller & Opp, 1989), and the rational choice model (Whiteley & Seyd, 1996). Today, we have a better picture of who joins parties, why they do it, what opinions they hold. However, Heidar (2007) pointed out that our knowledge is still kaleidoscopic as the existing studies are generally one-party or one-country studies. Very little comparative work has been done so far. We share this plea for more comparative work. However, this comparative work would still be anchored in the theories of political participation. We argue that this leads to three weaknesses for a better understanding of party membership and party organizations. Firstly, because it is rooted in the theories of political participation, the existing literature on party membership does not contribute significantly to the understanding of parties as organizations. The focus is on the individual act of joining, and not on the relationship between the member and his/her party. Conversely, research on parties tends to focus on specific aspects of parties, generally along the lines of a functionalist divide (Dalton & Wattenberg, 2000): parties in government, in the electorate or as organizations (Reiter 2006). If the latter has known a theoretical revival in the mid1990s with the cartel party thesis (Katz & Mair 1995), we still have little empirical evidence on what is happening in the black box of party organizations. 1 See “Special Issue: Party Members and Activists”, Party Politics, 20/4, 2004. 2 Secondly, the contribution to the knowledge of political participation is in itself rather limited due to the survey method used to collect data. At most can we say that we know more about ex post reconstruction of the motives to join than about the process of joining itself. Indeed, the surveys are aimed at members who joined on average a long time ago. For example, in Belgium, the surveys show that members joined their party on average 24.8 years ago for the Flemish Christian Democrats (CD&V), 19.7 years ago for the Flemish Liberals (OpenVLD), and even 29.5 years ago for the Frenchspeaking socialists (PS). Studies have shown that the longer the retention period, the higher the expected bias due to respondent recall error (Biemer et al., 2004: 134). In our example, the probability of recall errors among the respondents is very high. Finally, the existing literature based on explanatory models for joining could be compared to fairy tales. We meet the characters, get to know them, learn how they met, fell in love and got engaged. But these studies end too often on a ‘happily ever after’ note. Like with fairy tale, some fundamental questions are left open: what happens after the engagement? Do they remain faithful to each other? Do they face crises? How do they cope with these tensions? Does the story end up in a divorce? The explanatory models for joining do not shed light on what’s happening inside the parties once members have joined. The reference to romance and fairy tales is seemingly trivial. However, it emphasizes indirectly the fact that party membership can (and, from our point of view, should) be studied with other theoretical frameworks than the theories of political participation. We argue that to capture this idea of relationship between the members and the party and to remedy to the other weaknesses of the existing literature, two complementary frameworks can be mobilized: theories rooted in social psychology, which investigate individual behaviours in relationships, groups and organizations, and studies of organizations rooted in labour economics and management. Therefore, this paper aims at proposing new theoretical tools for the study of party membership, which allow tackling these questions of loyalty, dissatisfaction, doubts, or criticism. The main goal is to better understand the mechanisms through which party members renew their membership, decide to stay or to leave the party organization. These processes and concepts sound surprisingly close to Hirschman’s model of exit, voice, and loyalty (1970). This paper discusses how Hirschman’s model can be mobilized to analyze party members and their relation to their political party. In order to do so, this paper first explores Hirschman’s contribution and its consecutive applications in various fields in social sciences, including political science. We then offer arguments on why and how to apply Hirschman’s framework to the study of party membership and party organizations. 3 Hirschman’s trilogy and consecutive applications The main thesis developed in Exit, voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States (1970) suggests that exit and voice are the two reactions from consumers to a reduction in quality of the product provided by an organization. The choice between exit and voice is partly a rationalistic decision where individuals evaluate the costs and benefits of their actions according to their own interests. But it is also influenced by a third concept, ‘loyalty’. Loyalty would prevent consumers from leaving the organization and favor protest. Hirschman’s contribution was qualified by Barry (1974) as the only book to fit to rank with Downs’ Economic Theory of Democracy (1957) and Olson’s Logic of Collective Action (1965). According to him, it stretched the economic approach outside its conventional topics, reached an ‘oecumenical spirit’, and opened new horizons for research. Each concept of the trilogy appealed to a specific domain. Economic analyzes concentrated on exit (customers stopping to buy a product, or employee turnover in firms). The study of voice opened the political dimension to the analysis (Kolarska & Aldrich, 1980: 42). Loyalty brought in the socio-psychological dimension of the model. Therefore, it is not surprising that the model has been used in various fields of research. The social-psychological literature used Hirschman’s work to study interpersonal and intergroup relations (Dowding et al., 2000). Research looked at dissatisfaction in social relations at work, in groups, or in couple relationships. The main contribution of these studies is the addition of a fourth category to the EVL model: Neglect, as well as the idea that responses to dissatisfaction can be constructive or destructive, or passive/active. In terms of methods, these studies have conducted empirical tests of the model and combined various methods (surveys, role-play methodologies, etc.). Their main weakness is the lack of theoretical discussion. Loyalty is seen as a form of behaviour, and the categories of exit and voice are conceived as mutually exclusive, which has been questioned in other works. Finally, these studies rely mainly on cross-sectional analyses that do not solve the problem of temporality, and they investigate reported behaviour rather than actual behaviours. In labour economics and management literature, the application of Hirschman’s model is very basic. The focus is on the trade-off between exit and voice, and little room is dedicated to theoretical debates. Overall, the accent is put on exit (turnover in firms) and voice is mainly seen as collectively expressed through unions. The main interest of these studies lies in their “considerable statistical sophistication” (Dowding et al., 2000: 486). In the same vein, marketing and psychologists have focused on the relation between consumers and producers. Again, the main focus is exit and the impact of the market competition on the choice to exit or not. Urban studies have also focused on exit (defined as the decision to move - Dowding et al., 2000). Their contribution is to have introduced 4 longitudinal approaches (data collected on both the intention and the realization). They are also the first to emphasize the richness of voice (differentiate between private and collective voice). Hirschman’s trilogy has been startlingly ignored by political scientists. It is even more surprising knowing that Hirschman himself applied his model to political phenomena in two of his chapters (however qualified by Barry as his weakest). One is an attempt to explain the failure of the dissident members of the Johnson administration to resign and denounce the Vietnam War due to ‘excessive loyalty’. The other is an application of his ideas to party competition in the USA, where he paved the way for May’s law of curvilinear disparity (1973). In a downsian model, activists discontented by their party’s moderate policies, having nowhere to go, would have two options. They can mobilize to push their party away from the centre, or become apathetic. Leaders have to find the optimal mix between electoral efficiency (centripetal tendencies) and keeping support from their activists (centrifugal tendencies). Political scientists haven’t completely forgotten Hirschman. Some work in comparative politics used his framework. According to Dowding et al. (2000), the use is rather fluid and loose, and concepts are used merely to give a name to processes. There is no rigorous test of models as it is the case in other fields. Some comparative studies focus on the role of state repression in the choice between voice and exit (Lee 1972; O’Donnell, 1986; Scott, 1986; Hirschman, 1993; Colomer, 2000; Pfaff & Kim, 2003; Gehlbach, 2006). Others are interested in the role of socio-economic (Ross, 1988), or institutional variables such as the type of regime (Clark, Golder & Golder, 2006) to explain the choice between modes of participation. Finally, others analyze the role of foreign aid, inequality, economic development, natural resources and authoritarianism on democratic transition (O’Donnell, 1986). There are extremely few applications of the model to party organizations, and they all focus on party elites and not on the party members. It is the case for Eubank et al. (1996), who look at the decline of the Italian Communism and the role of loyalty in the reform proposals. In the same vein, Salucci explores the breakup of the Democratic Left party (DS) in Italy in 2007 through direct interviews of the party leaders. Others have used the trilogy to study behaviours of parliamentarians (Kato, 1998) or party leaders in one-party hegemonic regimes (Langston, 2002). Only Weber (2009) uses the model to explain voting behaviour in cycles (‘second-order’ elections effects at the EP). The above review underlines that the model has proved fruitful in various domains but has never been thoroughly applied in political science. Startlingly, its more obvious application to party organizations has been neglected. However, we think it is a fertile ground to study (dis)satisfaction among party members, and their reactions to dissatisfaction, or the nature of intra-party participation. 5 Decline in quality: Dissatisfaction among party members Parties are not homogeneous entities and it seems inevitable that some events or leadership decisions will create dissatisfaction among membership. However, the literature on party membership often takes for granted that members are happy, and love and support their party (van Haute, 2009). Dissatisfaction is rarely investigated, if not completely ignored. In that sense, Hirschman’s premise is an interesting starting point. Exit, voice and loyalty are conceived as various reactions to a decline in quality of performance of an organization. The notion of decline in quality is rather vague. Few applications of Hirschman’s model discuss the concept; they tend to focus on the reactions to decline (EVLN) and to take the decline for granted without defining or measuring it. Most of them assume tangible and objective decline in quality. However, consumers will not react to decline in quality per se. Their reactions will rather be triggered by their own perception of decline in quality. Hirschman himself (1970: 48) suggests that there are differential evaluations of the decline in quality among consumers, depending on their criteria of evaluation (he distinguishes the gourmets and the gourmands). The perception of decline would be expressed by (dis)satisfaction with specific criteria of evaluation. It is what studies in labour economics do when they equate measure of quality to measure of job satisfaction. They operationalize the concept in multiple dimensions and indicators, such as the satisfaction towards leadership, nature of specific tasks, relation with co-workers, role of supervisors, personenvironment fit, promotion opportunities, compensations and benefits, etc. (Bateman & Organ, 1983; Mayes & Ganster, 1988). As regard party organizations, we are not interested in decline in quality of the performances of the party per se. We are interested in the perception of this decline in quality by party members, because this is what might trigger their reaction. Evidence shows that such perception of decline or dissatisfaction is present among party members. For example, among the French-speaking socialists (PS), 46% of the respondents think that the party has abandoned its principles, 20.5% think that party members do not have a say in the decision-making process, 8.7% think that the party does a bad job in power, and 5.5% are not satisfied with the leadership of the party. In the same vein, van Haute and Carty (2011) have shown that political parties host a lot of ‘misfit’ members, i.e. members who position themselves at odds with their party on a left-right scale. It is a clear case of personenvironment misfit, one of the dimensions of dissatisfaction. 6 Table 1. Party Members: Perceptions of Self & Party (%) Congruent / perfect fit Misfits N Canada CA PC Lib NDP BQ 44.3 29.7 32.3 24.2 41.7 7.5 20.7 17.4 25.0 15.7 961 Belgium VLD CD&V PS Ecolo 45.8 52.2 42.8 46.7 19.3 12.5 22.9 12.5 404 Total 39.8 16.5 6195 784 815 575 362 510 783 1001 So far, surveys provide only impressionist accounts for dissatisfaction. We suggest that surveys should include a systematic and coherent measure of membership satisfaction. One way to do this is to rely on indexes developed in labour economics to measure job satisfaction, such as the Job Descriptive Index (JDI), the Job in General Index or the Job Diagnostic Survey (JDS). Such an index could tap various facets of satisfaction: - Satisfaction with collective goals (overall project, ideological orientation of the party) Satisfaction with material benefits (promotions and pay) Satisfaction with interactions with co-workers (social interactions) Satisfaction towards the leadership Satisfaction with the functioning of the organization (role granted to members, rights & obligations) Analyzing the decline in quality of party membership via dissatisfaction would bring new light on intra-party life and dynamics. One interesting question raised in this respect is the origin of dissatisfaction. Barry (1974) argues that a decline in the quality of performance is not enough, and that the central point is the possibility of improvement, i.e. the belief that the organization can do better. However, Birch (1975) argues that the possibility of improvement is always present, and that the real question is rather why the quality becomes suddenly problematic. Applied to party organizations, the question would be why would certain party members become at some point dissatisfied with their membership? The literature provides hypotheses for the reasons to growing dissatisfaction (Birch, 1975; Bajoit, 1988). 7 Dissatisfaction can plant its roots in a relative decline in quality: a new contender appears on the market with a higher-quality product (or a better job offer), or an old rival improves its offer, which makes the organization’s own offer look less appealing. Here, it’s the comparison with the existing market that generates dissatisfaction. Party members would compare their current situation to their potential situation in other parties. Dowding et al. (2000) warns that this very much depends on the nature of the firm, and that competition would be less fierce between purposive organizations. However, it forces researches to take into account the context in which parties and party members play, and not study parties as isolated islands. Dissatisfaction can be related to an absolute decline in quality, i.e. diminishing performances of the organization. The organization would not be able to provide the same equilibrium between costs and benefits to its employees. Growing costs and diminishing benefits would trigger dissatisfaction. Clark, Golder & Golder (2006) provide examples for this kind of situation: a state introduces new taxes, devaluates its currency, or pass new rules about public schools. It can affect the equilibrium between costs and benefits for citizens, and generate dissatisfaction. The same reasoning can be applied to political parties. The party can face problems in maintaining the equilibrium between retributions to members and costs of membership. It can raise the fees, or not be able to provide the same upward mobility anymore (Bajoit, 1988: 337). It can reduce the fit between the member and its environment and increase the difference between the wants of the members and the perception of what’s available (Mayes & Ganster, 1988), and generate dissatisfaction. Finally, agenda setters or ‘agitators’ can initiate or facilitate the perception of decline among individuals. They provoke an aspiration for improvement. Responses to dissatisfaction As we have pointed, the existing surveys on party membership rely mainly on the theories of political participation. They provide data on reasons for joining or on the level of intra-party participation. It gives an idea of the intensity of participation (Whiteley & Seyd, 2002): the amount of time that members dedicate to party activities, their attendance to party meetings and congresses, etc. However, surveys do not provide information on the nature of intra-party participation. What do members actually do when they participate to a meeting? Do they attend silently? Are they intervening in debates? So far, surveys are missing this essential aspect of intra-party dynamics. Hirschman provides another new avenue for research with his model of the consequences of dissatisfaction in organizations. When facing a decline in quality, consumers can react in various ways. According to Hirschman, they can either decide to leave the organization (exit), or to stay and 8 try to improve the situation (voice). The choice between the two would be affected by the level of loyalty of individuals towards the organization. One cannot study responses to dissatisfaction without discussing first the status of loyalty in the model. The concept is highly ambiguous in Hirschman’s own work. Sometimes loyalty is depicted as an attitude (influencing the choice between voice and exit); at other times it is described as a form of behaviour (a distinctive response to dissatisfaction). This has been the source of continuous debates in the literature. Besides, it is a value-laden term, related to ideas such as constancy, fidelity, devotion, considerable attachment, sense of belonging, or strong affection (Graham & Keeley, 1992). We agree with Dowding et al. and suggest seeing loyalty as an independent psychological variable, an attitude linked to identification (Campbell et al., 1960) built on past investment (personal history and social capital, reinforced by social groups). This strong attachment or identification can be directed towards the product (brand loyalty) or the organization – or part of it (group or sub-group loyalty). Group membership becomes part of individual identities; party identification becomes part of selfidentity. Therefore, we do not treat it as a possible reaction to dissatisfaction, but as a factor influencing the choice between the possible reactions (see below). The range of possible reactions to dissatisfaction has also been debated heavily. Hirschman’s model presents a binary choice between voice and exit (or fight vs. flight). According to Barry, there is a first choice between exit and stay, and a second choice between voice and silence in both situations, broadening the model to 4 possibilities (exit & voice, exit & silence, stay & voice, stay & silence). Rusbult et al. (1988) propose to differentiate constructive and destructive reactions, which we think cannot apply to exit because exit already destroys the relationship with the organization. Dowding et al. (2000) add another nuance when they distinguish individual and collective reactions, which is crucial for purposive and collective organizations such as parties. To apply typologies of reactions to dissatisfaction to party organizations allows grasping dynamics in party life. It shifts the research away from the analysis of the intensity of intra-party participation, and brings it closer to the study of the nature of participation and the variety of intra-party behaviours. A first type of response to dissatisfaction would be to exit the organization, according to Barry’s revision of Hirschman’s model. Applied to political parties, the choice to exit is binary: 1. Exit & voice: the individual (or a sub-group) breaks the relationship and retreat from the authority in a vociferous manner. It is combined with attempts to convince others, with confrontation with the leaders, etc. Examples of individual type of vociferous exit are party 9 officials resigning in protest, or an ordinary member exiting a local meeting with angry comments, slamming the door. Vociferous collective exit can be associated to party scission, when a sub-group decide to leave the party. 2. Exit & silence: the individual (or a sub-group) breaks the relationship quietly. Kolarska & Aldrich (1980) emphasized that this reaction might have contradictory consequences, since the reason for exit may remain undetected for some time, the discontent will not spread and it will delay mass exit. Examples of individual quiet exit are party members who do not renew their membership, party officials who retire from politics. Collective exits are by definition more noticeable, and we find it difficult for it to be quiet. The choice to stay in the organization paves the way to a variety to reactions or forms of intra-party behaviours. We argue that stay can be associated with 4 different types of behaviour, along a voice/silence and constructive/destructive classification: Table 2. Typology of intra-party responses to dissatisfaction Voice Silence Constructive Stewardship Resignation Destructive Sabotage Neglect 1. Stewardship: the individual (or a sub-group) decides to voice dissatisfaction to improve the relationship and suppress discontent. Bajoit associates this behaviour to a mix of conviction and vigilance. In a party organization, stewards would for example make suggestions, develop argumentation, participate to the decision-making process, use principled dissent, etc. (Gorden 1988: 285). 2. Sabotage: the individual (or a sub-group) decides to use voice to destruct. To distinguish it clearly from stewardship, we have to look at the content of the behaviour, and not at the intention of the actor. Sabotage would therefore include complaining to other members, duplicitous behaviour, verbal aggression, bad-mouthing, etc. Laver (1976) associates collective voice to consumer associations; Spencer (1986), to unions. They both consider collective voice as channels of expressions, voice amplifiers, which would reduce (or delay) exit but could also lead to heating up if the organization does not correct the decline. In a political party, collective voice can be related to factions and factionalism (Close, 2011). 10 Voice can be expressed horizontally (among equals at the local level) or vertically (talking to superiors or party leaders), and expressed inside party channels or outside the party. 3. Resignation: the individual (or a sub-group) decides to endure and accept the situation passively until things improve. It entails tolerance, patience and faith (Graham & Keeley 194). In an organization, it translates into behaviours such as attentive listening, quiet support, unobtrusive compliance (self-censorship) and cooperation (Gorden 1988: 285) Gorden underlines that too much esprit de corps/teamness might have negative consequences for organizations. ‘Groupthink’ can favour cover-ups or loss of individual critical thinking. Hirschman stresses out the necessary balance between voice and silence in an organization. Resignation would moderate the effects of voice (stewardship or sabotage), but it should not be too strong for it would lead to degradation (Farrell, 1983). 4. Neglect: the individual (or a sub-group) decides to wait until things fall apart (Rusbult et al, 1983). In an organization, it translates into behaviours such as absenteeism, virtual withdrawal, calculated silence, or apathy. It can be summarized by considerations like “I just work here” (Gorden 1988: 285). These various reactions can succeed or precede each other in time (sequential), or be combined and co-occur (Laver, 1976: 469; Withey & Cooper, 1989). They are certainly not mutually exclusive (Dowding et al., 2000: 491). We do not claim that these types of behaviours are the only options in a party. For example, there are behaviours associated with satisfaction that could be investigated further: compliance, dependability, cooperation, etc. (Bateman & Organ, 1983). We argue that these are possible responses to a perception of decline in quality. The notion of perception is crucial because decline can go unnoticed, due to inattention, selective perception or total blindness (cult and diminished sense of individuality - Graham & Keeley: 194). If unnoticed, there is no dissatisfaction, and therefore no reaction to it. The stay is not associated to a conscious decision. Factors explaining the choice between alternative reactions In some cases, when dissatisfied, individuals have no choice between various options. Bajoit takes the example of some regimes with a high level of control. In these contexts, stay & voice is not an option and the only possible reactions are exile or stay & silence (Bajoit, 1988: 334). Apart from these extreme cases, individuals make a choice between various behaviours. The factors affecting the choice of individuals are a fascinating ground for new research. It would help to better understand the intra-party dynamics and the choices that party members make. It would shed light on the 11 dynamics that lead to membership renewal or exits, and add empirical flesh to hypotheses about membership decline. The literature emphasizes different factors that could affect the choice of individuals. These factors are related to the context (macro level), the type of organization (meso level), and the characteristics of the individual (micro level). Indeed, the choice of behaviour is the result of two forces: push and pull (Withey & Cooper, 1989). Macro level factors One major factor is emphasized in the literature as a factor diminishing the probability to stay when dissatisfied: the existence of attractive alternatives (Whitey & Cooper: 523-524). Bajoit stresses that if exit is easy, stay will less be considered. In other words, monopoly favours stay, and competition tends to favour defection. In the case of party organizations, multiparty systems would favour exit whereas dominant party systems tend to favour stay, because exit is difficult and protest inefficient or repressed. This hypothesis has been suggested to explain why we find more misfit members in the Canadian parties than in Belgian parties: the alternative options are more numerous in the Belgian case, and dissatisfied members would therefore find it easier to exit the party. Members who feel at odds with their party have more alternative options than in the Canadian context, where dissatisfied members do not have alternative options. It could explain why they decide to stay (van Haute & Carty, 2011). There would be less dissatisfied members in multiparty systems. Meso level factors The choice of individuals’ reactions to dissatisfaction is also influenced by the type of organization they belong to. Some characteristics of the organization can affect the decision to exit or stay: 1. The goal of the organization: Political or ideological organizations would favour stay, whereas firms or businesses would face more exits in case of dissatisfaction. 2. The accessibility: The openness of the organization to dialectic, and the existence of channels of communication (Gorden, 1988: 293) enhance the probability to stay. If dissatisfaction can be heard through formal, legitimate mechanisms (grievance procedures, etc. – Mayes & Ganster, 1988; Spencer, 1988), the probability of exit would be lower. However, the existence of channels of communication is not enough. Individuals must perceive the effectiveness of the existing voice mechanisms (Spencer, 1988) – see micro level factor below. 12 3. The fear of retaliation: The fear that intervention would make things worse (reprisals, repression, retaliation) favours exit over stay (Birch, 1975: 75). Some features of the organization affect the decision to voice dissatisfaction or remain silent: 1. The expected reaction of the leaders / responsiveness of the organization: An authoritarian leader or obedience-oriented organization will provoke stay & silence or exit & silence; a more understanding boss or participationist organization will provoke stay & voice. 2. The hierarchical structure of the organization: centralized organizations will favour silence, whereas decentralized organizations will favour voice. 3. The localization of expertise: if expertise is in the hand of the leadership as regard the cause of dissatisfaction, it favours silence over voice. 4. The possibility of social or geographical mobility: low mobility favours protest. In the case of party organizations, it would be very interesting to test the impact of the type of organization on the members’ behaviours, especially when they face dissatisfaction. It would give evidence to support the cartel thesis by empirically linking a specific type of party organization to specific reactions to dissatisfaction, among which exit. We could test if certain types of organizations, such as cartellized parties, favour exit over stay. We could thereby explain declining party membership figures. Micro level factors In Hirschman’s model, the individual’s choice between various types of behaviours is above all an economic decision, or a costs-benefits calculation (Whitey & Cooper, 1989: 523-524). Individuals would weights de benefits and costs of the alternatives (stay or exit): 1. The benefits from stay: individuals weight the potential value of improvement 2. The benefits from exit: individuals calculate the value of the best alternative (the direct gains from exit, but also the expected gains over time 3. The costs of stay: individuals take into account the costs of stay, such as the efforts required, the likelihood of punishment, or the possibility of improvement 4. The costs of exit: individuals weight the potential costs of exit, such as the direct switching costs (sanctions and costs of confrontation, loss of income or benefits, blocked opportunities), but also the indirect costs of exit such as sunk costs (loss of skill specificity, 13 loss of investment, emotional strain, loss of position and privileges/reputation, loss of social network and connections, loss of ease, sense of failure). The costs of exit are related to the cost of entry in the group: the higher the costs of entry in the group (ex.: closed groups such as cults), the higher the costs of exit. One can therefore expect that more discontent is needed before exit, but that the reaction will be more violent and quick. The costs of exit are also related to the embeddedness of the individual in the organization: the more embedded in the group (ex.: spouse in the party), the higher the costs of exit. In other words, people would stay only if the value of a given probability of a given improvement is higher than the value of the best alternative minus the costs of exit plus the cost of exercising voice. According to Barry (1974: 92), stay is “rarely an option that a rational person would choose”, especially staying to claim a general increase in quality (stewardship). The logic behind is the same as in the collective action problem: individual voice is not free, whereas the expected benefits are public and collective. The paradox is that people do stay & voice (Laver, 1976: 464). Therefore, voice will only be rational if people are seeking for individual benefits (selective improvement), such as selective material improvement, process improvement, or ideological improvement. However, Barry also recognizes that sometimes people want to exercise voice irrespective of the calculations. It’s a “consumer crusade”, where voice can be regarded as a form of life in some collectivity (collective improvement). The rational approach can be complemented with social psychological literature, which can explain the relationship between attitudes and behaviours. A first social psychological factor that can help to overcome the paradox is loyalty (expressive factor in Whiteley & Seyd’s model). Barry argues that loyalty is an ‘ad hoc equation filler’ and a post hoc explanation of why people decide to exit or not, logically redundant. Birch’s attack regards the nature of the concept. Hirschman argues that the higher the level of loyalty, the higher the probability to voice rather than exit. Birch contests that loyalty favours voice. He links loyalty to allegiance, fidelity or attachment, and therefore to someone who accepts the leaders’ decisions rather than someone who would criticize them constantly. According to Birch, “a critic is necessarily disloyal” (1975: 75). We agree with Birch as well as Laver (1976: 479) when he states that “what is clear is that Loyalty is associated with Stay”. Loyalty would explain why some people make the irrational decision to stay in an organization, even when this organization offers declining quality and unsatisfactory performances. According to Birch, strong loyalty diminishes the probability to exit, but also the probability to voice when staying in the organization. More specifically, a strong identification with the project (brand loyalty) makes individuals psychologically resistant to change, and blind to alternatives. They do not see attractive alternatives and think they have nowhere to exit. A strong identification with the organization (group 14 loyalty) increases the costs of exit. Both types of loyalty make it difficult to exit and explain individuals sometimes fail to act as utility maximizers, and why dissatisfied individuals can make to choice to stay in the organization. A second class of social psychological factors is linked to the expectations-values-norms model (Finkel, Muller & Opp, 1979), where behaviours are understood as the result of expected benefits and social norms. Expected benefits (likely success of the action) lie outside the rational choice model since it emphasizes the cognitive calculations guiding action. The expected benefits are relates to prior satisfaction (indicator that recovery is possible, probability of improvement) and the locus of control or sense of efficacy (Whitey & Cooper: 523-524; Dowding et al., 2000: 476). A third class of social psychological factors are personality traits and individual competences. The literature distinguishes optimistic and pessimistic traits. Optimists would have confidence in the organization, and therefore stay, whereas pessimists would exit (Laver, 1976). In the same way, individuals with critical analysis and innovative thinking would choose voice over silence, whereas individuals characterized by high levels of trust and patience would choose silence over voice. Finally, the nature of dissatisfaction affects the reaction. The higher the importance and the breadth of the problem, the higher the probability of voice over silence (Withey & Cooper, 1989: 523-525). The time horizon has also an impact on the reaction. If individuals face a long-term problem, they would tend to favour voice over silence. Conversely, a short-term problem has a higher probability to generate silence (Graham & Keeley 1988). Conclusion Literature on party membership focuses on the question of who joins parties and why. This paper has shown that it leads to major weaknesses in our capacity to understand the relationship between individuals and their organization. Consequently, it recommends to combine theories rooted in social psychology and studies of organizations rooted in labour economics and management. The paper uses Hirschman’s model on exit, voice, and loyalty to suggest new avenues for research on party organizations and party membership. A first avenue for research lies in the measuring and understanding of dissatisfaction among party membership. Parties are not homogeneous entities and one can assume the choices and decisions made do not always please the grassroots. However, we know very little about this phenomenon, its origins, its facets and its consequences for party organizations. The paper suggests ideas to measure (dis)satisfaction, as well as explanatory hypotheses to test. 15 A second avenue for research consists of investigating the nature of intra-party dynamics rather than the intensity of participation. We know that party members are not all active and participating. Whiteley & Seyd (1998) have shown that between 1990 and 1994, in the average month, “the mean number of hours worked in the case of Labour fell from 1.96 to 1.89, and the mean number of hours for the Conservatives from 1.44 to 1.40”. What we do not know is what kind of behaviour party members adopt when engaging in party activities. However, we argue that this is crucial if we want to understand intra-party dynamics and their consequences for party organizations. Thirdly, the paper suggests developing explanatory models of behavioural choices. Individuals face various options when dissatisfied with the party organization. We argue that research has to be performed so as to better grasp what triggers the individuals’ decision in favour of one form of behaviour above the others. This is crucial in order to understand why some members stay whereas others leave the party. It can provide empirical contributions to the theories of membership decline. Finally, the paper has shown that the existing literature does not allow tackling the question of intraparty processes and dynamics. This is mainly due to the method used so far to study party membership. Data has been predominantly collected via cross-sectional surveys. Previous research in other fields has shown that longitudinal (panel) surveys and experimental studies contribute in a more significant way to our knowledge of dynamics and processes. If we want to go beyond the traditional questions of who joins and why, we have to investigate the relation between members and their party. Relations are dynamic and necessitate monitoring how the relation evolves over time in order to understand the processes through which members decide to renew their membership or leave the party. 16 References Bajoit G. (1988) ‘Exit, Voice, Loyalty… and Apathy: Les réactions individuelles au mécontentement, Revue française de sociologie, 29/2: 325-345. Barry B. (1974) ‘Review Article: ‘Exit, Voice, and Loyalty’, British Journal of Political Science, 4/1 : 79107. Bateman T.S. & Organ D.W. (1983) ‘Job Satisfaction and the Good Soldier: The Relationship between Affect and Employee ‘Citizenship’, The Academy of Management Journal, 26/4: 587-595. Biemer P.P. et al. (2004) Measurement Errors in Surveys, Hoboken, Wiley. Birch A.H. (1975) ‘Economic Models in Political Science: The Case of ‘Exit, Voice, and Loyalty’’, British Journal of Political Science, 5/1: 69-82. Boroff K.E. & Lewin D. (1997) ‘Loylaty, Voice, and Intent to Exit a Union Firm: A Conceptual and Empirical Analysis’, Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 51/1: 50-63. Clark W.R. et al. (2006) ‘Power and Politics: Exit, Voice, and Loyalty Revisited’, paper presented at the 2006 Annual Meeting of the APSA, Philadelphia. Close C. (2011) ‘Le factionnalisme partisan: imbrication ou concurrence des loyautés?’, paper presented at the 4ème Congrès international des associations francophones de science politique, Brussels. Colomer J.M. (2000) ‘Exit, Voice, and Hostility in Cuba’, International Migration Review, 34/2: 423442. Dalton R.J. & Wattenberg M.P. (eds) (2000) Parties Without Partisans. Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies, Oxford, Oxford University Press. Dowding K. et al. (2000) ‘Exit, voice and loyalty: Analytic and empirical developments’, European Journal of Political Research, 37: 469-495. Downs A. (1957) An Economic Theory of Democracy, New York, Harper. Eubank W.L., Gangopadahay A. & Weinberg L.B. (1996) ‘Italian communism in crisis: A study in exit, voice and loyalty’, Party Politics 2: 55–75. Farrell D. (1983) ‘Exit, Voice, Loyalty, and Neglect as Responses to Job Dissatisfaction: A Multidimensional Scaling Study’, Academy of Management Journal, 26/4: 596-607. 17 Finkel S.E., Muller E.N. & Opp K.D. (1989) ‘Personal Influence, Collective Rationality, and Mass Political Action’, American Political Science Review, 83/3: 885-902. Gehlbach S. (2006) ‘A Formal Model of Exit and Voice’, Rationality and Society, 18/4: 395-418. Gorden W.I. (1988) ‘Range of Employee Voice’, Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, ¼: 283299. Graham J.W. & Keeley M. (1992) ‘Hirschman’s Loyalty Construct’, Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 5/3: 191-200. Heidar K. (2007) ‘What would be nice to know about party members in European democracies?’, Paper presented at the ECPR Joint Session of Workshops, Helsinki. Hirschman A. (1970) Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press. Hirschman A. (1993) ‘Exit, Voice, and the Fate of the German Democratic Republic: An Essay in Conceptual History’, World Politics, 45: 173–202. Katz R.S. & Mair P. (1995) ‘Changing Models of Party Organizations and Party Democracy: The Emergence of the Cartel Party’, Party Politics, 1/ 1: 5-28. Kato J. (1998) ‘When the party breaks up: Exit and voice among Japanese legislators’, American Political Science Review, 92: 857–870. Kolarska L. & Aldrich H. (1980) ‘Exit, Voice, and Silence: Consumers’ and Managers’ Responses to Organizational Decline’, Organization Studies, 1/1: 41-58. Langston J. (2002) ‘Breaking Out is Hard to Do: Exit, Voice, and Loyalty in Mexico’s One-Party Hegemonic Regime’, Latin American Politics and Society, 44/3: 61-88. Laver M. (1976) ‘Exit, Voice, and Loyalty’ Revisited: The Strategic Production and Consumption of Public and Private Goods, British Journal of Political Science, 6: 463-482. Lee W.-C. (1972) ‘Read my lips or watch my feet: The state and Chinese dissident intellectuals’, Daedalus, 101: 35–70. May J. (1973) ‘Opinion Structure of Political Parties: The Special Law of curvilinear Disparity’, Political Studies, 21: 135-151. 18 Mayes B.T. & Ganster D.C. (1988) ‘Exit and Voice: A Test of Hypotheses Based on Fight/Flight Responses to Job Stress’, Journal of Organizational Behavior, 9/3: 199-216. O’Donnell G. (1986) ‘On the fruitful convergence of Hirschman’s exit, voice and loyalty and shifting involvements: Reflections from the recent Argentine experience’. In: A. Foxley, M. McPherson & G. O’Donnell (eds), Development, Democracy and the Art of Trespassing: Essays in Honor of Albert Hirschman, Notre Dame, Notre Dame Press. Olson M. (1965) The logic of collective action: Public goods and the theory of groups, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press. Pfaff S. & Kim H. (2003) ‘Exit-Voice Dynamics in Collective Action: An Analysis of Emigration and Protest in the East German Revolution’, American Journal of Sociology, 109/2: 401-444. Reiter H.L. (2006) ‘The Study of Political Parties, 1906-2005: The View from the journals’, American Political Science Review, 100/4: 613-618. Ross M.H. (1988) ‘Political organization and political participation: Exit, voice and loyalty in preindustrial societies’, Comparative Politics, 21: 73–89. Rusbult C.E. & Zembrodt I.M. (1983) ‘Responses to Dissatisfaction in Romantic Involvements: A Multidimensional Scaling Analysis’, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 19: 274-293. Rusbult C.E. et al. (1988) ‘Impact of Exchange Variables on Exit, Voice, Loyalty, and Neglect: An Integrative Model of Responses to Declining Job Satisfaction’, The Academy of Management Journal, 31/3: 599-627. Salucci L. (2008) ‘Left No More: Exit, Voice and Loyalty in the Dissolution of a Party’, paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the APSA, Boston. Scott R.J. (1986) ‘Dismantling repressive systems: The abolition of slavery in Cuba as a case Study’. In: A. Foxley, M. McPherson & G. O’Donnell (eds), Development, democracy and the art of trespassing: Essays in honor of Albert Hirschman, Notre Dame, Notre Dame Press. Seyd P. & Whiteley P. (1992) Labour’s Grassroots. The Politics of Party Membership, Palgrave, Macmillan. Singh J. (1990) ‘Voice, Exit, and Negative Word-of-Mouth Behaviors: An Investigation Across Three Service Categories, Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, 18/1: 1-15. 19 Spencer D.G. (1986) ‘Employee Voice and Employee Retention’, The Academy of Management Journal,29/3: 488-502. Van Haute E. (2009) Adhérer à un parti. Aux sources de la participation politique, Brussels, Editions de l’Université de Bruxelles. Van Haute E. (2009) ‘Party Membership and Discontent’, paper presented at the 81st Canadian Political Science Annual Conference, Ottawa. Van Haute E. & Carty R.K. (2011) ‘ideological misfits: A distinctive class of party members’, Party Politics, forthcoming. Verba S., Nie N.H. & Kim J. (1978) Participation and political Equality: a seven-nation comparison, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Weber T. (2009) ‘Exit, Voice, and Cyclicality: A Micro-Logic of Voting Behaviour in European Parliament Elections’, paper presented at the 2009 EUSA Conference, Los Angeles. Whiteley P., Seyd P. & Richardson J. (1994) True Blues: The Politics of Conservative Party Membership, Oxford, Clarendon Press. Whiteley P. & Seyd P. (1996) ‘Rationality and Party Activism: Encompassing tests of Alternative Models of Political Participation’, European Journal of Political Research, 29/2: 215-234. Whiteley P. & Seyd P. (1998) ‘The dynamics of party activism in Britain: a spiral of demobilization?’ British Journal of Political Science, 28: 113-137. Whiteley P. & Seyd P. (2002) High Intensity Participation. The Dynamics of Party Activism in Britain, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press. Whitey M.J. & Cooper W.H. (1989) ‘Predicting Exit, Voice, Loyalty, and Neglect’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 34/4: 521-539. 20