Voyager Program

advertisement

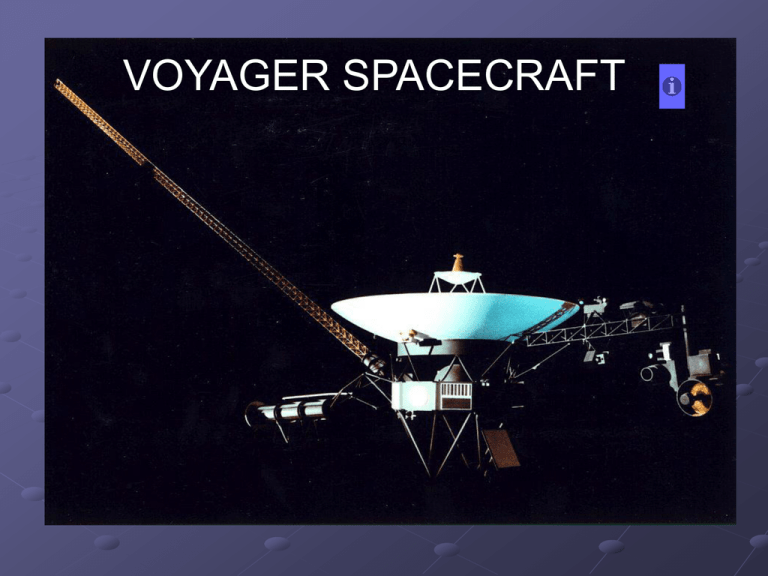

VOYAGER SPACECRAFT Voyager 2 launched on August 20, 1977, from Cape Canaveral, Florida aboard a Titan-Centaur rocket. On September 5, Voyager 1 launched, also from Cape Canaveral aboard a Titan-Centaur rocket. moons Photography of Jupiter began in January 1979, when images of the brightly banded planet already exceeded the best taken from Earth. Voyager 1 completed its Jupiter encounter in early April, after taking almost 19,000 pictures and many other scientific measurements. Voyager 2 picked up the baton in late April and its encounter continued into August. They took more than 33,000 pictures of Jupiter and its five major satellites. Jupiter’s Moon Callisto Jupiter’s Giant Red Spot Saturn as Photographed by Voyager 2 Saturn and three moons as viewed by Voyager 2 Moons Montage of Saturnian system: Dione front; Tethys & Minas right; Enceladus & Rhea left; Titan distant top Saturn Ring System. ( This is a false color image which provides contrast between the rings) Huge canyon system Saturn Moon Tethys. True-color (left) and false-color views of Uranus. Jan 17,1986. Range 5.7 million miles. Farewell shot of crescent Uranus as Voyager 2 departs. Jan. 25,1986. Range 600,000 miles Voyager 2 color composite image of the southern hemisphere of Uranus' satellite Miranda from 147,000 km. At 480 km diameter, Miranda is the smallest of Uranus' 5 major satellites. Even at this distance evidence of a complex geologic history can be seen. Planet Neptune as photographed by Voyager 2 One of the most important features revealed by Voyager in 1989 was a huge storm which was called the Great Dark Spot. It had the dimensions of the Earth and it was similar to the Great Red Spot of Jupiter. However, when observed by HST in 1994, it had disappeared. Neptune’s moon Triton from 25,000 miles. Depressions may be caused by melting and collapsing of icy surface High altitude cloud streaks in Neptune’s atmosphere •Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 were identical spacecraft and they were launched to explore the outer regions of our solar system. •Voyager 1 was launched in Sept. 1977 with the objective to make studies of Jupiter and Saturn, their satellites, and their magnetospheres as well as studies of the interplanetary medium. •Voyager 2 was launched in Aug. 1977 with the same objectives as Voyager 1, except that an option was designed into its trajectory, and ultimately exercised, that would allow it to proceed on to Uranus and Neptune to perform similar studies. •Voyager 1 arrived at Jupiter in March 1979 • Voyager 2 arrived at Jupiter in July 1979 •After photographing Jupiter, both spacecraft were directed on to Saturn with arrival times in Nov. 1980 (Voyager 1) and Aug. 1981 (Voyager 2). •Voyager 2 was then directed to the remaining gas giants , Uranus (Jan 1986) and Neptune (Aug.) 1989 •Data collected by Voyager 1 and 2 were not confined to the periods surrounding encounters with the outer gas giants, with the various fields and particles experiments and the ultraviolet spectrometer collecting data nearly continuously during the interplanetary cruise phases of the mission. Data collection continues as the renamed Voyager Interstellar Mission searches for the edge of the solar wind's influence (the heliopause) and exits the solar system. SATURN Saturn's atmosphere is almost entirely hydrogen and helium. Voyager 1 found that about 7 percent of the volume of Saturn's upper atmosphere is helium (compared with 11 percent of Jupiter's atmosphere), while almost all the rest is hydrogen. Since Saturn's internal helium abundance was expected to be the same as Jupiter's and the Sun's, the lower abundance of helium in the upper atmosphere may imply that the heavier helium may be slowly sinking through Saturn's hydrogen; that might explain the excess heat that Saturn radiates over energy it receives from the Sun. (Saturn is the only planet less dense than water. In the unlikely event that a lake could be found large enough, Saturn would float in it.) Winds blow at high speeds in Saturn. Near the equator, the Voyagers measured winds about 500 meters a second (1,100 miles an hour). The wind blows mostly in an easterly direction. Strongest winds are found near the equator, and velocity falls off uniformly at higher latitudes The rings of Saturn have puzzled astronomers ever since they were discovered by Galileo in 1610 using the first telescope. The puzzles have only increased since Voyagers 1 and 2 imaged the ring system extensively in 1980 and 1981. In addition to the images, several Voyager instruments observed occultations of the ring system with radial resolution as fine as 100 meters. The rings have been given letter names in the order of their discovery. The main rings are, working outward from the planet, known as C, B, and A. The Cassini Division is the largest gap in the rings and separates Rings B and A. In addition a number of fainter rings have been discovered more recently. The D Ring is exceedingly faint and closest to the planet. The F Ring is a narrow feature just outside the A Ring. Beyond that are two far fainter rings named G and E. The particles in Saturn's rings are composed primarily of water ice and range from microns to meters in size. The rings show a tremendous amount of structure on all scales; some of this structure is related to gravitational perturbations by Saturn's many moons, but much of it remains unexplained. The ring system extends hundreds of thousands of kilometers from the planet. In fact, Saturn and its rings would just fit in the distance between Earth and the Moon. NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft flew closely past distant Uranus, the seventh planet from the Sun, in January 1986. At its closest, the spacecraft came within 81,500 kilometers (50,600 miles) of Uranus's cloudtops on Jan. 24, 1986. Voyager 2 radioed thousands of images and voluminous amounts of other scientific data on the planet, its moons, rings, atmosphere, interior and the magnetic environment surrounding Uranus. Voyager 2's images of the five largest moons around Uranus revealed complex surfaces indicative of varying geologic pasts. The cameras also detected 10 previously unseen moons. Several instruments studied the ring system, uncovering the fine detail of the previously known rings and two newly detected rings. Voyager data showed that the planet's rate of rotation is 17 hours, 14 minutes. The spacecraft also found a Uranian magnetic field that is both large and unusual. In addition, the temperature of the equatorial region, which receives less sunlight over a Uranian year, is nevertheless about the same as that at the poles. In the summer of 1989, NASA's Voyager 2 became the first spacecraft to observe the planet Neptune, its final planetary target. Passing about 4,950 kilometers (3,000 miles) above Neptune's north pole, Voyager 2 made its closest approach to any planet since leaving Earth 12 years ago. Five hours later, Voyager 2 passed about 40,000 kilometers (25,000 miles) from Neptune's largest moon, Triton, the last solid body the spacecraft will have an opportunity to study. Neptune is one of the class of planets -- all of them beyond the asteroid belt -- known as gas giants; the others in this class are Jupiter, Saturn and Uranus. These planets are about 4 to 12 times greater in diameter than Earth. They have no solid surfaces but possess massive atmospheres that contain substantial amounts of hydrogen and helium with traces of other gases. How big is our solar system? If you answered that it ends with Pluto's orbit (an average of 5,913,520,000 kilometers or 3,647,200,000 miles from the sun), you're in for a surprise! The powerof our sun actually extends at least twice that far. Our solar system is more than just the spacebetween the planets. The solar wind from our sun forms a sort of bubble that surrounds the nineplanets and goes beyond them. Scientists call the volume inside the bubble the heliosphere. Theymeasure the size of our solar system as the distance to the edge of the bubble. Bow Shock Heliopause Termination Shock The outer boundary is where the solar wind stops (heliopause). Scientists believe the heliopause is 20 to 22 billion kilometers (12 billion to 14 billion miles) from the sun. That is the edge of interstellar space (where the other stars are). The two Voyager spacecraft, launched way back in 1977, will probably be the first human-made objects to approach the heliopause. Before they cross into interstellar space, though, the two craft will pass through an area called the "termination shock." At that point, the solar wind should drop from more than 1,500,000 kilometers (nearly 1,000,000 miles) per hour to a very breezy 400,000 kilometers (250,000 miles) per hour. VOYAGER THIRTY YEAR PLAN The spacecraft are continuing to return data about interplanetary space and some of our stellar neighbours near the edges of the Milky Way. As the Voyagers cruise gracefully in the solar wind, their fields, particles and waves instruments are studying the space around them. In May 1993, scientists concluded that the plasma wave experiment was picking up radio emissions that originate at the heliopause -the outer edge of our solar system. The heliopause is the outermost boundary of the solar wind, where the interstellar medium restricts the outward flow of the solar wind and confines it within a magnetic bubble called the heliosphere. The solar wind is made up of electrically charged atomic particles, composed primarily of ionized hydrogen, that stream outward from the Sun. Exactly where the heliopause is has been one of the great unanswered questions in space physics. By studying the radio emissions, scientists now theorise the heliopause exists some 90 to 120 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun. (One AU is equal to 150 million kilometres (93 million miles), or the distance from the Earth to the Sun. The Voyagers have also become space-based ultraviolet observatories and their unique location in the universe gives astronomers the best vantage point they have ever had for looking at celestial objects that emit ultraviolet radiation. The cameras on the spacecraft have been turned off and the ultraviolet instrument is the only experiment on the scan platform that is still functioning. Voyager scientists expect to continue to receive data from the ultraviolet spectrometers at least until the year 2000. At that time, there not be enough electrical power for the heaters to keep the ultraviolet instrument warm enough to operate. Yet there are several other fields and particle instruments that can continue to send back data as long as the spacecraft stay alive. They include: the cosmic ray subsystem, the low-energy charge particle instrument, the magnetometer, the plasma subsystem, the plasma wave subsystem and the planetary radio astronomy instrument. Barring any catastrophic events, JPL should be able to retrieve this information for at least the next 20 and perhaps even the next 30 years.