CLASSIFICATION OF CHILDREN'S LITERATURE

advertisement

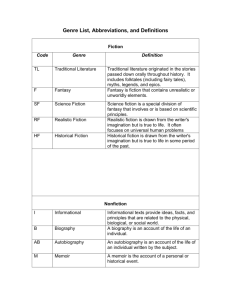

CLASSIFICATION OF CHILDREN’S LITERATURE 1. Traditional Literature • Refers to those that have been handed down from generation to generation by word of mouth before the invention of printing • They are a product of a race (e.g., the Teutonic or the Malay) and their features usually identify the people who put them together. • The body of traditional literature is sometimes referred to as folk literature. • The most common types are: Fairy tales Folktales Parables Fables Myths Riddles Catches Jingles, and Folk songs • Pourquoi stories tell why the sky is high or why the sea is salt or why the pineapple has a hundred eyes. ▫ “Pourquoi” is a french term meaning why. ▫ legends talk of the first banana, the first bamboo, or the first lanzon fruit. ▫ they explain the beginning of certain objects 2. Poetry • is not exactly the type of literature that most people get readily excited about. That is sad because, as children our first acquaintance with children’s literature was generally made through the little rhyming songs and jingles that we loved to repeat as we went about motions songs and choral recitations. Who has not sung “Little Sally Water,” “The Itsy-Bitsy Spider,” or “PenPen, Leron-Leron Sinta”? Those were our first poems! • Then you were taught “The Owl” and “All Things Bright and Beautiful.” Some of us were lucky to get introduced to the socalled Mother Goose Rhymes. They are nursery rhymes put together by Charles Perrault, a Frenchman who also wrote down the most popular Cinderella variant. When his collection was published, the book featured on its cover a picture of a big goose wearing “motherly” clothes and surrounded by listening young animals and children. Mother Goose introduced us to Mary and her lost lamb, Little Jack Horner, and “Twinkle, twinkle little star.” • The way you took to reciting and memorizing nursery rhymes in your childhood is similar to the way a two-year-old today would readily sing or recite the latest jingle. • Children also respond to simple lyrics that describe a familiar flower, the experience of hearing the rain on the roof, the aroma wafting from the kitchen when Nanay cooks ginataan, and the feeling one gets when Tatay comes home and being lost in his embrace. • There are nonsense poems that make children giggle, like the rhyme “Monumento/Konting bato,/ konting semento/Monumento.” When they are a little older, children are fascinated by the measured limericks, funny and witty verses that follow the aabba scheme, and its distinctive rhythm. For example: There once was a lady from Niger Who smiled as she rode on a tiger; They came back from the ride With the lady inside And the smile on the face of the tiger - a a b b a • There’s another that has a bit of sophistication in it: There was a young lady named Bright Whose steed was far faster than light. She went out one day In a relative way And returned on the previous night. • Edward Lear is the most well-known of the writers of limericks. In the centennial of his birth a few years ago, England released several stamps featuring his famous lines and drawings. • Other poems are narrative in mode rather than descriptive. They are easier to read, the narrative being an easier discourse for any type of reader to deal with. Your own or your parents’ recollection of narrative poems would probably include “Evangeline, A Tale of Acadie” and “Hiawatha,” both by Henry W. Longfellow, and Florante at Laura by Francisco Balagtas. For younger children, there’s “Winken, Blinken and Nod” and “ The Duel” by Eugene Field. Also, most of you probably still sing “Apat na Pulubi” to your children or the children of your other relatives. • Didactive poems are the openly “preachy” ones that we rarely see nowadays. Didactic mean “teaching”. An example of this kind of poem is “A Psalm of Life” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. It begins with: Tell me not in mournful numbers Life is but an empty dream For the soul is dead that slumbers And things are not what they seem. 3. Informational Books • Are those that allow young readers to accumulate as much factual knowledge as they might be interested in. • The selections include the very basic informational books such as alphabet book, numeracy books, and concept books, including those that introduce children to shapes and colors, and how-to-do-it books that teach them how to make paper boats or how to assemble a toy or how to bake angel cake. • The most common are the content area books, i.e., books that are read for the different subject areas: history, mathematics, science, social studies, health, etc. • Informational books on science concepts for early graders may be presented in the form of stories, as in Jose Aruego and Arianne Dewey’s We Hide, You Seek (camouflage), Adarna’s Munting Patak-Ulan (the concepts of evaporation and condensation), and Si Duglit, ang Dugong Makulit (circulation of the blood) by pediatrician-writer Luis P. Garmaitan. • Informational books would also include first dictionaries, encyclopedias, and atlases. 4. Biography/Autobiography • There are times when the biography and its related types are classified with informational books. The latter focuses on things, places, and concepts while the former targets personalities. • A story of one’s life written by oneself, as you know, is called an autobiography. • No Filipino writer of note has written An autobiography yet except Bienvenido Santos who gathered the letters he had sent his friends in his lifetime. From these, his life emerges, to be put together by the reader. • A biography may be a straight biography, a fictionalized biography, or biographical fiction. • A straight biography takes pains to share only documented facts about a particular individual. In style, it resembles history textbooks. • May Hill Arbuthnot, the expert on children and books, differentiates the two other sub-types of biography (Zena Sutherland, 1991) Fictionalized biographies are also based on research, but known facts are often presented in dramatic episodes complete with conversation. Biographical function, there are more authorial liberties taken, especially in the inclusion of (several) imaginary characters. • An example of straight biography would be the Tahanan series on Filipino heroes, including Jose Rizal and his mother, Teodora Alonzo, Andres Bonifacio, Apolinario Mabini, Emilio Aguinaldo, and Gabriela Silang. 5. Fiction • Fiction for children ranges from growing up stories to historical fiction; from mysteries to science fiction; from adventure stories to romance and fantasy; and that special classification that falls under the heading, animal stories. • Growing-up stories, as the name suggests, have themes that are close to the heart of the growing reader (based on the research which Diaz de Rivera conducted last 1988). The study yielded three most identified themes. The search for identity is first. Examples stories with this theme are Polly Cameron’s The Cat Who Thought He Was a Tiger, Elizabeth Guilfoile’s Nobody Listens to Andrew, and The Story about Ferdinand by Munro Leaf. • The warmth of family and home is another favorite theme, as evidenced by their choice of Breakfast with Father by Ron Roy, Make Way for Ducklings by Robert McCloskey, Millions of Cats by Wanda Gag, and Sylvester and the Magic Pebble by William Steig. • Friendship and the community spirit is a strong third in the roster of favorite themes. This is evident in the titles cited, such as Mirra Ginsburg’s Mushroom in the Rain, a retelling of Stone Soup by Marcia Brown, and The Biggest Bear by Lynd Ward. • It was found that they also like the theme of going away and coming back to a welcoming home. The journey motif enables young readers to take vicarious trips to new places, and meet new friends in the process. But they wish the young hero/es to always come home in the end. Typical of these stories are Little Ducklings Went Wandering and Where the Wild Things Are by the great Maurice Sendak. • Note that in these stories, other types of fiction may be identified, like adventure stories, mysteries and fantasy, and animal stories, although they deserve a section of their own. • Historical fiction is a field that is richly tapped in other shores but only timidly tried by local writers. The only Filipino titles that come to mind are Makisig, Boy Hero of Mactan by Gemma Cruz and Kangkong 1869 by Ceres Albarado. • A historical fictionist picks out a character, whether imaginative or actual, and situates the life of this character against the background of a historical event. In Cruz’s story, it was the Lapulapu-Magellan encounter. The Alabado novel is set in Kangkong, one of several places where the Cry of Balintawak is said to have taken place. • Animal stories are a subtype of fiction but they deserve a special discussion. • There are three types of animal stories: ▫ stories that present animals as they are ▫ stories that depict talking animals and ▫ those that show animals as people