Berne Union Working Paper No. 4

advertisement

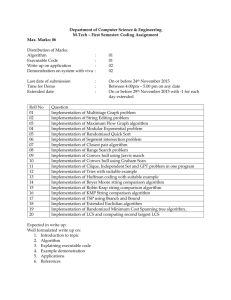

Berne Union Working Paper No. 4 International Trade, Risk and the Role of Banks Abstract International trade exposes exporters and importers to substantial risks. To mitigate these risks, firms can buy special trade finance products from banks. This paper explores when firms use these products. We find that letters of credit and documentary collections cover about 10 percent of U.S. exports and are preferred for larger transactions, indicating substantial fixed costs. Letters of credit are employed the most for exports to countries with intermediate contract enforcement. Compared to documentary collections, they are used for riskier destinations. We provide a model that rationalizes these empirical findings and discuss implications. Friederike Niepmann Federal Reserve Board friederike.niepmann@frb.gov Tim Schmidt-Eisenlohr Federal Reserve Board tim.schmidt-eisenlohr@frb.gov Berne Union Working Paper Series November 2015 The Berne Union is the international organization and community for the global export credit and investment insurance industry. This Working Paper Series aims to share new findings in the field of export credit insurance and international trade. The papers carry the names of the authors and should be cited accordingly. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in these papers are entirely those of the authors and cannot necessarily be attributed to the Berne Union or members of the Berne Union, nor should they be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System or of any other person associated with the Federal Reserve System. An electronic version of the papers may be downloaded from the Berne Union website: http://www.berneunion.org/about-the-berne-union/ Berne Union Working Paper No. 4 Introduction Trading across borders exposes firms to substantial risks. Exporters can mitigate these risks by buying trade finance products from banks, most importantly, letters of credit (LCs) and documentary collections (DCs). This Berne Union Working Paper summarizes our research on when firms use these products based on new data from the SWIFT Institute and the Federal Reserve Board.1 Forms of payment in International Trade Firms typically choose between four ways to organize payments in international trade: LCs, DCs, open account and cash-in-advance. The former two options always involve banks and are at the center of our analysis. The latter two types do not necessarily involve banks and are explained briefly at the end of this overview. How an LC works: The importer initiates the transaction by having its bank issue a letter of credit to the exporter. The LC guarantees that the issuing bank will pay the agreed contract amount after the exporter proves that it delivered the goods by providing a set of documents. To cover the risk that the issuing bank will not pay, an exporter may have a bank in its own country confirm the letter of credit, in which case the confirming bank agrees to pay the exporter if the issuing bank defaults. LCs typically have relatively short tenors. According to the ICC Trade Register, the average maturity of a confirmed LC is 70 days, while the average maturity of an importer LC is about 80 days.2 1 The SWIFT Institute is an entity set up by SWIFT that, among others, funds research and provides access to data derived from the SWIFT messaging system. For details on the SWIFT data and the Federal Reserve data please look at the full working paper Niepmann and Schmidt-Eisenlohr (2013). 2 See ICC (2013). 1 Berne Union Working Paper No. 4 Figure 1: How an LC works Source: Own illustration. How a DC works: A DC does not involve payment guarantees. Instead, the exporter's bank forwards ownership documents to the importer's bank; the documents, which transfer the legal ownership of the traded goods to the importer, are handed to the importer only upon payment for the goods. Figure 2: How a DC works Source: Own illustration. Alternatives to LCs and DCs: Firms can also decide to trade without an LC or DC and agree on pre-delivery payment (cash-in-advance) or post-delivery payment (open account). Open account can be combined with a trade credit insurance, which transfers the risk of counter- 2 Berne Union Working Paper No. 4 party default to an insurance company.3 In addition firms may obtain support from public export credit agencies (ECAs), in particular for transactions with high-risk destinations and for exports related to large long-term investments like infrastructure. ECAs may provide trade credit insurance when private firms are unwilling to provide coverage and may offer working capital facilities.4 Each payment form implies a different allocation of the risks and the financial costs inherent in the trade between the exporter and the importer. The following table summarizes the differences between the four choices: Table 1: Trade-offs between payment forms Exporter Importer Open Account Financing Risk X X — — Cash-in-advance Financing Risk — — X X Letter of Credit Financing Risk X — X — Documentary Collection Financing Risk X X X — Source: Own illustration. Under open account, the exporter is exposed to the risk that the importer does not pay. In addition, the exporter needs to finance the working capital for production and shipment until the payment from the importer is received. Cash-in-advance is the reverse case. The importer pays first and, therefore, bears the risk that the exporter does not deliver. Furthermore, the importer needs to finance the advance payment since revenues are realized only later. LCs almost entirely eliminate the risk of the transaction because banks monitor the firms and guarantee the payment. These instruments are quite costly because the issuing bank in the importing country and the confirming bank (if applicable) in the exporting country need to be compensated both for administrative costs as well as the risk they take on.5 With DCs the importer’s payment is not guaranteed by the banks, so some significant risk remains with the exporter. This makes DCs cheaper than LCs. Why these choices matter: Firms' payment choices are central for international economic activity. The availability of trade finance products and their costs directly impact the profitability of trade transactions and, therefore, firms' export behavior. Because banks in the source and the destination country collaborate to provide these services, their availability and costs depend on conditions both at home and abroad. This implies, for example, that a country with a perfectly sound financial sector may see a drop in imports 3 Trade credit insurance typically covers the whole turnover of an exporter. However, there is also the option to cover specific (single) supplier risks. 4 They also confirm LCs, especially to high-risk destinations. 5 In the table, for illustrative purposes, we assume that LCs have no risk. Even with a confirmed LC there is of course some residual risk. It is, however, quite small compared to the risk involved in the alternative payment forms. 3 Berne Union Working Paper No. 4 and exports when the trading partner’s economy experiences a financial crisis, due to changes in the availability or costs of trade finance there. Such concerns made policy makers and researchers around the world pay special attention to banks’ role in international trade during and after the 2008/2009 financial crisis. There were discussions around a perceived gap in the provision of trade finance by the private sector that triggered policy responses. For example, while many development banks had trade finance programs before the crisis, the support was ramped up substantially after 2008, especially the public confirmation of LCs.6 Moreover, the risk weights on LCs originally proposed by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision in 2010 were brought down over concerns that the new rules on capital and leverage would make trade finance too costly and harm trade.7 Stylized facts and Main findings Stylized Fact I: Bank Trade Finance covers about 14 percent of world-wide trade.8 By value of exports, LCs were used in 2012 for 8.8 percent of all U.S. export transactions, while DCs were employed for 1.2 percent. World-wide, LCs (DCs) backed about $2.3 trillion ($310 billion) of international trade, corresponding to 12.5 percent (1.7 percent) of world trade in goods. These numbers are far below the 30-40 percent of bank intermediated trade found in IMF surveys. Part of this discrepancy may be driven by the fact that there is no commonly accepted definition of trade finance. Hence, survey respondents might have included additional trade finance products in their estimates. These differences show the importance of getting access to accurate and reliable data like that provided by the SWIFT Institute as well as the need for clearly distinguishing between trade finance products in empirical studies.9 6 In the midst of the crisis, the G20 committed to extending the public support for trade finance by $250 billion, worried that firms would stop exporting without bank guarantees. The International Finance Organization, which is a part of the World Bank Group, now conducts a $5 billion program that mostly confirms LCs; see IFC (2012). 7 Specifically, trade finance is an off-balance sheet item that will receive a higher risk weight under the 2010 international agreement known as Basel III, produced by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision; and trade finance will also weigh on the Basel III leverage ratio. 8 This and the following numbers are based on calculations by the authors with data provided by the SWIFT Institute. SWIFT captures about 90% of total world letter of credit bank to bank flows. Compared to other sources, the SWIFT messages seem to measure overall LC-based trade extremely well. Ahn (2013), e.g., employs customs data from Colombia and Chile that cover all imports to these countries. He finds that Colombia and Chile use LCs for 5 and 10 percent of their imports, respectively. In comparison, the SWIFT data imply LC shares of 4.88 and 9.9 percent for these two countries, respectively. 9 For details on the IMF survey, see IMF (2009). 4 Berne Union Working Paper No. 4 Stylized Fact II: Bank Trade Finance use is very heterogeneous across countries. The use of LCs and DCs varies considerably by export market. Across destinations, the share of U.S. sales that are settled with LCs varies between zero and 90 percent in the SWIFT data; for DCs, usage lies between zero and 10 percent. Figure 3: Top 10 LC and DC destinations of U.S. exports Source: Own calculations. Figure 3 shows the use of LCs and DCs in U.S. exports to selected countries. Each destination’s LC (DC) intensity shown in the chart is calculated as the ratio of LC (DC) flows over total U.S. merchandise exports to the respective country. On the left are the 10 countries with the highest LC intensity. On the right are the 10 countries with the highest DC intensity. Stylized fact III: The trade finance business is highly concentrated. Data from FFIEC 009 reports collected by the Federal Reserve show that the trade finance business is highly concentrated, more than the US banking industry overall. In the data, we 5 Berne Union Working Paper No. 4 observe the claims that are related to trade finance of US banks against foreign counterparties by bank and country.10 In 2012, the top five banks accounted for 92 percent of all trade finance claims. On average, these banks served 70 destinations. The five next biggest trade finance banks each served only about 20 destinations and accounted for 7.5 percent of the market. The majority of FFIEC 009 reporters do not have any trade finance claims: only 18 out of 51 reporting banks. Figure 4: Distribution of claims and number of destinations in 2012 q2 Source: Own calculations. Empirical finding I & II: Intermediate risk countries use LCs the most; DCs largely increases with the destination's rule of law. The variation illustrated in Figure 3 is systematically related to factors associated with firms' optimal choice of payment arrangement. In particular, the use of LCs and DCs depends on the extent to which contracts can be enforced in the destination country. This should be expected since the main purpose of LCs and DCs is to reduce the risk of international trade transactions. Perhaps surprisingly, LCs are used the most for exports to countries with an intermediate level of quality in their legal institution and much less for the most risky destinations. At the same time, firms’ use of DCs increases in the quality of legal institutions in the destination country. These two results are illustrated in Figure 5 that plots predicted use of LCs and DCs against rule of law based on regression results in our paper. 10 These claims reflect mostly letter-of-credit transaction related to US exporting but may also include other trade finance instruments. For details on the data see Niepmann and Schmidt-Eisenlohr (2013). 6 Berne Union Working Paper No. 4 Figure 5: LC and DC use and destination rule of law Source: Own results. While maybe puzzling at first, these findings can be understood in a simple model of payment choice. The basic intuition for the result on LCs is that the value of risk mitigation through bank intermediation to the firm is offset to some degree by the cost of this financial service. Because banks can reduce but cannot eliminate the risk of a trade transaction, the fees they charge rise with the remaining risk they take on. For the riskiest destination countries, bank fees are so high that exporters prefer cash-in-advance. In that case, the importer pays before the exporter produces, through which payment risk can be entirely eliminated. Similarly, LCs are not used for low-risk destinations; for those transactions, the exporter prefers to save on bank fees and bear the payment risk. The fact that the use of DCs increases in the quality of legal institutions in the destination country can also be explained by our model. Intuitively, DCs reduce payment risk by less than LCs and therefore tend to be used for safer destinations. Figure 6 further helps clarify the mechanisms that generate the two results. 7 Berne Union Working Paper No. 4 Figure 6: Profitability of different payment forms Source: Own results. Figure 6 plots the profitability of the different payment forms against destination country contract enforcement (λ*). In the figure, risk decreases from left to right. When the importer pays in advance (CIA), profits are independent of destination country risk as pre-payment precludes default by the importer. Under open account (OA), destination country risk is central as the key concern is that the importer does not pay. LCs reduce this risk but the fees charged by the bank increase when risk rises. Consequently, profits with LCs fall with destination country risk but by less than profits with an open account. DCs also reduce the risk of non-payment but by less than LCs. At the same time, firms have to pay lower fees, which increase less quickly in destination country risk. The slope of the DCs profit line is therefore steeper than the line for LCs but flatter than the line for open account. This generates the following ordering: the riskiest destinations are, all else equal, served through cash-in advance. For intermediate risk countries, exporters mostly demand LCs. For countries of moderate risk, firms trade using DCs. Finally, trade with the least risky destinations is settled on an open account.11 This can also be seen in figure 7 that shows a simulation of the model. It depicts the shares of the four payment forms in total transactions for different levels of destination country contract enforcement (λ*). Again, LCs are used the most in intermediate risk destinations. 11 Of course, there are other factors at the firm and country level that affect the payment choice. Hence, in the data, typically all contracts can be observed for all destinations to some extent. The point to be taken away is that some contracts are more or less likely used if the country risk is low, high or intermediate. 8 Berne Union Working Paper No. 4 For very risky destinations, CIA dominates. One effect of ECA programs may be to shift the cutoff λ1. By supporting LC confirmations by banks, they can affect the cost of LCs relative to CIA and may thereby induce more firms to choose LCs over CIA. Figure 7: Simulated shares of the four payment forms Source: Own results. Empirical finding III: On average, DCs are used for intermediate size transactions and LCs are used for largest transactions. Finally, we document that the average size of trade transactions differs by type of payment contract. 9 Berne Union Working Paper No. 4 Figure 8: Average size of transactions and payment choices Source: Own results. Figure 8 shows the kernel densities of average transactions sizes by country of LCs, DCs and other payment forms. It is easy to see that LCs tend to have the largest average transactions sizes, followed by DCs and other transactions. The average value of letter-of-credit transactions is $716.2 thousand, followed by DCs with an average of $138.7 thousand. Transactions that do not rely on bank intermediation (cash-in-advance and open account) are on average much smaller ($39.2 thousand). These findings are in line with the theory in which LCs and DCs require the payment of fixed fees that cover the bank's costs for document handling and screening. LCs and DCs are more attractive for firms when shipments are large since the fee then is a smaller percentage of the total transaction value. The large differences in transactions sizes provide evidence for the existence of substantial fixed costs in the provision and use of trade finance products. Conclusions LCs and DCs are important instruments offered to firms by financial institutions. As our data show, together they cover about 14 percent of world merchandise trade. Understanding firms’ payment choices and the trade finance business more generally is relevant for policy 10 Berne Union Working Paper No. 4 makers and practitioners. A clear picture where and how much firms rely on bank trade finance products can help policy makers decide on the need for and the extent of public provision of trade finance. At the same time, firms’ payment choices and their responses to changes in financial conditions are important for understanding export and import behavior over the business cycle. At a more micro-level, the provided insights can be useful for providers of trade credit insurance (TCI) as LCs and DCs represent alternative ways to manage risk in international trade and should probably be seen as the closest substitutes for TCI. In the future, an effort should be made to combine data from Berne Union and SWIFT to study the TCI, LC and DC businesses jointly. This would allow to analyze in which cases these products represent substitutes, when they are more like complements and how they differ in their response to economic events. References Ahn, JaeBin, “Understanding Trade Finance: Theory and Evidence from Transaction-level Data,” May 2014. International Monetary Fund, mimeo. ICC, “Rethinking Trade Finance 2009: An ICC Global Survey,” ICC Banking Commission Market Intelligence Report, International Chamber of Commerce 2009. IFC, “Global Trade Finance Program Brochure,” International Finance Corporation January 2012. IMF, “Survey Among Banks Assessing Current Trade Finance Environment,” IMF-BAFT Trade Finance Survey, International Monetary Fund 2009. Niepmann, Friederike and Tim Schmidt-Eisenlohr, “International Trade, Risk, and the Role of Banks,” Staff Reports 633, Federal Reserve Bank of New York 2013. 11