Art History _Dada to Pop_lecture #2_blog notes

advertisement

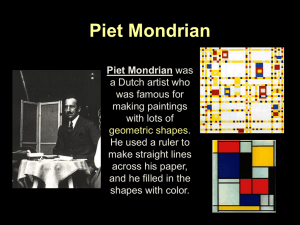

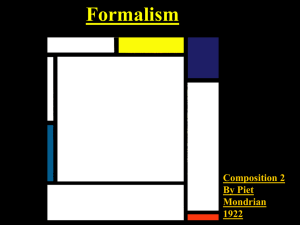

Art History: Dada to Pop 1915-1956 (AHIS 216-Winter) Thursdays, 2 pm to 5 pm Instructor, Danielle Hogan Email: hogan_danielle @shaw.ca New Objectivity The New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) emerged as a style in Germany in the 1920s as a challenge to Expressionism. As its name suggests, it offered a return to unsentimental reality and a focus on the objective world, as opposed to the more abstract, romantic, or idealistic tendencies of Expressionism. The style is most often associated with portraiture, and its leading practitioners included Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, and George Grosz. Their mercilessly naturalistic depictions, sometimes reminiscent of the meticulous processes of the Old Masters, frequently portrayed Weimar society in a caustically satirical manner. Max Beckmann Self Portrait with ta Cigarette, 1923 Max Beckmann Self Portrait 1916-17 Otto Dix The Mediterranean Sailor, 1923 Otto Dix Portrait of Mrs. Dix 1924 Otto Dix Dr. Mayer-Hermann Berlin 1926 George Grosz The Poet Max Herrmann-Neisse 1927 Bauhaus The Bauhaus, Dessau The Bauhaus looked to unify art, craft and technology Key Ideas ~The motivations behind the creation of the Bauhaus lay in the 19th century, in anxieties about the soullessness of manufacturing and its products, and in fears about art's loss of purpose in society. Creativity and manufacturing were drifting apart, and the Bauhaus aimed to unite them once again, rejuvenating design for everyday life. ~Although the Bauhaus abandoned much of the ethos of the old academic tradition of fine art education, it maintained a stress on intellectual and theoretical pursuits, and linked these to an emphasis on practical skills, crafts and techniques that was more reminiscent of the medieval guild system. Fine art and craft were brought together with the goal of problem solving for a modern industrial society. In so doing, the Bauhaus effectively leveled the old hierarchy of the arts, placing crafts on par with fine arts such as sculpture and painting, and paving the way for many of the ideas that have inspired artists in the late 20th century. ~The stress on experiment and problem solving at the Bauhaus has proved enormously influential for the approaches to education in the arts. It has led to the 'fine arts' being rethought as the 'visual arts', and art considered less as an adjunct of the humanities, like literature or history, and more as a kind of research science. Joseph Albers teaching at the Bauhaus Legacy of the Bauhaus The Bauhaus influence travelled along with its faculty. Gropius went on to teach at the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University, Mies van der Rohe became Director of the College of Architecture, Planning and Design, at the Illinois Institute of Technology, Josef Albers began to teach at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy formed what became the Institute of Design in Chicago, and Max Bill, a former Bauhaus student, opened the Institute of Design in Ulm, Germany. The latter three were all important in spreading the Bauhaus philosophy: Moholy-Nagy and Albers were particularly important in refashioning that philosophy into one suited to the climate of a modern research university in a market-oriented culture; Bill, meanwhile, played a significant role in spreading geometric abstraction throughout the world. Adolf Hitler and Adolf Ziegler visit the Degenerate Art exhibition, 1937. …and they didn’t only go after visual art. Jazz too! De Stijl or Neo Plasticism Theo van Doesburg Arithmetic Composition 1929-30 Theo van Doesburg Key Ideas Like other avant-garde movements of the time, De Stijl, which means simply "the style" in Dutch, emerged largely in response to the horrors of World War I and the wish to remake society in its aftermath. Viewing art as a means of social and spiritual redemption, the members of De Stijl embraced a utopian vision of art and its transformative potential. Among the pioneering exponents of abstract art, De Stijl artists espoused a visual language consisting of precisely rendered geometric forms - usually straight lines, squares, and rectangles--and primary colors. Expressing the artists' search "for the universal, as the individual was losing its significance," this austere language was meant to reveal the laws governing the harmony of the world. Even though De Stijl artists created work embodying the movement's utopian vision, their realization that this vision was unattainable in the real world essentially brought about the group's demise. Ultimately, De Stijl's continuing fame is largely the result of the enduring achievement of its best-known member and true modern master, Piet Mondrian. 1899 Piet Mondrian Alberi, 1908 Piet Mondrian Evening: The Red Tree, 1908-1910 Piet Mondrian The Grey Tree, 1911 Piet Mondrian Neo Plasticism Still Life with Ginger Pot 1, 1911 Piet Mondrian Still Life with Ginger Pot 2, 1912 Piet Mondrian Composition with Oval in Colour Planes II, 1914 Piet Mondrian Composition in Colour A, 1917 Piet Mondrian Composition with Grid IX, 1919 Piet Mondrian Composition with Large Red Plane, Yellow, Black, Gray and Blue, 1921 Piet Mondrian Lozenge Composition with Red, Gray, Blue, Yellow, and Black, 1924 Piet Mondrian Composition with Blue, 1937 Piet Mondrian New York City I, 1942 Piet Mondrian Broadway Boogie Woogie, 1942-43 Piet Mondrian Victoriy Boogie Woogie, 1944 Piet Mondrian