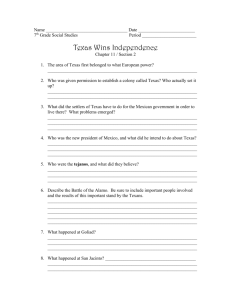

Eyewitness to Texas History – The Runaway Scrape

advertisement

Eyewitness to Texas History – The Runaway Scrape #1 - Muster of the Texan Army and Evacuation of Gonzales, J.H. Kuykendall, March 1836. On the evening of the 13th Mrs. Dickinson and Travis' negro man arrived at Gonzales with the astounding intelligence that the Alamo had been assaulted and taken on the morning of the 6th and all of its defenders slain. Superadded to this news, a rumor became rife that two thousand of the enemy-the advance division of the Mexican army--might be hourly expected at Gonzales. As may reasonably be supposed this news produced intense excitement in our camp. In the little village of Gonzales the distress of the families was extreme. Some of them had lost friends and near and dear relations in the Alamo and now the ruthless foe was at hand, and they unprepared to fly. To facilitate their exit, Gen. Houston caused some of our baggage wagons to be given up to them; but the teams, which were grazing in the prairie, were yet to be found, and night had already set in. In the meantime, orders were issued to the army to prepare as fast as possible to retreat. As most of the companies (all infantry) had been deprived of the means of transportation, all our baggage and provisions, except what we were able to pack ourselves, were thrown into our campfires. Tents, clothing, coffee, meal and bacon were alike consigned to the devouring element. Tall spires of flame shot up in every direction, illuminating prairie and woodland. About ten o'clock one of the captains marched his company to Gen. Houston's tent and said: "General, my company is ready to march" The general, in a voice loud enough to be heard throughout the camp, replied: "In the name of God, sir, don’t be in haste—wait till all are ready and let us retreat in good order." #2 - The Muster and retreat of Houston's army at Gonzales narrated by Creed Taylor, 1900. From the Lavaca, which we crossed a few miles below the present town of Hallettsville, to the Brazos and even beyond, we were not out of sight of refugees. The country east of the Brazos was flat and low and, in many places, owing to the heavy rains, was covered with water, and here the real trouble began. People were trudging along in every kind of conveyance, some on foot carrying heavy packs. I saw every kind of conveyance ever used in that region, except a wheelbarrow, but hand-barrows, sleds, carts, wagons, some drawn by oxen, horses, and burros. Old men, frail women, and little children, all trudging along. And though I have passed through the fields of carnage from Palo Alto to Buena Vista, I have never witnessed such scenes of distress and human suffering. True there was no clash of arms, no slaughter of men and horses, as on the field of battle, but here the suffering was confined to decrepit old men, frail women, and little children. Of course there were hundreds of incidents, tragic and otherwise, occurring in the course of the wild scamper over the almost trackless and rain-soaked prairies, and in crossing swollen streams. Delicate women trudged alongside their pack horses, carts, or sleds, from day to day until their shoes were literally worn out, then continued the journey with bare feet, lacerated and bleeding at almost every step. Their clothes were scant, and with no means of shelter from the frequent drenching rains and bitter winds, they traveled on through the long days in wet and bedraggled apparel, finding even at night little relief from their suffering, since the wet earth and angry sky offered no relief. Despite all this exposure to the elements, not one of our family suffered from sickness. And just here I want to record that more and greater humanity in its most exalted nature was displayed by these unfortunate people, one toward another, than I have ever witnessed. There were no strangers or aliens encountered along this terrible journey. All were friends, comrades and countrymen, with that fellow feeling which endeared a feeling of wondrous kindness one towards another. Fort Worth ISD Social Studies Department 7th Texas History 2015 #3 - The Runaway Scrape by Mrs. Kate Scurry Terrell, 1898. The cry of "Mexicans," though of daily occurrence, always created a panic. Bedding, provisions, any and everything, would be thrown off to lighten the wagons, and the horses whipped into a run. The prairie at times was white with feathers emptied from beds, and the road lined for miles with household goods. Mrs. Anson Jones, wife of the last President of the republic, tells of camps suddenly abandoned, where trunks were left open from a hasty rummage for some needed article, and mirrors were left hanging on the trees. Danger from the disaffected Indians was another source of alarm. A solitary horseman across the prairie would often cause a stampede. Soon hunger and sickness added their gaunt forms to the general distress. Women sank by the roadside from exhaustion, and many little children died. The stronger women became veritable Sisters of Mercy as they went about nursing, encouraging, and comforting the less fortunate. General Rusk pays a glowing tribute to these noble women. He said: "The men of Texas deserved much credit, but more was due the women. Armed men facing a foe could not but be brave; but the women, with their little children around them, without means of defense or power to resist, faced danger and death with unflinching courage." #4 - The Runaway Scrape by Uncle Jeff Parsons, slave of the Sutherland Family, 1850’s. I can't begin to describe the scene on the Sabine. People and things were all mixed, and in confusion. The children were crying, the women praying and the men cursing. I tell you it was a serious time. Before we started on the "runaway" to the Sabine, we buried the wash tubs, pots, kettles, cooking utensils, and old master's secretary, the same one which his grandson George S. Gayle, had in his possession for a number of years. The Mexican army never found them, but they swept the country of poultry, sheep, hogs, and horses. On our return we found nothing but the wild animals on the prairies, and hard times met us at home. We had to live there months on game and without the taste of bread. We built scaffolds for drying the meat. We ate it dried, fried, boiled, broiled, stewed, baked and roasted, but we had to live on it so long we became tired of it, anyway we could cook it. Finally at the end of three months we heard a cannon fire on the bay, and it was a joyful sound. It was the signal telling the people that the vessel had arrived and they could come and get supplies. Old master was not long in getting off. He bought ten barrels of flour, three barrels of pickled pork, one hogshead of rice and sugar and coffee. There was a feast on his place when these supplies came. I know the president never smacked his lips with more relish over a Thanksgiving dinner than we did over the first meal we ate after the groceries came. #5 - The Runaway Scrape and Return by Andrew Jackson Sowell, 1884 Several families remained here at Columbia for some time, until the times became more settled. Finally they commenced moving back to their old homes on the Guadalupe and elsewhere, and, in 1838-39, a great many had returned and again settled at Gonzales. I heard of one incident connected with the sudden flight of the settlers on the approach of the Mexicans, which I will here relate. A family who were living some distance from Gonzales, were just sitting down to breakfast when one of the messengers which Houston had sent out arrived and told them of the fall of the Alamo, and the advance of Santa Anna. Without stopping to finish breakfast they hastily collected a few things and fled, and on their return more than a year afterwards, found everything as they had left it. The table was still set, and chairs around it, and moldy bread and meat in the dishes, nothing having molested a thing. Fort Worth ISD Social Studies Department 7th Texas History 2015 #6 - The Runaway Scrape narrated by Creed Taylor, 1900. The Mexicans had been whipped and we had nothing to fear at their bands anymore. As we pushed forward the days seemed shorter and the distance ahead seemed greater than ever before. We had only a small stock of provisions--jerked beef, parched corn--but we didn't feel the pangs of hunger. The night after we crossed the Colorado floods of rain fell and we became thoroughly soaked, but we didn't mind the rain-we were going home. We overtook many other refugees who were returning home and they too, without exception were in high spirits. We expected to find nothing but ashes and a heap of ruins where we had left our homes and shelter, but now this could be borne with resignation since Texas was free and the Mexican power was forever broken. Under the protection of our own rule and with the land at peace, we could soon rebuild our homes, replenish our herds, and as for the Indians we could cope with them. I think it was on the tenth or twelfth of May that we reached home, late in the evening, and we found the house and the outbuildings intact, but the vandals had been there and little of value remained. Fires had been made in the yard, feathers were scattered about the premises and the bones of fowls scattered round told too plainly where mother's chickens had gone. Our rude furniture was broken and the few books she had left on the side-shelf were gone. The crib and the smokehouse were empty. The doors were broken from their wooden hinges. #7 - GONZALES IN 1838 AND 1839. EDITOR GONZALES INQUIRER, 1882 The spring of 1838, witnessed the return to Gonzales of some of the families who had built homes here in the first settling of this country, but who, with others of the colonists on the Guadalupe river, had been constrained to a hasty flight in the memorable running scrape of 1836. The Alamo had been garrisoned principally by men and boys from this vicinity, and when they were butchered, their families were left smitten and almost helpless. The enemy advancing rapidly upon them, their homes were left to the flames while they escaped as best they could. The defeat of the Mexicans at San Jacinto did not secure peace to the western settlements; on the contrary, rumors of intended invasions were rife every spring, and Indian depredations were common. Thus the prospect of good times was remote to the surviving families who had buffeted about until they had mostly used up their personal property, but yet owning excellent lands in this region, they resolved to return, re-establish and rebuild their former homes. This spirit and indomitable energy of these people, was worthy of note, and was exemplified while they were moving from place to place, anxiously waiting for some protection and security to be offered their frontier. #8 - The Runaway Scrape and Return by Mary Cleveland Rusk, wife of Texas Sec. of War Thomas J. Rusk, April 1836."God of battles, remember the helpless! Let thy strength be with us this day!" Towards sunset, a woman on the outskirts of the camp began to clap her hands and shout "Hallelujah! Hallelujah!" Those about her thought her mad, but, following her wild gestures, they saw one of the Hardins, of Liberty, riding for life towards the camp, his horse covered with foam, and he was waving his hat and shouting "San Jacinto! San Jacinto! The Mexicans are whipped and Santa Anna a prisoner." The scene that followed beggars description. People embraced, laughed and wept and prayed, all in one breath. As the moon rose over the vast flower-decked prairie, the soft southern wind carried peace to tired hearts and grateful slumber. As battles go, San Jacinto was but a skirmish; but with what mighty consequences! The lives and the liberty of a few hundred pioneers at stake and an empire won! Look to it, you Texans of today, with happy homes, mid fields of smiling plenty, that the blood of the Alamo, Goliad, and San Jacinto sealed forever "Texas, one and indivisible!" Fort Worth ISD Social Studies Department 7th Texas History 2015