II Identifying Public Access and Success Programs

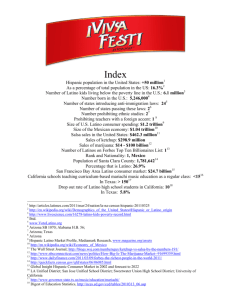

advertisement