Eugenie A. Samier (The British University in Dubai

advertisement

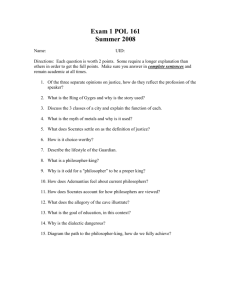

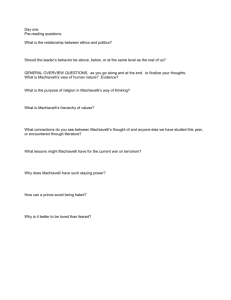

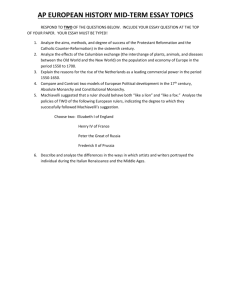

Abstract for CASEA/CCEAM, Fredericton June 6-10, 2014 Due date, October 1, 2013 Theme of Conference “(Re) Situating Commonwealth: Educational Leadership at a Time of Demographic Change” Eugenie A. Samier Associate Professor The British University in Dubai Dubai International Academic City Block 11, Floor 1 PO Box 345015 Dubai, United Arab Emirates Eugenie.samier@gmail.com Peter Milley, PhD Professeure Adjoint / Assistant Professor Faculté d'éducation / Faculty of Education Université d’Ottawa | University of Ottawa pmilley@uottawa.ca Tél. | Tel.: 613-562-5800 (1458) Téléc | Fax: 613-562-5146 145 Jean-Jacques-Lussier (487) Ottawa ON Canada K1N 6N5 www.uOttawa.ca Dr. Carol Harris Professor Emeritus, University of Victoria Adjunct Professor, Acadia University 3 Prince Street Wolfville, B4P 1P7 harrisce@uvic.ca Abeer Al Rasbi EdD Student The British University in Dubai Dubai International Academic City Block 11, Floor 1 PO Box 345015 Dubai, United Arab Emirates abeer.alrasbi@gmail.com Title of Symposium (E. A. Samier, P. Milley & C. Harris): Educational Leadership and the Securitization of Education: The Challenges of Individual, Organizational and System Threats to Security Eugenie A. Samier (The British University in Dubai, UAE) Introduction: Towards a Taxonomy of Securitized Education for Educational Leadership This symposium of papers explores various dimensions and levels of security issues in contemporary and globalized education, ranging from individual and group security on an organizational level in the first two papers, to internationalised education through globalisation as a cultural security threat in the context of developing countries in the third. Each of the papers draws on critical perspectives in constructing an examination of securitisation of education. Peter Milley uses Habermasean communicative and strategic analysis to investigate the abuse of power and emotional manipulation in organizational action as it affects individuals. Carol Harris uses a Machiavellian analysis through the lens of Bobbitt’s perspective on Machiavelli as an ‘intense moralist’, combined with Collingwood’s historicist principles, to explore the security of educational organizations under neoliberalism. The final paper by Eugenie Samier examines the cultural security threat of exported neoliberal education through globalisation through the critique of the Copenhagen School of Cultural Security. Collectively, these papers present a theoretical and conceptual scaffolding upon which to build a theory of educational security as both a critique and an aim, in the spirit of critical theory. Peter Milley (University of Ottawa) Overt and Covert Strategic Maladministration, Insecurity, and the Problem of Passive Evil in Educational Organizations In 2008, Eugenie Samier broke new ground in the study of administrative ethics in education with her article “The Problem of Passive Evil in Educational Administration: Moral Implications of Doing Nothing.” She cast light on the issue of moral passivity among those who witness unethical administrative behaviours but fail to respond, and described how this behaviour is conditioned by, and complicit in, “the everyday cruelties and moral lapses taking place within the ranks of [educational] administrators” (p. 2). Samier brought to the fore the negative effects of this “moral muteness” on the psychological, emotional and economic security of organizational members. Following Adams and Balfour (1990), she called for conceptual frameworks that could elucidate the problem of passive evil and support the reclamation moral agency in educational organizations. My paper responds to this call. In it, I draw on Habermas’ (1984; 1989) model of social action to extend Samier’s (2008) analysis. Having previously adapted Habermas’ model to investigate moral, political and emotional dimensions of educational administration (Milley, 2001; 2008; 2009), I argue that it is suitable for examining the moral failings, abuse of power and emotional manipulation that are at the heart of the problem of passive evil. Following Habermas (1984; 1989), it is possible to distinguish two fundamental types of organizational action: Communicative and strategic. Communicative action exists when organizational members interact on a consensual basis to set goals and coordinate their activities. It takes place through inclusive conversation, trustworthy communication, and genuine reciprocity. Strategic action is when members interact with the main purpose of achieving individual or organisational goals. Both forms of action are legitimate and necessary, though strategic actions, such as the overuse of role authority to get results, often reach inappropriate levels in organizations and lead to significant conflicts. However, situations can become particularly dysfunctional and morally disturbing when someone consciously sets out with malicious or immoral strategic intent to overtly or covertly manipulate others (e.g., intimidation, lying, distorting communication). Things can be even more problematic when someone is self-deceived in their intent. In such cases, she or he may act in ways that are immoral while construing her or his actions to be legitimate and in the best interests of the affected parties (e.g., serial abusers). Habermas (1970; 1984; 1989) observes that this self-deception stems from systematic distortions in inter- and intrasubjective understandings and is often attended by pathologies. Drawing on these concepts, I frame passive evil in educational organizations as a dysfunctional and pathological phenomena stemming from overt, concealed and unconscious forms of strategic action that are grounded in malicious or immoral intent. I offer an account of how moral passivity settles in for organizational members at conscious and subconscious levels, conditioned in part by defensive routines and self-deceptive rationalizations. I also provide an inventory of the overt and covert tactics used by those with bad intent to foster moral passivity. I offer insights about how moral agency might be reclaimed in educational organizations through the recuperation of communicative practices that make the organization safer and more secure for its members. [words: 499] References Adams, G. and Balfour, D. (1998) Unmasking administrative evil. Thousand Oaks: Sage. Habermas, J. (1970). On systematically distorted communication. Inquiry: an interdisciplinary journal of philosophy, 13(1-4): 205-218. Habermas, J. (1984). The theory of communicative action: Reason and the rationalization of society. T. McCarthy (Trans.). Boston: Beacon Press. Habermas, J. (1989). The theory of communicative action: the lifeworld and the system. T. McCarthy (Trans.). Boston: Beacon Press. Milley, P. (2002). Imagining good organizations: Moral orders or moral communities? Educational management administration and leadership, 30(1): 47-64. Milley, P. (2008). On Jürgen Habermas’ Critical Theory and the Political Dimensions of Educational Administration. In E. Samier & A. Stanley (Eds.), Political approaches to educational administration and leadership (pp. 54-72). New York: Routledge. Milley, P. (2009). Towards a Critical Theory of Emotions in Educational Leadership and Administration: Building on Concepts from Jürgen Habermas. In E. Samier & M. Schmidt (Eds.), Emotional dimensions of educational administration and leadership (pp. 65-82). New York: Routledge. Samier, E. (2008). The problem of passive evil in educational administration: Moral implications of doing nothing. International Studies in Educational Administration, 36(1), 2-21. Carol E. Harris Reading Machiavelli in Preparation for Educational Leadership: Reclaiming a Secure and Realistic Perspective on Organizational Politics Possibly no historical figure has provoked a stronger emotional response from organizational leaders than Nicolo Machiavelli, seen variously as the epitome of evil or as a sensible realist dispensing wise words of advice. Although he addressed his advice on leadership to a Medici prince in the context of 16th century Italy, Machiavelli is read carefully today by certain scholars of leadership and organizational theory (e.g., Migone, 2008; Hodgkinson, 1991), and avoided assiduously by others in these fields. In this paper, I argue that educational leadership programmes would (and occasionally do) benefit immensely from a close examination of Machiavelli’s work. My perspective joins a growing body of administrative theory which includes realistic portrayals of both ethical action within institutions and ‘organizational evil,” be the latter either passive (Samier, 2008) or intentional (O’Day, 1974). This critical view, I argue, provides useful guidelines for action in the field, and restores much needed credibility to university preparation programmes dominated by market imperatives. Recently, American author, academic and military/policy strategist Philip Bobbitt has reignited the controversy around Machiavelli, portraying him as an ‘intense moralist’ who faced difficult but unavoidable decisions not unlike those met today by world leaders. It is difficult to read Bobbitt without drawing a parallel between decisions promoted by Machiavelli and political moves made by today’s politicians, most notably Obama in the American context. Colin Burrow (2013) joins other reviewers of Bobbitt’s interpretation, warning that Machiavelli’s major message is that the state must be saved at any cost. This message may well be applied ruthlessly by contemporary leaders. In this paper, following philosopher and historian R.G. Collingwood, I argue that both interpretations miss the appropriate application of Machiavelli for today. First, past events should be read historically by placing oneself in the described time, place and political situation. Second, events must be read critically, interpretively, and imaginatively in an attempt to uncover one’s own presuppositions as well as those of historical actors. From Collingwood’s (1936;1965) work on historical understanding, I extract the theme of imaginative and critical reconstruction and from his political writings, I examine the concept of underlying beliefs, meanings and values (presuppositions) that can be illuminated most effectively through artistic and linguistic expression. Lessons, drawn from The Prince and based on my own teaching experience at a Canadian university, explore Collingwood’s historicity under three topics: the human condition; the establishment of new organizations; and politics and morality. From the messages of Machiavelli, I consider four benefits to organizational leaders and other members of the organization as they: 1. Recognize power grabs in their pure, raw form; 2. Combat moves that are counter-productive to personal and collective well-being; 3. Apply common sense approaches to building organizations and maintaining their strength; and 4. Explore an approach to history that calls for context (social, political and economic) and interpretation, as well as informed imagination. Together, these benefits augment educational security insofar as they further, in potential leaders, an enhanced understanding of intellectually honesty, imagination, and authentic social relationships. [Words: 495] References Burrow, C. (2013). Modern model of an intense moralist. The Guardian Weekly, 189, 8, 3639. Bobbitt, P. (2013). The garments of court and palace: Machiavelli and world that he made. Grove Press. Collingwood, R.G. (1965). Essays in the philosophy of history. Austin: University of Texas Press. Collingwood, R.G. (1936). Human nature and human interest. Paper of the Royal Academy, May 20. Hodgkinson, C. (1991). Educational leadership: The moral art. New York: SUNY Press/ Migone, A. (2008). Beyond foxes and lions: Machiavelli’s discourse on power and leadership. In E.A. Samier & A.G. Stanley (Eds.), Political approaches to educational administration and leadership (pp.23-36). London: Routledge. O’Day, R. (1974) ‘Intimidation Rituals’, Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 10, 3: 37386. Samier, E. (2008). The problem of passive evil in educational administration, International Studies in Educational Administration, 36 (1), 2-21. Eugenie A. Samier (The British University in Dubai, UAE) and Abeer Al Rasbi (The British University in Dubai, UAE) Globalized Western Education as a Cultural Security Threat: Undermining the ‘Common Weal’ of Developing Countries in the Arabian Gulf through Intellectual Recolonisation? The main thesis of this paper is to advance a new approach to the critique of globalised education: as a cultural security issue. While globalisation as a neoliberal transnational economic movement has been criticised for commercialising education, altering the nature of knowledge, the role of students and faculty, and the nature of curriculum and pedagogy, little attention has been paid to the role of the university in particular through its globalisation activities in the non-‘Western’ or developing world as a cultural security threat carried out by non-state actors (e.g., Kirchner & Sperling, 2010), in this case foreign universities and teaching faculty. Drawing on the recent expansion of security studies beyond the military and traditional security sector, into human (e.g., Tadjbakhsh & Chenoy, 2007; Tehranian, 1999), societal (e.g., Buzan, 1983) and cultural security (e.g., Friedman & Randeria, 2004) through the work primarily of the Copenhagen School of Cultural Security (e.g., Buzan, Wæver & de Wilde, 1989) this paper regards society and culture as referent objects of security in their own right, and their ability to maintain ethno-national identities (Roe, 2010). This paper examines culture, religion and identity from a security perspective that regards the nature of globalised university in both tangible (objective) and intangible (subjective) security threat to the integrity of indigenous culture and religion. The UAE, one can argue, in the cultural sphere is subject to threats under the new imperialism of globalised education and related intellectual ‘products’ through imported consulting, and management and leadership programmes that collectively have a potential eroding effect on cultural traditions, traditional political institutions, an Islamicised worldview, and national identity: 1. Imported curriculum and teaching that privileges a secularised worldview and values; 2. Western cultural precepts in administration and leadership that reflect their jurisdictional characteristics and transmit foreign models of authority, leadership, and political legitimacy; 3. Cultural practices of foreign staff (in the UAE higher than 80% of total population), many of whom work in sensitive policy and management levels and in higher education; 4. Potential higher education impact on other societal sectors such as the economy, politics, the family, culture and religion (e.g., Katzenstein, 1996); and 5. The neglect and exclusion of a vast, rich, and varied Islamic and Arab scholarship. Part of this study illustrates these issues as they relate to Emirati women rising into higher education leadership positions in the context of a university case study. The thesis presented here also draws on the issues discussed by Williams (2007) in the symbolic forms of power that shape the cultural security problem, by drawing on Bourdieu’s concepts of the interplay between culture and strategy in his critique of Western domination, and as it complements a critical theory and post-colonial critique of industrialised Western hegemony in economic, political, and cultural spheres of the developing world as it is created and carried in higher education as it applies to the Arabian Gulf with a focus on the United Arab Emirates. References: Buzan, B. (2007) People, States and Fear: The National Security Problem in International Relations, 2nd edn. Wivenhoe Park, UK: ECPR Press. Buzan, B., Wæver, O. and de Wilde, J. (1998) Security: A New Framework for Analysis. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner. Roe, P. (2010) ‘Societal security’, in A. Collins (ed.) Contemporary Security Studies (202217). 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Friedman, J. and Randeria, S. (eds) (2004) Worlds on the Move: Globalization, Migration and Cultural Security. London: I. B. Tauris. Katzenstein, P. (ed.) (1996) The Culture of National Security: Norms and Identity in World Politics. New York: Columbia University Press. Kirchner, E. and Sperling, J. (eds) (2010) National Security Cultures: Patterns of Global Governance. Abingdon: Routledge. Tadjbakhsh, S. and Chenoy, A. (2007) Human Security: Concepts and Implications. London: Routledge. Tehranian, M. (ed.) (1999) Worlds Apart: Human Security and Global Governance. London: I. B. Tauris. Williams, M. (2007) Symbolic Power and the Politics of International Security. Abingdon: Routledge.