HIS 18 – Part 2

advertisement

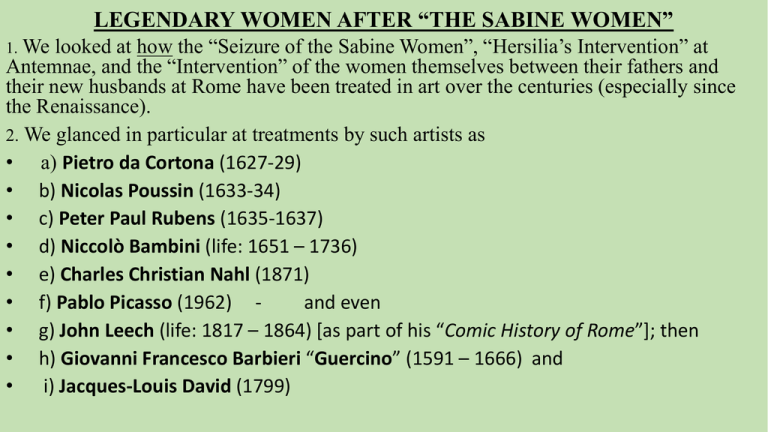

LEGENDARY WOMEN AFTER “THE SABINE WOMEN” looked at how the “Seizure of the Sabine Women”, “Hersilia’s Intervention” at Antemnae, and the “Intervention” of the women themselves between their fathers and their new husbands at Rome have been treated in art over the centuries (especially since the Renaissance). 2. We glanced in particular at treatments by such artists as • a) Pietro da Cortona (1627-29) • b) Nicolas Poussin (1633-34) • c) Peter Paul Rubens (1635-1637) • d) Niccolò Bambini (life: 1651 – 1736) • e) Charles Christian Nahl (1871) • f) Pablo Picasso (1962) and even • g) John Leech (life: 1817 – 1864) [as part of his “Comic History of Rome”]; then • h) Giovanni Francesco Barbieri “Guercino” (1591 – 1666) and • i) Jacques-Louis David (1799) 1. We 3. And we saw how no known depictions of this legendary event survive from the Roman period until 89 BC when the seizure (“rape”) of the women is a theme on some of the coin issues of the moneyer Lucius Titurius Sabinus. TARPEIA 1. In the midst of the events surrounding the seizure of the Sabine women and the return of their parents seeking restitution, another woman, TARPEIA, played a treacherous role – at least according to some historians of the Roman period, including Livy. 2. In Livy’s account [Book 1. 11] • The fathers of the Sabine women had planned their assault on Rome well and it was backed by treachery. • The commander of the Roman citadel, Spurius Tarpeius had a daughter, TARPEIA, a young girl, who had gone outside the walls to fetch water. • She was bribed by the Sabine king, Titus Tatius, to admit a party of Sabine soldiers into the citadel. • Once inside, the soldiers crushed her under their shields to make it look as if they had taken the place by storm or to show that there must be no trust of a traitor. • There was also a story, Livy continues, that she had demanded as her price what was on the soldiers’ shield-arms, by which she meant the heavy gold bracelets and fine jewelled rings the Sabines wore, but they rewarded her with the shields they were carrying. 2. Juxtaposing the two accounts Livy emphasizes the female ideal and its antithesis: a) the Sabine women, though foreigners who have become Romans by force, show loyalty both to their parents and to their husbands, reconciling the two, whereas b) Tarpeia, though Roman by birth, shows a greed which fails her father, her country, and her gods. 3. But Livy’s is not the only version. • The contemporary of Livy, the Augustan poet PROPERTIUS, does not see TARPEIA so much as a traitor but as a woman torn between her love for the Sabine king and her duty to country. • She realizes the implications of her love but sees how, by marrying Titus Tatius, she will, like the Sabine women, combine marriage and peace-making. • Her hope is that the two communities, Roman and Sabine, will come together – just as marriage brings two families together and strengthens society. • Tarpeia’s story has also been a theme for sketches and some paintings over the centuries too (including a painting by a follower of Giulio Mazzoni): TARPEIA MAKES A DEAL TARPEIA ADMITS SABINE TROOPS INTO THE ROMAN CITADEL FANCIFUL DEPICTIONS OF TARPEIA’S FATE “THE PUNISHMENT OF TARPEIA” - AFTER THE SCHOOL OF GIULIO MAZZONI (1525 – 1618) Tarpeia does not appear in any known pictorial presentation during the Roman period until 89 BC when, again, the moneyer Lucius Titurius Sabinus made her death a theme for some of his coin issues: LUCIUS TITURIUS SABINUS, MONEYER IN 89 BC. HE STILL REFERS TO THE SABINE KING TITUS TATIUS BUT ON THESE COINS RECORDS THE FATE OF TARPEIA. But then she appears again on the state’s coinage some seven decades later under the first Princeps, Augustus (27 BC – AD 14) when the moneyer Publius Petronius Turpilianus (active from 19 to 4 BC) again made her story a theme. THE HEAD OF AUGUSTUS AND TARPEIA OVERWHELMED BY THE SHIELDS OF THE SABINE TROOPS PUBLIUS PETRONIUS TURPILIANUS CHOSE (FOR NO CLEAR REASON) TO RECORD TARPEIA’S FATE Tarpeia’s fate is also depicted on a relief on part of the Basilica Aemilia (originally erected in 179 BC) in the Roman Forum, the relief itself seemingly belonging to the first century AD rather than earlier. A FRIEZE IN THE BASILICA AEMILIA IN THE FORUM ROMANUM (usually dated to the first century AD) Tarpeia’s greatest claim to fame in antiquity was, perhaps, her lending her name to the infamous ROCK in Rome (“the Tarpeian Rock”) from which the convicted, especially traitors, were very occasionally thrown. But whether the rock was named after her or her story was ‘invented’ to explain the name of the rock isn’t clear. ARTIST’S IMPRESSION OF THE TARPEIAN ROCK FROM WHICH TRAITORS WERE VERY OCCASIONALLY CAST Continuing with “the period of the kings”, we should not omit the role of TANAQUIL, the foreign wife (who became Roman) of King Tarquin I – although later artists do not appear to have been eager to represent her pictorially. TANAQUIL Livy [1.33] tells how …… • in the Etruscan state of Tarquinii an aristocratic young woman named TANAQUIL married Lucumo, the son of a Greek refugee. • Her husband seemed unlikely to advance in his career there since he was not of pure Etruscan descent. • Determined to see Lucumo enjoy the respect he deserved, TANAQUIL “smothered all feelings of natural affection for her native town and determined to abandon it for ever.” • The couple moved to Rome as emigrés and bought a house, Lucumo changing his name to ‘Lucius Tarquinius Priscus’. • Establishing his reputation, Tanaquil’s husband became well known to King Ancus Marcius [traditional dates 642-617 BC] and was eventually chosen as his successor (no doubt encouraged by his wife). • When Tarquinius, after a 37-year reign, was fatally attacked by the sons of his predecessor, TANAQUIL, hiding his death, urged her young protégé, Servius Tullius, to prepare himself to take over the throne. • TANAQUIL then hurried to an upper window in the palace and began to address the gathering crowds. • “She declared that the king had been stunned by a blow, had suffered only a superficial wound and was already recovering”. • She begged them, in the meantime, to give their support to Servius Tullius who would see the attackers of the king brought to justice and who would deputize for the king. And so TANAQUIL played a role both by urging her husband on and by manipulating the situation after his death and was successful in putting two of Rome’s kings on the throne. Furthermore, she was the ‘mother’ or ‘grandmother’ (Livy was unsure which) of the final king, Tarquinius Superbus [Tarquin II] who ruled tyrannically and was expelled from the state with the whole Tarquin clan, bringing the monarchy to an end. To Romans of the historical period it is likely to have been a matter of concern that a woman (a foreign woman at that) had such influence in the political affairs of the state. LUCRETIA 1. a) The “tyrannical” rule of the second Tarquin (Tarquinius Superbus) brought the Tarquins into disrepute. b) But it was the behaviour of a particular member of the family, Sextus Tarquinius, in forcing himself on the noblewoman LUCRETIA which, more than anything, led to the expulsion of the whole clan (gens) and the overthrow of ‘kings’ for ever. 2. a) Sextus, developing a passion for Lucretia, raped her and rode away. b) She wrote to her father and her husband begging them to come to her. 3. When asked whether she was well, she replied: “No. What can be well with a woman who has lost her honour? …. My body only has been violated. My heart is innocent, and death will be my witness.” This Livy’s account. 4. Livy then relates how she made both her father and her husband promise to avenge her. 5. He continues: a) “The promise was given. One after another they tried to comfort her. They told her that she had been helpless and, therefore, innocent; that Sextus alone was guilty. b) It was the mind, they said, that sinned, not the body: without intention there could not be guilt. ‘What is due to him,” Lucretia said, “is for you to decide. As for me, I am innocent of fault, but I will take my punishment. Never shall Lucretia provide a precedent for unchaste women to escape what they deserve.’ 6. With these words she drew a knife from under her robe, drove it into her heart, and fell forward, dead.” Lucretia’s story has been almost endlessly depicted by artists: Tiziano Vecelli (TITIAN) (ca 1488/90 – 1576) [In the Fitzwilliam Museum] Hans von Aachen (1552 – 1615) Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) Artemisia Gentileschi (1593 - ca 1656) [The Earliest Female Artist to depict the Theme] Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606-1669) Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) Felice Ficherelli (1605-1660) (late 1630s) Giuseppe Maria Crespi (1665-1747) Lucas Cranach the Elder (ca 1472 – 1553) Jacopino del Conte (1510 – 1598) [1532] Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606-1669)