Congo DEMO PAPER #1

advertisement

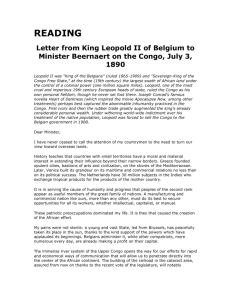

Smith 1 Kendall Smith Senior Demonstration Plaehn April 5, 2012 “Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely” –Lord Acton The Congo Crisis An old Congolese saying goes, “Death does not sound a trumpet.” In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where about 1,200 people die a day, all one can hear is silence. Silence in the newspapers, silence in the radios, and silence from international powers. Three works written to rupture the silence are King Leopold’s Ghost by Adam Hochschild; Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad; and Blood River by Tim Butcher. Hochschild’s historical account takes on the silence of the Belgian men and women working under the reign of King Leopold II, who personally owned the Congo Free State from 1885-1908. Conrad offers a personal perspective on the atrocities of Leopold’s Congo in his fictional account based on the experiences he encountered during his time working in the Congo Free State. In 2004, Butcher physically followed the trail of Henry Morton Stanley up the Congo River, and meets a world of corruption and death on the way. These three narratives come from three very different perspectives; one of a journalist, one of a historian, and one of an explorer, yet they all connect through their astounding theme: absolute power. Each storyline contains a main character with absolute power, who then uses that power to take complete advantage of the Congolese and their country. The case of imperialism in the Congo attracts attention because many countries have dealt with “a colonial rule that was cruel and racist,” but those countries have recovered, the Congo has not. Take Malaysia for example: they received “independence at roughly the same time as the Smith 2 Congo…but somehow Malaysia got through it and the Congo didn’t” (Butcher 310). Absolute power played a huge role in destroying the Congo if it was not “cruelty” or “racism.” The Congo remains impoverished and helpless not primarily due to a lack of money, or even European racism, but because each successive ruler has been corrupted by absolute power—because no one knew just how right Lord Acton could be. The concept of absolute power in the Congo began with the infamous King Leopold II, who single-handedly ruled the Congo Free State for twenty-three years, yet never set foot on Congo soil. This means that of the 10 million men and women who died in the Congo as a direct result of his actions, not one ever looked the King in the eyes (Hochschild 3-4). Leopold easily covered up the deaths in the Congo; he took charge of all the newspaper articles and letters published about the situation in the Congo Free State. He did not care about the death toll; the only piece of the Congo puzzle that mattered to Leopold was money. Hochschild writes, “what mattered was the size of the profit…a desire not only for money, but for power” (39). Leopold searched for power so intensely in Africa because he could not attain any power in Europe due to the small size of Belgium. His superiority complex, which remained present throughout his life, even drove his closest family members away from him (40). But Leopold did not need family as long as he had his huge African empire, which he attained by charming political leaders and Christian humanitarians into thinking he only wanted the Congo for philanthropic reasons. A French diplomat, who fell under Leopold’s charm, once stated Leopold’s plans would become “‘the greatest humanitarian work of this time”’ (Hochschild 46). Leopold’s natural ability to manipulate became central to obtaining power. He even managed to get the Congo Free State all to himself without letting the Belgian government have a slice of the “‘magnificent African cake”’ (58). The more power hungry he got, the more determined he became to acquire power. Smith 3 He achieved this by creating several fake philanthropic organizations including the “International Association of the Congo” and the “International African Association” (65). No differences between the two organizations ever came to life, but that did not matter because the European powers recognized the associations and started giving money to them. Leopold knew that in Africa, more money always equaled more power. Leopold knew their was enough money hidden in the resources of Africa to make him the absolute ruler, so his only real distress came from getting money to fund his projects in the Congo. He knew the Congo would eventually return the money borrowed through profits, but he needed money to start with. At first, he could not ask the Belgian government for the money because he promised the Parliament that the Congo Free State “would never be a financial drain on Belgium” (91). He slowly received money from investors looking to get rich off the ivory and humanitarians hoping to stop the slave trade in Africa. He eventually even convinced the Belgian Parliament that if they funded his projects in the Congo, he would leave the Congo to Belgium in his will (94). With the money he received from donors and Parliament, Leopold sent steamships with young, hopeful European men to collect ivory and bring it back to Europe. Some of these men went along with the atrocities they saw daily during their trips. But others, like Joseph Conrad and George Washington Williams, hurried back to Europe to get word out about the mayhem. Conrad later wrote, “‘The word ‘ivory’ rang in the air, was whispered, was sighed. You would think they were praying to it’” (Conrad 23). The profit made from ivory, and later rubber, consumed Leopold; the more money he made on ivory, the more power he gained in Europe and Africa. The more money he had, the more he could expand. The Congo was just the beginning of Leopold’s plans; Hochschild explains, “the Congo alone was never enough to satisfy him. Fantasizing an empire that would encompass the two legendary rivers of Africa, the Congo and Smith 4 the Nile” (167). Fortunately, Leopold’s dreams never came true and his absolute power was limited to the Congo. Even though Leopold attained the money to send to the Congo Free State, he knew absolute power required more than just money; rulers in power needed followers. The next piece of the puzzle for Leopold was figuring out how to make both the white and black men in the Congo obey him, a strategy Mobutu would later use as well. To this day, people remain fascinated by how Leopold managed to manipulate so many groups entirely on his own. He started by handpicking a small group of “high and middle level administrators, and a mini cabinet of three or four Belgians at the top [who] reported to Leopold directly” (116). This may have been Leopold’s smartest move because he created a process where everything relied on him. He engraved in the minds of these men that every decision had to go through him and that no one else had a say in the Congo. No one could have more power than he did. This strategy proved to be incredibly successful as no one dared to challenge Leopold’s power during his first few years of reign in Africa. As Hochschild says, “in the Congo there was no stooping; Leopold’s power was absolute” (116). This quote proves that Leopold’s power was simply “absolute.” However, while Leopold used his power to exploit the Congolese and their resources, he did not see his precious rule as one of violence: The Congo in Leopold’s mind was not the one of starving porters, raped hostages, emancipated rubber slaves, and severed hands. It was the empire of his dreams, with gigantic trees, exotic animals, and inhabitants grateful for his wise rule. (Hochschild 175) This quotation displays how conceited and blind Leopold was. Since he never actually ventured to the Congo, he never saw his orders come to life in the forms of “severed hands” and “raped hostages.” He saw the Congo as he pleased. The scariest type of power comes when the one with Smith 5 the power does not even want to see what he or she has done. When even the ruler realizes that he has become so far entrenched in evil that he cannot turn back. No better example of this comes to mind than Leopold’s Congo. Leopold’s absolute power in the Congo inspired Joseph Conrad to create a fictional character with immense power in his own narrative. While Hochschild’s book gives the reader a historical account of Leopold’s atrocities in the Congo Free State, Joseph Conrad presents a fictionalized eyewitness account. Hochschild describes Conrad as an “open-eyed observer who caught the spirit of a time and place with piercing accuracy” (149). Hochschild recognizes that the reign Mr. Kurtz’s deploys over the native people in Heart of Darkness is a reflection of Leopold’s rule over the Congolese. Heart of Darkness presents itself as a work of fiction with made up characters, but the book is based on Conrad’s personal experiences in the Congo and the people he met there. The most widely talked about character, Mr. Kurtz, is not a figment of Conrad’s imagination, but rather a combination of the most grotesque men working in the Congo at the time of Conrad’s journey. One of these men, who placed severed heads as “decoration round a flower bed in front of his house” (Hochschild 145) just like Mr. Kurtz, was Léon Rom. He rose as a Force Publique officer, the group Leopold created to inflict punishment on the local Congolese when they did not follow orders, and soon became one of the most monstrous Captains in the Congo (Hochschild 137). He fell into the Congo allure like many other young men, for the Congo brought one aspect of life these men did not have in Europe: absolute freedom. Freedom leaves room for corruption, and these men became incredibly corrupted. One officer wrote back home “‘We have liberty, independence, and life with wide horizons. Here you are free and not a mere slave of society…Here one is everything! Warrior, diplomat, trader!! Why not!’” (137). This type of freedom made the rise to power very easy in the Congo, even if it Smith 6 was not much power in reality, to these men it seemed as if they ran the world. They believed they had absolute power. These men with complete freedom and power lost their sense of morals very quickly in the Congo. Conrad’s character Kurtz represents one of the men who left their “bourgeois morality back in Europe” (Hochschild 138). Kurtz’s infamous quote “‘Exterminate all the brutes!”’ shows the reader just how detached these young men were from European morals and values (50). In the Congo, they could connect with their innate barbaric thoughts. Kurtz’s reference to the native Congolese as “brutes” is filled with irony because in reality the young European men inhabited “brutish” personalities. Marlowe even says, “‘You can’t judge Mr. Kurtz as you would an ordinary man’” (56). Conrad writes this in his book to demonstrate how the mentality of men in the Congo really did change. These men could exploit and kill whomever they pleased; the men received more power than they could handle. Kurtz symbolizes the epitome of a man who lost his morals when given absolute power. Marlowe attributes this as, “‘All of Europe contributed to the making of Mr. Kurtz”’ (49). Conrad explains to the reader that all of the men and women back in Europe who supported the ivory market and the actions of Leopold were the ones who kept men like Mr. Kurtz exploiting the Congo. Even the people who only sent money to the Congo and did not partake in any violent acts against the Congolese deserve the same amount of guilt. They just paid other people to do it for them. The same is true today of the millions of people who support companies such as Apple, Panasonic, Dell, and Nintendo. The products made by these companies need a resource called coltan (Butcher 24). Millions of Congolese children mine coltan everyday in dangerous working conditions. This means that supporters of Apple are unknowingly funding the deaths of millions of Congolese Smith 7 children. Leopold’s manipulation from absolute power set in place a system of perilous financial support that still remains in place today. The worst part of absolute power is how it constricts the beholder so tightly that the beholder cannot escape it. Kurtz ‘“hated [the Congo] and somehow he couldn’t get away’” (56). He could not escape because he got so attached to the power. Once one receives that kind of power over people, he or she cannot just go back to having to little or no power without serious psychological effects. Kurtz knows that if he returns to Europe, he will have nothing. Not because he could not obtain a job in Europe, but rather because nothing will ever be as good as absolute power. Even the natives fell under Kurtz’s spell, as they would literally “crawl” on their hands and knees to him (58). The people, whose lives he destroyed, worshiped him. This also explains why he stays worried that other men are hunting for his job throughout the book. He cannot let go of his power; absolute power had completely constricted him. Conrad presents Kurtz’s physical sickness in the book as a metaphor for the mental sickness of men like Léon Rom whose “‘appetite for ivory had got the better of—what shall I say—less moral aspirations’” (57). The addition of absolute power forced Kurtz to lose sight of who he was before he reached the Congo, a transformation that consumed many men working under King Leopold II. As these men became more powerful, their craving for money grew and their racist behaviors worsened. Absolute power stemmed from racism and the desire for money, but was not limited to King Leopold II’s reign over the Congo Free State. More recently, Joseph Désiré Mobutu took the title of most corrupt ruler. Mobutu’s first step as dictator brought the country back 100 years by renaming everyone and every place to a tribal name. This included the country itself, which returned to the name Zaire. Over the next thirty years, “his personal wealth at its peak was estimated at 4 billion [dollars]” (Hochschild 304). Where did all this money come from? Zaire’s Smith 8 very own rubber market; the exact same place Leopold gained his wealth from in 1894. His dictatorship stood “as a perfect example of a kleptocracy, a state where rampant greed and corruption erode normal economic activity” (Butcher 238). He stole straight from his own country, and no one dared to stop him. He did not even have to earn this kind of power: it was given to him straight from Western powers who feared the Congo would fall to Soviet influence during the Cold War. Hochschild portrays the relationship as: The Western powers had spotted Mobutu as someone who would look out for their interests. He had received cash payments from the local CIA man and Western military attachés while Lumumba’s murder was being planned…With United States encouragement, Mobutu staged a coup in 1965 that made him the country’s dictator. And in that position he remained for more than thirty years…The United States gave him well over a billion dollars in civilian and military aid during the three decades of his rule. (302-303) This quotation demonstrates how imperative Western powers were in the placement of Mobutu’s absolute power. Without Western powers, he would not have had nearly as much financial support for his horrific actions. Once Washington supported Mobutu, he “became untouchable” (240). The United States expected a return in most of the money they threw into Zaire, but, of course, Mobutu had no intention of helping anyone but himself. Just like any other ruler with absolute power. Mobutu took absolute power to a level that even Leopold could not reach. Butcher describes Mobutu as, “an icon of modern African evil, an individual who did more than almost anyone to set the Congo and the wider region of central Africa on its downward spiral” (241). Butcher saw the remainder of Mobutu’s horror first hand during his visit to the Congo. He recalls Smith 9 a young man say, “This is a terrible place where terrible things happen. You really must leave before they find you” (236). This quote sums up the atrocities of the Congo, for they really were, at the most basic level, just plain terrible. And Mobutu is the one who left the Congo in this terrible state. The man Butcher quotes emphasizes that Butcher must leave before “they” find him. The “they” this man refers to are the infamous rebel groups that run rampant throughout the Eastern section of the Congo. Mobutu invited most of these Hutu-based rebel groups in the forests following the Rwandan genocide (13). These groups took complete advantage of the terrain, people, and wealth hidden in the Congo. With Mobutu’s help, they took it all and still remain in Eastern Congo to this day. His power was so drastic that it allowed his own country to be completely run over by another country. Just like King Leopold and Mr. Kurtz, Mobutu’s greatest strength was the ability to mask the atrocities happening directly under his rule to the rest of the world. Butcher claims, “There was a certain brilliance to Mobutu’s evil. He was the consummate showman, luring George Foreman and Muhammad Ali to his capital, Kinshasa, for the most famous bout in boxing history” (239). This famous match, which would come to be known as ‘Rumble in the Jungle,’ convinced the rest of the world that all activity in the Congo remained prosperous under Mobutu. He even dared to mutter the famous last words of Mr. Kurtz, “‘The horror! The Horror!’” when he saw “mutilated bodies” of Congolese people, as if he had never seen a dead Congolese man before (239). He had everyone fooled. The Mobutu scam ran until 1997, but this loss did not turn into a gain for the Congo. The Mobutu administration ran the country into the ground, as “most public services had ceased and the government had become, as it was under Leopold, merely a mechanism for the leader and his entourage to enrich themselves” (315). Mobutu’s initial precautions to strip the country of technology and return back to indigenous ways was mere evil Smith 10 genius. He advanced the country so far backwards that no one man or group of men would be smart enough to surpass the technologies that Mobutu allowed only himself and his military to indulge in. Absolute power had once again prevailed, which sent the country into a downward spiral, one that the country may never get out of. Mobutu could not have exploited Zaire without absolute power. Mr. Kurtz could not have taken advantage of the tribes around him without complete supremacy. King Leopold II could not have made billions of dollars without the advantage of unlimited authority. Each leader advanced the country farther and farther back in civilization with their corruption from power. Butcher describes this concept as “a country with more past than future, a place where the hands of the clock spin not forwards, but backwards” (249). Since the Congo has only moved backwards for the past 130 years, the only way the country can reverse their situation and make progress is by taking away their one disadvantage: a leader with complete control. The only way to move forward is to remove power from the people who are constantly moving the country backwards; the people who condone the silence. However, removing a corrupt leader from power cannot fix the entire problem. Butcher claims, “the people of Africa must share responsibility for showing themselves unable to change [the government]”. Unfortunately, “the people of Africa have not been capable of working together to rein in the excesses of dictators” (335). Since the people have not had a human rights leader to stand behind such as Nelson Mandela or Martin Luther King, we have not seen much change in the Congo. Today in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, there is a democracy led by President Joseph Kabila, yet the people have still not taken a stance. However, movement by the people is always very risky, which we saw throughout the Arab Spring. While Kabila has not proven to be as corrupt as Gaddafi or Mubarak, 1,200 people still die every single day due to disease, murder, plummeting Smith 11 birth rate, starvation, exposure, and exhaustion (Hochschild 226). Progress needs to be made internally by a multitude of people instead of slow development encouraged by only one president. Butcher asserts, “You solve Africa’s problems by creating a system of justice that actually works and by making leaders accountable for their actions” (325). Once the people create this system of justice, we can start to see positive, long-lasting change in the Congo. Absolute power in Western Africa can be stopped, but it is up to the people to determine how much longer they will let it stand in the way of their sovereignty. Smith 12 Works Cited Butcher, Tim. Blood River: A Journey to Africa's Broken Heart. New York: Grove, 2008. Print. Conrad, Joseph. Heart of Darkness: Authoritative Text, Backgrounds and Contexts, Criticism. Ed. Paul B. Armstrong. New York: W.W. Norton &, 2006. Print. Hochschild, Adam. King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998. Print.