Prematurity

advertisement

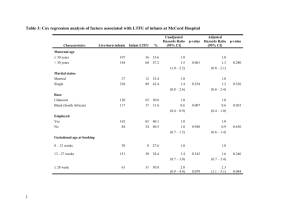

Prematurity Class Messinger Define prematurity. What factors predict the survival of premature infants How can prematurity be treated? What factors affect disability in the survivors? What types of disability and other outcomes are likely in survivors? How are mortality and morbidity rates of premature infants changing? If a baby is born 8 weeks premature, how long after birth would you conduct a 52 week assessment, after correcting for prematurity? How do socioeconomic status (maternal education) and prematurity to influence developmental outcome? What is the impact of variables such as maternal sensitivity on outcome – on which infants do they have the greatest impact? What interventions might improve the outcomes of premature infants (Kangaroo care, other types of physical contact) – please describe. How do you think public health policy should be structured to prevent negative developmental outcomes? What are the Fetal Origins of Adult Disease? Infant mortality rate (Ascending) The rate in the United States is 5.98, and there are 48 countries with lower rates, although many of those use a less stringent definition of mortality than the US http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_infant_mortality_rate Messinger Is mortality rate decreasing? Messinger Predicting prematurity Definition: 37 weeks gestational age or less Associated with low birthweight, > 2,500 g Incidence is linked to social risk and ethnicity – – socioeconomic status Ethnicity Messinger Norway Caucasian American African American 3 per 1,000 5.5 per 1,000 13.5 per 1,000 Premature infants differ in degree of prematurity, in related medical problems, and social risks Messinger More premature - reduced survival (survival rates increase over historical time) Weeks Gestation Survival 21 weeks 0% 22 weeks 0-10%* 23 weeks 10-35% 24 weeks 40-70% 25 weeks 50-80% 26 weeks 80-90% 27 weeks >90% 30 weeks >95% 34 weeks >98% Messinger A baby's chances for survival increases 3-4% per day between 23 and 24 weeks of gestation and about 2-3% per day between 24 and 26 weeks of gestation. After 26 weeks the rate of survival increases at a much slower rate because survival is high already. http://www2.medsch.wisc.edu/childrenshosp/parents_of_preemies/toc.html Survival Messinger The most important predictors greater gestational age heavier birth weight absence of severe breathing problems, congenital abnormalities, and other diseases like infections At a given age/weight Male infants are slightly less mature and have a slightly higher risk of dying than female infants. African-American babies have a slightly better survival than Caucasian – Messinger most other groups are intermediate between the two Significant disability Moderate or severe mental retardation, inability to walk without assistance, blindness or deafness More extreme prematurity is associated with greater risk of these conditions. Messinger At 23-24 weeks of gestation, risk is about 50%. As gestational age increases, the risk of significant disability declines dramatically. More developmental problems as birth weight decreases ELBW infants are more likely than higher birth weight infants to demonstrate mild (<85) to significant (<70) delays on the Mental Scales (MDI) and Psychomotor Scales (PDI) of the Bayley Scales (BSID-II) – 66% and 57% of ELBW children scored below the normative range on the MDI and PDI, respectively, at 18 to 22 months corrected age Poor performance on these measures may reflect early deficits in behavior regulation among ELBW infants including difficulty adapting to change, difficulty sustaining attention, increased activity level, increased need for examiner support and less persistence in attempting to complete tasks Messinger Shankaran, 2004; 5 Vohr, B.R. 2000; 6 Vohr, B.R. 2005; 3 Walsh, M.C. 2005 Anderson, P. 2003; 27 Leonard, C.H. 2001; 9 Saigal, S. 2001; 19 Sajaniemi, N. 2001; 26 Weiss, S.J. 2004; 10 Whitfield, M.F. 1997 ELBW infants at risk at 18 months 25% had an abnormal neurologic exam; 37% had a Bayley II Mental MDI <70; 29% had a Psychomotor PDI <70, 9% had vision & 11% had hearing impairment Increased morbidity: decreasing birth weight; lung disease; IVH 3-4 (brain hemorrhage), necrotizing enterocolitis Decreased morbidity: female gender, higher maternal education, and white race. • Messinger Vohr, B. R. et al., (2000). Neurodevelopmental and Functional Outcomes of Extremely Low Birth Weight Infants in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network, 1993-1994. Pediatrics, 105(6), 1216-1226. Big picture Continuous advances in medical technology mean that younger and lighter babies can be saved Does this mean an increase in the proportion of surviving infants who have disabilities? Messinger Survival improving—illness constant? Survival in infants 501-1500 g improved, 84% (1995-1996), 80% in 1991, 74% in 1988. Increased survival not associated with increased major morbidities 1991-1996 – CLD (chronic lung disease; 23%), proven NEC (7%), and severe ICH (11%)—did not change Mortality & major morbidity remain high for smallest: <600 g at birth. • Messinger Lemons, J. A., Bauer, C. R., et al. & Network, N. N. R. (2001). Very Low Birth Weight Outcomes of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network [14 participating centers], January 1995 Through December 1996. PEDIATRICS, 107(1), e1. Behavior predicts cognitive/motor development in ELBW children. 18 month Behavior Record Scale (BRS) 30 month MDI and PDI – Controlling for gender, birth weight, maternal income, maternal education, 18-month MDI and 18 month PDI, in identical models, 18 month BRS Motor Quality predicted both 30-month MDI and 30-month PDI. Messinger, Lambert, Bauer et al., 2010 What’s corrected age? If baby born 10 weeks early 52 weeks after birth – – – – comes 10 weeks early Only 30 weeks gestation Not 40 weeks So its 82 – not 92 – weeks of development after conception Solution: Correct (wait) 10 weeks – – Messinger Non-Premie Gives premies a chance to get on course Correct until 2 or 3 years 40 52 Gestation 52 weeks after birth Correction Premie 30 0 20 52 40 60 10 80 100 Predictors of disability Identifiable brain abnormalities such as more severe intraventricular hemorrhages (IVH) Messinger may occur before birth or in the nursery Babies who have been the sickest and/or remained sick for long periods of time (several weeks). APGAR (0 – 10) Each category summed – – – – – Appearance (0-2) Pulse (0-2) Grimace (0-2) Activity (0-2) Respiration (0-2) Add ‘em up 3 or below means baby in danger – Messinger so repeat APGAR every 5 minutes Prematurity in context Prematurity is a biological risk factor but outcome is also associated with social risk factors Messinger The effects of biological and social risk factors on special education placement: Birth weight and maternal education as an example Hollomon, H.A. Dobbins, D. R., & Skott, K.G. (1998). Research in Developmental Disabilities, 19(3), 281-294. Relative risk of special education by mom education & baby birth weight 4.5 4 3.5 3 2.5 2 1.5 4.19 3.17 2.65 2.08 1.53 2.07 2.05 1.54 1 1 0.5 0 > 12 y mom ed Messinger 12 y mom ed < 12 y mom ed NBW LBW VLBW Agree or disagree? Low Maternal Education associated with almost one fifth of the children in special education – – associated with the highest percentage of special education placements. approximately one third of the children were born to mothers who had less than 12 years of education. Messinger 22% of the sample had mothers with LME in the Metropolitan Atlanta Developmental Disabilities Study (Satcher, 1995). Less than 1% of children receiving special education services can be attributed to being VLBW because it is a low prevalence condition. Public policy: Target Low Maternal Education Policy: What’s the biggest population risk? Messinger Theoretical Framework -Ecological models (e.g. Bronfenbrenner model) Social Interaction Quality -Preterm infants showed limited amount and poorer quality of Interactions with parents • Maternal factors -Less interactive Gestational age Birth weight -SES Physiological regulation (HRV) -Feeding route Infant factors – – – Romero 4 Month Results Positive affect, Social, and Communicative Competence: – Higher vagal regulation less positive affect & communication at 4 months – – Fewer SES risks more optimal interactions at 4 months. More neonatal health risks showed more positive affect at 4 months. Quality of Play, Interest, and Attention: – – but showed greater increases over time exceed those infants with lower vagal regulation. Infants born closer to term were higher on this subscale at 4 months. More SES risks poorer quality of this subscale at 4 months. Dysregulation and Irritability: – Higher vagal regulation implied less dysregulation and irritability. Romero Messinger Interventions for the premature infant: Kangaroo Care (KC) ‘Holding a diaper-clad infant in skin-to-skin contact, prone and upright on the chest of the parent. Subsequent text from http://www.adhb.govt.nz/newborn/guidelines/developmental/KangarooCare.htm Initiated after acute risk has passed Developing and developed world? Messinger http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gQwdlMnkhbA&feature=related http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5yl-prEacIM&feature=related daddy Wrap Instructions: Kangaroo Care with a Wrap Administer Kangaroo Care to medically stable infants Messinger Exclusion Criteria First 5 days for infants less than 30 weeks gestation… Unstable on respiratory support (CPAP or ventilation) After major procedures or treatment e.g extubation Reported Benefits of Kangaroo Care Decreased variation in heart and respiratory rates, improved oxygenation, less bradycardia… Maintains skin and core temperatures through conduction of heat from the parent. Promotes optimal growth and development. Beneficial for sleep-wake organisation. Increases mother’s milk production unlimited access to breast. Messinger Sample study Reduction hypothermia (10/44 vs 21/45) higher oxygen saturations (95.7 vs 94.8) decrease in respiratory rates (36.2 vs 40.7) No differences in hyperthermia, sepsis, apnea, onset of breastfeeding and hospital stay in two groups. Randomized controlled trial was performed over one year: kangaroo mother care (KMC) vs. conventional • Messinger 1: Indian J Pediatr. 2005 Jan;72(1):35-8. Feasibility of kangaroo mother care in Mumbai.Kadam S, Binoy S, Kanbur W, Mondkar JA, Fernandez A. Family involvement, massage therapy Messinger “Massage therapy has been notably effective in preventing prematurity, enhancing growth of infants, increasing attentiveness, decreasing depression and aggression, alleviating motor problems, reducing pain, and enhancing immune function. “ Massage therapy research.Field, Tiffany; Diego, Miguel; Hernandez-Reif, Maria. Developmental Review. Vol 27(1), Mar 2007, 75-89. Sensitive parenting helps children at highest medical risk Parenting (6 & 12 months) that was sensitive to children's focus of interest and not highly controlling or restrictive predicted Greater increases & faster rates of cognitive-language & social development @ 6, 12, 24, 40 mos. – Relations stronger for high risk (HR; n = 73) – Messinger Vs. full-term n=112 & medically low risk but low birth weight, n=114 Sensitive behaviors may provide support HR children need to learn in spite of early attentional and organizational problems. – Confounds? – Landry, S. H., Smith, K. E., Miller-Loncar, C. L., & Swank, P. R. (1997). Predicting cognitive-language and social growth curves from early maternal behaviors in children at varying degrees of biological risk. Developmental Psychology, 33(6), 1040-1053. Mom maintaining vs. restrictiveness Landry et al., 1997 Messinger For both LBW & NBW ‘Mothers' maintaining children's interests supported 2- & 3½-yr skills 4½-yr cognitive and social independence – Directiveness supported children's early cognitive and responsiveness skills High levels of maintaining interests across these ages support later independence, – Messinger but by 3½ yrs, high levels of this behavior had a negative influence on cognitive and social independence at 4½ yrs. but directiveness needs to decrease in relation to children's increasing competencies.’ Landry, S. H., Smith, K. E., Swank, P. R., & Miller-Loncar, C. L. (2000). Early maternal and child influences on children's later independent cognitive and social functioning. Child Development, 71, 358-375. Responsive Parenting: Establishing Early Foundations for Social, Communication, and Independent Problem-Solving Skills (Landry, Swift, & Swank, 2006) Responsive parenting: – – – – Contingent responding Emotional-affective support Support for infant foci of attention Language input that supports developmental needs Intervention: PALS (Playing and Learning Strategies) v. DAS (Developmental Assessment Screening) – 263 infants, 10 home visits between 6-10 months of age – Mothers reviewed weekly experience, visitor described purpose of visit, discussed educational videotapes, videotaped mothers, mothers critiqued own behavior, discussed responsive strategies Infants were videotaped and assessed at each visit – Nayfeld Influence of responsive parenting on infant behavior: Intervention Increases in mother’s responsive behaviorsincrease in infant skills in first year – – Responsiveness in all aspects improved more in target mothers Greater changes in infant behaviors (cooperation, use of words, affect, problem solving) in PALS Both with mother and novel adult Responsiveness mediates impact on infant development – – General responsiveness construct, with 4 distinct factors Contingent responsiveness, verbal encouragement, and restrictiveness are mediators Fully mediated relationship intervention became non-significant Nayfeld Catch-up facilitated by more optimal social environment Brain plasticity – Median PPVT-R increased from 88 (36 months) to 99 at (96 months) in 296 VLBW infants (600 to 1250 g) 45% of children gained 10 points or more – Increasing age, 2-parent household, higher levels of maternal education all associated with higher scores • – Messinger children with early-onset IVH and subsequent CNS injury had lowest initial scores & the scores declined over time (interaction). Change in cognitive function over time in very low-birth-weight [VLBW] infants (Ment et al, 2003, JAMA, 289, 705-71 Long-term outcome: Educational disadvantage but lower risk-taking Very-low-birth-weight infants as young adults Fewer VLBW adults graduate hi school: 74% vs 83% VLBW men, but not women, significantly less likely than controls to be in postsecondary study (30% vs. 53%, P=0.002). VLBW lower IQ (87 vs 92) & academic achievement 242 VLBWs born ‘77-79 (at 1179 g) vs 233 normal birth weight Higher rates of neurosensory impairments (10% vs. <1%) and subnormal height (10% vs. 5%, P=0.04). VLBW group reported less alcohol & drug use & lower rates of pregnancy – differences exist in those without neurosensory impairment. Messinger Hack, M., Flannery, D. J., Schluchter, M., Cartar, L., Borawski, E., & Klein, N. (2002). Outcomes in Young Adulthood for VLBW Infants. New England Journal of Medicine, 346(3), 149-157. Why? The fetal origins of adult disease “David Barker pioneered the idea that the 20th century epidemic of coronary heart disease in Western countries might have originated in fetal life.1Paradoxically, the epidemic coincided with improved standards of living and nutrition, yet in Britain its greatest impact was in the most deprived areas. Barker observed that early in the 20th century these areas had the highest rates of neonatal mortality and by inference the highest rates of low birth weight. He postulated that impaired fetal growth might have predisposed the survivors to heart disease in later life.” – Messinger BMJ 2001;322:375-376 ( 17 February ) Fetal Origins of Adult Disease: Concepts and Controversies Association of low birthweight with increased risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes. – controlling for lifestyle factors such as smoking, physical activity, occupation, income, dietary habits, and childhood socioeconomic status. • NeoReviews Vol.5 No.12 2004 e511 © 2004 American Academy of Pediatrics. Rebecca Simmons* Infants are compensating for earlier weight loss in a way that does not bode well longterm Messinger Mechanism of effects? Combination of small size at birth and during infancy, followed by accelerated weight gain from age 3 to 11 years, predicts large differences in CHD, type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Mechanisms: developmental plasticity and compensatory growth. – Messinger Int J Epidemiol. 2002 Dec;31(6):1235-9. Links. Fetal origins of adult disease: strength of effects and biological basis. Barker DJ, Eriksson JG, Forsén T, Osmond C. Additional readings Messinger Messinger, D., Dolcourt, J., King, J., Bodnar, A., & Beck, D. (1996). The survival and developmental outcome of extremely low birthweight infants. Infant Mental Health Journal, 17(4), 375-385. Hollomon, H.A. Dobbins, D. R., & Skott, K.G. (1998). The effects of biological and social risk factors on special education placement: Birth weight and maternal education as an example. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 19(3), 281-294. Infant Health and Development Project (1990). Enhancing the outcomes of low-birth-weight, premature infants: A multisite, randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 263(22), 3035-3042. Brooks-Gunn, J., McCarton, C., McCormick, M. C., & Klebanov, P. K. (1998). The contribution of neighborhood and family income to developmental test scores over the first three years of life. Child Development, 69(5), 1420-1436. Vohr, B. R., Wright, L. L., Dusick, A. M., Mele, L., Verter, J., Steichen, J. J., Simon, N. P., Wilson, D. C., Broyles, S., Bauer, C. R., Delaney-Black, V., Yolton, K. A., Fleisher, B. E., Papile, L.-A., & Kaplan, M. D. (2000). Neurodevelopmental and Functional Outcomes of Extremely Low Birth Weight Infants in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network, 1993-1994. Pediatrics, 105(6), 1216-1226. Susan Landry, Developmental Psychology. Zeanah, C. on developmental risk. J am acad child and adol psychiatry '97 362. Review Syllabus Messinger Syllabus