work session 7 crean presention on takings and contract zoning

advertisement

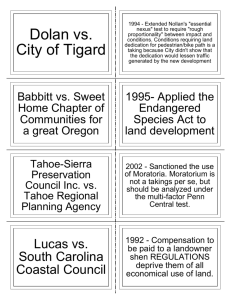

June 22, 2012 Work Session 7 Development Conditions – Overview and Issues Exactions & Takings Contract Zoning Daniel D. Crean, Pembroke, New Hampshire IMLA CLE SEMINAR Guidance from Federal Decisions Note: Portions of this presentation derived from one made for a NHMLA CLE seminar held June 30, 2010 Takings and exactions with an eye toward application in the context of development conditions Contract v. Conditional Zoning 3 4 Source of Takings Law: ◦ 5th Amdt applied to states (& local govt) by 14th Substantive Due Process & Equal Protection and Due Process Constitutional principles also apply and have been sources of confusion in defining takings. State Constitutional requirements may differ. What is “property” that can be taken? ◦ May differ from takings under state law. ◦ Still in flux as discussed later. 5 Physical invasion and actual appropriation in earliest cases evolved to interference with use of property rights in broad sense (property rights as a bundle – e.g., right to exclude). Mere devaluation in value does not mean a taking occurs (e.g., Euclid v. Ambler Realty). But, in Penn Coal, taking occurs when regulation “goes too far”! 6 7 Some 50 years later, federal courts began to seek definition of Holmes’ statement: ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Whole parcel rule – Penn Central Takings “2-step” – Agins Remedy – Compensation or not – San Diego Physical Invasion revisited – Loretto 1987 Trilogy ◦ Bundle of rights, property definition, investment-backed expectations & a new test “Going too far” revisited - Keystone Compensation for a temporary taking – 1st English Rational Nexus - Nollan 8 Judicial Activism & Property Protections??? ◦ Per se takings – economic wipeouts – Lucas Development of more vocal dissents Getting to court is half the battle or more . . . ◦ Ripeness – Final Decision – State Remedy ◦ Williamson County, Yee, & Palazzolo Property rights and regulations existing at time of taking title ◦ Palazzolo, again Moratoria – a moratorium on takings? ◦ Tahoe-Sierra 9 Redefinition & replacement ◦ Sharpening focus, SCOTUS (now) appears to recognize that SDP and Takings are not the same! ◦ Did so in a case that was not a land use case (Lingle) ◦ Revert to Penn Central analysis – effect on parcel as whole – what goes into numerator and denominator that is so “onerous that its effect is tantamount to a direct appropriation or ouster” of property rights Side notes ◦ Who’s got the ball? – choosing the forum – San Remo ◦ Eminent domain – Kelo and the Kelo backlash 10 Supreme Court doctrine and dicta that will likely be fleshed out and clarified in future decisions may include (see paper): ◦ Ripeness and exhaustion v. res judicata effect ◦ Investment-backed expectations v. regulation enacted after property acquisition v. background principles of state property law ◦ Limitation on full property use ◦ Functional appropriation of property rights ◦ Judicial decisions as takings ◦ Rational Nexus/Rough Proportionality applied 11 Property rights – and full usage ◦ Casitas Diminution in use of property need not be total Not a U.S. Supreme Court ruling How much compensation is enough? ◦ Rose Acre Farms Lost Profits & Economic Impact “Mere” 10% loss is slight and temporary Also not a SCOTUS decision 12 Stop the Beach Renourishment ◦ Is a property right taken? Deference to state law definitions of property Consistent w. Penn Coal, Keystone, even Lucas ?? Orientation toward purpose and result Benefit-conferring or harm-preventing Acquisitive intent or not Expectations of owners under state property rights law ◦ Is there such a thing as a judicial taking and did it occur by Florida Supreme Court’s ruling? Not answered, but three or perhaps four justices said there appears to be such a taking. 13 Exaction = requirement to do something or not do something as a condition of obtaining a land use approval. ◦ May involve physically doing something; ◦ May involve paying for doing something; ◦ May involve not doing something (e.g., lesser level of development, land in open space, etc.); ◦ May involve “donating” land – dedications; ◦ May involve one or more of above or even something else. 14 Exactions are neither per se valid or invalid. Tests used to assess their validity have varied from stringent (specifically and directly attributable) to liberal (but/for). Exactions are designed to offset impacts on development: ◦ Are not designed to raise revenue (not taxes) Key factors, then, even before recent rulings included: ◦ Relationship to development? ◦ How much is too much? 15 State law tests will vary – subject to overriding requirement of meeting federal property protection requirements - ◦ For example, NH rational nexus test under Land/Vest seemingly still applies. Federal Base Line set by Nollan and Dolan ◦ Rational nexus (Nollan) neither remarkable nor overly stringent – look at (1) why property is asked for exaction and (2) what does exaction have to do with the actions proposed? ◦ Rough Proportionality (Dolan) – some numerical basis for amount of exaction required – need not be mathematically precise. 16 A selective list of what has occurred recently includes ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Quantifying rough proportionality – B.A.M. Development Affordable housing – state mandates – Palmer, et al. Enabling legislation & limits – N.J. Shore Builders Assn. Cost analysis – McLung Tapps Brewing Revising assessments – Building Assn. v. Patterson Analysis of decisions such as those listed above will be key in responding to Nollan, and particularly Dolan, challenges. Ability to demonstrate “why” and “how much” will be essential to defense. 17 Clare v. Hudson – also discussed in W.S. 8 ◦ Not the first time that NH Supreme Court has misunderstood or at least misapplied (in my view) exactions: Conceptually, and legally, exactions imposed administratively are different from impact fees. Bottom line, though, requires that municipality demonstrate that rational nexus and rough proportionality are met, no matter whether imposed via exaction or impact fee. Keys to take from decision ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Do homework to justify Don’t forget the paper work and recordkeeping Keep a tickler file Use a developer agreement 18 Hopefully these are more useful than these directional arrows Start with examining enabling legislation & court decisions What authority can and should be used What public needs or impacts are involved (qualitative – rational relationship analysis) What are costs of current and future needs (quantitative and relative – proportional analysis) When burden/needs exceed fees otherwise paid (including tax revenue considerations), what exactions may be appropriate What level of exaction does NOT impose disproportionate burden 19 Much has been written and said about Dolan’s mention of rough proportionality in the context of an adjudicative decision (i.e., by a land use board on a particular application). The distinction has caused courts and commentators to examine concepts such as: ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Legislative deference – applied or not Motivation of ordinance When does heightened scrutiny apply How does it get applied in context 20 From a constitutional perspective, particularly under Lingle, the question of when an exaction may violate rational nexus or rough proportionality need not depend on whether local government is acting legislatively or adjudicatively (aka administratively or quasi-judicially). Real issue and question to be examined is the extent to which the burden shifted to the property owner – however shifted – is disproportionate to the burdens that should be borne. 21 In some respects, the foregoing analysis may be bringing us back full circle to Penn Coal. The evolution of both takings and exactions law, however, has somewhat sharpened the focus of how local governments may and must allocate burdens that seek to accommodate development of property. The municipal burden of justifying ordinances and decisions is not onerous but requires understanding and demonstration of supportable base for decision. 22 Contract Zoning Archaic Idea or Constraint on Conditions 23 Contract zoning as a “term of art” may be viewed as archaic and something reserved for the hallowed halls of academia. Although perhaps more honored in concept than application in court, rezoning premised upon performance of conditions may raise concerns. 24 One definition: ◦ Contract Zoning is an agreement between a property owner and a zoning authority, which binds the property owner to special restrictions on the use of the property and, in turn, binds the local zoning authority to grant the rezoning. In and of itself, it is not necessarily “Invalid.” Concerns may arise when: ◦ It constitutes an exercise of the police power for reasons other than the usual public purpose standard; and ◦ Conditions are not met. 25 “contract made by a zoning authority to zone or rezone or not to zone is illegal and the ordinance is void because a municipality may not surrender its governmental powers and functions or thus inhibit the exercise of its police or legislative powers.” State ex rel. Zupancic v. Schimenz, 46 Wis.2d 22, 174 N.W.2d 533 (1970). 26 May be similar in some instances to issues associated with identifying improper spot zoning (e.g., not in conformity with Master Plan) Lack of enabling authority for conditional or flexible zoning (ultra vires) Contractual relationship outside of zoning power 27 If conditions are not met, does that invalidate the zoning? ◦ What about after development started? What is effect of “return to status prior to rezoning”? If contract zoning (by whatever name) is found to be invalid, what is the remedy? ◦ Invalidate conditions ◦ Invalidate rezoning ◦ Impeach the planning board/commission and legislative body ◦ And don’t forget the lawyers who set up the whole deal! 28 Keep public purpose foremost in studies, findings, and wording ◦ WORDS DO MATTER Tie conditions (performance of developer obligations to a public purpose or use – other than “show me the money!” 29 MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING But YOU BE THE JUDGE! 30 Questions, Comments, Concerns Contact: Attorney Daniel Crean Crean Law Office Pembroke, NH 03275 928-7760 creanlaw@comcast.net www.creanlaw.com 31