Robinson Crusoe & The Establishment of Unequal Wealth and

advertisement

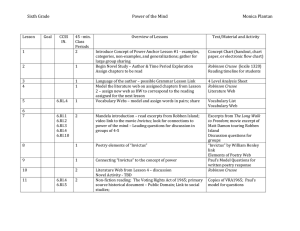

Robinson Crusoe & The Establishment of Unequal Wealth and Tourism Jenna Sheeran Thesis The foundations that allow some to be tourists and some to be too poor to leave their “native” countries can be traced back to the colonial practices of obtaining wealth more or less easily from the natural and human resources on the Caribbean. I will explore how the mobility of European colonists fueled such a drastic economic inequality that has persisted into modern times by using ideas from Mimi Sheller and Stephen Hymer in regards to the economics of colonialism. By doing so, it should become clear that tourism is not just a way for Caribbean islands to generate revenue, but that it is a continuation of colonial ideas in that it still disadvantages the Caribbean from both an economic and an ethical standpoint. How Economic Inequality was Established “Robinson Crusoe and the Secret of Primitive Accumulation” Stephen Hymer: Canadian Economist Examines how Crusoe develops his wealth in a book called Robinson Crusoe’s Economic Man “Once capitalism is on its legs, it maintains this separation and reproduces it on a continuously expanding scale. But a prior stage is needed to clear the way for the capitalist system and get it started – a period of primitive accumulation” (Hymer) Stephen Hymer’s Cycles of Economic Control M-C-M (Money-Commodity-Money): “[Crusoe] starts off with money, exchanges it for commodities and ends up with more money” Huge investment return because of mobility: “…this voyage made me both a sailor and a merchant; for I brought home five pounds nine ounces of gold-dust for my adventure, which yielded me in London, at my return, almost 300 pounds…” (Defoe 10). the items he traded were only worth 40 pounds Stephen Hymer’s Cycles of Economic Control C-L-C (Commodity-Labor-Commodity): “[Crusoe] uses his stock of commodities to gain control over other people’s labor and to produce more commodities, ending up with a small empire” Crusoe uses the natural resources of the island (which he possesses for free) as a means of providing for the individuals that come upon the island, and thus is able to control them and use their labor to produce goods that allow for his escape. Friday’s servitude English Captain’s debt for his life Economic Continuities Between Colonialism & Tourism Economic Control Cycles & Tourism Referenced in A Small Place Kincaid satires how Westerners perceive themselves to have become wealthy based on their own merits: “…the West got rich not from the free (free-in this case meaning got-fornothing) and then undervalued labour, for generations, of the people like me you see walking around you in Antigua but from the ingenuity of small shopkeepers in Sheffield and Yorkshire and Lancashire…” (Kincaid Loc 77). Position of the tourist made possible by “superiority” of ancestors: “…and since you are being an ugly person this ugly but joyful thought will swell inside you: their ancestors were not clever in the way yours were and not ruthless in the way yours were, for then would it not be you who would be in harmony with nature and backwards in the charming way?” (Kincaid Loc 143). Post-Colonial Economic Inequality in A Small Place Superior/inferior: “Every native would like to find a way out, every native would like a rest, every native would like a tour. But some natives-most natives in the world-cannot go anywhere. They are too poor. They are too poor to go anywhere…and they are too poor to live properly in the place where they live…” (Kincaid Loc 157). Inferior status as a source of joy for the superior: “[The natives] envy your ability to turn their own banality and boredom into a source of pleasure for yourself” (Kincaid Loc 163). The Caribbean Garden of EdenMarketing the Caribbean “In this part I found melons upon the ground, in great abundance, and grapes upon the trees. The vines had spread, indeed, over the trees, and the clusters of grapes were just now in their prime, very ripe and rich” (Defoe 63). “[The Caribbean] is represented as a perpetual Garden of Eden in which visitors can indulge all their desires and find a haven for relaxation, rejuvenation, and sensuous abandon (Sheller 13). Tourism & Bargaining Continuing with the idea that the Caribbean is a Garden of Eden for tourists, bargaining is a practice that develops from the thinking that one is entitled to the goods and productions of the Caribbean. In a more modern sense, the practice of bargaining is similar to the idea that the Caribbean is a place where goods can be attained for nothing or almost nothing, which is what happens when tourists use both the exchange rate and the destitute economic conditions of local sellers to their advantage. There are various blogs and tourism resources that instruct prospective tourists how to bargain for items in tourist destinations. Most of these sources say that bargaining is something that will typically always work, and that tourists can expect to be able to haggle sellers to sell their product(s) for 15-50% less than the original price. This is a small but relevant example of how tourism utilizes the elevated economic status of the tourist in inferior host nations. The sellers are forced to submit to bargaining because their only market is to sell to tourists, showing that once the divides between economically superior and inferior are established, they are reproduced and expanded upon. Robinson Crusoe Styled Getaways The nostalgia of colonial control and individual wealth is clearly still attractive to tourists, as many destinations offer tourism packages that are modeled after Defoe’s novel. The idea of possession and nostalgia is appealed to in the marketing of an untouched space: “Tobago is home to the oldest protected rainforest in the Western Hemisphere. It really is the last of the unspoilt Caribbean. Once you behold her beauty, you will understand why Tobago was Robinson Crusoe's isle and why our European settlers fought over her ownership more than any other Caribbean island” (Trinidad and Tobago Tourism). Images From Robinson Crusoe Tourist Ads There are clear connections between the economic practices of colonialism and those of tourism, suggesting that the ideas of colonialism did not really end, but are instead manifested in the dynamics of tourism, which is merely a new way of occupying and controlling the Caribbean. Takaha White’s post on Art With A Message Instagram Account References Works Cited Defoe, Daniel. Robinson Crusoe. Philadelphia: G.W. Jacobs, 1913. Print. Hymer, Stephen. "Robinson Crusoe's Economic Man." Google Books. Routledge Frontiers of Political Economy, n.d. Web. 23 Jan. 2015. <http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=89GoAgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA42&dq=robinson%2Bcrusoe %2Band%2Bwealth&ots=NFo06mzM6Z&sig=hqTeUgvJxepsw351lwSmRiISM84#v=onepage&q=robinson%20crus oe%20and%20wealth&f=false>. Kincaid, Jamaica. A Small Place. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1988. Print. Nanton, P. "Consuming the Caribbean: From Arawaks to Zombies. By Mimi Sheller (Routledge 2003. Ix plus 252 Pp.)." Journal of Social History 39.4 (2006): 1205-206. Web. "Robinson Crusoe Style Tourism in Croatia." Robinson Crusoe Style Accommodation for Your Summer Vacation in Croatia. Adriatic.hr, n.d. Web. 22 Jan. 2015. <http://www.adriatic.hr/en/robinson-tourism>. "Trinidad & Tobago Tourism." Trinidad & Tobago Tourism. N.p., n.d. Web. 25 Jan. 2015. <http://amgltd.biz/clientsDetail.php?Trinidad-Tobago-Tourism-29>. "Vientiane Forum." Bartering. N.p., n.d. Web. 23 Jan. 2015. <http://www.tripadvisor.com/ShowTopic-g293950i11502-k4273944-Bartering-Vientiane_Vientiane_Province.html>.