Natural selection

1

1

Populations

•

A group of the

• same species living in an area

No two individuals

• are exactly alike

(variations)

More Fit individuals survive & pass on their traits

2

2

Species

•

Different species

• do NOT exchange genes by interbreeding

Different species that interbreed often produce sterile or less viable offspring e.g. Mule

3

3

Speciation

•

Formation of new

• species

One species may

• split into 2 or more species

A species may

• evolve into a new species

Requires very periods of time long

4

4

Modern

Evolutionary

Thought

5

Modern Synthesis Theory

•

•

Combines Darwinian selection and

Mendelian inheritance

Population genetics study of genetic variation within a population

•

Emphasis on quantitative characters

6

6

Modern Synthesis Theory

•

• Today’s theory on evolution

Recognizes that GENES are responsible

• for the inheritance of characteristics

Recognizes that POPULATIONS , not

• individuals, evolve due to natural selection & genetic drift

Recognizes that SPECIATION usually is due to the gradual accumulation of small genetic changes

7

7

Microevolution

•

Changes occur in gene pools due to

• mutation, natural selection, genetic drift, etc.

Gene pool changes cause more

•

•

VARIATION in individuals in the population

This process is called

MICROEVOLUTION

Example: Bacteria becoming unaffected by antibiotics (resistant)

8

8

The Gene Pool

•

Members of a species can interbreed & produce fertile offspring

•

•

Species have a shared gene pool

Gene pool – all of the alleles of all individuals in a population

9

9

Allele Frequencies Define Gene Pools

500 flowering plants

480 red flowers 20 white flowers

320 RR 160 Rr 20 rr

As there are 1000 copies of the genes for color, the allele frequencies are (in both males and females):

320 x 2 (RR) + 160 x 1 (Rr) = 800 R; 800/1000 = 0.8

(80%) R

160 x 1 (Rr) + 20 x 2 (rr) = 200 r; 200/1000 = 0.2

(20%) r

10

10

Gene Pools

•

A population’s gene pool is the total of all genes in the population at any one time.

•

Each allele occurs with a certain frequency (.01 – 1) .

11

11

The Hardy-Weinberg Theorem

•

Used to describe a non-evolving

•

population.

Shuffling of alleles by meiosis and

•

random fertilization have no effect on the overall gene pool.

Natural populations are NOT expected to actually be in Hardy-

Weinberg equilibrium

.

12

12

The Hardy-Weinberg Theorem

•

•

Deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium usually results in evolution

Understanding a non-evolving population, helps us to understand how evolution occurs

13

13

Sources of genetic variation

(Disruption of H-W law)

1. Mutations

- if alleles change from one to another, this will change the frequency of those alleles

2. Genetic recombination

- crossing over; independent assortment

3. Migration

- immigrants can change the frequency of an allele by bringing in new alleles to a population.

- emigrants can change allele frequencies by taking alleles out of the population

14

14

Sources of genetic variation

(Disruption of H-W law)

4. Genetic Drift

small populations can have chance fluctuations in allele frequencies (e.g., fire, storm).

bottleneck; founder effect

5. Natural selection

if some individuals survive and reproduce at a higher rate than others, then their offspring will carry those genes and the frequency will change for the next generation.

15

15

Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium

The gene pool of a non-evolving population remains constant over multiple generations; i.e., the allele frequency does not change over generations of time.

The Hardy-Weinberg Equation:

1.0 = p 2 + 2pq + q 2 where p 2 = frequency of AA genotype; 2pq = frequency of

Aa plus aA genotype; q 2 = frequency of aa genotype

16

16

17

17

18

18

But we know that evolution does occur within populations.

Evolution within a species/population = microevolution.

Microevolution refers to changes in allele frequencies in a gene pool from generation to generation. Represents a gradual change in a population.

Causes of microevolution:

1) Genetic drift

2) Natural selection (1 & 2 are most important)

3) Gene flow

4) Mutation

19

19

1) Genetic drift

Genetic drift = the alteration of the gene pool of a small population due to chance.

Two factors may cause genetic drift: a) Bottleneck effect may lead to reduced genetic variability following some large disturbance that removes a large portion of the population. The surviving population often does not represent the allele frequency in the original population.

b) Founder effect may lead to reduced variability when a few individuals from a large population colonize an isolated habitat.

20

20

21

21

22

22

*Yes, I realize that this is not really a cheetah.

23

23

2) Natural selection

As previously stated, differential success in reproduction based on heritable traits results in selected alleles being passed to relatively more offspring (Darwinian inheritance).

The only agent that results in adaptation to environment.

3) Gene flow

-is genetic exchange due to the migration of fertile individuals or gametes between populations.

24

24

25

25

4) Mutation

Mutation is a change in an organism’s DNA and is represented by changing alleles.

Mutations can be transmitted in gametes to offspring, and immediately affect the composition of the gene pool.

The original source of variation.

26

26

Genetic Variation, the Substrate for Natural Selection

Genetic (heritable) variation within and between populations: exists both as what we can see (e.g., eye color) and what we cannot see (e.g., blood type).

Not all variation is heritable.

Environment also can alter an individual’s phenotype [e.g., the hydrangea we saw before, and…

…Map butterflies (color changes are due to seasonal difference in hormones)].

27

27

28

28

Variation within populations

Most variations occur as quantitative characters (e.g., height); i.e., variation along a continuum, usually indicating polygenic inheritance.

Few variations are discrete (e.g., red vs. white flower color).

Polymorphism is the existence of two or more forms of a character, in high frequencies, within a population. Applies only to discrete characters.

29

29

Variation between populations

Geographic variations are differences between gene pools due to differences in environmental factors.

Natural selection may contribute to geographic variation.

It often occurs when populations are located in different areas, but may also occur in populations with isolated individuals.

30

30

Geographic variation between isolated populations of house mice.

Normally house mice are

2n = 40. However, chromosomes fused in the mice in the example, so that the diploid number has gone down.

31

31

Cline, a type of geographic variation, is a graded variation in individuals that correspond to gradual changes in the environment.

Example: Body size of North American birds tends to increase with increasing latitude. Can you think of a reason for the birds to evolve differently?

Example: Height variation in yarrow along an altitudinal gradient. Can you think of a reason for the plants to evolve differently?

32

32

33

33

Mutation and sexual recombination generate genetic variation a. New alleles originate only by mutations (heritable only in gametes; many kinds of mutations; mutations in functional gene products most important).

- In stable environments, mutations often result in little or no benefit to an organism, or are often harmful.

- Mutations are more beneficial (rare) in changing environments. (Example: HIV resistance to antiviral drugs.) b. Sexual recombination is the source of most genetic differences between individuals in a population.

- Vast numbers of recombination possibilities result in varying genetic make-up.

34

34

Diploidy and balanced polymorphism preserve variation a. Diploidy often hides genetic variation from selection in the form of recessive alleles.

Dominant alleles “hide” recessive alleles in heterozygotes.

b. Balanced polymorphism is the ability of natural selection to maintain stable frequencies of at least two phenotypes.

Heterozygote advantage is one example of a balanced polymorphism, where the heterozygote has greater survival and reproductive success than either homozygote

(Example: Sickle cell anemia where heterozygotes are resistant to malaria).

35

35

36

36

Frequency-dependent selection = survival of one phenotype declines if that form becomes too common.

(Example: Parasite-Host relationship. Co-evolution occurs, so that if the host becomes resistant, the parasite changes to infect the new host. Over the time, the resistant phenotype declines and a new resistant phenotype emerges.)

37

37

38

38

39

39

Neutral variation is genetic variation that results in no competitive advantage to any individual.

- Example: human fingerprints.

40

40

A Closer Look: Natural Selection as the Mechanism of

Adaptive Evolution

Evolutionary fitness - Not direct competition, but instead the difference in reproductive success that is due to many variables.

Natural Selection can be defined in two ways: a. Darwinian fitness- Contribution of an individual to the gene pool, relative to the contributions of other individuals.

And,

41

41

b. Relative fitness

- Contribution of a genotype to the next generation, compared to the contributions of alternative genotypes for the same locus.

- Survival doesn’t necessarily increase relative fitness; relative fitness is zero (0) for a sterile plant or animal.

Three ways (modes of selection) in which natural selection can affect the contribution that a genotype makes to the next generation. a. Directional selection favors individuals at one end of the phenotypic range. Most common during times of environmental change or when moving to new habitats.

42

42

Directional selection

43

43

Diversifying selection favors extreme over intermediate phenotypes.

- Occurs when environmental change favors an extreme phenotype.

Stabilizing selection favors intermediate over extreme phenotypes.

- Reduces variation and maintains the current average.

- Example = human birth weights.

44

44

Diversifying selection

45

45

46

46

Natural selection maintains sexual reproduction

-Sex generates genetic variation during meiosis and fertilization.

-Generation-to-generation variation may be of greatest importance to the continuation of sexual reproduction.

-Disadvantages to using sexual reproduction: Asexual reproduction produces many more offspring.

-The variation produced during meiosis greatly outweighs this disadvantage, so sexual reproduction is here to stay.

47

47

All asexual individuals are female (blue). With sex, offspring = half female/half male. Because males don’t reproduce, the overall output is lower for sexual reproduction.

48

48

Sexual selection leads to differences between sexes a. Sexual dimorphism is the difference in appearance between males and females of a species.

-Intrasexual selection is the direct competition between members of the same sex for mates of the opposite sex.

-This gives rise to males most often having secondary sexual equipment such as antlers that are used in competing for females.

-In intersexual selection (mate choice), one sex is choosy when selecting a mate of the opposite sex.

-This gives rise to often amazingly sophisticated secondary sexual characteristics; e.g., peacock feathers.

49

49

50

50

51

51

Natural selection does not produce perfect organisms a. Evolution is limited by historical constraints (e.g., humans have back problems because our ancestors were 4-legged). b. Adaptations are compromises. (Humans are athletic due to flexible limbs, which often dislocate or suffer torn ligaments.) c. Not all evolution is adaptive. Chance probably plays a huge role in evolution and not all changes are for the best.

d. Selection edits existing variations. New alleles cannot arise as needed, but most develop from what already is present.

52

52

Genes Within

Populations

Chapter 21

53

Gene Variation is Raw Material

Natural selection and evolutionary change

Some individuals in a population possess certain inherited characteristics that play a role in producing more surviving offspring than individuals without those characteristics.

The population gradually includes more individuals with advantageous characteristics.

54

54

Gene Variation In Nature

Measuring levels of genetic variation blood groups – 30 blood grp genes

Enzymes – 5% heterozygous

Enzyme polymorphism

A locus with more variation than can be explained by mutation is termed polymorphic .

Natural populations tend to have more polymorphic loci than can be accounted for by mutation.

15% Drosophila

5-8% in vertebrates

55

55

Hardy-Weinberg Principle

Population genetics - study of properties of genes in populations blending inheritance phenotypically intermediate (phenotypic inheritance) was widely accepted new genetic variants would quickly be diluted

56

56

Hardy-Weinberg Principle

Hardy-Weinberg - original proportions of genotypes in a population will remain constant from generation to generation

Sexual reproduction (meiosis and fertilization) alone will not change allelic (genotypic) proportions.

57

57

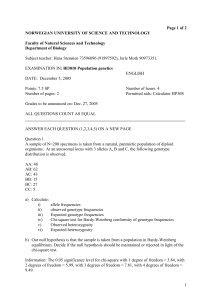

Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium

Population of cats n=100

16 white and 84 black bb = white

B_ = black

Can we figure out the allelic frequencies of individuals BB and Bb?

58

58

Hardy-Weinberg Principle

Necessary assumptions

Allelic frequencies would remain constant if… population size is very large random mating no mutation no gene input from external sources no selection occurring

59

59

Hardy-Weinberg Principle

Calculate genotype frequencies with a binomial expansion

(p+q) 2 = p 2 + 2pq + q 2 p2 = individuals homozygous for first allele

2pq = individuals heterozygous for alleles q2 = individuals homozygous for second allele

60

60

Hardy-Weinberg Principle

p 2 + 2pq + q 2 and p+q = 1 (always two alleles)

16 cats white = 16bb then (q 2 = 0.16)

This we know we can see and count!!!!!

If p + q = 1 then we can calculate p from q 2

Q = square root of q 2 = q √.16 q=0.4

p + q = 1 then p = .6 (.6 +.4 = 1)

P 2 = .36

All we need now are those that are heterozygous (2pq)

(2 x .6 x .4)=0.48

.36 + .48 + .16

61

61

Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium

62

62

Five Agents of Evolutionary Change

Mutation

Mutation rates are generally so low they have little effect on

Hardy-Weinberg proportions of common alleles.

ultimate source of genetic variation

Gene flow movement of alleles from one population to another tend to homogenize allele frequencies

63

63

Five Agents of Evolutionary Change

Nonrandom mating assortative mating - phenotypically similar individuals mate

Causes frequencies of particular genotypes to differ from those predicted by Hardy-Weinberg.

64

64

Five Agents of Evolutionary Change

Genetic drift – statistical accidents.

Frequencies of particular alleles may change by chance alone.

important in small populations founder effect - few individuals found new population (small allelic pool) bottleneck effect - drastic reduction in population, and gene pool size

65

65

Genetic Drift - Bottleneck Effect

66

66

Five Agents of Evolutionary Change

Selection – Only agent that produces adaptive evolutionary change artificial - breeders exert selection natural - nature exerts selection variation must exist among individuals variation must result in differences in numbers of viable offspring produced variation must be genetically inherited natural selection is a process, and evolution is an outcome

67

67

Five Agents of Evolutionary Change

Selection pressures: avoiding predators matching climatic condition pesticide resistance

68

68

Measuring Fitness

Fitness is defined by evolutionary biologists as the number of surviving offspring left in the next generation.

relative measure

Selection favors phenotypes with the greatest fitness.

69

69

Interactions Among Evolutionary Forces

Levels of variation retained in a population may be determined by the relative strength of different evolutionary processes.

Gene flow versus natural selection

Gene flow can be either a constructive or a constraining force.

Allelic frequencies reflect a balance between gene flow and natural selection.

70

70

Natural Selection Can Maintain

Variation

Frequency-dependent selection

Phenotype fitness depends on its frequency within the population.

Negative frequency-dependent selection favors rare phenotypes.

Positive frequency-dependent selection eliminates variation.

Oscillating selection

Selection favors different phenotypes at different times.

71

71

Heterozygote Advantage

Heterozygote advantage will favor heterozygotes, and maintain both alleles instead of removing less successful alleles from a population.

Sickle cell anemia

Homozygotes exhibit severe anemia, have abnormal blood cells, and usually die before reproductive age.

Heterozygotes are less susceptible to malaria.

72

72

Sickle Cell and Malaria

73

73

Forms of Selection

Disruptive selection

Selection eliminates intermediate types.

Directional selection

Selection eliminates one extreme from a phenotypic array.

Stabilizing selection

Selection acts to eliminate both extremes from an array of phenotypes.

74

74

Kinds of Selection

75

75

Selection on Color in Guppies

Guppies are found in small northeastern streams in

South America and in nearby mountainous streams in

Trinidad.

Due to dispersal barriers, guppies can be found in pools below waterfalls with high predation risk, or pools above waterfalls with low predation risk.

76

76

Evolution of Coloration in Guppies

77

77

Selection on Color in Guppies

High predation environment - Males exhibit drab coloration and tend to be relatively small and reproduce at a younger age.

Low predation environment - Males display bright coloration, a larger number of spots, and tend to be more successful at defending territories.

In the absence of predators, larger, more colorful fish may produce more offspring.

78

78

Evolutionary Change in Spot Number

79

79

Limits to Selection

Genes have multiple effects pleiotropy

Evolution requires genetic variation

Intense selection may remove variation from a population at a rate greater than mutation can replenish.

thoroughbred horses

Gene interactions affect allelic fitness epistatic interactions

80

80

81

81

Population genetics

• genetic structure of a population

• alleles

• genotypes group of individuals of the same species that can interbreed

Patterns of genetic variation in populations

Changes in genetic structure through time

82

82

Describing genetic structure

• genotype frequencies

• allele frequencies

rr = white

Rr = pink

RR = red

83

83

Describing genetic structure

• genotype frequencies

• allele frequencies

200 white

500 pink genotype frequencies:

200/1000 = 0.2 rr

300 red

500/1000 = 0.5 Rr

300/1000 = 0.3 RR total = 1000 flowers

84

84

Describing genetic structure

• genotype frequencies

• allele frequencies

200 rr = 400 r

500 Rr = 500 r

= 500 R

300 RR = 600 R allele frequencies:

900/2000 = 0.45 r

1100/2000 = 0.55 R total = 2000 alleles

85

85

for a population with genotypes:

100 GG

160 Gg

140 gg

calculate:

Genotype frequencies

Phenotype frequencies

Allele frequencies

86

86

for a population with genotypes:

100 GG

160 Gg

140 gg

calculate:

Genotype frequencies

260

100/400 = 0.25 GG

160/400 = 0.40 Gg

140/400 = 0.35 gg

0.65

Phenotype frequencies

260/400 = 0.65 green

140/400 = 0.35 brown

Allele frequencies

360/800 = 0.45 G

440/800 = 0.55 g

87

87

another way to calculate allele frequencies:

100 GG

160 Gg

Genotype frequencies

0.25 GG

0.40 Gg

0.35 gg g g

G

G

0.25

0.40/2 = 0.20

0.40/2 = 0.20

0.35

140 gg

Allele frequencies

360/800 = 0.45 G

440/800 = 0.55 g

OR [0.25 + (0.40)/2] = 0.45

[0.35 + (0.40)/2] = 0.65

88

88

Population genetics – Outline

What is population genetics?

Calculate

- genotype frequencies

- allele frequencies

Why is genetic variation important?

How does genetic structure change?

89

89

Genetic variation in space and time

Frequency of Mdh-1 alleles in snail colonies in two city blocks

90

90

Genetic variation in space and time

Changes in frequency of allele F at the Lap locus in prairie vole populations over 20 generations

91

91

Genetic variation in space and time

Why is genetic variation important?

potential for change in genetic structure

• adaptation to environmental change

- conservation

•divergence of populations

- biodiversity

92

92

Why is genetic variation important?

variation no variation global warming survival

EXTINCTION!!

93

93

Why is genetic variation important?

variation no variation

94

94

Why is genetic variation important?

divergence variation no variation

NO DIVERGENCE!!

95

95

Natural selection

Resistance to antibacterial soap

Generation 1: 1.00 not resistant

0.00 resistant

96

96

Natural selection

Resistance to antibacterial soap

Generation 1: 1.00 not resistant

0.00 resistant

97

97

Natural selection

Resistance to antibacterial soap

Generation 1: 1.00 not resistant

0.00 resistant

Generation 2: 0.96 not resistant

0.04 resistant mutation!

98

98

Natural selection

Resistance to antibacterial soap

Generation 1: 1.00 not resistant

0.00 resistant

Generation 2: 0.96 not resistant

0.04 resistant

Generation 3: 0.76 not resistant

0.24 resistant

99

99

Natural selection

Resistance to antibacterial soap

Generation 1: 1.00 not resistant

0.00 resistant

Generation 2: 0.96 not resistant

0.04 resistant

Generation 3: 0.76 not resistant

0.24 resistant

Generation 4: 0.12 not resistant

0.88 resistant

100

100

Natural selection can cause populations to diverge divergence

101

101

Selection on sickle-cell allele aa – abnormal ß hemoglobin sickle-cell anemia very low fitness

AA – normal ß hemoglobin vulnerable to malaria intermed.

fitness

Aa – both ß hemoglobins resistant to malaria high fitness

Selection favors heterozygotes ( Aa ).

Both alleles maintained in population ( a at low level).

102

102

How does genetic structure change?

• mutation

• migration

• genetic drift genetic change by chance alone

• natural selection

• sampling error

• misrepresentation

• small populations

• non-random mating

103

103

Genetic drift

Before:

8 RR

8 rr

0.50 R

0.50 r

After:

2 RR

6 rr

0.25 R

0.75 r

104

104

How does genetic structure change?

• mutation

• migration

• natural selection

• genetic drift

• non-random mating cause changes in allele frequencies

105

105

How does genetic structure change?

• mutation

• migration

• natural selection

• genetic drift

mating combines alleles into genotypes

• non-random mating

• non-random mating

non-random allele combinations

106

106

A

A A

A a

A

A

A

0.8

A

0.8

a

0.2

AA

0.8 x 0.8

Aa

0.8 x 0.2

aa

AA allele frequencies:

A = 0.8

A = 0.2

a

0.2

aA

0.2 x 0.8

aa

0.2 x 0.2

genotype frequencies:

AA = 0.8 x 0.8 = 0.64

Aa = 2(0.8 x0.2) = 0.32

aa = 0.2 x 0.2 = 0.04

107

107

Example: Coat color

B__ = black bb = red

Herd of 200 cows:

100 BB, 50 Bb and 50 bb

108

108

Allele frequency

No. B alleles = 2(100) + 1(50) = 250

No. b alleles = 2(50) + 1(50) = 150

Total No. = 400

Allele frequencies: f(B) = 250/400 = .625 f(b) = 150/400 = .375

109

109

genotypic frequencies f(BB) = 100/200 = .5 f(Bb) = 50/200 = .25 f(bb) = 50/200 = .25 phenotypic frequencies f(black) = 150/200 = .75

f(red) = 50/200 = .25

110

110

Previous example: counted alleles to compute frequencies. Can also compute allele frequency from genotypic frequency. f(A) = f(AA) + 1/2 f(Aa) f(a) = f(aa) + 1/2 f(Aa)

111

111

Previous example, we had f(BB) = .50, f(Bb) = .25, f(bb) = .25. allele frequencies can be computed as: f(B) = f(BB) + 1/2 f(Bb)

= .50 + 1/2 (.25) = .625

f(b) = f(bb) + 1/2 f(Bb)

= .25 + 1/2 (.25) = .375

112

112

Mink color example:

B_ = brown bb = platinum (blue-gray)

Group of females (.5 BB, .4 Bb, .1 bb) bred to heterozygous males (0 BB, 1.0 Bb, 0 bb).

113

113

Allele frequencies among the females?

f(B) = .5 + 1/2(.4) = .7

f(b) = .1 + 1/2(.4) = .3

Allele frequencies among the males?

f(B) = 0 + 1/2(1) = .5

f(b) = 0 + 1/2(1) = .5

114

114

Expected genotypic, phenotypic and allele frequencies in the offspring?

sires

.5 B .5 b

________________ dams .7 B .35 BB .35 Bb

.3 b .15 Bb .15 bb

115

115

Expected frequencies in offspring

Genotypic

.35 BB

.50 Bb

.15 bb

Phenotypic

.85 brown

.15 platinum

116

116

Allele frequencies in offspring

f(B) = f(BB) + .5 f(Bb)

= .35 + .5(.50) = .6

f(b) = f(bb) + .5 f(Bb)

= .15 + .5(.50) = .4

117

117

Also note: allele freq. of offspring = average of sire and dam f(B) = 1/2 (.5 + .7) = .6

f(b) = 1/2 (.5 + .3) = .4

118

118

Hardy-Weinberg Theorem

Population gene and genotypic frequencies don’t change over generations if is at or near equilibrium.

Population in equilibrium means that the populations isn’t under evolutionary forces

(Assumptions for Equilibrium*)

119

119

Assumptions for equilibrium

large population (no random drift)

Random mating no selection no migration (closed population) no mutation

120

120

Hardy-Weinberg Theorem

Under these assumptions populations remains stable over generations.

It means: If frequency of allele A in a population is =.5, the sires and cows will generate gametes with frequency =.5 and the frequency of allele

A on next generation will be =.5!!!!!

121

121

Hardy-Weinberg Theorem

Therefore:

It can be used to estimate frequencies when the genotypic frequencies are unknown.

Predict frequencies on the next generation.

122

122

Hardy-Weinberg Theorem

If predicted frequencies differ from observed frequencies Population is not under Hardy-

Weinberg Equilibrium.

Therefore the population is under selection, migration, mutation or genetic drift.

Or a particular locus is been affected by the forces mentioned above.

123

123

Hardy-Weinberg Theorem

(2 alleles at 1 locus)

Allele freq.

f(A) = p f(a) = q p + q = 1

Sum of all alleles = 100%

Genotypic freq.

f(AA) = p 2 Dominant homozygous f(Aa) = 2 pq Heterozgous f(aa) = q 2 Recessive homozygous p 2 + 2 pq + q 2 = 1

Sum of all genotypes = 100%

124

124

Hardy-Weinberg Theorem

Allele freq.

f(A) = p f(a) = q p + q = 1

Sum of all alleles = 100%

Genotypic freq.

f(AA) = p 2 Dominant homozygous f(Aa) = 2 pq Heterozgous f(aa) = q 2 Recessive homozygous p 2 + 2 pq + q 2 = 1

Sum of all genotypes = 100%

Gametes A (p) a(q)

A(p) a(q)

AA

(pp) aA

(qp)

Aa

(pq) aa

(qq)

AA = p*p = p 2

Aa = pq + qp = 2pq

Aa = q*q = q 2

125

125

Example use of H-W theorem

1000-head sheep flock. No selection for color. Closed to outside breeding.

910 white (B_)

90 black (bb)

126

126

Start with known: f(black) = f(bb) = .09 =q 2 q

q

2

.

09

Then, p = 1 – q = .7 = f(B)

.

3

f ( b ) f(BB) = p 2 = .49

f(Bb) = 2pq = .42

f(bb) = q 2 = .09

127

127

In summary:

Allele freq.

f(B) = p = .7 (est.) f(b) = q = .3 (est.)

Phenotypic freq.

f(white) = .91 (actual) f(black) = .09 (actual)

Genotypic freq.

f(BB) = p 2 = .49 (est.) f(Bb) = 2pq = .42 (est.) f(bb) = q 2 = .09 (actual)

128

128

Mink example using H-W

Group of 2000 (1920 brown, 80 platinum) in equilibrium. We know f(bb) = 80/2000 = .04 = q 2 f(b) = (q 2 ) = .04 = .2

f(B) = p = 1- q = .8 f(BB) = p 2 = .64

f(Bb) = 2pq = .32

129

129

Forces that affect allele freq.

1. Mutation

2. Migration

3. Selection

4. Random (genetic) drift

Selection and migration most important for livestock breeders.

130

130

Mutation

Change in base DNA sequence.

Source of new alleles.

Important over long time-frame.

Usually undesirable.

131

131

Migration

Introduction of allele(s) into a population from an outside source.

Classic example: introduction of animals into an isolated population.

others: new herd sire.

opening herd books.

“under-the-counter” addition to a breed.

132

132

Change in allele freq. due to migration

p mig

= m(P m

-P o

) where

P m

P o

= allele freq. in migrants

= allele freq. in original population m = proportion of migrants in mixed pop.

133

133

Migration example

100 Red Angus (all bb, p

0 purchase 100 Bb (p m

p = m(p m

- p o

= .5)

= 0)

) = .5(.5 - 0) = .25

new p = p

0 new q = q

0

+ p = 0 + .25 = .25 = f(B)

+ q = 1 - .25 = .75 = f(b)

134

134

Random (genetic) drift

Changes in allele frequency due to random segregation.

Aa .5 A, .5 a gametes

Important only in very small pop.

135

135

Selection

Some individuals leave more offspring than others.

Primary tool to improve genetics of livestock.

Does not create new alleles. Does alter freq.

Primary effect change allele frequency of desirable alleles.

136

136

Example: horned/polled cattle

100-head herd (70 HH, 20 Hh, and 10 hh).

Genotypic freq.: f(HH) = .7, f(Hh) = .2, f(hh) = .1

Allele freq.: f(H) = .8, f(h) = .2

Suppose we cull all horned cows. Calculate allele and genotypic frequencies after culling?

137

137

After culling

f(HH) = .7/.9 = .778

f(Hh) = .2/.9 = .222

f(hh) = 0 f(H) = .778 + .5(.222) = .889

f(h) = 0 + .5(.222) = .111

p = .889 - .8 = .089

138

138

2nd example

Cow herd with 20 HH, 20 Hh, and 60 hh

Initial genotypic freq.: .2HH, .2Hh, .6hh

Initial allele frequencies: f(H) = .2 + 1/2(.2) = .3

f(h) = .6 + 1/2(.2) = .7

Again, cull all horned cows.

139

139

Genotypic freq (HH) = .2/.4 = .5

freq (Hh) = .2/.4 = .5

freq (hh) = 0

p = .75 - .3 = .45

Allele freq.

f(H) = .5 + 1/2(.5) = .75

f(h) = 0 + 1/2(.5) = .25

Note: more change can be made when the initial frequency of desirable gene is low.

140

140

3rd example

initial genotypic freq. .2 HH, .2 Hh, .6 hh.

Initial allele freq. f(H) = .3 and f(h) = .7

Cull half of the horned cows.

141

141

Genotypic f

(HH) = .2/.7 = .2857

f (Hh) = .2/.7 = .2857

f (hh) = .3/.7 = .4286

p = .429 - .3 = .129

Allele freq.

f(H) = .2857 + 1/2(.2857) = .429

f(h) = .4286 + 1/2(.2857) = .571

Note: the higher proportion that can be culled, the more you can change allele freq.

142

142

Selection Against Recessive Allele

.5

.7

.9

Allele Freq.

A a

.1

.3

.9

.7

.5

.3

.1

Genotypic Freq.

AA Aa

.01

.09

.18

.42

.25

.49

.81

.50

.42

.18

aa

.81

.49

.25

.09

.01

143

143

Factors affecting response to selection

1. Selection intensity

2. Degree of dominance

(dominance slows progress)

Initial allele frequency (for a one locus)

Genetic Variability (Bell Curve)

144

144