Philosophy 220

advertisement

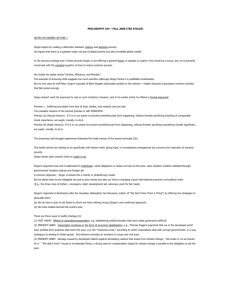

Poverty and World Hunger: Singer, and Arthur Singer, "Famine, Affluence and Morality" Singer uses a consequentialist standpoint to evaluate our moral responsibilities in the face of widespread poverty, starvation and need. He offers two versions of a principle aimed to specify this responsibility: Strong Principle: "If it is in our power to prevent something bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance, we ought, morally, to do it" (454). ○ What does Singer mean by "without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance"? Answer "...without causing anything else comparably bad to happen, or doing something that is wrong in itself, or failing to promote some moral good, comparable in significance to the bad thing that we can prevent.” Weak Principle: "If it is in our power to prevent something very bad from happening, without sacrificing anything morally significant, we ought, morally, to do it" (Ibid.). The Argument 1. 2. 3. 4. Suffering and death from lack of food, shelter, and medical care are bad. The Strong Principle. (You could use the weak one as well.) It is within our power to prevent suffering and death from lack of food, shelter and medical care, without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance. So, we ought, morally, work to prevent such suffering and death. Implication As Singer makes clear, there is a surprising and significant implication of this argument. Suppose my family income is $200,000 per year and, moved by the plight of the world's poor, I give ten dollars to a global disaster relief agency such as Oxfam or Doctors without Borders. Then I think about going to the movies. But wait, I could instead donate another ten dollars to Oxfam. And another, and another. Singer's argument seems to conclude that I should continue giving this way until further giving would lead to a comparable moral sacrifice, maybe all the way to the global poverty level. Can This be Right? This seems implausible, but Singer uses an analogical application of the Strong Principle to buttress his case. Suppose I am walking by a pond in the woods. I'm alone. I see a small child drowning in shallow water. I could save the child easily and without risk to myself, suffering only the slight inconvenience of getting my pants muddy. Singer says one is morally obligated to pull the drowning child from the shallow pond to prevent the drowning. Singer insists that there is no morally significant difference between the drowning child case and the decision I face when I could spend money on myself or instead donate resources to famine relief. So, if you think you should save the child, you should get out your checkbook. Duty? Another implication of this argument is that the traditional, conventional way of drawing the line between moral duty and charity cannot be maintained. According to common moral opinion, one is morally bound not to harm others, but helping others is morally optional. If you do help others, you are going above and beyond the call of duty, and are to be commended for being charitable—doing good you were not duty-bound to do. On Singer's Strong Principle, this way of characterizing the relationship between duty and charity is turned upside down. Singer would agree with Kant that we do have a duty to be charitable, but he would go further and insist that the duty is a defined one. Objections and Replies Pt. 1 Objection 1. The child in the example is close by and the global poor one might aid are far away . Also, the child will drown right now if you do not help, but giving to relief agencies will only prevent deaths in the future. Singer's reply: Mere distance in time and distance in space are in and of themselves irrelevant to the determination of what one ought to do. Objection 2. In the drowning child example, you are the only one who could help. In the case of disaster relief, you are one of many people who could help. Singer's reply: It does not matter morally how many people could help the situation. Suppose 100 people are on the beach, and see a child drowning in shallow water. Any of the 100 could help. If no one helps, all do wrong. That others could have helped does not lessen your responsibility. Objections and Replies Pt. 2 Objection 3. The argument's conclusion is drastically at odds with our current moral beliefs so cannot be right. Singer's reply: Why assume our current moral beliefs are all correct? Singer has asserted a principle, and tried to show what conduct is required by the principle. If the principle is acceptable, and the reasoning from the principle is sound, the conclusion, even if at odds with current opinions, stands. Objection 4. The morality that Singer is proposing is far beyond the capacities of the ordinary person, so should not be accepted and established in society. Singer's reply: "The issue here is: Where should we draw the line between conduct that is required and conduct that is good although not required, so as to get the best possible result?" This looks to be a hard empirical issue, and it is far from obvious that the answer is that moral requirements should be minimal. Arthur, "Hunger and Obligation" Arthur criticizes Singer's conclusions in "Famine, Affluence and Morality." His criticism rests on his analysis of Singer's Strong Principle. On his reading, the Strong Principle is justified by Singer explicitly with reference to the drowning child analogy, but implicitly by reference to what Arthur identifies as a principle of Moral Equality: the poor are just as important as we are, so it would be unjust if I prefer my trivial interests to preservation of their lives. Moral Equality? At first glance, this principle seems noncontroversial (perhaps this is why Singer never really highlights it), but Arthur argues that there is more to the question than meets the eye. What the equality principle overlooks is another important moral concept: entitlement. Moral Entitlement According to Arthur, and in agreement with much philosophical and legal precedent, there are two kinds of entitlements: rights and desert. Entitlements of Rights: we are not obligated to heroism (e.g., to give up, our kidneys or eyes or grant sexual favors to save someone else's life or sanity (459)). Strangers have only negative rights (rights of noninterference), unless we have volunteered for it. Entitlements of Desert: we have a right to what we deserve based on the past. Story of the industrious and lazy farmers (460). Implications Our moral system already gives weight to both future and past, consequences and entitlements. Of course we ought to help the drowning child if nothing of greater importance is at stake; but our moral code must take into account both consequences and entitlements. According to Arthur, Singer just completely ignores backward-looking considerations. We do have obligations to help others, but they don't overwhelm our moral entitlements (e.g., to go to the movies). This is a kind of moderate position.