Shakespeare titled the play within the play that takes place in Act 3

advertisement

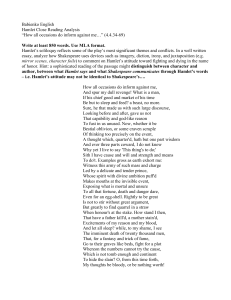

Shakespeare titled the play within the play that takes place in Act 3, Scene 2 of Hamlet “The Mousetrap.” By producing a play for his uncle Claudius, Hamlet hopes to “catch the conscience of the king”—to confirm his own suspicions that Claudius did, in fact, poison Hamlet senior and to let Claudius know that Hamlet is aware of his uncle’s fratricide (50). Hamlet narrates the play as the players act out the story of a murder in Vienna. As the players act out the murder of a Viennese king, Gonzago, Claudius stops the play and rushes out of the room, which Hamlet sees as indicative of his uncle’s guilt. While contemplating producing the play, Hamlet says, “I’ll have these players/ Play something like the murder of my father/ Before mine uncle. I’ll observe his looks,/ I’ll tent him to the quick. If he but belch,/ I’ll know my course” (50). Here Hamlet clearly lays out the relationship between this play within a play and revenge. The revenge is directly initiated by Claudius’ reaction to Hamlet’s “Mousetrap.” And, as Freud would suggest, it is through the play that Hamlet begins to come to terms with the murder of his father. The style with which this play within the play is written marks a dramatic departure from Shakespeare’s throughout the rest of Hamlet. The language here is often characterized as crude and bombastic. Yet critic Carol Replogle asserts that this is an example of the “deliberate adoption of a style whose ‘badness’ meets the dramatic needs of the task at hand” in the sense that the “ornate texture and archaic flavor were particularly appropriate for setting apart a play within a play from the main action” (Replogle 150, 158). She points out that at the time Shakespeare wrote Hamlet, the play within a play had become a very common aspect of Elizabethan drama. It was conventional for these “inset devices” to be much more heavily stylized, as is the case here—the play within the play appears in rhymed iambic pentameter couplets. She also argues that many of the rhymes that have been criticized for being awkward here (flies and enemies, moon and done) would have rhymed perfectly to Shakespeare’s contemporaries (Koekeritz 434, 464). Further, the various inversions used by Shakespeare here such as cacosynthetons and anastrophes that do much to make the wording sound cumbersome and unskillful would not have been as foreign to the Elizabethan ear (Replogle 155).1 The “traditional formulaic dramatic style” and presence of archaic words both contribute to the buildup of dramatic tension and serve, by not being distracting, to focus attention on the coming crisis of Hamlet’s revenge (159). The anticipation that Shakespeare seeks to create in this scene is furthered by his use of monosyllables and end-stopped lines. As Repogle points out, these devices give the play a very slow movement (159). Critic John Doebler suggests that the word “mousetrap,” the title which Hamlet assigns to the play, would carry “rich iconographical associations” for the Medeival and Renaissance audiences that Shakespeare wrote for that a contemporary reader would likely miss (Doebler, 162). Given the commonplace nature of this symbol in the Renaissance, Doebler asserts that the “brief mention of the play’s title itself” can be seen as “a symbolic microcosm communicating to the audience much of the elaborate irony on which the whole dramatic action of Hamlet pivots” (162). Doebler cites the myriad of connotations associated with mice including gluttony, corruption of all they touch, charges of uncleanliness in the Bible, and the Augustinian 1 Replogle writes that “anastrophe," is “a simple inversion of syntactic order… The normal subject-verb-object word order might be changed to object-subject-verb, subject-object-verb, or verb-object-subject as in "Discomfort you, my lord, it nothing must" (3. 2. 176). Related to anastrophe is "cacosyntheton," which was considered a more radical inversion. The placing of an adjective after the noun it modified would be considered in this category, and there are several of these in the piece: "Which now, like fruit unripe sticks on the tree" (line 200) and "Thoughts black, hands apt, drugs fit, and time agreeing" (line 266).” conception of the cross as a mousetrap on which the devil was ensnared and subsequently caused his downfall. The Augustinian conception of the mousetrap, which would have been very familiar to Shakespeare’s contemporary Englishmen, dovetails perfectly with the outcome of Hamlet’s plan for revenge as “when the trap is set the devil snaps at the bait; the mouse is caught; but he is caught by one who must himself die to defeat him fully.” Hamlet’s death parallels Jesus’ and “results in tragic resurrection, in the sense that he has died while saving the kingdom for mankind” (169). Thus, by conflating Claudius with a mouse and the play with the initial trap in Hamlet’s plan of revenge, Shakespeare uses the play as a critical device in the conveying the overarching meaning of the entire play to the audience.