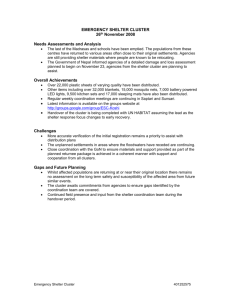

final - Shelter Cluster

advertisement