Travel literature - Dipartimento di Lingue e Letterature Straniere e

advertisement

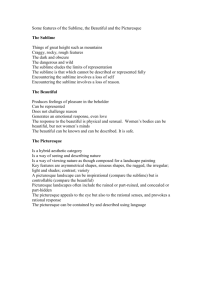

Travel literature • Travel books – Popular reading from 16th cent. on – Personal impressions, anecdotes, autobiographical details. – Some information • Guidebooks – More anonymous •Both contribute to the construction of the image of a country. •Shape the collective imagination Travel to Italy Middle Ages • Pilgrimage, university attendance • 16th-17th centuries – young aristocrats often travelled through Europe with a tutor – Visited courts of princes, universities, libraries – in search of polish, civilised manners, learning and pleasure • 18th century, Grand Tour – widespread social practice – middle classes and women. • 19th century: – Whole families – From midcentury mass tourism, thanks to transportation and the birth of tourist offices (Thomas Cook) PELLEGRINI DEL MEDIOEVO Italy prime destination of 18th century Grand Tour • 18th century devotion to classicism • 18th century devotion to Art • 18th century cult of Nature • Italy a common homeground for Europe. The Grand Tour: search for a common identity 18th century devotion to classicism Study, imitation and translation of the classics Buildings imitating classical models are raised in England Desire of first hand knowledge of remains of classical architecture • Importance of Rome as destination German aesthetics at the basis of the reinterpretation of Italy as a locus classicus Lessing’s Laocoon Winckelmann’s thoughts on the imitations of the Greeks. His admiration for the Belvedere Apollo 18th century devotion to Art • Familiarity with great Renaissance Italian art – From collections of former grand tourists – From imitations • Desire for firsthand knowledge – Visit to art galleries – Visit to artists’ studios • Purchase and commissioning of original and imitation work • Commissioning portraits of visitors with classical or Italian background • Desire to fit the fragments stored in one’s imagination into the whole picture 18th century cult of Nature • Admiration of Italian landscape new aspect of last third of the century . – 16th and 17th centuries looked at nature from agricultural and scientific point of view. • • • • Aesthetic category of the picturesque Aesthetic category of the sublime Influence of Rousseau Influence of landscape painting – Salvator Rosa, Claude Lorrain, Jacob Philipp Hackert etc. The sublime • Aesthetic category of the sublime, first (supposedly) introduced by Longinus, Greek rhethorician, author of the treatise On the Sublime. • Boileau • Theorized in England by Edmund Burke in A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1765) • Beauty cannot be explained by reason (as Winckelmann and neo.classical aesthetics did) – Aesthetic thrill caused by natural elements that inspire awe or fear and remind man of the mightiness of divine creation and threat of destruction • High mountains, cliffs, volcanoes, waterfalls, caves • Thunderstorms, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions • Threatening remains of the past, reminding man of possibility Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain and danger, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime; it is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling. (Burke) The picturesque • First discussed by landscape gardener William Gilpin • Nature seen as a pictorial arrangement of landscape and human elements, a framed landscape • Scenes of daily life – Made livelier by persons and animals • Scenes containing ruins and examples of old architecture were considered particularly picturesque. • What is beautiful in its natural state with a certain "roughness” “irregularity” and ”variety” but with Italy and the picturesque • Italy is the imaginary homeland and textual model of picturesque theory • Gilpin advocated picturesque travel, in search of amusement through the enjoyment of picturesque scenery [Picturesque beauty]. we pursue through the scenery of nature. We seek it among all the ingredients of landscape -- trees -- rocks -- broken-grounds -- woods -- rivers -- lakes -- plains -- vallies -mountains -- and distances..[…] Besides the inanimate face of nature, it's living forms fall under the picturesque eye, in the course of travel; and are often objects of great attention. […] In the same manner animals are the objects of our attention, whether we find them in the park, the forest, or the field. […] But among all the objects of art, the picturesque eye is perhaps most inquisitive after the elegant relics of ancient architecture; the ruined tower, the Gothic arch, the remains of castles, and abbeys. These are the richest legacies of art. They are consecrated by time; and almost deserve the veneration we pay to the works of nature itself. (fromWilliam Gilpin, Three Essays on Picturesque Beauty,. Essay II. On Picturesque Travel (1794). Europe’s museum and Europe’s mausoleum • Contemporary Italy seen as incomplete, deficient or decadent in comparison to its glorious classical past • Neglect of ruins= neglect of common European legacy • Misuse of archeological remains for new constructions • No present history • The past overshadows the present; ruins, monuments and paintings overshadow real people Immoral Italy • Italian sexuality and gender roles exert a “disturbing fascination” on English visitors – sensuousness and liberty • Italians seen as soft, effeminate – creativity a result of effeminacy • Cicisbeismo • Italy a sexual hot spot where young English gentlemen lose their innocence • Country peopled by go-betweens of both sexes, organizing a parallel initiation tour. • Italy a threat for the visitor Italian indigence and crime • A backward people • Live in primitive conditions – Lack of comfort and hygiene – Dirty, neglected urban environment • Poverty – Disease – Beggars • Dishonesty, cheating • Crime – theft – Pickpockets – Banditti (often romanticized) Catholicism • No longer an object of revulsion but rather of curiosity or ridicule • Superstitions, miracles, relics made fun of • Church ceremonies: folkloristic and exotic shows – Holy week in Rome “L’Italia senza gl’italiani” • Double rhetoric – Rapture over antiquity, art, nature and climate – Indifference to social and political set-up – Contempt for Italians • No longer machiavellian devils but “poor devils”. • Same descriptions as for third world countries • Grand tour a peaceful colonization, a cultural appropriation Eighteenth century travelogues • A written testimonial of one’s adventures on the Grand Tour • Structured personal narratives. • Often in diary or letter form • Close to autobiography Travelogues vs guidebooks • Guidebooks came into being at the start of mass tourism – Baedeker 1836 – John Murray’s 1837 • Travelogues strongly coloured by the personality of the writer / Guidebooks impersonal • Both give advice and information to the traveller • Distinction between the two genres blurred A symbolic Colonization • Colonization may also be a cultural discourse imposing the colonizer’s views onto places and people. – Edward Said Orientalism • English government involved in commercialization of antiquities. – Excavations in Rome – Excavations in Pompei (Lord Hamilton) • Travellers brought back souvenirs: pieces of ruins, artwork; they commissioned paintings of themselves • Turned Italy into a sort of theme park The end of the great season of the Tour • The Napoleonic empire brought actual colonisation • British excluded from travelling in Italy until 1815 • The Romantic myth of Italy tinged by political connotations • By mid nineteenth century mass transportation. Railwats. • Thomas Cook • Official guidebooks Murray’s Baedecker’s • Victorian England sees the beginnings of mass tourism – Climatic stays – The” season” The Package Tour – Combined transportation, lodgings, sightseeing, money exchange, etc. – First organized by Thomas Cook (1841) – Cook organized package tours to allow people to attend temperance meetings (of the Baptist church) – Cook negotiated a special fare due to the large number of people. – First Thomas Cook tours abroad 1855 for Paris Exhibition. – First Italian tour took place in the summer of 1864. Tivoli; Temple of the Sibyl and the Campagna 1765-70 Wilson Paesaggio italiano” Turner’s debt was explicit: many years before he made his own trip to the Roman Campagna, he copied the Kimbell painting, though omitting the large tree Distant View of Maecenas’ Villa, Tivoli about 1756-70 Tivoli. 1817 Turner's 'Tivoli' is sometimes cited as an early example of Turner treating light effects in his characteristic manner. Turner's approach greatly influenced French artists of his own generation--and the young Impressionists to follow. Tivoli and the Roman Campagna (after Wilson) – 1798 ( Tate-London) Turner copied the Kimbell painting, omitting the large tree and figures.