Figure 9-1: The Ontology of Cyberspace

advertisement

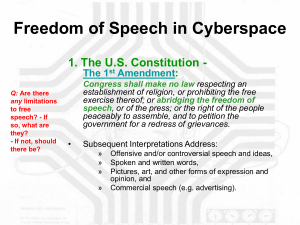

Regulating Cyberspace Should cyberspace be regulated? Can it be regulated? Which aspects of the 'Net should be regulated? Who should be responsible for carrying out the regulatory functions – the government, private organizations, or Internet users themselves? Cyberspace Regulation Two questions need to be answered: (1) What exactly do we mean by cyberspace? (2) What exactly is meant by regulation (and, in particular, "regulation" as it applies to cyberspace)? The Ontology of Cyberspace Cyberspace, which for our purposes can be equated with the Internet, can be defined as the network of interconnected computers. What exactly is cyberspace? Is it a "place" – i.e., a virtual space that consists of all the data and information that resides in the connected servers and databases that make up the Internet? Or is cyberspace a "medium" of some sort? Cyberspace as a Medium Mike Goodwin (1995) believes that the Internet is a new kind of medium. It is a medium that is significantly different from earlier media, such as the telephone or television. The telephone as a "one-to-one medium," and television as a "one-to-many medium.“ Goodman suggests that the Internet be characterized as a "many-to-many medium" in which one does not need to be wealthy to have access and in which one does not need to win the approval of an editor or a publisher to speak his or her mind. Cyberspace as a public space Camp and Chien (2000) note that there are four types of media: publisher, broadcast, distributor, and common carrier. An example of a publisher would be a newspaper or a magazine; and examples of broadcast media include television and radio. Telephone companies and cable companies can be considered instances of common carriers. Camp and Chien argue that none of the four media models are appropriate for understanding the 'Net. Instead, they believe that a spatial model – one in which cyberspace is viewed a "public space with certain digital characteristics" – is a more plausible way to conceive of the Internet. Camp and Chien also believe that operating from such a model can influence our decisions about public policies on the Internet. Figure 9-1: The Ontology of Cyberspace Cyberspace Public Space (or Place) (bookstore model) Broadcast Medium (common carrier model) Two Different Senses of "Internet Regulation“ To "regulate" typically means to monitor or control a certain product, process, or set of behaviors according to certain requirements, standards, or protocols. At least two different senses of “regulation” have been used to debate the question of cyberspace regulation. Sometimes the focus is on regulating the content of cyberspace, as in the case of whether on-line pornography and hate speech should be censored on the 'Net. And sometimes it focuses on processes – i.e., rules and policies – should be implemented and enforced in commercial transactions in cyberspace. In physical space, both kinds of regulation also occur. Regulatory Agencies in Physical Space Content-based examples: FDA; Local and State Boards of Health; Liquor Control Board. Process-based examples: FTC; FCC’ SEC. Figure 9-2: Two Modes of Cyberspace Regulation Cyberspace Regulating Content Speech Regulating Process Commerce Four Modes of Regulating Cyberspace: The Lessig Model Lessig (1999) describes four distinct but interdependent constraints, which he calls "modalities," for regulating behavior: Laws; social norms; market pressures; Architecture. Analogy: Regulating Smoking Behavior in Physical Space Using the Lessig Model, we can: 1. Pass Laws Against Smoking; 2. Apply Social Pressure (Norms); 3. Apply Market Pressure (e.g., in Pricing Practices); 4. Use Architecture (e.g., no cigarettes in vending machines). Regulation by Code In cyberspace, Lessig notes that code is law. Lessig compares the architectures of NET 95 (Chicago) to NET 98 (Harvard). Net 95 favors Anonymity. Net 98 favors control. Elkin-Koren (2000) worries that control is exacerbated because information is being privatized. Privatizing Information Policy Litman (1999) also argues that information policy in cyberspace is becoming increasingly privatized. In 1998, a series of events contributed a transformation of the Internet into what Litman describes as a "giant American shopping mall." That year Congress passed three copyright-related acts that favored commercial interests: the DMCA, SBCTEA, and the NET Act. Also, the federal government transferred the process of registering domain names from the National Science Foundation – an independent government regulatory body – to ICANN, a private group that has been favorable to commercial interests. The Recording Industry of America sought to ban the manufacture of portable MP3 players on grounds that such devices could be used to play pirated music. The recording industry also tried to pressure computer manufacturers to embed code in their future computer systems that will make it impossible to use personal computers to download MP3 files and to burn CDs. Internet Domain Names and “Cybersquatting” The National Science Foundation (NSF) formerly controlled the licensing of domain names. www.domainname.com/gov/org. ICANN (Internet Corporation of Assigned Names and Numbers) took over the process from NSF. ICANN has been more business friendly. Anti-Cybersquatting Act In 1999, the Anticyberquatting Consumer Protection Act was passed. This Act protected against “trademark infringements” and “dilutions” for trademark owners. Controversial case arose: Amazon Bookstore vs. Amazon.com. HTML Metatags Metatags are used in HTML Code for Web sites. keyword metatags vs. description metatags. Keyword metatags, such as <baseball> and <Barry Bonds> enable Web page designers to identify search terms that can be used by search engines. Descriptive metatags enable the designer of a Web page to describe the contents of his or her page. For example, the description of a Web site for Barry Bonds might read: "Barry Bonds...plays for the San Francisco Giants...broke major league baseball's home record in 2001..." The description typically appears as one or more sentence fragments, directly beneath the Web page's listing in an Internet search result. HTML Metatags (continued) Controversial cases involving the use of metatags. Hypothetical case in the text (involving Keith, a student at Technical University, USA). Actual case – Bihari v. Gross. Bahari is a company in New York City that provides interior design services; Gross, a former associate of Bihari, registered "bihari.com" and "bahiriinteriors.com" domain names; Gross was forced to relinquish the domain names; Gross then embedded the keyword metatag "Bihari Interiors" in the HTML code for his Web site and included derogatory remarks about Bihari on his Web site. Hyperlinking on the Web Controversial issues in Deep Linking. Important question: Is a Web site analogous to property? Scenario in textnook – Maria’s Gallery Actual Case – Ticket Master vs. Microsoft. The controversy surrounding hyperlinking is still not resolved in the courts – the Ticket Master case was settled out of court. Spam Spam is e-mail that is (1) unsolicited, (2) promotional, and (3) sent in bulk to multiple users. This three characteristics distinguish spam from other forms of e-mail. Because spam is unsolicited, it can also be viewed as a form of communication that is nonconsensual. Not every nonconsensual e-mail that one receives, however, should necessarily be considered an instance of spam. Spam (continued) Spam "shifts costs" from the advertiser to several other parties, including Internet Service Providers (ISPs) and the recipients of their service (Spinello 1999). The cost shifting even affects the individual users of the Internet who are indirectly inconvenienced by spam. Because others must bear the cost for its delivery, spam is not cost free. Spam consumes valuable computer resources because: When spam is sent through ISPs, the result in wasted network bandwidth for the service providers; Spam puts an increased strain on the utilization of system resources such as disk storage space. Is Spam Unethical? Spinello argues that spam is morally objectionable because: (a) It has harmful consequences; (b) It violates the individual autonomy of Internet users. Spam consumes and strains valuable computing resources and “degrades” the fragile ecology of the Internet. Spam (continued) Many argue that explicit laws need to be passed to control the threat of spam. The e-Bay v. Bidder’s Edge case, which is not really about spam per se, illustrates some of the arguments used against spam as a form of behavior that consumes valuable system resources. Free Speech vs. Censorship and Content Control in Cyberspace Should certain forms of speech on the Internet should be censored? Do all forms of speech deserve to be protected under the constitutional guarantee of free speech. According to the First Amendment of the US Constitution: Congress shall make no law...abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press... The right to free speech is a conditional right. Censorship Catudal (1999) believes that an important distinction can be drawn between two types of censorship: "censorship by suppression“; "censorship by deterrence." Both forms of censorship presuppose that some "authorized person or group of persons" has judged some text or "type of text" to be objectionable on moral, political or other grounds. Censorship (continued) Censorship by suppression affects the prohibition of the objectionable "text" or material from being published, displayed, or circulated. Banning certain kinds of books from being published or prohibiting certain kinds of movies to be made would be examples of censorship by suppression. In this scheme, pornography and other objectionable forms of speech would not be allowed to exist on the Internet. Censorship (continued) Censorship by deterrence is a less drastic means of censoring. It does not suppress or block out objectionable material or forbid it from being published. Rather, it depends on threats of arrest, prosecution, conviction, and punishment against those who make an objectionable "text" available and those who acquire it. Heavy fines and possible imprisonment can be used to deter the publication and acquisition of this objectionable content. Pornography in Cyberspace The concept of pornography is often debated in the legal sphere in terms of notions such as obscenity and indecent speech. In Miller v. California (1973), the court established a three-part guideline for determining whether material is obscene under the law, and thus not protected by the First Amendment. According to this criteria, something is obscene if it: 1. depicts sexual (or excretory) acts whose depiction is specifically prohibited by law. 2. depicts these acts in a patently offensive manner, appealing to prurient interest as judged by a reasonable person using community standards. 3. has no serious literary, artistic, social, political, or scientific value. Pornography (continued) The Miller case has been problematic in attempting to enforce pornography laws. The second criterion includes three controversial notions: 1"prurient interest“; 2 "reasonable person“; 3 "community standards." Censorship (Continued) The term prurient is usually defined as having to do with lust and with lewd behavior. Has been challenged as being vague and arbitrary. Also, many have challenged the question of who exactly would count as a "reasonable person.“ Until recently, one might have assumed that the notion of a "community standard" would be fairly straightforward But what exactly is a community in cyberspace? Where more than one community is involved in a dispute involving pornography, whose community standards should apply? Censorship/Pornography The Amateur Auction BBS made sexually explicit images available to its members. Because the BBS was an electronic forum, its contents were available not only to residents of California but to users in other states and countries who had Internet access. A person living in Memphis, Tennessee became a member of the BBS and then downloaded on his computer in Tennessee sexually explicit pictures. Although including sexually explicit images on a BBS may not have been illegal in California, viewing such images was illegal under Tennessee State law. Criminal charges were brought against the operators of the California-based BBS, who were prosecuted in Tennessee. Censorship/Pornography The California couple was found guilty under Tennessee law of distributing obscenity under the local community standards that applied in Memphis Tennessee. This case raised issues that had to do with what was meant by "community standards" on the Internet. Can a community in cyberspace be defined simply in terms of geography? Or in the age of the Internet, should "community" be defined in terms of some other criteria? For example, can a cyber-community be better understood as an "electronic gathering place" where individuals who share common interests come together? Internet Pornography Laws and Protecting Children Online Many people first became aware of the amount of pornographic material available on the Internet through a controversial news story, entitled CyberPorn, which appeared in Time magazine in the summer of 1995. Time reported that there were 900,000 sexually explicit pornographic materials (pictures, film clips, etc.). Many people, including most lawmakers, were outraged when they learned about the amount of pornographic material that was so easily accessible to Internet users, including minors. It was later pointed out that the Internet study on which the Time magazine story was based, which had been conducted by a researcher at Carnegie Mellon University, was seriously flawed. Internet Pornography Laws and Protecting Children Online The Carnegie Mellon study accurately reported the number of pornographic images and pornographic Web sites that were available. But it failed to put this information into proper perspective. For example, the study made no mention of the fact that the percentage of pornographic sites relative to other sites on the Web was very low. However, the report caught the eye of many influential politicians, who set out to draft legislation in response to what they saw as the growth of the "pornography industry" on the 'Net. The result was the passage into law of Communications Decency Act (CDA) in early 1996. Pornography Laws The CDA was considered controversial from the outset, especially the section of the Act referred to as the Exon Amendment that dealt exclusively with on-line pornography. The constitutionality of CDA was soon challenged by the ACLU, as well as by other organizations. In the summer of 1996, CDA was struck down by a court in Philadelphia on grounds that it was too broad and that it violated the US Constitution. A portion of the CDA, known as the Child Pornography Protection Act (CPPA) of 1996, was determined to be constitutional. So even though CDA itself was overturned, critics took some refuge in the fact that the provision for child pornography remained in tact. Child Pornography Laws CPPA significantly broadens the definition of child pornography to include entire categories of images that many would not judge to be "child pornographic." The CPPA's definition of child pornography includes categories of images that some would judge not to be pornographic at all. Child pornography, according to CPPA, is defined as: ...any depiction, including a photograph, film, video, picture, or computer or computer-generated image or picture, whether made or produced by electronic, mechanical, or other means, of sexually explicit conduct... Pornography (Continued) In June 1998, Congress passed The Child On-Line Pornography Act (COPA). Many of COPA's proponents believed that this Act would pass constitutional muster. In February 1999, the US Supreme Court ruled that COPA was unconstitutional. So the only remaining federal law specifically directed at on-line pornography, which had managed to withstand constitutional scrutiny, was the CPPA of 1996 (a section of the original CDA). According to the CPPA, it was a crime to "knowingly send, receive, distribute, reproduce, sell, or possess more than three child pornographic images." On April 16, 2002, the US Supreme Court, in a ruling of 6-3, struck down a controversial section of CPPA as unconstitutional. Table 9-1: Internet-specific Child Pornography Laws CDA (Communications Decency Act) Passed in January 1996 and declared unconstitutional in July 1996. The lower court's decision was upheld by the US Supreme Court in 1997. CPPA (Child Pornography Protection Act) Passed as part of the larger CDA, but was not initially struck down in 1997 with the CDA. It was declared unconstitutional in April 2002. COPA (Child On-line Pornography Act) Passed in June 1998 and was declared unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court in February 1999. Two types of Controversial Speech in Cyberspace In addition to pornography, two additional kinds of speech that have been controversial in cyberspace are: hate speech; forms of speech that can cause physical harm to individuals and communities. Hate speech on the Internet often targets members of certain racial and ethnic groups. For example, white supremacist organizations such as the Klu Klux Klan (KKK) can include on their Web pages offensive remarks about African Americans and Jews. Because of the Internet, international "hate groups," such as "skin heads" in America, Europe, and Russia, can spread their messages of hate in ways that were not previously possible. Hate Speech Whereas the US has tended to focus its attention on controversial Internet speech issues that involve online pornography, European countries such as France and Germany have been more concerned about online hate speech. In 1997, Germany enacted the Information and Communications Act, which was directed at censoring neo-Nazi propaganda. However, the German statute applies only to persons who reside in Germany. Initially, the statute was intended to regulate the speech transmitted by ISPs outside of Germany, as well. Hate Speech (continued) Another controversial form of hate speech on the Internet is one that has involved radical elements of conservative organizations. For example, right-wing militia groups, whose ideology is often anti-federal-government, can broadcast information on the Internet about how to harm or even kill agents of the federal government. Consider the kind of anti-government rhetoric that emanated from the militia movements in the US in the early 1990s, which some believe led to the Oklahoma City bombing. Speech That Can Cause Harm to Others Some forms of hate speech on the Internet are such that they might also result in physical harm being caused to individuals. Other forms of this speech are, by the nature of their content, biased towards violence and physical harm to others. Two examples of how certain forms of speech on the Internet can result in serious physical harm: information on how to construct bombs; information on how to abduct children for the purpose of molesting them. Should such information be censored in cyberspace? Speech That Can Cause Harm to Others (Continued) Recall the Amy Boyer cyberstalking case. Was the posting on Liam Youen's Web site, describing his plans to murder Boyer, an example of hate speech? It resulted in physical harm to Boyer – viz., her murder. Should the ISPs that enable users to construct Web sites that contain this form of speech be held legally liable? Software Filtering Programs as an Alternative to Censorship on the Internet Many believe that filtering also provides a reasonable alternative to censoring speech on the 'Net. Others are less enthusiastic about the promise of software filters as a panacea for resolving the censorship-free speech debate in cyberspace. Software filters can be defined as programs that screen Internet content and block access to unacceptable Web sites. Software Filtering Programs Some filters have been criticized because they screen too much, and others because they screen too little. Filtering out objectionable material through the use of the keyword "sex" could block out important literary and scientific works. For example, it could preclude one's being able to access certain works by Shakespeare, as well as books on biology and health. Filtering schemes that are too broad, on the other hand, might not successfully block non-obvious pornographic Web sites, such as the www.whitehouse.com site. Software filtering programs such as NetNanny are available. Many of these programs have been found to be inadequate. Some Objections to Filtering Not everyone has been impressed with the use of software filters for self-regulatory purposes. Larry Lessig (1999) believes that architectures like PICS (Platform Independent Content) are a form of "regulation by code." He argues that PICS is a "universal censorship system," which can be used to censor any kind of material, not just pornography and hate speech. For example, software filters can be used to block unpopular political speech or dissenting points of view. Objections to Software Filtering (Continued) Rosenberg (2001) motes that filters could also be used by conservative school boards to block out information about evolutionary theory. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) has also recently taken a similar position on the use of filtering. A 2001 ACLU report expressed it fear that using censoring mechanisms such as filters may "burn the global village to roast the pig." Case Illustration: Mainstream Loudon v. Board of Trustees Adult members of the Loudon County public libraries sued the Board of Trustees of the library for what they alleged to be the impermissible blocking of access to Internet sites. The library pointed out that its use of filtering was designed to block child pornography and obscene material. The plaintiffs complained that the filtering devices also blocked access to non-pornographic sites such as the Quaker Home Page, the American Association of University Women, and others. Mainstream Loudon Case (continued) The district court in Virginia ruled in favor of the plaintiffs. It determined that the installation of filtering software on public access computers in libraries violates the First Amendment. But no clear direction was given as to how to resolve the problem. One solution would have been for libraries to provide no Internet access at all. This would not have been a satisfactory alternative for obvious reasons. Mainstream Loudon Case (Continued) Another solution would be for the library to set aside one or more sections for children, in which computer with filtering programs could be provided. Because children are protected under the Child Pornography Protection Act (CPPA) of 1996, it was argued that it would be permissible for libraries to include filtering devices on computers intended for use by children in restricted sections of the library. Defamation in Cyberspace and the Role of ISPs Spinello (2000) defines defamation as "communication that harms the reputation of another and lowers that person's self esteem in the eyes of the community." Defamatory remarks can take two forms: libel, which refers to written or printed defamation; slander, which refers to oral defamation. John Mawhood and Daniel. Defamation (Continued) Tysver (2000) point out that it is not only through words that defamation can occur. For example, a person can be defamed through pictures, images, gestures, and other methods of signifying meaning. A picture of a person that has been scanned and changed by merging another image can also suggest something defamatory. Anyone who passed on such an image could also be held liable by the person filing defamation charges. Our concern here is with defamation involving words. Defamation (Continued) Libelous speech on the Internet can be distinguished from certain kinds of inflammatory speech. Inflammatory remarks made in on-line forums are sometimes referred to as "flames." A person who is the victim of such a remark is described as someone who has been "flamed." But most "flames" do not meet the legal standards of defamation. On-line Flames, as in the case of genuine defamatory remarks, are still problematic. In response to behavior involving flaming, some on-line user groups have developed their own rules of behavior or "netiquette" (etiquette on the Internet). For example, some Internet chat rooms have instituted rules to the effect that any individual who "flames" another member of the group will be banned from the chat room. The Role of ISPs in Defamation In the 1991 case of Cubby, Inc v. Compuserve, the court ruled that Compuserve was not liable for disseminating an electronic newsletter with libelous content. The court determined that Compuserve had acted as a distributor, and not as a publisher, since the service provider did not exercise editorial control over the contents of its bulletin boards or other on-line publications. A different interpretation of the role of ISPs was rendered in the1995 case of Stratton Oakmont v. Prodigy Services Company. There, a court found that Prodigy was legally liable since it had advertised that it had "editorial control" over the computer bulletin board system (BBS) it hosted. The court noted that Prodigy had positioned itself as a proprietary, family-oriented, electronic network that screened out objectionable content, thereby making the network more suitable for children. ISPs and Defamation (Continued) ISPs argued that they provide the "conduits for communication but not the content." This view of ISPs was used in the Zeran v. AOL case in 1997, where AOL was found not to be legally liable for content disseminated in its electronic forums. The Zeran case was the first to test the new provisions for ISPs included in Section 230(c) of theCommunications Decency Act (CDA), which we examined earlier in our discussion of on-line pornography. The 1996 law protects ISPs from lawsuits similar to the one filed against Prodigy. According to the relevant section of the CDA: "[n]o provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider." Defamation and ISPs (Continued) Spinello (2001) argues that simply because an ISP presents an "occasion for defamation" does not necessarily imply that ISP is accountable. Rather, for an ISP to be accountable, two conditions are required: (a) the ISP must also have had some capability to do have done something about the defamation; (b) the ISP failed but failed to take action. Defamation and ISPs (Continued) For Spinello, ISPs are required to take three steps or actions to avoid responsibility: (1) prompt removal of the defamatory remarks; (2) the issuance of a retraction on behalf of the victim; (3) the initiation of a good faith effort to track down the originator so that the defamation does not reoccur. Implications for the Amy Boyer Case Should Tripod and Geocities, the two ISPs that enabled Liam Youens to set up his Web sites about Boyer, be held morally accountable for the harm caused to Boyer and to her family? Should those two ISPs be held morally accountable, even if they were not responsible (in the narrow sense) for causing harm to Boyer and even if they can be exonerated from charges of strict legal liability? It would be reasonable to hold these ISPs accountable if it also could be shown that the ISPs were capable of limiting the harm to persons that result from their various on-line forums.