Ideas

advertisement

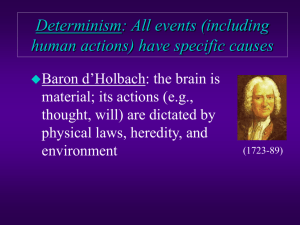

Phil 30302-01 History of Modern Philosophy Spring 2012 Part 2 Professor Marian David 1 Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) • English; famous/notorious for political philosophy: Leviathan • Books banned by Church and Oxford • Author of the Third Set of Objections to Descartes’ Meditations • Radical mechanist and materialist 2 Hobbes • Theory of Ideas (116) – Thoughts are composed of representations / images of qualities of bodies – Imagination is “decaying sense” (≈ mental inertia); memory is roughly the same as imagination – Experience is memory of many things – Materialist theory of Ideas?! • Empiricism (116a, 117, 119b, 121b) – Sensation is the origin of all ideas. – Distinction: Simple ideas vs. complex ideas (117b) – No idea of infinity (121b) – Empiricist account of necessary truths? (121b, 132) 3 • Mechanism (p. 114b) – A living organism = a working machine – But he is not a full-fledged atomist—neither is Descartes, actually • Physical vs. Metaphysical Atomism – Secondary qualities reducible to matter and motion (116ab) – Imagination (memory): a form of “inertia” (117) – Thinking: train of thoughts/imaginations held together by “coherence” (Chap. 3) • In inner words: mental discourse 4 • Reasoning (Chap. 5) – No abstract/general reasoning without words – Reasoning is “reckoning” • can be explained as mechanical computation of symbols (cf. his objections to Descartes) • Hobbes is widely regarded as the great grandfather of the view that the mind is a computer – Reasoning = deductive reasoning, is infallible, when done properly • Spelling out definitions of terms • Induction – Is not even called “reasoning” – Prudence, foresight: prediction and retrodiction “supposing like events will follow like actions” (120b-121a) – Fallible, even when done properly: “but not with certainty enough” (120b, 121a, 126b, 132a) 5 • Knowledge (121a-128b, 132) – Knowledge of fact, by sense and memory (not certain) – Science (philosophy): knowledge of consequences and dependences of facts (certain) • Materialism (129-132, 133-136) – Body = substance; hence “Incorporeal substance” is a contradiction – Spirits are (thin) bodies or nothing because nowhere – See especially p. 133b 2nd – God is the greatest material thing: “I leave him to be a most pure, simple, invisible, spirit corporeal” 6 • Sensation – Mechanistic account of secondary qualities in terms of sensations, which are accounted for in terms of “pressure” • • Friedrich Albert Lange: The History of Materialism (1866) ⇒ Freedom – P. 127a 1st – Concourse Item 4: Hobbes, from Leviathan: “Of the Liberty of Subjects” – Malebranche of freedom, p. 220a – Early Compatibilism 7 Readings for Tuesday, March 6 • Concourse – Item 4: Hobbes, from Leviathan • Malebranche – On Freedom, p. 220 • Spinoza – Intro to Part 2 of Anthology, pp. 111-113 – The Ethics • Read by Definitions, Axioms, and Proposition Headings • Look at text when you want more detail 8 Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677) – Lived in Holland – Jewish, reconverted; excommunicated by his congregation. – Lens grinder – Most important book, posthumous: Ethica Ordine Geometrico Demonstrata – Rather radical rationalist – Axiomatic method universally applied: all explanations, and even ethics, follow with logical necessity from a few axioms 9 Spinoza: The Ethics • There is only one substance – only one truly independent being: God or Nature – look at Descartes’ account of substance in Med III, and Definition V, p. 72b • It is infinite and has infinitely many essential attributes: – only two can be known by us: thought and extension; – So called “individual minds and bodies” are merely different modes of the two essential attributes of infinite substance which is God or Nature. • Everything is in God or Nature – Minds and bodies are two aspects of this one being – Dual Aspect Theory of the mind • Though God is the ultimate ground and explanation of everything, Spinoza was called a “pantheist” and an “atheist” because his God (or Nature) seems to be not personal: – Could one simply replace occurrences of “God” by “Nature”? – A “notational variant” of radical materialism? 10 • God is the only free cause – Everything that happens is necessitated by God’s nature – He is free in the sense: nothing external to Him determines or constrains Him – “Men are deceived in thinking themselves free” (II Prop 35) – “[I]f men understood clearly the whole order of Nature, they would find all things just as necessary as are all those treated Mathematics.” (Spinoza: Descartes’s Principles: Metaphysical Thoughts • Ethics, pages 144-170a; 178 – IV Prop. 4: “The power, whereby each particular thing, and consequently man, preserves his being, is the power of God or of Nature (I P24 Coroll.); not in so far as it is infinite, but in so far as it can be explained by the actual human essence (III P7.). Thus the power of man, in so far as it is explained through his own actual essence, is a part of the infinite power of God or Nature, in other words, of the essence thereof (I P34.).” • Letter to Oldenburg (Sept 1661) 11 Readings for Thursday, March 8 • Leibniz – Monadology – Primary Truths – A New System of Nature 12 Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) • German, trained in law; diplomat, councilor, court historian: “the last universal genius” • Tried to reconcile Protestants and Catholics • Rationalist with more traditional tendencies • Mathematics, Logic, Physics • He is one of the discoverers of the calculus priority quarrel with Newton • Works: mostly letters and notes • Two books: Theodicy; New Essays on Human Understanding 13 Leibniz: Monadology (1714) • Force (vis viva = living force) – L had argued for conservation of “force” or energy (kinetic) against D’s conservation of quantity of motion: modern definition of momentum (see Discourse on Metaphysics, sects. 17-18); New System of Nature, pp. 269-70! – L thinks force will not fit under extension; – It’ll have to go on the mind side of Descartes’ dichotomy. • Monads (unities, ones) – ultimate simple substances, no parts, no extension, hence: – they are minds, having “perceptions and appetites”. – Mentality comes in degrees! – Some monads have “apperception” (consciousness) souls. – Monads have “no windows”: no causal connections between them. – Each monad expresses the whole universe “pre-established harmony”. – Matter is “a well-founded phenomenon” a form of reductionism about matter: material things are “composed” of monads. 14 • Anti-materialism thought experiment: Proposition 17 – “Perception is inexplicable in terms of mechanical reasons” • Necessary vs. Contingent Truths: Propositions 25-37 – Necessary truths (truths of reason, eternal truths) are true in all possible worlds. – Contingent truths (truths of fact) are true in our world but not in all possible worlds. – Knowledge of necessary truths distinguishes us from animals: • Men act like beasts insofar as they rely on induction from observation – Knowledge of necessary truths is attained through reason, through analysis of our ideas; • Basis for science and knowledge of God – Such knowledge is in our rational soul; must be based on innate ideas and principles • Important development in rationalism vs. empiricism debate: – How do we know necessary truths? 15 • Two Great Principles: – The Law of Non-Contradiction • basis for all reasoning about necessary truths: they can be discovered by analysis – The Principle of Sufficient Reason (Props. 36-37) • basis for reasoning about contingent truths. • Arguments for God’s existence: – Cosmological and Ontological. • This world is the best of all possible worlds (53-55) • Pre-established Harmony (Props. 78-81) – Denies mind-body interaction; – Instead, God has set up harmony between psychological and physical laws so that it seems to us as if there were interaction; – The parallel clocks. 16 Readings for Tuesday, March 20 • Newton vs. Leibniz – Pp. 284-303 • Robert Boyle – On the Excellency and Grounds of the Corpuscular or Mechanical Philosophy • John Locke – Intro to Section: Pp. 305-306. – From: An Essay Concerning Human Understanding • Book I • [Book II, Chs. i-xi] 17 Raphael The School of Athens 18 Empiricism vs. Rationalism (rough) • Empiricism – Emphasis on experience as a source of knowledge (Empedocles, Aristotle) • Rationalism – Emphasis on the intellect as a source of knowledge (Pythagoras, Plato) • Empiricism – All knowledge derives from experience – There is no a priori knowledge • Rationalism – There is a priori knowledge – There is knowledge that is independent from experience – And there is quite a lot of it; and it’s important • Radical Rationalism – All knowledge is independent from experience 19 • Empiricism – Medicine, Biology – Common Sense • Rationalism – Mathematics (Geometry); Logic – First principles, axioms – Eternal truths, necessary truths; universal truths; absolute certainty • Debate between Emps and Rats is tied in with debate about Nativism • Nativism a.k.a. Innatism: A priori knowledge is innate – Traditional addition to Rationalism – Rationalism, by itself, is just a negative thesis 20 Nativism • Philosophical debate is about innate information and related issues. • Emps and Rats agree: – Cognitive faculties (sense perception, memory, reasoning) are innate (or have innate basis) • Note that this includes the faculty of reasoning • The debate is about “first principles” • Emps and Rats disagree about: – Innate knowledge, – Innate beliefs & thoughts, – Innate concepts & ideas – Additional cognitive faculty: “intellectual intuition” or “the light of reason” 21 John Locke (1632-1704) • Political Philosophy • British Empiricism – Friend of Newton and Boyle • Most important book: An Essay Concerning Human Understanding – Philosophy & Psychology – Doing for the mind what Newton and Boyle did for matter 22 John Locke: An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689) • Locke’s Program of Empiricism – Announced in Book 1, Chap. II, Sec. 1 • Negative Part: – To argue against the thesis that there are innate principles and ideas. – Book 1, Chap II, Sec. 2 to end of Book 1. • Positive Part: – To explain how we can attain knowledge “by the use of our natural faculties” without the help of innate principles or ideas. – Not a direct argument for empiricism; instead: – Empiricism as a research project → Psychology – Books 2, 3, 4 23 Locke: Against Innate Principles (Book I, Chap II) • Argument in 3 parts – He tends to use the principle of Non-contradiction and the principle of Identity as sample candidates for innate principles (“maxims”) • A: Sections 2-5, 22 – Against argument from universal assent – Against “implicit knowledge” • B: Sections 6-14 – Against: “Innate principles are the principles we assent to when we come to the use of reason” • C: Sections 17-21 – Against: “Innate principles are the principles that are believed and known as soon as they are understood” • Self-evidence innateness 24 • Relation: Innate principles/beliefs vs. innate knowledge? – Often not distinguished – Traditional assumption: truth of innate beliefs is guaranteed because they come from God – Theory of evolution will raise a problem for this assumption • Locke shifts debate from principles/beliefs/knowledge to concepts/ideas: – Ideas are “the materials of knowledge” – No innate knowledge of principles without innate ideas – Locke will argue that there are no innate ideas – His main argument is a “no need” argument – Empiricist psychology of concept formation • Positive part of Locke’s program: 25 Positive Part: Empiricism about Concepts • Locke claims he can explain the origin of our ideas without resorting to innateness (B2, chap I, sec 1); – That is, he says he can explain how we can think the thoughts we can think without resorting to innateness. • Concept EmpiricismB: – All ideas come from experience: from sensation or reflection. – Baby version; B2, chap I, sec. 2 • Experience divided into two forms! – Sense Perception → ideas from sensation – Introspection (reflection) → ideas from reflection • Concept Empiricism prior to Knowledge Empiricism! – Ideas (concepts) make up the contents of thoughts: the “materials of knowledge”. – Locke holds that knowledge empiricism presupposes concept empiricism. 26 Concept Empiricism • Concept EmpiricismB is ridiculously false! – I can think about many things that I have never experienced. – Response: We need to make a division: Ideas Basic “simple” ideas Derived ideas Complex ideas General ideas Relational ideas • The non-basic/derived ideas “come from” experience, but only indirectly, they are generated from simple/basic ideas which come directly from experience. • We have mental faculties (operations of the mind) that generate non-basic ideas from basic/simple ideas (B2, chap XI). 27 Natural Faculties of the Understanding (the mind) 1. Experience Sense Perception → Introspection → ideas from sensation ideas from reflection 2. Memory 3. Reasoning (in a broad sense) Discerning Composing Comparing Abstracting Naming → → → → complex ideas (of modes and substances) ideas of relations general ideas defined ideas, e.g.: unmarried male = bachelor • Natural Faculties are innate! • But no innate ideas! • Book 2, chaps. I, XI, XII.1 28 • Concept Empiricism: All ideas come directly or indirectly from experience – Ideas can be divided into two classes: simple (basic) vs. others. – All simple (basic) ideas come directly from experience, from sensation or reflection: there is no other source of simple (basic) ideas. – All other ideas come indirectly from experience: they are formed from simple (basic) ideas through (repeated) application of our natural (innate) cognitive faculties. • The Chemistry of the Mind • Disagreement with Descartes? – Different conceptions of experience. – Disagreements about various sample ideas. – Locke: Introspection depends on sensation for input ideas; bk 2, chap I, secs. 20-25. 29 Readings for Tuesday, March 27 • Locke’s Essay, Book 2: – Chaps. XII-XIV; – Chap. XXI, Secs. 1-7, 73; – Chaps. XXII-XXIII; – Chap. XXVII, Secs. 1-2. 30 • Empiricist program is committed to concept reductionism: – All concepts can be decomposed into, analyzed, defined in terms of, basic (simple) concepts that come directly from experience. – A very strong claim. 31 Map of Ideas • Taxonomy – See Concourse, Item 5: MapofIdeas.doc • Simple Ideas – Definition at bk 2, chap II, sec 1 • What is given in experience. • Don’t confuse ideas of things and qualities with the things and qualities themselves. • Unfortunately, Locke does sometimes. • “Simple idea/complex idea” doesn’t have to match “simple thing/complex thing” ! – Interesting case: Idea of Solidity (bk. 2, chap IV) – Interesting case: Idea of Power 32 • Complex Ideas: of Modes – ideas of dependencies on, or affections of, substances • no assumption of independent existence – of Simple Modes: space, time, number, infinity • Problem cases: Idea of Number, idea of Infinity – of Mixed Modes: murder, obligation, drunkenness, fencing, a lie,… • Complex Ideas: of Relations • Complex Ideas: of Substances – are “taken to represent distinct particular things subsisting by themselves” (bk 2, chap XII, sec 6) – Interesting case: The idea of God is complex, made from simpler ideas that derive ultimately from experience (chap XXIII, sec 33-37) – Problem case: Idea of Substance 33 Readings for Thursday, March 29 • Locke’s Essay: – Book 3: Of Words • Chaps. III, VI – Book 4: Of Knowledge and Opinion • Chaps. I, II • Leibniz – From preface of New Essays Concerning Human Understanding • Pp. 422-425a 34 Complex Ideas of Substances (Bk 2, Chap XXIII) • Ideas of substances (of things, such as apples) are all complex. – Idea of an apple: ideas A, B, C,… from experience, get bundled together to form the complex idea: [thing that is A and B and C and…] – We suppose that ideas A, B, C,…are ideas of qualities of an underlying thing that has those qualities: a subject, substratum, substance. • The idea of substance or thing itself (sec 1-4). – Try to form the idea of thing itself, as distinguished from your ideas of the various qualities of a thing; mentally subtract the qualities from the thing! • What do you get? …Err? – The idea of a “I know not what”: a confused idea? Not really an idea? – From experience? – Problem for Empiricism? 35 Ideas of Body and of Soul (Bk 2, chap XXIII) • They are ideas of substances (hence, complex ideas) • Body ≈ an extended solid thing ≈ an extended solid substance with cohering parts and the power to communicate motion by impact. • Spirit = Mind ≈ a thinking and willing substance with the power of putting bodies into motion by thought. • Our knowledge of mind and body is equally shallow! – We know that minds think and that they move bodies by willing, but we don’t know how they think and how they move bodies; – We know that bodies cohere and that they move other bodies, but we don’t know how cohesion works and how bodies move bodies through impact. 36 General Ideas (Bk 3) • Language – Communicating our ideas – Representing the world • Generality – We experience only particulars – But most words are general – General terms needed to communicate ideas/knowledge • Information/knowledge is conveyed almost exclusively in general terms. • General Ideas – Words are general when the signify general ideas – General ideas are made by abstraction 37 • Theory of Abstraction – Bk 2, chap XI, sec 9; Bk 3, chap III, sec 1-9 – What is the origin of general ideas? – Crucially needed for empiricism: most knowledge involves general ideas/concepts – General ideas: abstracted by attending to common features and/or by separating ideas from determinations of time and place: “Resemblance analysis” • Conceptualism – Sorts of things (species, genera) are abstracted ideas – They are creatures of the understanding with some foundation in the similitude of things – Against Plato and Aristotle • Problem – How to give an account of abstraction that does not presuppose that we already have some general ideas? – Historically, accounting for generality in thinking has been one of the toughest challenges for empiricism. 38 • Essence – Aristotle: What is this? It is an F. (kind, sort, species) – What is it to be an F? Locke says, that’s an ambiguous question: • What is the definition of F? • What is the inner structure of Fs? • Nominal Essence – An abstracted idea; made by us. – A classification of things on the basis of how we experience them. – Doesn’t trace inner common traits; traces observable similarities. • Real Essence – The inner constitution of a thing on which all its properties and powers depend; – That is, the primary qualities of the parts of a thing (of atoms). – We don’t know much about primary qualities of atoms; we don’t know much about their necessary connections to other qualities. – We don’t know much about the real essences of material substances. 39 Readings for Tuesday, April 3 • Locke’s Essay: – Book 4: Of Knowledge and Opinion • Pp. 386-421 • Leibniz – From preface of New Essays Concerning Human Understanding • Pp. 422-425a 40 Empiricism and the Limits of Knowledge • Physics – Given concept empiricism, we can form ideas about the inner, unobservable structure of matter. – But knowledge empiricism implies that we don’t know much at all about the inner structure of matter; the particles constituting matter are too small for us to observe their qualities and the relations among them: We don’t know much about the real essences of material substances. – That is: though we can think thoughts and ask questions about the real essences of things, we don’t know the answers. – Atomistic physics does not, for the most part, give us knowledge (merely probability). • Isaac Newton 1642-1727: Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (1687) • Gravitation: Mathematically described: But what is it? • Gravitation: Action at a Distance! • Does not fit with strictly mechanistic philosophy • Psychology – Similar limitations for knowledge of our own minds. 41 Knowledge and Opinion (Bk. 4) • Knowledge – Our own ideas are the only immediate objects of our minds: all knowledge must be about them; – Knowledge is the perception of agreement or disagreement of ideas. – Fours sorts: • • • • – • Identity and diversity; Relation; Co-existence or necessary connection of qualities in substances; Real existence Only the last is of particular things; all other knowledge is general Degrees of Knowledge – Intuitive (certain: no doubt possible) – Demonstrative (certain but doubt possible before the demonstration) – Sensitive (lowest level of “certainty”: moral certainty → not really certainty) 42 • General Knowledge = Knowledge of General Propositions – Intuitive • Identity/diversity: White is white; White is not black;… → Axioms of identity and noncontradiction • Relation: 3 is more than 2; 3 is equal to 2+1;… → Axioms of equality and inequality • Coexistence/Non-coexistence: Idea of yellow belongs to idea of gold; Two bodies cannot be in same place at same time;… – Demonstrative • Three angles of triangle equal to two right ones; math theorems; ethical principles • Figure entails extension; Impact entails solidity – [Sensitive • None: because all sensitive knowledge is about particular real existences] • General knowledge is self-evident or demonstrable from what is self-evident by self-evident steps – Self-evident = understanding is sufficient for knowing – It’s all based on the faculty of Discerning 43 • General Knowledge – Does not depend on sense experience, beyond whatever sense experience is required to frame the relevant ideas. – It is about our own general ideas, “only in our minds”: existence neutral (see B4, chap III, sec 31). – It results from innate faculty of abstracting and composing and then discerning our own ideas → Faculty of Discerning!! (Book 2; chap XI). • Unfortunately, there seems to be a problem with this. • Locke is attempting to reduce our knowledge of math, logic (etc.) to knowledge of relations of our own ideas: – Response to Leibniz’s challenge: “Empiricism can’t account for our knowledge of necessary truths” – Locke: Introspection/reflection (discerning of ideas) is a form of experience! • General propositions that are not intuitive or demonstrable are not knowledge – Their knowledge would require experience in addition to experience needed for framing the relevant ideas – Induction yields probable judgment only (≠ knowledge) • Locke was one of the first to seriously discuss evidence and probability 44 • Particular Knowledge = Knowledge of Propositions about Particulars – Intuitive • My own existence • That I presently have idea X – Demonstrative • Only one item: That God exists – Sensitive • Knowledge of external things other than God • Limited to what is directly observed • We have knowledge of existence of external objects “by that perception and consciousness we have of the actual entrance of ideas from them” (B4, chap II, sec 14) • Where X is an idea from sensation: We can have knowledge that there is an object y that causes this idea X of a PQ or a SQ of y; but no resemblance in case of SQ • Sensitive Knowledge – Certain? not really: Sensitive “knowledge” – “Here we are provided with an evidence that puts us past doubting” (Book 4, chap II, sec. 14 (p. 344) – “Moral certainty” 45 Some Worries • Definition of Knowledge – Does not seem to fit all cases • Most basic General Knowledge – Account in terms of agreement/disagreement of ideas is problematic – At best, he accounts for instances of axioms: • How to account for knowledge of axioms themselves? By induction? • Reality of Knowledge? – See Book 4, chap IV 46 Readings for Thursday, April 5 • George Berkeley – Introduction, pp. 435-437 – Three Dialogues Between Hylas and Philonous • Preface • First Dialogue 47 George Berkeley (1685-1753) • Irish; Anglican Priest – Spent time in Newport, RI – Bishop of Cloyne, Ireland • Mathematics, Optics, Theory of Vision, Philosophy • Main work: A Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge (1710) – • Advocates radical Idealism Three Dialogues Between Hylas and Philonous, in Opposition to Skeptics and Atheists (1713): – Berkeley thought that belief in matter leads to skepticism, materialism, atheism 48 Berkeley’s Main Argument 1. Sensible things are those only which are [can be] immediately perceived by the senses. 2. Only sensible qualities (and combinations of sensible qualities) can be immediately perceived by the senses. Hence, 3. Sensible things are (combinations of) sensible qualities. 4. Sensible qualities are sensations, i.e. ideas: they exist only in a perceiving mind; their being is being perceived. Therefore, 5. Sensible things are (combinations of) ideas; they exist only in a perceiving mind; their being is being perceived. • Idealism – – – the view that all things are minds or dependent on minds (ideas) as opposed to Realism, the view that there are things that are independent of minds B himself calls his view “Immaterialism”; that can be misleading. 49 • Setup – B’s rules of debate between Idealism and Realism: Whoever goes more against common sense and/or is committed to Skepticism loses. (p. 456b-57a) – B does not deny principles of science and math; he holds that “universal intellectual notions” are “independent of matter” (p. 457a) • Material things – if defined as “sensible thing”, then B holds there are material things, but they are all bundles of ideas: for them, to be is to be perceived: esse est percipi – if defined as “mind independent” or as “insensible material substratum”, then B holds that there are no material things • Premises 1 & 2: Sensible Things (p. 457) – Immediacy – “The senses make no inference” 50 Readings for Tuesday, April 10 • George Berkeley – Three Dialogues Between Hylas and Philonous • First Dialogue, especially pp. 472b (Hyl. To speak the truth…) to 474. • Second Dialogue 51 Premise 4: Against Realism About Sensible Qualities • 1. Against Realism About [Secondary] Qualities – Heat, Tastes, Sounds, Colors (p. 458-464b) – Three sorts of arguments: • Alleged Qs of a thing can be turned into sensation of pain/pleasure • Relativity of Sense Perception • Absurdity of Q Realism (if sound is motion, sound is felt not heard) • 2. Explaining SQ/PQ divide (p. 464) • 3. Against PQ Realism and against SQ/PQ divide – Extension, Motion, Solidity, Distance (p. 465-472—with interruptions) – Two sorts of arguments • Relativity of Sense Perception • No PQ without SQ 52 • SQs and PQs: – Berk: No fundamental SQ/PQ divide: • Disagrees with Galileo, Descartes, Locke; • Agrees with Aristotle – Berk: All qualities are ideas: • Disagrees with Aristotle • Material Substance/Substratum (p. 469b-471a) – B wants his argument to show that material things exist only as perceived by a mind; for this – he needs to equate: material thing = sensible thing = sensible qualities – Locke holds: material thing = underlying substratum that has/supports qualities – B objects to L’s theory of substance: notion of underlying substratum that supports qualities is meaningless, because not underwritten by experience. 53 • Representational Theory of the Mind – Descartes, Locke – RTM rejects Premise 1: Sensible things are perceived indirectly, via mediating ideas – If “sensible thing” means “sensory idea”, then Premise 1 is true, but B’s conclusion is trivial • Berkeley Against RTM: – Against representation by resemblance – Against representation by causation – Pp. 472b-474; 473-475; 478-84 • Berkeley Against RTM: – RTM leads into Skepticism (p. 473-4, and passim) • The “Perspectives” Argument 54 Readings for Thursday, April 12 • David Hume – Introduction, pp. 509-511 – An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding • Advertisment • Section I, pp. 533b-534a, 536b last para. to end of section • Section II: Of the Origin of Ideas • Section III: Of the Association of Ideas • Section IV: Sceptical Doubts 55 Berkeley’s Idealism: Positive Views • To be is to be perceived or to perceive • No unperceived things? – That would be absurd—radically contrary to common sense. – B’s Response: God’s perception keeps things in being (476b-478; 486b)!! • Berk on Sense Perception: – When I “perceive a material thing X”, what really happens is that God causes me to have an X-idea. – Berkeley ≈ Malebranche without matter. • Worries about Berk on Sense Perception: Identity or Archetype Theory? • How can different people perceive the same thing? – Identity Theory: My idea = God’s idea – Archetype Theory: God’s idea is an archetype of my idea • A version of RTM • Leads to Skepticism 56 • Third Dialogue: Raises and Responds to various objections – Creation objection (p. 497a-500) – Craziness objection • Summaries of Berkeley’s position: – 478a-b; 486a-b; 500b-end • Dispositional theory of unperceived objects: – To be is to be perceivable (497b-498) – Alternative to “God perceives them”? • Skepticism and the Subject/Object divide! – Doing Epistemology via Metaphysics 57 The Enlightenment • 18th century, esp. France & England, until French Revolution (1789) – Anti-Absolutism – Anti Church Anti Religion – Pro Science: “The Age of Reason” • Voltaire – “Letters Concerning the English Nation” Newton, Locke • Deism: Rational Religion • Dennis Diderot & Jean d’Alembert – The Encyclopedia (Influenced by Bayle’s Dictionary) • La Mettrie; Baron d’Holbach – Radical Materialists and Atheists – Man’s unhappiness is due solely to his ignorance of nature (d’Holbach). 58 David Hume (1711-76) • Scottish – Scottish Enlightenment – Friend of Adam Smith • Historian, Essayist, and Philosopher • British Empiricism • Most important book: A Treatise on Human Nature (1739) – Philosophy & Psychology & Ethics 59 Hume: An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1748) • The Science of Human Nature (Section I) – he calls it “moral philosophy” • Perceptions of the Mind (Section II) divided into two classes: – 1. Impressions • Outward impressions (i.e. sense impressions of colors, sounds, etc.) • Inward impressions (feelings, e.g. pain, pleasure) – 2. Ideas • Less lively than impressions: the elements of memory, and imagination—of thoughts other than present experiences • Concept Empiricism: – All ideas are copies of impressions (baby version); – All complex ideas are ultimately composed of simple ideas; all simple ideas are copies of impressions (more serious version). 60 Readings for Tuesday, April 17 • David Hume – Introduction, pp. 509-511 – An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding • Advertisment • Section I, pp. 533b-534a, 536b last para. to end of section • Section II: Of the Origin of Ideas • Section III: Of the Association of Ideas • Section IV: Sceptical Doubts • Locke, Essay: – “Of Power”, bk 2, chap XXI, secs. 1-5; 61 62 63 • The Missing Shade of Blue! – One paragraph, p. 540a-b; – Could you imagine a shade of blue you’ve never experienced? – • A counterexample to empiricism? Concept Empiricism as a tool of Criticism – If an alleged “concept” is not copied from an impression (does not derive from experience) then it is a pseudo concept, a fake concept. – Empiricism as a test of cognitive significance; p.540b. • Association of ideas (Section III) – An attempt to state some psychological laws. – Associationist Psychology 64 Enquiry, Section IV: Skeptical Doubts • Two types of thoughts (propositions): – about Relations of Ideas • Their opposite is impossible (violates the law of non-contradiction). • Intuitively or demonstratively certain: – e.g. mathematical & geometrical truths, – but also trivial truths, e.g.: “All bachelors are unmarried”. • Can be known by “the mere operation of thought”, from analyzing our own ideas. • No factual information about the world (existence neutral). – about Matters of Fact • Their opposite is possible. • Cannot be known by the mere operation of thought. • About the world: factual information. • “Relations of ideas” – Locke/Hume proposal for empiricist account of (our knowledge of) necessary truths. 65 • Granted (if only for sake of argument): Observation and memory give us knowledge of some present and past matters of fact: – of facts we observe now – of facts we did observe in the past and still remember • Question: How do we know about “absent” matters of fact? – Take “absent” here to mean: • facts that we believe exist now, but that we do not observe now; • facts we believe existed in the past but did not observe then; • facts we believe will exist. • Answer: 66 Hume on Causal Inference (Secs IV & V) • Our knowledge, if we have any, of absent (unobserved) matters of fact is based on causal inference: – From observed causes we infer unobserved effects; – From observed effects we infer unobserved causes. • What is the foundation of such causal inferences? • Hume’s claim is going to be: – Causal inference is based on experience not on logic/the intellect/reason (Sec. IV: p. 543) 67 Causal Inference (first try) Event A occurs now. Event B will occur. • (present observation) (prediction) Not a logical (i.e. deductively valid) inference ! – Not a relation of ideas. – A and B are two distinct events. • Causal inference depends on past experience of constant conjunction of events. – When Hume talks about “constant conjunction” think about correlation: events of type A always correlated with events of type B. 68 Causal Inference (second try) Whenever events like A occurred in the past, they were followed by events like B. (memory of past observations) Event A occurs now. (present observation) Event B will occur (prediction) • Is this a logical (deductively valid) inference? – No – What is the principle or rule of Inference? – Not Modus Ponens! – Pages 545b-546a! 69 The Uniformity of Nature (UN) • All causal inference relies on the Principle of the Uniformity of Nature: – The future will resemble the past, or – Unobserved cases behave like observed cases, or – The world is not chaotic, or – Future futures will be like past futures, or… • Different laws of nature are different, more specific, manifestations of the UNprinciple: – All metals expand when heated. 70 Causal Inference (third try: final) • Nature is uniform. Whenever events like A occurred in the past, they were followed by events like B. Event A occurs now. (=UN, by … ?) Event B will occur. (prediction) (by mem. of past obs.) (present obs.) Valid but: – UN is not a logical principle (not a relation of ideas)! – If true, it is a matter of fact, an unobserved (“absent”) matter of fact. • Therefore, it cannot be established by causal inference! – Hume’s circularity argument (sec IV, pp. 546b-548a) – Since UN is an absent matter fact itself, we must go back and put UN into Hume’s argument: see what happens. 71 K of AMFs depends on Causal Inf. depends on Past Experience of Regularities + K of the UN, = since UN = an AMF K of AMF goto top 72 Skeptical Conclusion (“Skeptical Solution”?) • Causal inference is “not based on reasoning or any process of the understanding” (the intellect): he means, it is not deductive. • ↓ We don’t have certain knowledge about any unobserved matters of fact. • But we do constantly make causal inferences! (Sec V, part 1) • Underlying principle is not a principle of the intellect, but a “principle” of human nature, a habit, an animal instinct (pp. 549b-550): – When we have experienced in the past a constant conjunction (correlation) between two types of events, we are determined by habit (custom, animal instinct) to expect an event of the second type as soon as we observe an event of the first type. • Summary so far: 551a 73 “The” Principle of Causation?? • Remember: Relations of ideas vs. matters of fact. • Compare: – PC1: Every effect has a cause. – PC2: Every event has a cause. • Did Descartes confuse the two? 74 Knowledge Empiricism and Concept Empiricism • Locke might say: – Okay, so it follows from Knowledge Empiricism that we cannot know for certain whether A causes B, – but it can still be rational to believe that A causes B; it can be a probable opinion. • Hume responds (see below): – Nope, – not really, – not in the ordinary sense of “A causes B”, – not if Concept Empiricism is true. 75 Hume on the Concept of Causation (Sec VII) • The ordinary concept of causation has two ingredients: – (1) constant conjunction (correlation) between types of events – (2) necessary connection between events (force, power, a must) • What is the origin of our concept (idea) of necessary connection? • Hume: It does not come from experience! • He examines: – Body to body causation – Mind to body causation – Mind to mind causation 76 Readings for Thursday, April 19 • Hume, Enquiry – Section VII: Of the Idea of Necessary Connection – Section XII: Of the Academical or Sceptical Philosophy 77 • He finds no impressions from which the idea of a necessary connection (a must, a force, a power) could have been copied or derived. • Given concept empiricism, it follows that “necessary connection” is a pseudo concept: – It doesn’t derive from any impressions = it doesn’t come from experience = it’s not really a genuine idea/concept = it doesn’t make any sense, it’s just meaningless words • Hence, our ordinary “concept of causation” is defective: “A causes B” means, in our mouths: • (1) A-type events are always followed by B-type events; and • (2) A nuddleduddels B; • Hume offers two replacement concepts, p. 563b: 78 • Humean Causation (1): “A causes1 B” = A is followed by B, and all events like A are followed by events like B – Objective, empirically respectable, scientific: but thin. – Causation as mere constant conjunction (or regular correlation) of events; p. 51. • Humean Causation (2): “A causes2 B” = A is followed by B, and whenever we observe an event like A we expect an event like B. – Thicker but partly psychological: subjective. – It contains our feeling of expectation; p. 51. • Hume holds that the pseudo-concept of a necessary connection results from a confusion: it’s a projection from an inner impression (a feeling of expectation) onto the outer world. 79 Comments on Hume • In action we constantly rely on causal assumptions: – They do not constitute knowledge, according to Hume – Animal instincts • Pavlov’s dog: conditioned response → Behaviorism • Watch out: Even with the ordinary concept of causation replaced by one of Hume’s, the skeptical results from earlier still remain: – “A causes1 B” entails that all events like A are followed by events like B – We can’t know that for certain – But at least it makes sense and we can have probable opinion about it • Inductive inference: – Inference from observed samples to a new case. – Inference from observed samples to a population in general. – Hume’s skeptical arguments about causal inference apply equally to inductive inference. 80 More Comments • Hume ≈ Malebranche minus God. • Humean causation1 suggests a (surprising) response to the problem of interaction: – If causation is just correlation (constant conjunction), why shouldn’t mental events cause physical events, and vice versa, even if mental events are immaterial? • Pairing problem still open: Why does this mental event cause that physical event? • Is causation really nothing more than just correlation (constant conjunction)? Is correlation enough? • Humean causation too thin for real causation? – Causation and correlation – Studying science, you’re being told: correlation is necessary but not sufficient for causation. 81 Enquiry, Section 12: Skepticism About External World • How de we get knowledge about the world? – Hume so far: Skepticism about unobserved (absent) matters of fact. – Hume: Considering the nature of observation, the situation is even worse. – Earlier he granted, for the sake of argument, that observation gives knowledge of “observed” matters of fact, but: • The only things we directly observe (experience) are sense impressions (sense data): – we make tacit causal inferences to external world: we regard our sense impressions as effects of causes outside us – but causal reasoning does not give us knowledge – the situation is especially bad in this case • because the relevant correlations are never observable (594b-595) • General skepticism about external world follows inevitably (pp596-600). 82 Empiricism vs. Rationalism • A dilemma? – Rationalism: hard to swallow (?) • What is this intellectual intuition by which we access first principles? • Can there be a scientific explanation of how the intuition-faculty works? – Empiricism: appears to lead to rampant skepticism. • Not only do we know much less than we thought we did (Locke, Hume); • We are also talking non-sense much more often than we think we do (Hume). 83 Freedom and Determinism – In the Enquiry, Hume applies his results about causation to a number of interesting topics, e.g.: – Section VIII: “Of Liberty and Necessity” – Some background 84 The No-Freedom Argument 1. All events are determined. 2. If all events are determined, then there are no free actions. 3. There are no free actions. • Assumption: All actions are events; that’s obvious. • Note: the issue is not whether some actions are not free. • Distinguish two versions of determinism: – Logical determinism – Causal determinism 85 Freedom and Causal Determinism • Principle of Determinism (causal): All events are causally determined by antecedent events and/or conditions. • Determinism and Prediction: – Determinism implies in-principle predictability • Determinism (alternative formulation): – A complete description of the state of the universe at any time tn combined with all the laws of nature logically entails a complete description of the state of the universe at tn+1. Laplace’s Demon: “We may regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its past and the cause of its future. An intellect which at a certain moment would know all forces that set nature in motion, and all positions of all items of which nature is composed, if this intellect were also vast enough to submit these data to analysis, it would embrace in a single formula the movements of the greatest bodies of the universe and those of the tiniest atom; for such an intellect nothing would be uncertain and the future just like the past would be present before its eyes.”—Pierre Simon Laplace, A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities, 1814. 86 Determinism • Hume, pp. 564b-569b; he says: • We all believe in determinism; especially with respect to human actions: – I perform an action because I want to. – I want to perform an action because I have various desires and various beliefs about how to realize my desires. • Our actions are determined by our motives: – Beliefs & desires (= motives) decisions (intentions) actions • In the same circumstances, the same motives lead to the same decisions which lead to the same actions: determinism. 87 Readings for Tuesday, April 24 • Hume, Enquiry – Sections VIII: Of Liberty and Necessity. – Section VI: Of Probability. • Concourse – Item 4, Thomas Hobbes, “Of the Liberty of Subjects”, Chap. 21 of Leviathan. • Locke, Essay – Of Power; Bk. 2, Chap. 21, Sections 7 to end of chapter. 88 • He finds no impressions from which the idea of a necessary connection (a must, a force, a power) could have been copied or derived. • Given concept empiricism, it follows that “necessary connection” is a pseudo concept: – It doesn’t derive from any impressions = it doesn’t come from experience = it’s not really a genuine idea/concept = it doesn’t make any sense, it’s just meaningless words • Hence, our ordinary “concept of causation” is defective: “A causes B” means, in our mouths: • (1) A-type events are always followed by B-type events; and • (2) A nuddleduddels B; • Hume offers two replacement concepts, p. 563b: 89 • Humean Causation (1): “A causes1 B” = A is followed by B, and all events like A are followed by events like B – Objective, empirically respectable, scientific: but thin. – Causation as mere constant conjunction (or regular correlation) of events; p. 563b. • Humean Causation (2): “A causes2 B” = A is followed by B, and whenever we observe an event like A we expect an event like B. – Thicker but partly psychological: subjective. – It contains our feeling of expectation; p. 563b. • Hume holds that the pseudo-concept of a necessary connection results from a confusion: it’s a projection from an inner impression (a feeling of expectation) onto the outer world. 90 Comments on Hume • In action we constantly rely on causal assumptions: – They do not constitute knowledge, according to Hume – Animal instincts • Pavlov’s dog: conditioned response → Behaviorism • Watch out: Even with the ordinary concept of causation replaced by one of Hume’s, the skeptical results from earlier still remain: – “A causes1 B” entails that all events like A are followed by events like B – We can’t know that for certain – But at least it makes sense and we can have probable opinion about it • Inductive inference: – Inference from observed samples to a new case. – Inference from observed samples to a population in general. – Hume’s skeptical arguments about causal inference apply equally to inductive inference. 91 More Comments • Hume ≈ Malebranche minus God. • Humean causation1 suggests a (surprising) response to the problem of interaction: – If causation is just correlation (constant conjunction), why shouldn’t mental events cause physical events, and vice versa, even if mental events are immaterial? • Pairing problem still open: Why does this mental event cause that physical event? • Is causation really nothing more than just correlation (constant conjunction)? Is correlation enough? • Humean causation too thin for real causation? – Causation and correlation – Studying science, you’re being told: correlation is necessary but not sufficient for causation. 92 Enquiry, Section 12: Skepticism About External World • How de we get knowledge about the world? – Hume so far: Skepticism about unobserved (absent) matters of fact. – Hume: Considering the nature of observation, the situation is even worse. – Earlier he granted, for the sake of argument, that observation gives knowledge of “observed” matters of fact, but: • The only things we directly observe (experience) are sense impressions (sense data): – we make tacit causal inferences to external world: we regard our sense impressions as effects of causes outside us – but causal reasoning does not give us knowledge – the situation is especially bad in this case • because the relevant correlations are never observable (594b-595) • General skepticism about external world follows inevitably (pp596-600). 93 Empiricism vs. Rationalism • A dilemma? – Rationalism: hard to swallow (?) • What is this intellectual intuition by which we access first principles? • Can there be a scientific explanation of how the intuition-faculty works? – Empiricism: appears to lead to rampant skepticism. • Not only do we know much less than we thought we did (Locke, Hume); • We are also talking non-sense much more often than we think we do (Hume). 94 Readings for Tuesday, April 24 • Hume, Enquiry – Sections VIII: Of Liberty and Necessity. – Section VI: Of Probability. • Concourse – Item 4, Thomas Hobbes, “Of the Liberty of Subjects”, Chap. 21 of Leviathan. • Locke, Essay – Of Power; Bk. 2, Chap. 21, Sections 7 to end of chapter. 95 Freedom and Determinism – In the Enquiry, Hume applies his results about causation to a number of interesting topics, e.g.: – Section VIII: “Of Liberty and Necessity” – Some background 96 The No-Freedom Argument 1. All events are determined. 2. If all events are determined, then there are no free actions. 3. There are no free actions. • Assumption: All actions are events; that’s obvious. • Note: the issue is not whether some actions are not free. • Distinguish two versions of determinism: – Logical determinism – Causal determinism 97 Freedom and Causal Determinism • Principle of Determinism (causal): All events are causally determined by antecedent events and/or conditions. • Determinism and Prediction: – Determinism implies in-principle predictability • Determinism (alternative formulation): – A complete description of the state of the universe at any time tn combined with all the laws of nature logically entails a complete description of the state of the universe at tn+1. Laplace’s Demon: “We may regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its past and the cause of its future. An intellect which at a certain moment would know all forces that set nature in motion, and all positions of all items of which nature is composed, if this intellect were also vast enough to submit these data to analysis, it would embrace in a single formula the movements of the greatest bodies of the universe and those of the tiniest atom; for such an intellect nothing would be uncertain and the future just like the past would be present before its eyes.”—Pierre Simon Laplace, A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities, 1814. 98 Determinism • Hume, pp. 564b-569b; he says: • We all believe in determinism; especially with respect to human actions: – I perform an action because I want to. – I want to perform an action because I have various desires and various beliefs about how to realize my desires. • Our actions are determined by our motives: – Beliefs & desires (= motives) decisions (intentions) actions • In the same circumstances, the same motives lead to the same decisions which lead to the same actions: determinism. 99 Hard Determinism (HD): • Affirms 1: All events are determined. Affirms 2: Determinism is incompatible with freedom of action. Concludes 3: There are no free actions. Freedom is an illusion! – A train running along on its track thinking it’s free. – Libet’s Experiment (?) • There is no moral responsibility! – Ought implies Can – Responsibility requires freedom: no freedom no responsibility. • Warning: Do not confuse Determinism (the principle of) with Hard Determinism!! 100 Simple Libertarianism (SL): • Agrees with 2: If all events are determined, then there are no free actions. Rejects 3: There are free actions. Concludes: Not all events are determined. = not 1 According to SL, the Principle of Determinism is simply false: – there are events that are not determined. – In particular, free actions are (or essentially involve) events that are not determined. 101 • A Nasty Problem for Simple Libertarianism: – SL says there are events, namely free actions, that are not determined. – BUT, events that are not determined are random. – AND events that are random are not free actions! • they just happen, • they are not under the agent’s control, • they aren’t really his/her actions at all, • the agent is not responsible for such happenings, • see Part 2 of Hume’s Section 8; – Hence: SL does not allow for free actions after all! – 102 103 Readings for Thursday, April 26 • No new readings. 104 Dilemma • If you believe that our actions are (sometimes) free, then the No-Freedom Argument seems to generate a serious dilemma: • Affirm Determinism → no freedom • Deny Determinism → no freedom • Not good. • Can one get out of this? Can one argue that the dilemma rests on some mistake? • Remember Premise 2 of the No-Freedom Argument: – If all events are determined, then there are no free actions. = – Determinism is incompatible with freedom. • The dilemma presupposes this premise: – Both, HD and SL, accept Premise 2; – they both assume that Determinism and freedom are incompatible. 105 Soft Determinism (SD) Affirms 1: All events are determined. Does not conclude 3 (that there are no free actions), because it Denies 2, that is, it affirms Compatibilism: • Compatibilism: Freedom and Determinism are compatible. • See Hobbes, Locke, Hume. • If acceptable, SD offers a way out of the dilemma because it denies the assumption shared by both horns of the dilemma. • But how could one swallow Compatibilism? • What do we mean by free action? 106 Freedom of Action • I am free ≈ I can do what I want • A free action: an action the agent wanted to perform. • An agent wants to perform an action because she has various desires and various beliefs about how to realize her desires. • Motivation: Beliefs & desires → decisions/wants → intentions to act → actions ☝ unless something intervenes 107 Soft Determinism (SD): A compatibilist account of free actions. – Freedom of action requires only the ability to do what one wants; – This is not incompatible with determinism, on the contrary: – A free action is determined (caused) by the agent’s decision (choosing / wanting) to do it. • Hence, the agent is responsible for it. • See slide 102 for a refinement of this account! – An unfree action is also determined (caused) but by something other than the agent’s decision (choosing / wanting) to do it. • Hence, the agent is not responsible for it. • SD promises a resolution to our dilemma! – Freedom with Determinism. 108 109 • • Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (1651): – See Item 4: contains the first two pages of chapter xxi of his very notorious book. – Already gives a compatibilist account of free action, – a relatively simple one, like the one given above. Locke, Essay, bk II, chap. xxi, sections 7-38: – • Locke’s discussion intended as improvement on Hobbes. Hume, Enquiry, Sec VIII, p. 571: compatibilist account of free actions. – Hume’s account is intended as an improvement on Locke. – Up to p. 569b, he mostly emphasizes how our actions are determined by our beliefs & desires (motives): regular correlations between motives (beliefs & desires) and decisions and actions. – In Part 2 of Sec VIII, he argues that freedom and responsibility require determinism; i.e. that Simple Libertarianism doesn’t work. 110 Soft-Determinism and the Nature of Freedom • SD claims to offer a way out of our dilemma. • But does it give an adequate account of free actions? ↓ • Debate about SD becomes debate over the correct account of free action. • Opponents of SD: – “SD’s compatibilist account of free action is not sufficient: it’s a scam!” – Freedom of action requires more than doing what one wants to do; – It also requires the ability to do otherwise. 111 Objections to SD’s Account of Free Action (first sort): • Locke’s Room: Man in locked room who wants to stay. – He could not have done otherwise, even if he had wanted to → His staying was not a free action. – Intuition says: “If you do what you want to do, you’re free.” Not, Locke says, if you couldn’t do otherwise even if you wanted to. – Locke, bk. II, chap. xxi, sec. 10. • SD’s response: ☟ 112 Enriched SD Account of Free Action: An agent’s action A is free ≈ (1) if she wanted to do A, then she would do A, and (2) if she wanted not to do A, then she would refrain from doing A. • Take this as a refinement of the earlier formulation (slide 97), spelling out what it means to say that a free action is determined by the agent’s decision. – See Hume, Enquiry, p. 571: “hypothetical liberty” • But does this allow for the genuine ability to do otherwise? 113 Objections to SD’s Account of Free Action (second sort): • Induced wants/decisions/desires: – – – – Neuroscientist with remote mind control (Delgado’s experiments) Hypnotist Brainwashing (B.F. Skinner book: Walden II) Drugs Actions determined by “induced” wants/decisions/desires are not free actions. • SD’s response: – These cases aren’t really counterexamples because such persons are not acting based on their own wants: these wants are induced by outside forces. • Opponents response to response: – But if determinism is true, all wants (decisions, desires, etc.) ultimately come from outside forces. What’s the difference? 114 A Basic Worry About Soft Determinism • According to SD, – My so-called “free actions” are determined by my decisions/wants, which are determined by my beliefs & desires, which are determined by my earlier beliefs & desires, which are determined by my character and my genetic makeup, which are determined by…factors outside me, factors over which I don’t have control: • Does this really leave room for genuine freedom of action? 115 Moral (so far) • Free action requires: – the ability to do what one wants (chooses, decides) to do, – and – the genuine ability to do otherwise: the agent’s want (or choice, or decision) must be free. • Freedom of action only if Freedom of will (choice, decision). – Note: Apparently it’s important in this debate to distinguish freedom of action and freedom of will – They are different but, it seems, connected. • This leads to a serious worry ↓ 116 Back to Dilemma? • Do we have freedom of choice / freedom of the will? – Hard Determinism: Nope. – Simple Libertarianism: Nope. • • • • SL says: “Our choices/decisions are not determined.” But then they are random events. Random events just happen. They are not our choices/decisions. – Soft Determinism: Nope. • Try to modify the compatibilist account of free action so that it applies to free choice/will; • You get something absurd. 117 • We have a version of the original dilemma: only this time it’s about freedom of the will. • And since (if) freedom of will is required for freedom of action, we again get the result that there is no freedom of action. We are back where we started. • Or should we embrace SD and swallow its compatibilist account of freedom of action after all? But is that real freedom of action; isn’t it a scam? 118 119 • Compatibilists: 1. Often claim that “free will” doesn’t really make sense; only “free action” makes sense. 2. What do they say about actions done under some threat/coercion? 3. Can they make clear why “unnaturally induced wants/decisions” result in loss of freedom while “naturally induced wants/decisions” do not? 120 Readings for Future Life • Kant – Introduction, pp. 655-660 – Critique of Pure Reason • Prefaces and Introduction, pp. 717-729 121 A priori/A posteriori vs. Analytic/Synthetic • Hume: There is a priori knowledge (of necessary truths) in a sense. – It’s never about matters of fact, only about relations of ideas. – Does not convey information about the world. – Understanding is sufficient for knowing: no experience required in addition to whatever experience is required for understanding the proposition. • Roughly: a reduction of the a priori to introspection. • Discussion tends to focus on necessary truths: – p is knowable a priori → p is necessary – p is necessary → if p is knowable at all, then it is knowable a priori 122 Kant and Empiricism • p is a priori = p is knowable independently of experience. • p is analytic = p’s predicate-concept is contained in its subject-concept. – All bodies are extended. – All bachelors are unmarried. – Doesn’t tell us anything about the world; not informative (relation of ideas). • p is synthetic = p’s predicate-concept is not contained in its subject-concept. – Informative; tells us about the world (matters of fact). • Kant: Is there synthetic a priori knowledge? • Hume, in effect, says No: All a priori knowledge is analytic. – Empiricism after Kant: All alleged “a priori knowledge” is either not knowledge at all (false), or a posteriori (not necessary), or it’s analytic (not informative). • Kant says Yes: – Math – Fundamental principles of metaphysics; e.g. Principle of Causation – Kant wants to explain: How is synthetic a priori knowledge possible? 123