Motherhood and Defeasible Duties to Benefit

advertisement

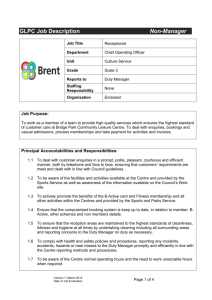

Motherhood and Defeasible Duties to Benefit 1. Introduction A recurring mistake influences discussion of the behaviour of pregnant women and mothers. The mistake in question is the assumption that a mother who fails to do something to benefit her child, either by bestowing some good or by reducing some risk of harm, must be able to provide over-riding countervailing considerations to justify her decision. It is assumed that in the absence of such a justification, the mother is liable for moral criticism. We see this assumption operating in academic literature, medical advice given to mothers, mainstream media and social media. I suggest that this assumption has highly pernicious effects on mothers and on gender equality, contributing to a culture of pervasive guilt and continuous self-sacrifice that both undermines women’s emotional wellbeing and discourages pursuit of career or other nondomestic goals. I attempt to reconstruct the normally implicit reasoning that leads to this assumption and to show that it is mistaken. First, I show that, in treating the mother as required to provide over-riding countervailing considerations to justify a failure to benefit, the discussion assumes that if any action might benefit her child, the mother has a defeasible duty – not merely a moral reason - to perform that action. I suggest that one might be led to assume that the mother has such a duty by implicit appeal to either of two arguments, both of which I show to be initially appealing but unsound. In each case, the initial appeal depends on failure to pay attention to key features of the concept of a defeasible duty. 2. Defeasible Duties and Liability for Moral Criticism To say that someone has a defeasible duty is to make a claim with certain important implications. Consider John Stuart Mill’s observation, “We do not call anything wrong unless we mean to imply that a person ought to be punished in some way for doing it; if not by the law, by the opinion of his fellow creatures, if 1 not by opinion, by the reproaches of his own conscience.”1 Similarly, we should not call something a defeasible duty unless we mean to imply that a person ought to be censured for failure to respond appropriately to it. An agent who has a defeasible moral duty to perform an action is liable for moral censure if she fails to perform the action without being able to provide sufficiently weighty countervailing considerations. When I say that the agent is liable for moral censure, I mean more than that adverse moral judgements would be correct. If the agent is liable for moral censure, then, assuming that no excusing conditions apply, people of appropriate standing may blame the agent. It will also normally be appropriate for the agent to feel guilty. In addition, a defeasible duty makes the agent liable to provide justification: absent conditions that make doing so inappropriate, people with appropriate standing are entitled to ask the agent to justify her behaviour by producing the countervailing considerations. Defeasible duties have these features because of the importance of holding each other to moral standards.2 The behaviour of others matters to us, both because of the immediate effects of such behaviour and because of the attitudes that behaviour implies. This requires not just for us to be able to blame people when they behave badly but also for us to be able to require assurance from others that they haven’t behaved badly when there is reason to think that they may have done so. Thus defeasible duties imply not just liability for blame if the behaviour is unjustified but also liability to be called upon to justify one’s behaviour. 3. Assumptions in the discussion of maternal behaviour John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism, chap. V, sec. 14. There is a significant tradition of attempting to analyse the concept of duty in terms of blameworthiness. This tradition is still very much alive. See, for example, P. F. Strawson, “Freedom and Resentment,” Proceedings of the British Academy 48 (1962): 1–25; Alan Gibbard, Wise Choices, Apt Feelings (Oxford University Press, 1992); Stephen Darwall, The Second Person Standpoint: Morality, Respect and Accountability (Harvard University Press, 2006); John Skorupski, “Moral Obligation, Blame, and SelfGovernance,” Social Philosophy and Policy, Volume 27, Issue 02, July 2010, pp 158-180. I do not want or need to argue that the concept of duty is to be understood in terms of liability for blame. Instead, I claim that failure to comply with a duty implies that blame is appropriate, absent certain defeating conditions. 2 See Strawson “Freedom and Resentment”; David Owens Shaping the Normative Landscape (Oxford University Press, 2012), Chapters 1 and 3; T.M. Scanlon, What We Owe To Each Other (Harvard University Press, 2000) 158-168, for discussion of the importance of holding others to moral standards. 1 2 I will now argue that discussion of maternal behaviour implicitly or explicitly assumes that if any action might benefit her child, the mother has a defeasible duty – not merely a moral reason - to perform that action. The scrutiny of maternal behaviour begins with ubiquitous pressure for pregnant women to regulate their lifestyles, avoiding risky behaviour and embracing healthier alternatives. We are all familiar with the standard advice that pregnant women “can’t” eat a long list of food including unpasteurised cheese, raw eggs, pâté, raw meat, liver etc.3 Pregnant woman are advised to moderate their diet not simply to avoid potential risks but also to actively benefit the foetus. Rebecca Kukla discusses a striking passage from a well-known ‘pregnancy bible’: What to Expect When You’re Expecting warns, “Every bite counts. Before you close your mouth on a forkful of food, consider 'Is this the best bite I can give my baby?’ If it will benefit your baby, chew away. If it'll only benefit your sweet tooth or appease your appetite put your fork down."4 This passage – which regularly incurs the wrath of pregnant woman in chat rooms and on bulletin boards- demands that mothers discipline their eating with literally every bite of food, avoiding the corrupting, selfish bite that is not baby-directed. Here, eating simply because one is hungry ("to appease your appetite") is akin to maternal betrayal.5 The pressure regarding infant feeding after birth is, if anything, even more intense than the pressure for pregnant women to regulate their diets. In the UK, at every visit to her midwife or antenatal clinic, a pregnant woman is bombarded with posters and leaflets reminding her that she must breastfeed to get her baby “off to the best start.”6 Breastfeeding is a recurring topic on parenting social media sites such as Mumsnet and Netmums. This comment from “Amelie W” is typical: “I can't speak for every woman of course but some are lazy and just can't be bothered even though they know deep down it's best “Why should I avoid some foods during pregnancy?” NHS Choices, http://www.nhs.uk/chq/Pages/917.aspx?CategoryID=54 Accessed 3rd September 2014. 4 Murkoff, Eisenberg, and Hathaway, “What to Expect When You’re Expecting”, (New York, Workman Publishing 1985/19886/2002) p. 80. 5 Kukla, “Measuring Motherhood”, International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics Volume 1, Number 1, Spring 2008, p. 81 6 “Off To The Best Start Leaflet”, Start4Life, <http://www.nhs.uk/start4life/Pages/healthcareprofessionals.aspx> 3 3 for their child.”7 Although some commentators will argue that a woman’s reasons not to breastfeed are no one else’s business, the generally unquestioned assumption is that a decision not to breastfeed requires defence and that unless a mother can bring forward weighty extenuating circumstances, she is open to serious criticism if she does not breastfeed.8 The academic literature also assumes that any potential benefits to the child gives rise to a defeasible duty for the mother. Indeed, a significant proportion of the literature suggests that pregnant women have not merely defeasible but absolute duties to avoid any risk to the foetus. According to the duty of care approach, although a woman has a right to choose to abort during early pregnancy, in refraining from doing so she signals her intention to bring the child to term and her acceptance of a duty to ensure a healthy birth.9 On this view, pregnant woman who do not abort have not merely an absolute moral duty, but should also have a legal duty, to eliminate any risk of harm. Moderates like Rosamund Scott respond to these extreme demands by emphasising the defeasibility of maternal duties to benefit. Scott argues that we cannot understand the continuation of a pregnancy as an agreement to undertake all and any sacrifices for the sake of the foetus.10 She says that the mother has a duty to “do all she can” to benefit the fetus, but emphasises that “doing all she can will be doing all those things which she does not have serious reason to refuse to do”.11 Despite her obvious concern for mothers, Scott still appears to endorse the view that potential benefits to the child give rise to a Comment #25 “Why do hardly any women breastfeed anymore” (posted 20-07-14, 11:21 http://www.netmums.com/coffeehouse/general-coffeehouse-chat-514/wine-bar494/1144816-why-do-hardly-any-women-breast-feed-anymore-2.html) 8 For a collection of comments from around the web judging maternal behaviour, including many on breastfeeding, see the “Sanctimommy” site ( https://www.facebook.com/pages/Sanctimommy/523533471000365 ). I thank Rebecca Brione for the link. 7 9 Margery Shaw, “Conditional Prospective Rights of the Fetus”, Journal of LEGAL Medicine. Volume 5 Issue 63 (1984); John Robertson, Legal Issues in Fetal Therapy, 9 SEMINARS IN PERINATOLOGY 136 (1985); John Robertson, The Right to Procreateand In Utero Fetal Therapy, J. LEGAL MED. 3 333 (1982). Rosamund Scott, Rights, Duties and the Body: Law and Ethics of Maternal-Fetal Conflict (Hart Publishing, 2002), p.98. 11 Scott, Rights, Duties and the Body p. 104 10 4 defeasible duty for the mother: she is required to act to secure these benefits unless she has some strong countervailing reason. Discussion of maternal behaviour treats the mother as required to provide over-riding countervailing considerations to justify a failure to benefit and as liable for moral censure if she cannot do so. Given the links between defeasible duties and liability to provide justification, it makes sense to understand this as an implicit or explicit assumption of a defeasible duty to perform each action that might benefit the child.12 I now reconstruct the normally implicit reasoning that leads to this assumption. Why would one be led to assume that a mother has a defeasible duty to perform each action that might benefit her child? I suggest that this assumption implicitly appeals to two arguments, both of which are unsound. 4. Moral Reasons versus Defeasible Duties The first argument starts from (A), the uncontroversial claim that a potential benefit to her child gives a mother a moral reason to act. It then implicitly assumes (B) that if a person has a moral reason to perform some action she has a defeasible duty to perform that action. By making this implicit assumption, we can deduce the mother has a defeasible duty to perform each action that benefits her child from the uncontroversial observation that she has moral reason to benefit the child. (A) If an action will benefit her child, the mother has a moral reason to perform that action. (B) Whenever one has a moral reason to perform some action one has a defeasible duty to perform that action. However, (B) is false. It does not fit with our intuitions about a common set of cases, leaving us unable to account for certain instances of a common and Strictly speaking, I have only argued that if a person has a defeasible duty they are, absent defeating conditions, liable for moral censure. It thus does not follow deductively that discussion that treats pregnant women as liable for moral censure assumes a defeasible duty. The argument is abductive: I suggest that, giving that ascription of duties implies liability for moral censure, the implicit assumption of moral duty is the best explanation for the assumption of liability for moral censure. 12 5 widely recognised moral phenomenon: supererogation. Everyday each of us experiences countless minor cases of supererogation, in which we are not required to act on a moral reason and need not be able to appeal to any weighty countervailing consideration to explain this.13 Suppose that running in a sponsored race for charity would raise a significant amount of money that could then be used effectively to save lives, the training would be on balance good for me, taking up some time but making me feel fitter and healthier. I take it that I have a moral reason to run. Nonetheless, it does not seem to me that I am morally required to run, or liable to moral criticism for failing to run, even if I cannot supply weighty countervailing reasons to justify my failure to do so. It is easy to think of other similar examples. Those who assume that each moral reason gives rise to a defeasible duty are unable to explain such cases. Distinguishing between moral reasons and defeasible duties mirrors the way we think about rationality in general. I need not be subject to rational criticism for failing to do what I have most reason to do. For example, it may be that I have more reason to go for a swim than to do an exercise video – swimming will be more pleasant and give a better overall workout. Yet it seems strange to say that I am in any way rationally required to go for a swim or that I can be criticised as “irrational” if I fail to do so. Joseph Raz calls the claim that we are often rationally permitted to choose between a range of options, “The Basic Belief”. 14 In recognising that moral reasons need not give rise to defeasible duties, we make similar space for a person to fail to do what they have most moral reason to do without being subject to moral criticism. Ben Saunders raises a similar objection against Julian Savulescu’s Principle of Procreative Beneficence, according to which, where selection is possible, parents have a defeasible moral obligation to select the child who, on the basis of available evidence, is expected to have the best life (Ben Saunders, “Is procreative beneficience obligatory?”, J Med Ethics (forthcoming). Published online first 12 February 2014; Savulescu J. “Procreative beneficence: why we should select the best children.” Bioethics (2001,15):413–26). Saunders uses Mother Teresea’s efforts to aid the poor of Calcutta as an example of supererogation. (Saunders, p. 3) I see Mother Teresa’s behaviour as an example of dramatic supererogation which can be explained by those who assume that moral reasons always give rise to defeasible duties. The cases of everyday supererogation described below fit much better with Saunders’ key insight: “refusing to act in a supererogatory fashion does not require special justification” (Saunders, p. 3). 14 Joseph Raz, “Explaining normativity: reason and the will.” In: Engaging reason: on the theory of value and action. (Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 100. 13 6 We should deny (B) the claim that if a person has a moral reason to perform an action, then they have a defeasible duty to perform that action. The first implicit argument is unsound. 5. Duties to benefit S versus duties to perform each action that might benefit S The second argument starts from (A’) the belief that that a mother has a defeasible duty to benefit her child. When discussing a mother’s decision whether to take an action that might benefit her child, people often move without noticing from this uncontroversial belief to the assumption that the mother has a defeasible duty to take the particular action in question because it might benefit her child. The underlying assumption is (B’) that if one has defeasible duty to benefit a person one has a defeasible duty to perform each action that might benefit that person. This gives us: (A’) A mother has a defeasible duty to benefit her child. (B’) If one has defeasible duty to benefit a person one has a defeasible duty to perform each action that might benefit that person. This argument is unsound because it is not clear enough what is meant by the claim that an agent has a defeasible duty to benefit another person. Consider Kant’s distinction between perfect and imperfect duties, as understood by Thomas E. Hill: “Perfect duties come in the form ‘One must never (or always) φ to the fullest extent possible in C’, while imperfect duties, since they enjoin the pursuit of an end, come in the form ‘One must sometimes and to some extent φ in C’.”15 Thus if one has a perfect duty to benefit a person, one must always benefit that person to fullest extent possible in the circumstances. In contrast, if one has an imperfect duty to benefit a person, one must sometimes and to some extent benefit them.16 Hill, Thomas E., 1992, Dignity and Practical Reason in Kant's Moral Theory. Ithaca: Cornell U. P. 16 I am aware that there is some controversy over whether this is the correct way to understand the perfect/imperfect duty distinction as used by Kant. For my 15 7 The perfect/imperfect duty can also be applied to defeasible duties. If an agent has a perfect defeasible duty to φ, then she has a defeasible duty to φ to the fullest extent possible in C; if an agent has an imperfect defeasible duty to φ, then she has a defeasible duty to sometimes and to some extent φ in C. Imperfect defeasible duties to benefit only require agents to benefit the patient sometimes and to some extent, they do not generate a defeasible duty to perform each potentially beneficial action. This means that (B’) is false. The duty in question may be an imperfect duty – and in that case the agent does not have a defeasible duty to perform each action that might benefit the patient. The argument described above is unsound. But there is something close to (B’) that is true: (B’’) If one has perfect defeasible duty to benefit a person one has a defeasible duty to perform each action that might benefit that person. (B’’) can function as a premise in: (A’’) A mother has a perfect defeasible duty to benefit her child. (B’’) If one has perfect defeasible duty to benefit a person one has a defeasible duty to perform each action that might benefit that person. It is thus crucial to establish whether a mother has a perfect duty to benefit her child. As noted above, Rosamund Scott has argued against the view that the special relationship between a pregnant woman and her foetus in a voluntary pregnancy gives rise to a duty to make unlimited sacrifices for the sake of the foetus. This view trades on the thought that in voluntary pregnancy the women would have been able to avoid being subject to such an onerous duty. If she is not prepared to make unlimited sacrifices then she can abort or decline to conceive. Scott argues that this suggestion “ignore[s] the place of pregnancy within our (indeed any) society”, failing to recognise “the acute personal purposes, this controversy is not relevant, given that Hill’s interpretation clearly picks out an important distinction between different types of duty. 8 importance to the woman (and partner) of reproduction”.17 Given the importance of pregnancy to both the state and to individual’s happiness, it is important that women are able to choose to become or remain pregnant without taking on intolerable moral burdens. Scott’s argument can be extended to show that pregnant woman and mothers in general cannot be under a perfect defeasible duty to benefit the foetus. A perfect defeasible duty to benefit would place an intolerable burden on mothers. To understand why the duty in question would be so burdensome we have to think about the nature of pregnancy and motherhood. The first problem is the pervasiveness of opportunities to affect the wellbeing of one’s child. This is most extreme during pregnancy. As Cunningham J. observes in a US Court Case regarding maternal liability for prenatal injury, “As opposed to the third-party defendant, it is the mother’s every waking and sleeping moment which, for better or worse, shapes the prenatal environment which forms the world for the developing fetus. That this is so is not a pregnant woman’s fault: it is a fact of life.”18 Post birth, there is a more separation between mother and child.19 Nonetheless, the mother still faces almost constant opportunities to benefit or harm her child. A second problem is the uncertainty surrounding the risks and benefits to one’s child of many everyday activities. In many cases, it will be unclear how much, if any, risk or benefit an activity poses. There is a sea of conflicting advice about the risks and benefits of many everyday activities during pregnancy from eating peanut butter to swimming. Post-natally, there is controversy about everyday aspects of childcare from how long it is safe to have a small child in a car seat to whether using plug socket covers increase or decrease the risk of electrocution. The combination of pervasiveness and uncertainty mean that a defeasible duty to perform each action that might benefit one’s child would be intolerably burdensome. Such a duty would require constant self-surveillance on the Scott, Rights, Duties and the Body, p. 99 Stallman v. Younquist, 531 NE 2d 355 (Ill 1988). See Scott, Rights, Duties and the Body, p. 98-9. See Kukla, Mass Hysteria, p. 129-130 for discussion of the regulation of pregnant women’s lives. 19 Some of what I say about post-partum mothers also applies to fathers too. I do not focus on fathers here because paternal behaviour does not generally – and certainly has not historically – been under the same scrutiny as maternal behavior. 17 18 9 mother’s part: she would have to be prepared to defend and justify every decision she makes. Moreover, she would have to do so against a background of uncertainty, where little is understood about which activities really are significantly beneficial and about how to weigh up potential risks and benefits. Thus even assessing whether an action is potentially beneficial may require considerable research. The mental and emotional energy required to perform this task is huge. There is also a significant pressure to ‘play it safe’, overestimating potential risk or benefit to the child and underestimating cost to the mother. Given this, a perfect defeasible duty to benefit would have unacceptable implications for women’s self-ownership and wellbeing. If held to such a duty, the mother’s every action over an extended period of time would (a) be supposed to be directed towards the wellbeing of another and (b) be subject to public scrutiny. The mother’s person and body would literally become public property, reduced to instruments to another’s wellbeing. This failure to respect a person’s self-ownership is bad in itself. Moreover, it seems likely to have significant adverse effects on the woman’s wellbeing: given that the demands are so extreme, it is highly likely that the mother will fail to live up to them, producing unwarranted guilt and shame; the very process of trying to meet such standards may be physically and mentally exhausting; finally women who are engaged in a constant battle to meet this duty are likely to miss out on opportunities to do other things that may benefit them in, for example, their careers or other interests. Duties of this kind are unacceptable even if based on voluntarily assumed special relationships – particularly if, as in the maternal case, there is strong reason to limit moral burdens. Thus a mother cannot have a perfect defeasible duty to benefit her child. The revised version of the second argument is also unsound. Conclusion I have suggested that current discussions of maternal behaviour put unjustified pressure on mothers in part because they mistakenly assume that the mother has a defeasible duty to perform each action that may benefit her child. I have 10 reconstructed two arguments that may be implicitly appealed to in support of this assumption and argued that each argument is unsound. 11