930-3518-1-RV - Consortia Academia

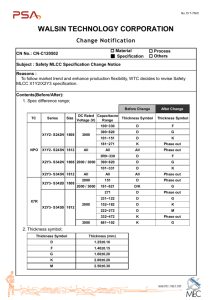

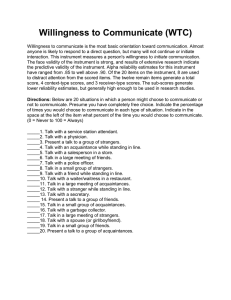

advertisement

Dear Editor, Thank you very much for taking the time to review this manuscript for your journal. The information presented in the body of the paper is an original work, and is not under consideration for publication by any other journal. Should you have any questions regarding the manuscript, please do not hesitate to contact me at either my email address or home address, or by the home telephone number provided below. The title of the paper is Using an iPad for EFL positive self-review: The influence on affective variables. Sincerely, David Ockert, MEd Nagano City Board of Education 39-2-204 Okada Shimo-okada Matsumoto-shi, Nagano-ken Japan, 390-0313 Email: davidockert1@gmail.com Phone: (0081) 263-46-2024 1 Using an iPad for EFL positive self-review: The influence on affective variables David Ockert Nagano City Board of Education 39-2-204 Okada Shimo-okada Matsumoto-shi, Nagano-ken Japan 390-0313 Email: davidockert1@gmail.com Ph / fax: (0081) 246-346-2024 Abstract This paper reports the results of a small-scale exploratory longitudinal study which tested for the influence of a camcorder and an iPad video intervention on self-determination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985) based motives to learn English; and confidence, anxiety, and foreign language willingness to communicate (WTC, McCroskey & Baer, 1985) amongst junior high school students in Nagano, Japan. The survey instruments were administered before and after the two video interventions, arguably a method of video self-modeling (Dowrick, 1976). The results show that the class which received the iPad intervention (n = 22) had an increase in identified regulation (the Ideal L2 Self items; Dörnyei, 2005); intrinsic motives stimulation and accomplishment; confidence, and WTC; and a decrease in anxiety. The results and implications are discussed. Keywords: tablet-computers; EFL; self-determination theory; willingness to communicate; confidence 2 Using an iPad for EFL positive self-review: The influence on affective variables 1. Introduction Research has shown that interventions which stimulate autonomy, competence, and relatedness improve student selfdetermination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985) based motives to study English (e.g. Hiromori, 2006). In addition, Fukada, Fukuda, Falout and Murphey (2011) demonstrated that possible selves (Markus & Nurius, 1986) can be used to increase motivation in university students. These studies show that affective variables - motives, attitudes, perceived competence (aka selfconfidence, Hashimoto, 2002), anxiety - not only play a role in EFL learning, but can be positively influenced by teacher interventions. The purpose of the research undertaken for this study was to test the impact of a video and a tablet-computer, an iPad, intervention on the L2 Learning Experience, the third component of Dörnyei’s (2010) Ideal L2 Self theory, which concerns situated motives related to the immediate learning environment and experience. This paper builds on previous research by the author which has shown strong correlational relationships between in-class iPad use to record students successfully speaking in English in front of class, confidence, anxiety, and WTC, (AUTHOR, 2014) and iPad use and SDT-based motives to study English (AUTHOR, in press). Dowrick (1991) has defined self-modeling as learning that occurs as a result of repeated observations of oneself on edited videotapes that depict only desired behaviors. The research results presented in this paper differ in that the students had the opportunity to view themselves successfully speaking English on one occasion only. Yet, the results of the positive impact that this had on these students is undeniable. Therefore, this paper is amongst the first to examine the use of an iPad to record students speaking in English in front of their peers as an intervening stimulus to influence SDT-based motives, confidence, anxiety, FL WTC and the relationships between them. With tablet computers gaining an ever increasing share of classroom use via various applications, the use of iPad devices can be utilized anywhere with ease. Can teachers use tablet computers as a means to motivate our students? Does recording our students while successfully speaking English positively influence their motives, confidence, and WTC? Will doing so help alleviate their anxiety toward English use? These are questions that this research project set out to answer and the results are quite compelling. 2. Self-determination theory-based L2 motives 2.1 The importance of competence, relatedness, and autonomy Deci and Ryan's (1985) self-determination theory (SDT) focuses on the primary and innate needs for competence, relatedness, and autonomy (Deci, Vallerand, Pelletier & Ryan, 1991). According to Deci and Ryan (1985), the several types of motivated behaviors are ordered along a continuum of self-determination (see Figure 1). In L2 learning research, the SDT based research results point to the importance of motivation from within (Deci & Flaste, 1996), whether defined in terms of intrinsic or integrative motivation (Gardner, 1985). This motivation from within is believed to sustain the learning process more effectively than motivation that is externally regulated or controlled by the teacher and the research evidence thus far supports this view (e.g. Deci et al. 1991; Pintrich & Schunk, 2002; Ryan & Deci, 2000), and the research shows that in order to help our students, educators need to find ways of finding, supporting and maintaining students’ own motivation to learn (Ushioda, 2006). Figure 1. Hierarchical structure of academic motivation based on self-determination theory (Vallerand, 1997) 2.2 SDT-based L2 motivation studies In L2 research, Noels and her associates (Noels, Clement & Pelletier, 1999, 2001; Noels, Pelletier, Clément & Vallerand, 2003) have used SDT-based surveys in FL studies with consistent empirical results. Their work to 'recast' the integrative and instrumental orientations into the SDT motivation framework has helped to “organize systematically many of the reasons for learning a L2” (Noels, et al., 1999, p. 24). The instruments and results presented by Noels and her colleagues have served as the basis for several studies in the JEFL environment (e.g. Yashima et al., 2009). In addition, the relationships between the three psychological needs of competence, relatedness, and autonomy, upon which SDT theory is based, have been shown to have a 3 strong influence on student motivation, a precursor to FL WTC (Nakahira, Yashima, & Maekawa, 2010). 3. WTC, confidence, and anxiety in an L2 3.1 Background of WTC, confidence, and anxiety The construct WTC was first reported on in L1 research by McCroskey and his associates (McCroskey, 1992; McCroskey & Richmond, 1987; McCroskey & Richmond, 1991). Their research shows that WTC captures the major implications that affective variables such as anomie, communication apprehension, introversion, reticence, self-esteem and shyness have in regards to their influence on communicative behavior (McCroskey & Richmond, 1991). Research into WTC has focused on four speaking contexts (public, meeting, group and dyad) and three types of receivers (stranger, acquaintance and friend) (McCroskey, 1992; McCroskey & Baer, 1985). Based on the amount of the preceding affective variables, a student may choose “to enter into discourse at a particular time with a specific person or persons, using a L2” (MacIntyre, Clement, Dörnyei & Noels, 1998, p. 547). 3.2 L2 studies on WTC MacIntyre and his associates (MacIntyre, 1994, 2007; Macintyre & Charos, 1996; Macintyre et al., 1998) have investigated L2 and FL WTC for more than two decades. MacIntyre’s (1994) path model postulates that WTC is a combination of greater perceived communicative competence and a lower level of communication apprehension (CA). The model also postulates that anxiety influences the speaker’s self-perception of competence, and higher anxiety will therefore inhibit WTC via a lower level of self-perceived competence. Building on previous research results, Macintyre and Charos (1996) proposed a model which hypothesized that personality traits and social context have an indirect effect on L2 communication through attitudes, motivation, language anxiety, and perceived competence. Their hypothesis was based on personality traits measured using a survey of global personality traits: extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and intellect. It was shown that these personality traits influenced motivation and WTC, which in turn affected L2 communication frequency. In addition, the social context was measured by a self-report measure and it was found that having more opportunities for interaction in the L2 affects frequency of L2 use directly and also indirectly through perceived competence and WTC. These results support Macintyre et al.’s (1998) belief that context and personality are two of the variables influencing WTC. Figure 2. The heuristic model of variables influencing WTC (Macintyre et al., 1998, p. 547) 3.2.1 EFL studies on WTC Several studies have explored learner’s WTC in an L2 by trying to identify the underlying influences of the variables that precede the act of L2 communication (Hashimoto, 2002; MacIntyre et al., 1998; Yashima, 2002; Yashima et al., 2004). In research by Hashimoto (2002), self-perceived competence and anxiety are precursors to L2 WTC and motivation as based on Gardner’s (1985) model, the latter two variables influencing L2 use frequency. Hashimoto (2002) has added that “perceived competence or self-confidence” (p. 57) in an L2 are positive indicators of motivation. She indicates that they are, in fact, the same construct. In EFL studies on WTC in Japan, Matsuoka (2005) used SEM to show that introversion, motivational intensity, communication apprehension and IP were “significant predictors of L2 WTC” (p. 157). In addition, it was shown “that perceived competence (or self-confidence) and L2 WTC were significant predictors of L2 proficiency” (p. 157). In addition, using a regression analysis on data collected from JHS students, AUTHOR (2012) found that confidence was “the strongest indicator of WTC” (p. 174), while anxiety was a strong negative indicator as well. Therefore, since both motivation and WTC are consistently 4 shown to be predictors of L2 proficiency and use, the present study will test to see to what extent an iPad intervention has on SDTbased motives to learn English and WTC in English based on self-report measures. 3.2.2 Recent developments in WTC research MacIntyre (2012) has recently described “currents and waves” (p. 12) of L2 WTC. These are ‘trends’ toward WTC in an L2, which occur in a student’s mind as they decide whether to speak or not. By examining WTC on multiple timescales within the class room, he describes the following four ‘waves’: • What will other students think, will they tease me for getting it right or laugh at me for getting it wrong (a wave of social comparisons)? • Will I be embarrassed in front of the teacher (a wave of personal pessimism)? • I think I know the answer to the question; maybe I should try (a wave of self-confidence)? • Does someone else know the answer to the question (a wave of isolation)? (p. 15) All of those influences and more will converge and have an impact on whether a student will choose to put their hand up to answer the question or avoid volunteering a response. He also describes the ‘waves’ that a student might experience regarding the WTC “to a second language speaker in a public context, for example someone who stops to ask for directions” (p. 15). These include: •There might be the question about where the conversation is going to go (a wave of anxiety) •Whether the student’s response might be misunderstood (a wave of concern for the tourist) •Whether somebody with better second language skill might be able to help instead (a wave of social comparison) •What if the helper makes a mistake or uses poorly chosen vocabulary (a wave lacking self-confidence)? (p. 15) 3.3 Confidence as a precursor to WTC It has long been understood that confidence is a precursor of WTC in an L2 (see MacIntyre et al., 1998). In the Japanese English as a foreign language (JEFL) learning context, the influence of motivation (based on Gardner and Lambert’s (1972) items for motivational intensity and desire), and confidence led to L2 use via WTC amongst high school students has been shown (Yashima, Zenuk-Nishide & Shimizu, 2004). Yashima and her associates (Yashima, 2000, 2002; Yashima et al., 2004) have conducted research in the JEFL context on affective variables and FL WTC. Yashima (2000) has reported on the relationships between language learning orientations and motivations of Japanese college students and the influence of international posture (IP) on confidence, foreign language willingness to communicate (FL WTC) and L2 learning motivation (Yashima, 2002). Furthermore, attitudes, affect, and WTC were found to influence second language communication amongst EFL students studying abroad (Yashima et al., 2004). 3.4 Anxiety as a precursor to WTC In a second language (L2) study on anxiety and English language use, Woodrow (2006) found that “two types of anxious language learner emerged; retrieval interference and skills deficit” (p. 308), which would indicate that perceived competence and self-confidence would be negatively influenced as well. In addition, “the results indicate that the most frequent source of anxiety was interacting with native speakers” (p. 308). In their study on the relationship between communication confidence, WTC, and the classroom environment, Ghonsooly, Fatemi, and Fadafen (2013) report that “correlational analyses also indicated that willingness to communicate is positively correlated with classroom environment and perceived communicative competence, and negatively correlated with communication anxiety” (p. 1). These results support those found by other researchers reported herein with the important addition that what occurs in the classroom environment can influence students’ affect. Yashima et al. (2009) also demonstrated that anxiety and self-determination theory’s (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985) intrinsic motives are precursors to, and therefore influence, WTC. 4. Using technology to influence student affective variables 4.1 Video self-modeling There are two types of Video Self Modeling (VSM; Dowrick, 1976). The first, Feed Forward, “refers to video images of adaptive behavior that has not yet been achieved. These are created by editing together components of skills already available…These elements can be videotaped separately and edited together into a novel, competent video image” (“VFP”, p. 5, n.d.). Dowrick (1977, in Markus & Nurius, 1986, pp. 961-962) used this type of video recording as an ‘intervention’ in which students with severe psychomotor impairments were asked to perform a task that was beyond their ability level. Participant ‘errors’ were removed during the editing process. The viewing of the successful completion of the tasks was shown to enhance the future performance of the participants. Another variation of VSM is known as Positive Self-Review (PSR; “VFP”, p. 5, n.d.). In PSR, the participants view themselves successfully completing a target behavior with the goal of reinforcing the behavior (Dowrick, 1991, 1999.) The results presented in this paper are amongst the first to report the use an iPad as an intervening PSR 5 stimulus to positively influence student amotivation and SDT-based motives to study EFL. 4.1.1 JEFL studies on table-computer use in the classroom There have been relatively few studies involving tablet computers in the classroom. However, after experimenting with the use of an iPad in the classroom, Brown, Castellano, Hughes and Worth (2012) found that “The data indicate that this particular tablet, the Apple iPad, offered benefits such as speed, video viewing and versatility. However, data also showed that its usefulness depended on the task” (p. 207). For the present study, students were video recorded with an iPad while giving a short ‘quiz’ to their classmates. This allowed some of them to view their successful performance at a later time. Previous research has shown that iPad use has a powerful effect on WTC via confidence (AUTHOR, 2014). Furthermore, SDT motives have also been shown to be influenced by an iPad intervention (AUTHOR, in press). The research presented in this paper explores specifically what, if any, influence the iPad intervention in the classroom has on the relationship(s) between student SDT motives, anxiety, confidence, and WTC. 5. SDT-based research on video game motivation 5.1 SDT research studies on Ideal Selves and video game use Przybylski and his associates (Przybylski, Weinstein, Murayama, Lynch, & Ryan, 2012; Przybylski, Rigby & Ryan, 2010; Ryan, Rigby & Przybylski, 2006) have investigated the relationship between the Ideal Self and video game use using a selfdetermination theory-based model, which focused in particular on the ‘motivational pull’ of video games. For example, Przybylski, Rigby and Ryan (2010) investigated how video games may put players “in touch with ideal aspects of themselves (and how this) is associated with the games’ motivational appeal” (p. 74). They “found evidence that convergence between people’s experience of themselves during play and their concept of their ideal selves was related to enjoyment of play and positive shifts in affect” (p. 74). They believe that “The results of our work make clear that humans are drawn to video and computer games at least in part because such games provide players with access to ideal aspects of themselves; such access, in turn, can have short-term effects on emotion” (Przybylski et. al., 2012, p. 75). 5.1.1 Parallels between PSR with tablet-computer use and video game use As shown by the previous studies, the students’ viewing of their successful use of English via the iPad parallels the psychological satisfaction of the successful completion of a video game activity. This may be due to the fact that, “Increasingly, intervention-focused researchers are demonstrating that games can positively influence both psychological and physical wellbeing” (Przybylski, Rigby & Ryan, 2010, p. 154). There are various reasons for the psychological appeal of video games, not the least of which are the need for competence, autonomy, and relatedness – the three pillars of SDT. Studies have shown that there are changes in the human brain as a result of engaging in activities that are self-determined (see Murayama et al., 2014). There are parallels between game use and tablet computer use for PSR. For example, Can the use of an iPad to record students speaking in English and allowing the same students to view themselves successfully speaking English also support the need for competence, autonomy, and relatedness? Research has shown that the effect of the hormone dopamine has a strong and positive effect on the humans as a result of successfully completing a task (Murphey, 2011) in addition to other changes in the brain (see Murayama, Matsumoto, Izuma, & Matsumoto, 2010). Furthermore, research on achievement goals shows similar results for a neural basis in the cognitive reward system (see Murayama, Elliot, & Friedman, 2012). 5.2 JEFL studies involving video use and motivation In the JEFL learning situation, the results of research studying changes of student affect by Takiguchi (2002) shows that real-time communication with students in foreign countries using a video conferencing telephone system (e.g. Skype or Gizmo) via the Internet improved student interest, concern, and desire (WTC). Takiguchi (2002) carried out a research project testing for changes in affective variables of Japanese elementary students who used VoIP software to communicate with NESs. His results have shown that real-time, in-class communication with students in foreign countries using a voice over Internet protocol (VoIP) conferencing system (e.g. Skype or Gizmo) improved student interest, concern, and desire. Furthermore, the use of Skype has been shown to enable students at schools in various regions around the world to communicate. In addition, research in JEFL classrooms has focused on the use of digital video to promote communication (Foss, 2008; Rawson, 2008), increase student motivation (Shrosbee, 2008), and confidence while speaking (Wyers, 1999, in Shrosbee, 2008). In recent research (AUTHOR, 2014) found that JHSs who were video-recorded using an iPad tablet computer responded favorably, with noticeable improvement in affect. For example, 6. Objectives of the present study The purposes of the present study are to examine the relationships between the SDT factors, WTC instrument subsections, and the three questions on the influence of a video camcorder or iPad use. Analysis will help determine what, if any, causal relationships exist between the SDT, WTC and video and iPad-related survey questions. After reviewing the results of the 6 first iteration of the surveys (see AUTHOR, 2012, p. 174, Table 4) and previous research results, four research questions motivate the present study: 6.1 Research questions: 1. Will the use of the iPad to record students while successfully speaking English increase their SDT-based motives enough to influence their WTC in English? 2. Will the use of the iPad to record students while successfully speaking English increase their confidence and SDT-based motives, in particular their L2 Selves, leading to an increase in WTC in English? 6.2 Hypothesis: 1. The use of an iPad for PSR in the classroom will positively influence student intrinsic motivates, confidence, WTC, and lower their anxiety. 2. The correlation analysis will show strong positive relationships between questions regarding the iPad use, confidence, and WTC, and a negative relationship with anxiety. 7. Method 7.1 Participants Both the pre- and post-intervention surveys for this study were filled out by students in four classes (N = ???) of Japanese junior high school students in a single school in Nagano City, Japan. These four classes were divided into six smaller groups for English classes with the goal of producing six classes of equal ability (classes A, B, C, D, E, and F); there was no discernible difference in ability between the boys and the girls in any class before or after forming the six classes (C. Kitamura, pers. comm., April, 2012). The surveys were filled out during the final semester of the students second and third years, respectively. Each class had a different Japanese teacher but the same ALT. The data reported in this paper are for the students who participated in the iPad intervention (class B) and another class which had no intervention (class A). The other participant data is not presented for comparison since it is of no value for interpreting the data reported herein, and would simply cloud the readers understanding of the results. Course lessons covered the same text material. 7.2 Materials Two self-report measures were used for the first iteration before and after the intervention and a third survey on camcorder / iPad use was also used for the second iteration after the intervention (see Appendix C). The SDT survey, which was based on Yashima et al. (2009), and a WTC survey based on Matsuoka (2005) were used for both iterations. All surveys used the back translation method and were checked by bilingual native Japanese speakers for clarity to ensure comprehensibility for JHS students. 7.2.1 The SDT instrument A Japanese version of the amotivation, extrinsic motivation, and intrinsic motivation sub-scales of the Language Learning Orientations Scale (LLOS; Noels et al., 2000) was used for this research. This instrument has been well validated and widely used in language learning research and the results reported in the literature, in both English (Noels et al., 2000) and Japanese (Yashima et al., 2009). The scale items present a variety of statements representing different reasons for learning English based on the motivational orientations outlined in SDT (Deci & Ryan, 1985). The instrument consists of 21 Likert-type items. The students read each statement and rated each of them from 1 (That is not applicable to me at all) to 6 (That absolutely applies to me). Appendix A presents the English version of the SDT survey, which includes the item level descriptive statistics and scale level Cronbach’s alpha from the first iteration of the instruments. 7.2.2 The WTC instrument The WTC instrument consists of three scales. These scales have been validated and used in EFL research studies in Japan and the results reported in the literature (see Matsuoka, 2005; Author, 2012, 2014a, 2014b). The first tests for confidence (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94) and asks the students to rate 30 scenarios related to using English in various circumstances from 1 (I absolutely don't think I could do that) to 6 (I think I could do that easily). The second scale tests for anxiety (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.96) and asks the students to rate the same scenarios from 1 (I would definitely not be nervous) to 6 (I'd be extremely nervous). The third scale, for WTC (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93), asks the respondents to rate the same scenarios from 1 (If I could, I'd run away!) to 6 (I would absolutely want to try that!). The instrument and sub-scale reliability estimates and item descriptive statistics are provided in Table 5. Please note that the confidence and WTC scales work in tandem, and in contrast with the anxiety scale, a high score is ideal; for anxiety, a low score is ideal. The third survey asked a question each on confidence, anxiety, and WTC in relation to having been recorded with either a camcorder or the iPad. Appendix B presents the English version of the WTC survey, which includes the item level descriptive statistics from the first iteration of the instruments. 7.3 Procedures 7 The surveys were both filled out in pencil during regular class time. The SDT and WTC instruments were filled out for the first time in March, 2011. These two surveys and a third survey consisting of questions regarding the use of in-class video were administered again in March, 2012. During their third year, each class received similar teaching methods, lesson plans and classroom activities. However, only nine class B students were individually video-recorded with an iPad and five were able to view their ‘performance’(i.e. PSR). The results presented in this research study are of the two classes that served as the experimental and control groups and participated in both survey administrations. 7.4 Project outline The fifteen-month schedule of the project can be seen in Table 1. The project proceeded as planned, except that the original plan to use video was changed from the use of a video camcorder to an iPad. Class A had no in-class video taken; Class B students were filmed with a camcorder and also nine of students had filming and self-viewing (PSR) with an iPad. During the months of July and August, 2011, it became evident that the use of a digital video camera and the iMovie software for editing was simply too time-consuming. This was due to our not using a tripod and filming the entire class of more than twenty students. As a result, the face recognition technology was seriously bogged down. As a result, it was decided to use an iPad for the simple convenience of using it in class to record and for instant playback. Class A had no in-class video taken; Class B had individual filming and selfviewing using an iPad. Therefore, class B is the experimental group and class A serves as the control group. The iPad video was taken on January 18th and the PSR occurred on February 28th. Table 1 The Research Project Schedule Jan - Mar 2011 Apr - Jun 2011 July - Aug 2011 Jan - Feb 2012 March 2012 Activity 1. Students fill in the SDT and WTC surveys 1. Video filming in class with a camcorder 1. Video filming in class with a camcorder 1. Video filming in class and replay with an iPad 2. Students fill in the SDT, WTC & new surveys Classes Class A, B Class B Class B Class B Class A, B 8. Results and discussion 8.1 Changes on the SDT scales For the purposes of this research, a decrease in amotivation, extrinsic regulation and introjected regulation is desirable. Furthermore, an increase in identified regulation and the three intrinsic motivation sub-sections would be desirable. As can be seen in Table 2, only class B had a decrease in amotivation, extrinsic regulation and introjected regulation. There was an increase in both IM accomplishment and IM stimulation, while IM knowledge shows a decrease. None of the mean scores for class B after the intervention are the highest; however, the greatest and statistically significant increase in identified regulation and IM accomplishment occurs for class B. These results for class B are excellent. For comparison, class F shows an increase in amotivation and a decrease in all of the six motives. Table 2 Changes on the SDT Scales before and after the iPad Interventio n Amotivation External Introjected Regulation Regulation Class A Before (n = 23) 2.26 (1.48) 2.67 (1.37) 3.04 (1.30) After (n = 22) 2.03 (1.01) 3.20 (1.51) 3.29 (1.42) Change -0.23 0.53* 0.25 Class B Before (n = 18) 2.61 (1.23) 2.74 (1.35) 3.22 (1.22) After (n = 22) 2.43 (1.32) 2.48 (1.42) 2.65 (1.56) Change -0.18 -0.26 -0.57** Identified Regulation Intrinsic Knowledge Intrinsic Accomplish Intrinsic Stimulation 3.84 (1.57) 3.92 (1.38) 0.08 3.32 (1.32) 3.27 (1.49) -0.05 3.01 (1.09) 3.17 (1.43) 0.16 3.43 (1.41) 3.20 (1.48) -0.23 3.63 (1.19) 4.05 (1.37) 0.42 3.04 (1.10) 2.81 (1.41) -0.23 2.57 (1.02) 3.14 (1.34) 0.57* 2.67 (1.13) 2.89 (1.26) 0.22 Note. Mean (Standard Deviation); *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (2-tailed) 8.1.1 Changes on the WTC scales The results of the two WTC survey iterations are compared in Table 3. As can be seen, class B shows a statistically significant change on all three scales. Confidence has increased almost half a point, while WTC has increased by a quarter of a point. Furthermore, anxiety has decreased by a third of a point. These results are not seen in any of the three other classes. In fact, confidence and WTC decreased for class A, in addition to showing an increase in anxiety. 8 Table 3 Changes on the Confidence, Anxiety, and WTC Scales before and after the iPad Intervention Confidence Anxiety Class A Before (n = 23) 3.21 (1.62) 3.50 (1.77) After (n = 21) 2.96 (1.65) 4.08 (1.66) Change -0.25* 0.58** Class B Before (n = 18) 2.55 (1.46) 3.84 (1.79) After (n = 19) 2.96 (1.87) 3.50 (1.78) Change 0.41** -0.34** WTC 2.89 (1.50) 2.64 (1.66) -0.25* 2.24 (1.31) 2.49 (1.77) 0.25* Note. Mean (Standard Deviation); * p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (2-tailed) 8.1.2 The SDT and WTC instrument scale correlations A correlation analysis was performed to test for relationships between the four SDT factors, confidence, anxiety, WTC, and the three questions corresponding to iPad use. These results are shown in Table 4. For the SDT factors, strong correlations exist between iPad use and the extrinsic and identified regulation factor. There are strong correlations between iPad use and both confidence and WTC; and a strong negative correlation between iPad use and anxiety. Therefore, it will be important to watch out for multicollinearity by checking the variance inflation factor (VIF) in the structural equation models (SEM) tested (see Field, 2009). Table 4 The Post-Intervention SDT Motives, Confidence, Anxiety, WTC, and iPad Scales Correlation Matrix for Class B Amotiv External Introjected Identified IM IM IM Regulation Regulation Regulation Know Accom Stim External Regulation -0.55* Introjected Reg. -0.72* 0.80* Identified Reg. -0.48* 0.91* 0.91* IM Knowledge -0.42* 0.90* 0.83* 0.94* IM Accomplishment -0.27 0.61* 0.81* 0.81* 0.83* IM Stimulation -0.21 0.77* 0.75* 0.88* 0.94* Confidence Conf Anx 0.90* 0.13 0.58* 0.22 0.50* 0.60* 0.27 0.65* -0.44* 0.28* 0.08 -0.19 -0.30* -0.16 -0.44* -0.86* WTC 0.19 0.56* 0.43* 0.67* 0.70* 0.66* 0.82* 0.80* -0.71* iPad 0.07 0.43* 0.12 0.33* 0.35* 0.06 0.44* 0.87* -0.77* Anxiety WTC 0.65* Note. *p < 0.01 (2-tailed) 8.2 The Results of the SDT Integrated Regulation items: Ideal L2 selves Of particular interest are the three identified regulation sub-section items: Because I want to be a person who can speak a foreign language is the highest ranked item based on mean score (4.09); Because I want to be a person who can speak English (3.91); Because I think it is important for my personal development (3.45). These are the three highest ranked items, respectively. This evidence indicates that Dörnyei’s Ideal L2 Self System may be the appropriate motivational framework within which to interpret these results. In addition, since there are several means to stimulate student L2 Ideal Selves, the use of the factor containing these items as a stimulus for other variables is strong. 8.3 Research questions and answers 8.3.1 Research question one and answer The first research question asked: Will the use of the iPad to record students while speaking English increase their motives enough to influence their WTC in English? Class B overall had a decrease in amotivation, extrinsic regulation, introjected regulation, and IM knowledge, but an increase in identified regulation, IM accomplishment and IM stimulation. There was an increase in both IM accomplishment and IM stimulation, while IM knowledge shows a small decrease. Based on the correlation analysis results, we can see that strong relationships between IM accomplishment, IM stimulation, confidence, and WTC exist. 9 Furthermore, there are strong correlations between the iPad use and IM stimulation, confidence, and WTC. Somewhat weaker correlations can be seen between iPad use, IM knowledge and the identified regulation (the Ideal L2 Self) items. A strong, negative correlation exists between anxiety and IM stimulation, IM confidence, and WTC. 8.3.2 Research question two and answer Research question two asks: Will the use of the iPad to record students while speaking English increase their confidence via motives – particular their L2 Selves, leading to an increase in WTC in English? The research results show that class B had the greatest increase in identified regulation. Only class B showed an increase in confidence and WTC, and a lower level of anxiety. It could be interpreted that the use of video was a causal variable in this outcome. 8.4 The hypotheses and answers 8.4.1 Hypothesis one Hypothesis 1 stated: The use of an iPad for PSR in the classroom will positively influence student intrinsic motivates, confidence, WTC, and lower their anxiety. The students in class B report a greater increase in IM accomplishment and stimulation, but a decrease in IM knowledge. However, they also had a statistically significant increase in identified regulation (Ideal L2 Selves. As expected based upon results reported elsewhere, a strong correlation exists between the iPad use, confidence, and WTC (see AUTHOR, 2014). This indicates that recording students with an iPad and allowing them to view themselves speaking English increases their confidence, which leads to a greater willingness to use English, at least in the hypothetical scenarios provided on the WTC instrument. 8.4.2 Hypothesis two The second hypothesis stated: The correlation analysis will show strong positive relationships between questions regarding the iPad use, confidence, and WTC, and a negative relationship with anxiety. This hypothesis appears to be correct for class B overall and the boys in particular, especially with regard to anxiety. The SEM results indicate that a beta weight for a given predictor variable (Video / iPad use) is the predicted difference in the outcome variable (on WTC via confidence) in standard units for a one standard deviation increase on the given predictor variable when all of the other predictor variables are held constant. 9. Conclusions This study has several implications for teachers. One is that by increasing perceived competence or self-confidence and reducing language anxiety, student WTC may increase. Creating a motivating classroom atmosphere to reduce anxiety and working to increase student confidence may be effective in increasing WTC and therefore frequency of L2 use in general with Japanese JHS EFL students. The use of the iPad had a direct and strong influence on confidence, which in turn had a powerful influence on FL WTC. Therefore, using table computers such as an iPad to record students may be especially effective with Japanese EFL students to increase their confidence and lower anxiety to use English. The author believes that future, longitudinal studies which track student progress based on gender, orientations, WTC, confidence, anxiety, and their effort / desire to learn English would be beneficial. There are several limitations to the present study. First, the students in class B only had one opportunity for PSR with the iPad. It has been suggested by others in the field that both multiple PSR opportunities followed by a survey of the students would be of greater value in assessing the impact of PSR and student affect over an extended period of time. Second, the student participants in this study were from a single school, and therefore the results may not be assumed to be representative of JHS students in Japan in general. Finally, and perhaps most significantly, only male students were recorded with the iPad and engaged in PSR. This does not allow us to make comparisons on what, if any, differences exist between male and female students at this time. Future studies conducted on a larger scale and track students by gender would be of value to answer whether or not the use of a tablet computer for PSR of the successful use of EFL would benefit educators in both Asia and around the world. Acknowledgments The author would like to thank the students and teachers of Sairyo JHS who participated in this research project; Justin Tong for proofreading the manuscript; and the members of JALT, as this project was made possible with the aid of a JALT Research Grant. Any errors are the author's. Author Biodata AUTHOR has worked in Japan from K to graduate-level business courses at multi-national corporations. His research interests are in the effects of technology in the classroom on motivation, orientations, WTC, and CLT (TBLT). He has a MEd from Temple University and a JLPT Level 2 certificate. References Brown, M., Castellano, J., Hughes, E., & Worth, A. (2012). Integration of iPads into a Japanese university English language curriculum. The Jalt Call Journal, 8(3), 197–209. 10 Deci, E. L., & Flaste, R. (1996). Why we do what we do: Understanding self-motivation. New York: Penguin. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum. Deci, E., Vallerand, R., Pelletier, L., & Ryan, R. (1991). Motivation and education: The self-determination perspective. Educational Psychologist, 26(3), 325-346. Dörnyei, Z. (2010). Researching motivation: From integrativeness to the ideal L2 self. In S. Hunston & D. Oakey (Eds.), Introducing applied linguistics: Concepts and skills (pp. 74-83). London: Routledge. Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2009). Motivation, language identities and the L2 Self: A theoretical overview. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.) Motivation, language identity and the L2 Self (pp. 1-8). Bristol: Multilingual Matters. Dowrick, P. W. (1976). Self modeling: A videotape training technique for disturbed and disabled children. Doctoral dissertation, University of Auckland, New Zealand. Dowrick, P. W. (1977). Videotype replay as observational learning from oneself. Unpublished manuscript, University of Auckland. Dowrick, P. W. (1991). Practical guide to using video in the behavioral sciences. New York: Wiley Interscience. Dowrick, P. W. (1999). A review of self-modeling and related interventions. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 8, 23–39. Foss, P. (2008). YouTube.com video reviews. The Language Teacher, 32(4), 14-15. Fukada, Y., Fukuda, T., Falout, J., & Murphey, T. (2011). Increasing motivation with possible selves. In A. Stewart (Ed.), JALT2010 Conference Proceedings (pp. 337-349). Tokyo: JALT. Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitudes and motivation. London: Edward Arnold. Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. (1972). Attitudes and motivation in second language learning. Rowley, MA: Newbury House. Ghonsooly, B., Fatemi, A. H., Fadafen , G. H. K. (2013). Examining the relationship between willingness to communicate in English, communication confidence and classroom environment. International Journal of Research Studies in Educational Technology , 3(11), 23-40. Hashimoto, Y. (2002). Motivation and willingness to communicate as predictors of reported L2 use: The Japanese ESL context. Second Language Studies, 20(2), 29-70. Hiromori, T. (2006). The effects of educational intervention on L2 learners’ motivational development. JACET Bulletin, 43, 1-14. MacIntyre, P. D. (1994). Variables underlying willingness to communicate: A causal analysis. Communication Research Reports, 11, 135–142. MacIntyre, P. D. (2007). Willingness to communicate in the second language: Understanding the decision to speak as a volitional process. Modern Language Journal, 91, 564-576. MacIntyre, P. D. (2012). Currents and waves: Examining willingness to communicate on multiple timescales. Contact: Research symposium special issue, 38(2), 12-22. MacIntyre, P. D., & Charos, C. (1996). Personality, attitudes, and affect as predictors of second language communication. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 15, 3-26. MacIntyre, P. D., Clement, R., Dörnyei, Z., & Noels, K. (1998). Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in a L2: A situational model of L2 confidence and affiliation. Modern Language Journal, 82, 545–562. Markus, H., & Nurius, P. (1986). Possible selves. American Psychologist, 41, 954–969. Matsuoka, R. (2005). Willingness to communicate among Japanese college students. In Proceedings of the 10th Conference of Pan-Pacific Association of Applied Linguistics (pp. 165-176). Retrieved April 12, 2011 from http://www.paaljapan.org/resources/proceedings/PAAL10/pdfs/matsuoka.pdf McCroskey, J. C. (1992) Reliability and validity of the willingness to communicate scale. Communication Quarterly, 40, 16-25. McCroskey, J. C., & Baer, J. E. (1985, November). Willingness to communicate: The construct and its measurement. Paper presented at the annual convention of the Speech Communication Association, Denver, CO. McCroskey, J. C., & V. P. Richmond (1987). Willingness to communicate. In J. C. McCroskey amd J. A. Daly (Eds.), Personality and interpersonal communication (pp. 129-156). Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications. McCroskey, J. C., & V. P. Richmond (1991). Willingness to communicate: A cognitive view. In M. Both-Butterfield (Ed.), Communication, cognition and anxiety (pp. 19-44). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Murayama, K., Elliot, A. J. & Friedman, R. (2012). Achievement goals. In R. M. Ryan, (ed.), The Oxford handbook of human motivation. Oxford library of psychology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 191-207. Murayama, K., Matsumoto, M., Izuma, K., & Matsumoto, K. (2010). Neural basis of the undermining effect of monetary reward on intrinsic motivation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107(49), 20911-20916. Murayama, K., Matsumoto, M., Izuma, K, Sugiura, A., Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L., & Matsumoto, K. (2014). How self-determined choice facilitates performance: A key role of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Murphey, T. (2011, February). Inviting student voice. Paper presented at MASH JALT Representables 2011: A weekend with Tim Murphey held at Seisen Jogakuin College, Nagano, Japan, February 11-12. Nakahira, S., Yashima, T., & Maekawa, Y. (2010). Relationships among motivation, psychological needs, FL WTC, and Can-Do statements of English language learning based on self-determination theory: preliminary study of non-English-major junior college students in Japan. JACET Kansai Journal, 12, 44-55. Noels, K. A., Clément, R., & Pelletier, L. G. (1999). Perceptions of teacher communicative style and students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Modern Language Journal, 83, 23–34. Noels, K. A., Clément, R., & Pelletier, L. G. (2001). Intrinsic, extrinsic, and integrative orientations of French Canadian learners of English. Canadian Modern Language Review, 57, 424-442. Noels, K. A., Pelletier, L. G., Clément, R., & Vallerand, R. J. (2003). Why are you learning a second language? Motivational 11 orientations and self-determination theory. Language Learning, 53, 53-64. AUTHOR. (2012). Do Japanese JHS students have Ideal L2 Selves? Evidence from research in progress on the influence of multimedia use on affective variables. In A. Stewart & N. Sonda (Eds.), JALT2011 Conference Proceedings, (pp. 168-178). Tokyo: JALT. AUTHOR. (2013, June). Apples & Hippos: The positive results of a video intervention on student confidence and WTC. Paper presented at JALT CALL 2013, Matsumoto, Japan, May 31- June 2. AUTHOR. (2014, February). The positive results of an iPad video intervention on JHS student Ideal L2 Selves, confidence, anxiety, and WTC. Paper presented at the Kanda University of International Studies (KUIS) and the Apple Distinguished Educators (ADE) conference Paperless: Innovation and technology in education. Tokyo, Japan, February 1. AUTHOR. (2014a). The influence of technology in the classroom: An analysis of an iPad and video intervention on JHS students’ confidence, anxiety, and FL WTC. The JALT CALL Journal, 10(1), 49-68. AUTHOR. (2014b). Japanese JHS students' Ideal L2 Selves: Confidence, anxiety, and willingness to communicate. The Language Teacher, 38(6), 11-18. AUTHOR. (in press). An iPad intervention: Japanese JHS students’ amotivation, motives, and Ideal L2 Selves. Manuscript under review. Language Education in Asia. Pintrich, P. R., & Schunk, D. H. (2002). Motivation in Education: Theory, Research and Applications (2nd Ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall. Przybylski, A. K., Rigby C. S., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). A motivational model of video game engagement. Review of General Psychology, 14, 154-166. doi:10.1037/a0019440 Przybylski, A. K., Weinstein, N., Murayama, K., Lynch, M. F., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). The ideal self at play: The appeal of video games that let you be all you can be. Psychological Science, 23, 69-76. doi:10.1177/0956797611418676 Rawson, T. W. (2008). Video news casting in English: Using video to promote English communications. The Language Teacher, 32(4), 15-16. Richards, J. C. (2012). Some affective variables in language teaching. The Language Teacher, 36(6), 49-50. Rosenthal, R., & Rosnow, R. L. (1991). Essentials of behavioral research: Methods and data analysis. Boston, MA: McGraw Hill. Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54-67. Ryan, R. M., Rigby, C. S., & Przybylski, A. K. (2006). Motivational pull of video games: A self-determination theory approach. Motivation and Emotion, 30, 347-365. Shrosbee, M. (2008). Digital video in the language classroom. The JALT CALL Journal, 4(1), 74-84. Takiguchi, H. (2002). Real-time communication class with foreign countries using a video conferencing telephone system. STEP Bulletin, 14, 142-155. Ushioda, E. (2006). Language motivation in a reconfigured Europe: access, identity, autonomy. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 27(2), 148-161. Watanabe, M. (2013). Willingness to communicate and Japanese high school English learners. JALT Journal, 35(2), 153-172. Woodrow, L. (2006). Anxiety and speaking English as a second language. RELC Journal, 37(3), 308-328. DOI: 10.1177/0033688206071315 Yashima, T. (2000). Orientations and motivation in foreign language learning: A study of Japanese college students. JACET Bulletin, 31, 121–133. Yashima, T. (2002). Willingness to communicate in a second language: The Japanese EFL context. Modern Language Journal, 86, 55–66. Yashima, T., Noels, K., Shizuka, T., Takeuchi, O., Yamane, S., & Yoshizawa, K. (2009). The interplay of classroom anxiety, intrinsic motivation, and gender in the Japanese EFL context. Journal of Foreign Language Education and Research , 17, 41-64. Yashima, T., Zenuk-Nishide, L., & Shimizu, K. (2004). The influence of attitudes and affect on willingness to communicate and second language communication. Language Learning, 54, 119-152. 12 Appendix A The SDT Instrument Sub-scale Cronbach’s alpha and Items’ Mean and SD (N = 140; = 0.89) Amotivation ( = .75) I don't know why I must study English. Plainly speaking, I'd rather do anything other than study English. Honestly, I don't know, I truly have the impression of wasting my time in studying English. As for studying English, I cannot come to see why I study English. External Regulation ( = .68) As for studying English, I do so in order to get a more prestigious job later on. As for studying English, I do so because I have the impression that it is expected of me. As for studying English, I do so in order to have a better salary later on. Introjected Regulation ( = .69) Because I would feel ashamed if I couldn't speak to my friends from the English-speaking community in English. Because if I can speak English, I will be aware that I am an internationally-minded person. Because I would feel guilty if I didn't know English. Identified Regulation ( = .75) Because I want to be a person who can speak a foreign language. Because I think it is important for my personal development. Because I want to be a person who can speak English. Intrinsic Motivation (Knowledge) ( = .81) For the pleasure that I experience in knowing more about English literature. For the satisfied feeling I get in finding out new things. Because I enjoy the feeling of acquiring knowledge about the English-speaking community and their way of life. Intrinsic Motivation (Accomplishment) ( = .81) For the pleasure I experience when surpassing myself in my English studies. For the enjoyment I experience when I grasp a difficult construct in English. For the satisfaction I feel when I am in the process of accomplishing difficult exercises in English. Intrinsic Motivation (Stimulation) ( = .83) For the "high" I feel when hearing foreign languages spoken. For the "high" that I experience while speaking English. For the pleasure I get from hearing English spoken by native speakers. 13 Mean (SD) 2.76 (1.42) 2.30 (1.23) 2.18 (1.27) 2.36 (1.15) 2.76 (1.41) 2.77 (1.28) 3.00 (1.27) 2.96 (1.35) 2.58 (1.16) 4.09 (1.48) 3.45 (1.32) 3.91 (1.51) 2.97 (1.20) 3.23 (1.35) 3.11 (1.29) 3.08 (1.18) 2.98 (1.23) 2.90 (1.25) 2.95 (1.30) 2.87 (1.35) 2.80 (1.34) Appendix B The WTC Instrument Scales’ Cronbach’s alpha, and Items’ Mean and SD (N = 120) Sub-section affective variable tested (Whole sub-section Cronbach’s alpha) 1) Asking a Japanese teacher for a copy of an audio recording. Complaining to a Japanese teacher that the speed of the listening test was too quick to 2) catch. Complaining to a native teacher that the speed of the listening test was too quick to 3) catch. 4) Giving a reply for an American television program covering student life in Japan. Making a telephone call in order to make a reservation at a hotel in English speaking 5) country. 6) Interviewing a native English speaker for an article in the school paper. 7) Asking a pair work partner for the time now. 8) Speaking to a foreigner sitting next to you on the train. 9) Asking a native English speaking teacher the meaning of a word. 10) Making a phone call to invite a friend who can speak only English to a party. 11) Asking a native teacher for a handout given when you were absent from class. 12) Talking to your pair work partner about a TV program which you watched. 13) Stand in front of the entire class and talk about a TV program which you watched. 14) Helping a foreigner that looks troubled because he cannot read a restaurant menu. 15) Asking a foreigner for the time when you do not know it. Help a troubled foreigner because he cannot understand what the salesclerk says at the 16) supermarket. Greet a group of medical professionals who came from the United States to visit your 17) school. In front of your class, answer a native teacher's questions about your trip during summer 18) vacation. Stand in front of your class and talk about your memories of your summer vacation for 19) two minutes. To buy a rare CD sold only overseas, call a CD store in the United States by telephone to 20) order one. 21) Take a small number of English speaking people sightseeing in Tokyo for one day. 22) Call your host family and thank them for letting you stay with them. 23) Tell your pair-work partner in English the way to a place using a map. 24) Say five English words which start with S to your pair work partner. 25) Ask a native English speaking teacher to copy a CD. 26) Ask the meaning of a word to a Japanese teacher using classroom English. 27) Stand and tell your entire class five words using classroom English. Talk to your pair-work partner about your memories of summer vacation for two 28) minutes. 29) Help a foreigner who looks troubled at the station. Participate in an English language speech contest for Japanese students. Judges are 30) native speakers. Confidence* Anxiety** WTC* (0.94) (0.96) (0.93) 3.24 (1.36) 2.93 (1.39) 2.96 (1.29) 2.85 (1.67) 3.18 (1.58) 2.58 (1.49) 2.36 (1.36) 3.68 (1.67) 2.17 (1.16) 2.31 (1.37) 4.57 (1.59) 2.38 (1.64) 2.34 (1.36) 4.21 (1.58) 2.17 (1.22) 3.17 (1.36) 3.85 (1.70) 2.16 (1.52) 3.55 (1.47) 2.44 (1.40) 3.05 (1.45) 3.09 (1.66) 2.24 (1.33) 2.66 (1.45) 3.06 (1.60) 2.00 (1.40) 4.78 (1.61) 1.77 (1.33) 2.34 (1.37) 4.19 (1.63) 2.08 (1.26) 2.21 (1.28) 4.27 (1.71) 1.94 (1.15) 2.39 (1.40) 4.19 (1.67) 2.21 (1.30) 1.96 (1.34) 2.55 (1.36) 2.59 (1.45) 3.80 (1.68) 2.64 (1.37) 2.91 (1.35) 2.61 (1.49) 4.48 (1.65) 4.09 (1.51) 3.63 (1.53) 2.66 (1.52) 3.54 (1.58) 3.21 (1.49) 3.81 (1.67) 1.98 (1.38) 2.54 (1.39) 2.45 (1.28) 3.23 (1.54) 2.38 (1.13) 2.61 (1.15) 2.11 (1.25) 2.49 (1.40) 3.60 (1.68) 2.21 (1.32) 2.43 (1.35) 4.25 (1.61) 2.24 (1.34) 1.80 (1.24) 4.64 (1.81) 1.64 (1.16) Additional questions on confidence, anxiety, and WTC Were you video-recorded (with a camcorder or iPad) during English class? If yes, please circle from 1 (no influence) to 6 (a lot of influence) for the three questions below. 14 2.71 (1.34) 3.17 (1.44) 2.09 (1.36) 3.08 (1.34) 2.34 (1.27) 2.70 (1.17) 2.68 (1.43) 1.99 (1.31) 2.54 (1.39) 2.76 (1.36) 2.61 (1.35) 3.96 (1.49) 2.58 (1.38) Appendix C a) Do you feel being video recorded increased your confidence to speak in English? b) Do you feel being video recorded increased your desire to speak in English? c) Do you feel being video recorded reduced your nervousness to speak in English? 3.62 (1.44) 2.68 (1.43) 4.24 (1.67) 3.17 (1.44) 3.69 (1.66) 3.16 (1.52) 3.07 (1.55) 4.19 (1.73) 4.06 (1.58) 3.62 (1.57)