PowerPoint

advertisement

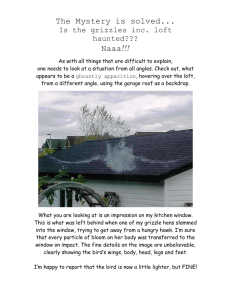

CAS LX 502 Semantics 2b. Sense and concepts 2.4- Mental representations • We can talk about things that don’t exist, things as they might have been, things as they will be. Language is not limited to references to tangible entities and properties in the real world. • We have a mental representation of the meaning of language (and much of what we are studying here are the properties of these mental representations). *Images • The mental representation of the meaning of a word, even a name, cannot simply be an image or other perceptually grounded representation (justice? happiness?). Rather, we have a complex mental concept as the meanings of words—their sense. • Perceptual representations may be part of the concept, but they are not the all there is to the concept. Concepts transcend words • Of course, there need not be a word for there to be a concept. Concepts can be described, and given a designation if they are useful. sniglet: n. Any word that doesn’t appear in the dictionary but should. • Rich Hall had a series of books in the 80’s containing these. eastroturf: n. The artificial grass in Easter baskets. furnidents: n. The indentations that appear in carpets after a piece of furniture has been removed. What is our concept of bird? • When we think of the meaning of bird, the concept of bird, we think of it as applying to some things and not others. At a first pass, it might have to satisfy these necessary conditions (linking this concept to other concepts: animal, wings, …) • • • • • It is an animal It has two wings It can fly It sings or chirps … Necessary and sufficient • Not all of these linked concepts are really necessary for something to fall under the concept bird. • Is a penguin a bird? Surely. Yet it doesn’t fly. Is a fish with three eyes really a fish? So what are the sufficient conditions? According to Webster • Bird: n. 2 : any of a class (Aves) of warm-blooded vertebrates distinguished by having the body more or less completely covered with feathers and the forelimbs modified as wings. • Wing: n. 1 a : one of the movable feathered or membranous paired appendages by means of which a bird, bat, or insect is able to fly; also : such an appendage even though rudimentary if possessed by an animal belonging to a group characterized by the power of flight According to Webster • Bird: n. 2 : any of a class (Aves) of warm-blooded vertebrates distinguished by having the body more In other or less completely covered with feathers and the words, we ask forelimbs modified as wings. a bird expert. • Wing: n. 1 a : one of the movable feathered or membranous paired appendages by means of which a bird, bat, or insect is able to fly; also : such an appendage even though rudimentary if possessed by an animal belonging to a group characterized by the power of flight Thus: penguins are birds? Folk semantics • Yet, we’re pretty happy to call penguins birds, as well as ostriches. We might call a whale or a dolphin a fish, or we might call a tomato a vegetable, even if the experts would tell us otherwise. We may be able to discern the difference between an elm and a beech only by seeing how an expert reacts when faced with one. • We have some kind of concept of fish, vegetable, bird, elm that doesn’t seem to rely on a strict definition (necessary and sufficient conditions). Prototypes • So how is our conceptual knowledge organized? Perhaps a concept has a prototypical member, meeting all of the conditions, where things that meet only some of the conditions (having only some of the characteristic features) are more peripheral. The closer the match, the more typical. • Some features are clearly more fundamental than others. A mechanical bird would seem a much less typical bird than an ostrich—probably not even a bird at all. Characteristic features, prototypical exemplars • In a sense, these ideas make intuitive sense—but in another sense, they are no use to us. These don’t seem to tell us anything about how concepts can and can’t be organized, really. They don’t explain why concepts are the way they are. They just give us a language of description once we already know the facts. The acquisition of concepts • Any attempt to define a concept will quite rapidly run into a circularity problem. Concepts are clearly related to one another. • Cf. conceptual networks: A duck is a bird, and inherits from bird the conceptual associations bird has, such as being an animal, inheriting the conceptual associations animal has, etc.). • But eventually, there must be nothing to reduce to. (Or is it turtles all the way down?) The acquisition of concepts • This is a problem for the philosophers, perhaps, but it does not seem beyond the realm of possibility that there are a certain number of fundamental concepts that we start out with (perhaps like the structure of language attributable to UG), and from which other concepts are derived. The philosophical implications are many. But we do seem, as kids, to know how to characterize doggie when a doggie is pointed out to us (cf. Quine’s gavagai). Language, thought, and reality • “Don’t you see that the whole aim of Newspeak is to narrow the range of thought? In the end we shall make thoughtcrime literally impossible, because there will be no words in which to express it. Every concept that can ever be needed, will be expressed by exactly one word, with its meaning rigidly defined and all its subsidiary meanings rubbed out and forgotten.” (according to Syme, from George Orwell’s 1984, of course) Sapir-Whorf • B.L. Whorf, studying Uto-Aztecan languages, observed that agreement systems, declensions, tense-marking vary widely across languages, and languages often divide word into classes based on rather arbitrary criteria. • He has since been much maligned for suggesting that these classifications impose a restriction on how speakers classify concepts—taken to an extreme, this leads to the idea of Newspeak. Known as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. Pinker v. Whorf • Pinker (The Language Instinct) runs through a number of arguments against the idea that language determines concepts. • 5-mo olds: react to unexpected changes in cardinality. • Vervet monkey’s sister: bit VM’s antagonist’s sister. • Mental rotation: 56 RPM. • So what is the language of concepts? Not English. We might call it Mentalese, if we so wish, but whatever we call it, it is richer, more unambiguous, and certainly distinct from spoken languages. snow powder flurry sleet hail blizzard dusting hardpack slush avalanche