幻灯片 1 - suda.edu.cn

advertisement

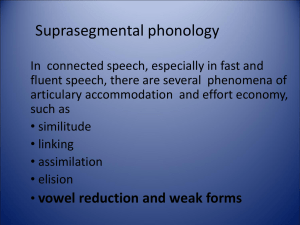

Group 2,Class 1 Structure Introduction--AmE & BrE Background--historical reason Differences -- grammar pronunciation spelling writing Conclusion Written forms of American and British English as found in newspapers and textbooks vary little in their essential features, with only occasional noticeable differences in comparable media. This kind of formal English, particularly written English, is often called 'standard English '. However, there are still many remarkable differences between the two languages. Since it is of vital importance for us English majors to distinct the two different branches of English, our group focus on two questions: What is the historical reason for American English is different from British English? What is the difference between them? Here, we regard Received Pronunciation (RP) as British English (BrE) and General American (GAm) as American English (AmE). Nouns In BrE, collective nouns can take either singular (formal agreement) or plural (notional agreement) verb forms, according to whether the emphasis is, respectively, on the body as a whole or on the individual members. For example: A committee was appointed . The committee were unable to agree. In AmE, collective nouns are usually singular in construction: the committee was unable to agree. AmE, however, may use plural pronouns in agreement with collective nouns: the team take their seats, rather than the team takes its seats. The rule of thumb is that a group acting as a unit is considered singular and a group of "individuals acting separately" is considered plural. Nouns The difference occurs for all nouns of multitude. For instance, BrE: The Clash are a well-known band; AmE: The Clash is a well-known band. BrE: Spain are the champions; AmE: Spain is the champion. Proper nouns that are plural in form take a plural verb in both AmE and BrE For example, The Beatles are a well-known band; The Saints are the champions. Use of tenses Traditionally, BrE uses the present perfect tense to talk about an event in the recent past and with the words already, just, and yet. In American usage, these meanings can be expressed with the present perfect (to express a fact) or the simple past (to imply an expectation). Recently, the American use of just with simple past has made inroads into BrE, most visibly in advertising slogans and headlines such as "Cable broadband just got faster". "I've just arrived home." / "I just arrived home." "I've already eaten." / "I already ate." Use of tenses Similarly, AmE occasionally replaces the past perfect tense with the simple past. In BrE, have got or have can be used for possession and have got to and have to can be used for the modal of necessity. The forms that include ‘‘got’’ are usually used in informal contexts and the forms without got in contexts that are more formal. In American speech the form without got is used more than in the UK, although the form with got is often used for emphasis. Colloquial AmE informally uses got as a verb for these meanings – for example, I got two cars, I got to go. Prepositions and adverbs (1) In the United States, the word through can mean "up to and including" as in Monday through Friday. In the UK Monday to Friday, or Monday to Friday inclusive is used instead; Monday through to Friday is also sometimes used. British sportsmen play in a team; American athletes play on a team. (Both may play for a particular team.) Prepositions and adverbs (2) In AmE, one always speaks of the street on which an address is located, whereas in BrE in can also be used in some contexts. In suggests an address on a city street, so a service station (or a tourist attraction or indeed a village) would always be on a major road, but a department store might be in Oxford Street. Moreover, if a particular place on the street is specified then the preposition used is whichever is idiomatic to the place, thus "at the end of Churchill Road." Prepositions and adverbs (3) BrE favours the preposition at with weekend ("at (the) weekend(s)"); the constructions on, over, and during (the) weekend(s) are found in both varieties but are all more common in AmE than BrE. Adding at to the end of a question requesting a location is common in AmE, for example, "where are you at?", but would be considered superfluous in BrE. However, some southwestern British dialects use to in the same context; for example "where are you to?” to mean "where are you". Differences in pronunciation between American English (AmE) and British English (BrE) can be divided into: 1)differences in accent. 2)differences in the pronunciation of individual words in the lexicon. BrE AmE words /æ/ /ɑ/ annato, BangladeshA2, Caracas, chiantiA2, Galapagos, GdańskA2, grappaA2, gulagA2, HanoiA2, JanA2 (male name, e.g. Jan Palach), KantA2, kebab, Las (placenames, e.g. Las Vegas), Mafia, mishmashA2, MombasaA2, Natasha, Nissan, Pablo, pasta, PicassoA2, ralentando, SanA2 (names outside USA; e.g. San Juan), SlovakA2, Sri LankaA2, Vivaldi, wigwamA2, YasserA2 (and A in many other foreign names and loanwords) /iː/ /ɛ/ aesthete, anaesthetize, breveA2, catenaryA2, Daedalus, devolutionA2,B2, ecumenicalB2, epochA2, evolutionA2,B2, febrileA2, Hephaestus, KenyaB2, leverA2, methane, OedipusA2, (o)estrus, penalizeA2, predecessorA2, pyrethrinA2, senileA2, hygienic /ɒ/ /oʊ/ Aeroflot, compost, homosexualB2, Interpol, Lod, pogrom, polkaB2, produce (noun), Rosh Hashanah, sconeA2,B2, shone, sojourn, trollB2, yoghurt /ɑː/ /æ/ (Excluding trap-bath split words) banana, javaA2, khakiA2, morale, NevadaA2, scenarioA2, sopranoA2, tiaraA2, Pakistani /ɛ/ /i/ CecilA2,B2, crematoriumA2, cretin, depot, inherentA2,B2, leisureA2, medievalA2, reconnoitreA2, zebraB2, zenithA2,B2 /æ/ /eɪ/ compatriot, patriotB2, patronise, phalanx, plait, repatriate, Sabine, satrapA2, satyrA2, basilA2 (plant) /ɪ/ /aɪ/ dynasty, housewifery, idyll, livelongA2, long-livedA2, privacyB2, simultaneous, vitamin. Also the suffix -ization. See also -ine. /z/ /s/ AussieA2, blouse, complaisantA2, crescent, diagnoseA2, erase, GlasgowA2, parse, valise, trans-A2,B2 (in some words) /ɑː/ /eɪ/ amenA2, charadeB2, cicada, galaA2, promenadeA2, pro rata, tomato, stratum /əʊ/ /ɒ/ codify, goffer, ogleA2, phonetician, processor, progress (noun), slothA2,B2, wont A2, wroth /ʌ/ /ɒ/ accomplice, accomplish, colanderB2, constableB2, Lombardy, monetaryA2, -mongerA2 /ɒ/ /ʌ/ hovelA2,B2, hover. Also the strong forms of these function words: anybodyA2 (likewise every-, some-, and no-), becauseA2,B2 (and clipping 'cos/'cause), ofA2, fromA2, wasA2, whatA2 (sou (sile nde nt) d) chthonic, herbA2 (plant), KnossosB2, phthisicB2, salve, solder /ɑː/ /ɚ/ Berkeley, Berkshire, clerk, Derby, Hertford. (The only AmE word with <er> = [ɑr] is sergeant). /aɪ/ /i/ eitherA2,B2, neitherA2,B2, Pleiades. See also -ine. /iː/ /aɪ/ albino, migraineB2. Also the prefixes anti-A2, multi-A2, semi-A2 in loose compounds (e.g. in anti-establishment, but not in antibody). See also -ine. /ə/ /ɒ/ hexagon, octagon, paragon, pentagon, phenomenon. /iː/ /eɪ/ eta, beta, quayA2, theta, zeta /aɪ/ /ɪ/ butylB2, diverge, minorityA2,B2, primer (schoolbook). See also -ine. /ə/ /ɒ/ hexagon, octagon, paragon, pentagon, phenomenon. /iː/ /eɪ/ eta, beta, quayA2, theta, zeta /aɪ/ /ɪ/ butylB2, diverge, minorityA2,B2, primer (schoolbook). See also -ine. /ɛ/ /eɪ/ ateB2 ("et" is nonstandard in America), mêlée, chaise longue /ɜːz/ /us/ Betelgeuse, chanteuse, chartreuseA2, masseuse /eɪ/ /æ/ apricotA2, dahlia, digitalis, patentA2,B2, comrade (silent) (sounded) medicineB2. See also -ary -ery -ory -bury, -berry /ɒ/ /ə/ Amos, condom, Enoch /ʃ/ /ʒ/ AsiaB2, PersiaB2, versionB2 /ə/ /oʊ/ borough, thorough (see also -ory and -mony) /ɪr/ /ɚ/ chirrupA2, stirrupA2, sirupA2, squirrel /siː/ /ʃ/ cassia, CassiusA2, hessian /tiː/ /ʃ/ consortium /uː/ /ju/ couponA2, fuchsine, HoustonB2 /uː/ /ʊ/ boulevard, snooker, woofA2 (weaving) /ɜː(r)/ /ʊr/ connoisseurA2, entrepreneurA2 /ɜː/ /oʊ/ föhnB2, MöbiusB2 /ə/ /eɪ/ DraconianA2, hurricaneB2 /eɪ/ /i/ deityA2,B2, Helene /juː/ /w/ jaguar, Nicaragua /ɔː/ /ɑ/ launch, saltB2 /ɔː(r)/ /ɚ/ record (noun), stridorA2,B2 /ziː/ /ʒ/ Frasier, Parisian, Malaysia /æ/ /ɒ/ twatB2 /ɒ/ /æ/ wrath /ɑː/ /ət/ nougat /ɑː/ /ɔ/ Utah /ɑː/ /ɔr/ quarkA2,B2 /æ/ /ɛ/ femme fataleA2 /aɪ/ /eɪ/ Isaiah /aʊ/ /u/ nousA2 /ɒ/ /ə/ Amos, condom, Enoch /ð/ /θ/ booth /ʃ/ /ʒ/ AsiaB2, PersiaB2, versionB2 /diː/ /dʒi/ cordiality /ə/ /oʊ/ /dʒ/ /ɡdʒ/ suggestA2 borough, thorough (see also ory and -mony) /eɪ/ /ə/ template /ɪr/ /ɚ/ /eɪ/ /ət/ tourniquet chirrupA2, stirrupA2, sirupA2, squirrel /ə(r)/ /ɑr/ MadagascarA2 /siː/ /ʃ/ cassia, CassiusA2, hessian /ə(r)/ /jɚ/ figureA2 for the verb /tiː/ /ʃ/ consortium /ə/ /ɛ/ nonsense /uː/ /ju/ /ɛ/ /ɑ/ envelopeA2,B2 couponA2, fuchsine, HoustonB2 /ɛ/ /ə/ Kentucky /uː/ /ʊ/ /ə/ /æ/ trapeze boulevard, snooker, woofA2 (weaving) (silen (soun medicineB2. See also -ary -ery t) de -ory -bury, -berry d) /ɜː(r)/ /ʊr/ connoisseurA2, entrepreneurA2 /ɜː/ /oʊ/ föhnB2, MöbiusB2 /ə/ /eɪ/ DraconianA2, hurricaneB2 /eɪ/ /i/ deityA2,B2, Helene /juː/ /w/ jaguar, Nicaragua /ɔː/ /ɑ/ launch, saltB2 /ɔː(r)/ /ɚ/ record (noun), stridorA2,B2 /ziː/ /ʒ/ Frasier, Parisian, Malaysia /æ/ /ɒ/ twatB2 /ɒ/ /æ/ wrath /ɑː/ /ət/ nougat /ɑː/ /ɔ/ Utah /ɑː/ /ɔr/ quarkA2,B2 /æ/ /ɛ/ femme fataleA2 /aɪ/ /eɪ/ Isaiah /aʊ/ /u/ nousA2 /a:/--/æ/ glass /iәr/--/i:r/ hero /o/--/Λ/ shop /o/--/o:/ dog /uәr/-/ur/ curious / Λr/--/ә:r/ hurry /ju:/--/u:/supermarket /æ/--/e/ ration /ai/--/i/ fragile Spelling BrE IPA AmE IPA Notes barrage ˈbær.ɑːʒ (1) bəˈrɑʒ The AmE pronunciations are for distinct senses (1) "sustained weapon-fire" vs (2) "dam, barrier" (Compare garage below.) (2) ˈbær.ɪdʒ garage (1) ˈɡærɪdʒ ɡəˈrɑ(d)ʒ (2) ˈɡærɑːʒ vase vɑːz (1) veɪs The AmE reflects French stress difference. The two BrE pronunciations may represent distinct meanings for some speakers; for example, "a subterranean garage for a car" (1) vs "a petrol garage" (2). (Compare barrage above.) The BrE pronunciation also occurs in AmE (2) veɪz z (the zɛd letter) ziː The spelling of this letter as a word corresponds to the pronunciation: thus Commonwealth (including, usually, Canada) zed and U.S. (and, occasionally, Canada) zee. Stress For many loanwords from French where AmE has final-syllable stress, BrE stresses an earlier syllable. Such words include: BrE first-syllable stress: adult, ballet; A few French words have other stress differences: AmE first-syllable, BrE last-syllable: address, cigarette AmE first-syllable, BrE second-syllable: liaison AmE second-syllable, BrE last-syllable: New Orleans BrE dialogue archaeology colour favourite jewellry programme storey AmE dialog archeology color favorite jewelry program story BrE centre theatre metre AmE center theater meter BrE licence practise analyse globalisation AmE license practice analyze globalization BrE grey manoeuvre AmE gray maneuver Use of capitalization varies. Sometimes, the words in titles of publications, newspaper headlines, as well as chapter and section headings are capitalized in the same manner as in normal sentences. That is, only the first letter of the first word is capitalized, along with proper nouns, etc. Many British tabloid newspapers (such as The Sun, The Daily Sport, News of the World) use fully capitalized headlines for impact, as opposed to readability (for example, BERLIN WALL FALLS or BIRD FLU PANIC). On the other hand, the broadsheets (such as The Guardian, The Times, and The Independent) usually follow the sentence style of having only the first letter of the first word capitalized. However, publishers sometimes require additional words in titles and headlines to have the initial capital, for added emphasis, as it is often perceived as appearing more professional. In AmE, this is common in titles, but less so in newspaper headlines. The exact rules differ between publishers and are often ambiguous; a typical approach is to capitalize all words other than short articles, prepositions, and conjunctions. This should probably be regarded as a common stylistic difference, rather than a linguistic difference, as neither form would be considered incorrect or unusual in either the UK or the US. After our research, we have already known the main differences between AmE and BrE in grammar, pronunciation, spelling and writing briefly, and have had a general idea of why American English is different from British English in terms of history. We hope that our presentation is helpful for you with your English study. 1,New Concept English 2,Algeo, John (2006). British or American English?. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 3,Hargraves, Orin (2003). Mighty Fine Words and Smashing Expressions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 4,McArthur, Tom (2002). The Oxford Guide to World English. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 5,Peters, Pam (2004). The Cambridge Guide to English Usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 6,Trudgill, Peter and Jean Hannah. (2002). International English: A Guide to the Varieties of Standard English.

!["The [AME program] has proved to be invaluable in](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/009071930_1-d58255f43c2ddfa1ebafddfbf4735dbd-300x300.png)