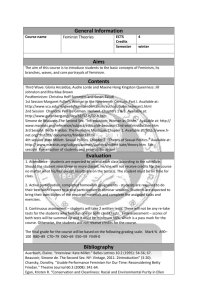

Roads to Utopia Barnita Bagchi

advertisement

Roads to Utopia Barnita Bagchi Herland (1915) Charlotte Perkins Gilman Charlotte Perkins Gilman 1860-1935 Born in Connecticut, into a liberal milieu. Her father’s aunt was Herriet Beecher Stowe. Her father abandoned the family. Forced to move from relative to relative. Studied at Rhode Island School of Design (1878-80). Earned her living designing greetings cards. Charlotte Perkins Gilman • Married CW Stetson, an artist. • Suffered from depression after the birth of their daughter. • Her doctor, horrifically, recommended she "live as domestic a life as possible" and "never touch a pen, brush or pencil as long as you live". • This was used satirically by CPG in her famous short story, 'The Yellow Wallpaper', which first appeared in New England Magazine in January 1892. The Yellow Wallpaper • A woman ordered total rest, slowly going mad. • Sees a woman in the pattern of the yellow wallpaper of the room where is incarcerated. • Thinks the woman wants to get out. • About the horrors of women’s creativity being stifled in the name of medical treatment of depression, among other matters. Herland • Offers a portrait of a contrasting world where women (and men, eventually) are supposed to live in a healthy, happy, creative, free way. • Written by a woman who lived experimentally, trying to embody utopia in real life. • As a journalist, Gilman edited The Forerunner, a very utopian title for a journal. • She divorced, moved to California, and was inspired by Nationalism, a movement inspired by the utopian socialism of Edward Bellamy, the same man whose Looking Backward Morris had criticized. Women and Economics • Published in 1898. • Attacks gendered social roles. Men are not necessarily aggressive, women are not necessarily maternal. • Advocated professional independence for women—helps both men and women to lead more enriched lives, according to this. Herland • About a highly evolved and civilized female society. • Years of evolution have succeeded in empowering women with the power to reproduce by themselves. • Three men enter the all-female utopia, and tell us about it. • Van (narrator) Terry, and Jeff • Three very different kinds of men. Herland • Fresh, direct opening: • This is written from memory, unfortunately. If I could have brought with me the material I so carefully prepared, this would be a very different story. Whole books full of notes, carefully copied records, firsthand descriptions, and the pictures—that's the worst loss. We had some bird's-eyes of the cities and parks; a lot of lovely views of streets, of buildings, outside and in, and some of those gorgeous gardens, and, most important of all, of the women themselves. Herland • We realise rather quickly that this is a man speaking about women. • Three very different kinds of men. Terry was rich enough to do as he pleased. His great aim was exploration. He used to make all kinds of a row because there was nothing left to explore now, only patchwork and filling in, he said. He filled in well enough—he had a lot of talents—great on mechanics and electricity. Had all kinds of boats and motorcars, and was one of the best of our airmen. Jeff Margrave was born to be a poet, a botanist—or both—but his folks persuaded him to be a doctor instead. He was a good one, for his age, but his real interest was in what he loved to call "the wonders of science." As for me, sociology's my major. You have to back that up with a lot of other sciences, of course. I'm interested in them all. Herland • Crucial questions to ask about the text: how it plays with the heterosexual romance plot, • the nature and reinvention of the male gaze in the novel. Herland "Girls!" whispered Jeff, under his breath, as if they might fly if he spoke aloud. "Peaches!" added Terry, scarcely louder. "Peacherinos—apricotnectarines! Whew!" They were girls, of course, no boys could ever have shown that sparkling beauty, and yet none of us was certain at first. We saw short hair, hatless, loose, and shining; a suit of some light firm stuff, the closest of tunics and kneebreeches, met by trim gaiters. As bright and smooth as parrots and as unaware of danger, they swung there before us, wholly at ease, staring as we stared, till first one, and then all of them burst into peals of delighted laughter. Then there was a torrent of soft talk tossed back and forth; no savage sing-song, but clear musical fluent speech. We met their laughter cordially, and doffed our hats to them, at which they laughed again, delightedly. Herland • By the time they get to the close of the novel, Van or Jeff no longer look on women as objects to be played with, adored, or demeaned. They see them as equals, while continuing to, indeeed, increasing in their appreciation of them. • A challenging literary task. Herland: Pre-History • • • • They were a polygamous people, and a slave-holding people, like all of their time; and during the generation or two of this struggle to defend their mountain home they built the fortresses, such as the one we were held in, and other of their oldest buildings, some still in use. Nothing but earthquakes could destroy such architecture—huge solid blocks, holding by their own weight. They must have had efficient workmen and enough of them in those days. They made a brave fight for their existence, but no nation can stand up against what the steamship companies call "an act of God." While the whole fighting force was doing its best to defend their mountain pathway, there occurred a volcanic outburst, with some local tremors, and the result was the complete filling up of the pass—their only outlet. Instead of a passage, a new ridge, sheer and high, stood between them and the sea; they were walled in, and beneath that wall lay their whole little army. Very few men were left alive, save the slaves; and these now seized their opportunity, rose in revolt, killed their remaining masters even to the youngest boy, killed the old women too, and the mothers, intending to take possession of the country with the remaining young women and girls. But this succession of misfortunes was too much for those infuriated virgins. There were many of them, and but few of these would-be masters, so the young women, instead of submitting, rose in sheer desperation and slew their brutal conquerors. This sounds like Titus Andronicus, I know, but that is their account. I suppose they were about crazy—can you blame them? Herland: Pre-History • Grisly, bloody genesis. Like Shakespeare’s raw revenge play, Titus Andronicus. • Slaves in revolt had to be killed by the women: no easy walk to utopia. • Racialized: white women. • Afterwards, women build a society with pain and hard work. • Motherhood that does not require men comes to them miraculously, and they cherish this. Herland: Motherhood • "I understand that you make Motherhood the highest social service—a sacrament, really; that it is only undertaken once, by the majority of the population; that those held unfit are not allowed even that; and that to be encouraged to bear more than one child is the very highest reward and honor in the power of the state." (Chapter 6) Herland: A Surprising Ideal We had expected a dull submissive monotony, and found a daring social inventiveness far beyond our own, and a mechanical and scientific development fully equal to ours. We had expected pettiness, and found a social consciousness besides which our nations looked like quarreling children -- feebleminded ones at that. We had expected jealousy, and found a broad sisterly affection, a fairminded intelligence, to which we could produce no parallel. We had expected hysteria, and found a standard of health and vigor, a calmness of temper, to which the habit of profanity, for instance, was impossible to explain -- we tried it. (Chapter 7) Herland: A Happy Education • Communal mothering. • a child in Herland is not any single mother’s possession. • Educating a child is the “highest art” • The children of Herland grow up “as naturally as young trees; learning through every sense; taught continuously but unconsciously -- never knowing they were being educated”. • Chapter 8 Herland: Woods, Gardens, and A Green World a land in a state of perfect cultivation, where even the forests looked as if they were cared for; a land that looked like an enormous park, only it was even more evidently an enormous garden. (Chapter 1) Herland: A Holland-like Land? • The country was about the size of Holland, some ten or twelve thousand square miles. One could lose a good many Hollands along the forest-smothered flanks of those mighty mountains. They had a population of about three million— not a large one, but quality is something. Fruits of the Forest, Care for Sustainable Ecology • Replanting forests with trees to get edible fruits and nuts. • These careful culturists had worked out a perfect scheme of refeeding the soil with all that came out of it. All the scraps and leavings of their food, plant waste from lumber work or textile industry, all the solid matter from the sewage, properly treated and combined—everything which came from the earth went back to it. The practical result was like that in any healthy forest; an increasingly valuable soil was being built, instead of the progressive impoverishment so often seen in the rest of the world. Chapter 7. Romances, Successful and Failed, and an Exit • Terry, Van and Jeff all experience romances with the women of Herland. Terry cannot cope with the new order, and regresses to sexual aggression: expelled. • Jeff’s partner is bearing a child: she stays in Herland. • Ellador, Van’s partner, and Van leave to visit the predictably dystopian Rest of the World. Matriarchal Imaginings, Female Utopia • Engels’ The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State (1884) posits, using contemporary anthropological work by Bachofen on the Mother-right, that the earliest societies were communistic, non-pairing or promiscuous, and matriarchal. • Historical evolution sees, in this narrative, movements towards private property, pairing families, and patriarchy, as all inter-related. • Aeschylus’ Greek play Eumenides: seen by many as dramatizing transition from mother-right to father-right. In the play, there is a debate about whether Orestes was right to kill his mother Clytemnestra, who had in turn killed her husband Agamemnon, for having sacrificed their daughter Iphigenia: a grisly chain. Athena, patroness of the Athenian city-state adjudicates that killing one’s mother is acceptable if the mother has in turn killed the father: the mother is merely the vessel who bears children, by this argument. The Furies, who want Orestes punished, belong to an earlier matriarchal order of deities. After this, many more imaginings of female and feminist utopia • Monique Wittig, Les Guerilleres (1964) • Joanna Russ, The Female Man (1975) • Marge Piercy, Woman on the Edge of Time (1976) • Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale (1986) Dystopic The questions raised • • • • Around production and gendered roles in it Around reproduction, mothering and fathering Around power, war, and peace Around the environment and the relationship between gendered roles, historical stages, and humanity’s relation to the nvironment • Around issues of power and powerlessness within language