MARIE-LOU IN ACTION “Recta manus”. The hand of the artist

advertisement

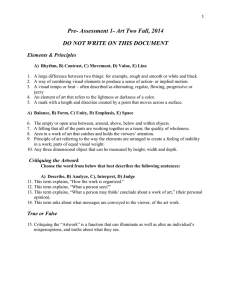

MARIE-LOU IN ACTION “Recta manus”. The hand of the artist. “Dexterous hand”: this two-word quote from the epitaph written by Angelo Poliziano in 1490 for the cenotaph of Giotto in Florence Duomo, has made a lasting impression in the history of art. During the Italian Mannerism period, it was used to designate the individual style of an artist. The creative ability was in those times synonymous with the craftsmanship of the creator, with its manual abilities. Since then, this notion has freed itself from the dominance of the formal and material artistic canon, and from its previous association with manual ability. As a result of this emancipation process, “recta manus” can now be seen as the “trace of artistic activity”, through which the thoughts of the performer come to existence. Today the artist is no longer only a craftsman, and accordingly, the material workmanship involved in creation is now more of an addition to the inner concept of the work of art, and no longer the entire work of art. An illustration of this change of meaning can be seen in abstract expressionism, including in its purest form: action painting. “Gesture-painting” in fact brings to mind Chinese and Japanese calligraphy, where the main point is the manual activity of the writer. This similarity is particularly significant in the works of artists such as Wols, Karl Otto Götz or Hans Hartung. But the most famous experimenter of all has to be Jackson Pollock: his painting was a theater. Through his works, the act of painting itself became a work of art. Painting in action is a performance. Considering the above, one may question the border between the performance and the painting, or even if this border really exists. What defines “Action Painting”? What builds its being? The evolution previously narrated suggests an answer to this question. The activity of the artist with his own hands is central in traditional painting. In fact, “painting” in its traditional sense refers only to the material result of artistic activity, but in fact the painting process is without bounds, it is infinite. The gesture of the artist must therefore be seen as having a ”social significance“. Gestures can in fact be considered as nonverbal communication. From the perspective of artistic tradition, iconic gestures are even more important, as they reflect the reality in its many forms, for example when they are portraying a concrete activity, allegorizing the outlines of objects or rearranging objects in space. Thus gestures do not only refer to concrete things, but must be seen, from a metaphorical perspective, as an alternate form of speech. As for the artistic activity itself, it should in turn be seen as symbolizing action. It is thus possible to interpret abstract expressionism, as a evocation of this symbolism through the movement of the artist’s hand. We have a good example of this phenomenon with Nicolas de Staël, who tried to blend abstraction with reality in many of his works. Those experiments have found their full expression and most obvious development in neoexpressionism, where the experience of the artistic gesture is connected with new forms of figuration. For example in the oeuvre of Basquiat one can find the modern- symbol repertoire of the colored metropolis, where graffiti signs, child drawings, comic figures, obscene wall-scribble, pictograms, advertisements, slogans, details of city maps , African masks and totem figures are mixed together. In fact, Basquiat can be seen as a precursor of “Bad Painting”. Marcia Tucker, curator of the 1978 exhibition of the New Museum of Contemporary Art, coined the term, and used it to designate works of such artists as HYPERLINK "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Wegman_%28photographer%29" \o "William Wegman (photographer)"William Wegman, HYPERLINK "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joan_Brown" \o "Joan Brown"Joan Brown, HYPERLINK "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Copley_%28artist%29" \o "William Copley (artist)"William N. Copley (CPLY) and HYPERLINK "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neil_Jenney" \o "Neil Jenney"Neil Jenney.As time progressed, “Bad Painting” became increasingly popular in Europe. For example we can recall the 2007 exhibition of the Vienna Museum of Modern Art (MUMOK) entitled : “Bad Painting – Good Art”. The art presented in this exhibit, including works by artists such as Georg Baselitz and Asger Jorn, was characterized by formal freedom and specific, naiveprimitive figuration (Arte Povera). As the next step in the spectrum of this evolution, we can find the art of Marie-Lou. Her work exemplifies both Action-Painting and Bad-Painting, with “recta manus” playing the central role. Her works also incorporate elements from all the artists mentioned above, as a flowing continuity of this creative movement. The binding of part-painted, part-costumed figures with the canvas, which is already present in her earlier creations, is more fully developed in the series “Painting-Surgeries”. Indeed, in the most recent pieces, the figures are changed radically by the use of paint itself, and their identities and backgrounds are rearranged and renewed in an artistic way. When seeing Marie-Lou’s entire oeuvre from the perspective of this historical progression, the art-historical genesis emerges clearly. The painted figure takes the role of the canvas and transforms itself,, through the action-painting process and the hand of the artist, in a “Bad-Painting”.