Chapter 5 – Causality (pp. 98-112) Overall teaching objective: To

advertisement

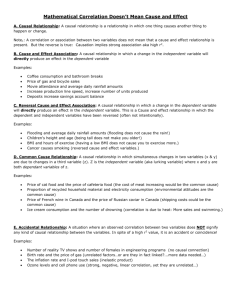

Chapter 5 – Causality (pp. 98-112) Overall teaching objective: To introduce undergraduate criminal justice research methods students to the rules researchers use to establish causal relationships. One of the toughest things to do in social research, maybe the toughest, is to prove a causal relationship between two variables. Over the years, social researchers have developed a set of rules for establishing causality or causal relationships between variables. Generally referred to as causal rules, these requirements constitute the standard for establishing whether a causal relationship exists between two variables. Each of these requirements must be met in order to confidently conclude that one variable (e.g. poverty) causes another (e.g. crime). Table 5.1 - Causal Rules (p. 99) Causal Rule Explanation Temporal order The cause (independent variable) must happen prior to the effect (dependent variable). In other words, the cause must happen first, then the effect. Correlation A change in the cause (independent variable) must result in a change in the effect (dependent variable). In other words, there must be a relationship between the two variables. Lack of plausible alternative explanations All other reasonable explanations (other independent variables) must be considered and eliminated. In other words, we have to rule out other potential causes. Making Research Real 5.1 – What Exactly is the Cause of Crime? (p. 98) Eddie, a police officer, is frustrated because “none of the theories he his learning about in graduate school totally explain all crime”. Eddie’s frustration is common among students. There is simply no single theoretical explanation (or cause) for all types of criminal behavior. Temporal Order (p. 99) The first causal rule, temporal order, requires that the cause must precede the effect. In other words, the variable that is alleged to be the cause of another variable must happen first. Making Research Real 5.2 – But it is Racial Profiling? (p. 100) Frustrated with a research finding that African-American drivers are stopped at disproportionately higher rates, a local advocate accuses the police department of racial profiling. A researcher argues that in order to confirm that a driver’s race is the reason for an officer’s stop one must prove that the officer knew the race of the driver prior to decision the stop. Making Research Real 5.3 – What (and When) do Officers Know? (p. 100) In an effort to determine whether police officers can accurately determine the race of a driver prior to the decision to stop. Alpert, Dunham and Smith (2007) conducted an observational study in Florida. They found that, overall, officers were only able to accurately perceive the race of the driver 29 percent of the time. This percentage was much lower in stops occurring at night. Correlation (p.101) The second causal rule, correlation, requires that the variables in a causal relationship be related to one another, or change together. A change in one variable must be associated with a change in another variable. Correlations can be positive or negative. Table 5.2 - Differences between types of correlations. (p. 103) Type of Correlation Definition Example Positive Correlations Increase in x → Increase in y When an increase in the independent variable (cause, or x) is associated with an increase in the dependent variable (effect, or y). An increase in illicit drug use (the independent variable) is associated with an increase in promiscuous sexual behaviors (the dependent variable). Decrease in x → Decrease in y When a decrease in the independent variable (cause, or x) is associated with a decrease in the dependent variable (effect, or y). A decrease in associations with other juvenile delinquents (the independent variable) is associated with a decrease in school related misbehavior (the dependent variable). When an increase in the An increase in alcohol Negative Correlations Increase in x → Decrease in y Decrease in x → Increase in y independent variable (cause, or x) is associated with a decrease in the dependent variable (effect, or y). consumption (the dependent variable) is associated with a decrease in academic performance (the dependent variable). When a decrease in the independent variable (cause, or x) is associated with an increase in the dependent variable (effect, or y). A decrease in school attendance (the independent variable) is associated with an increase in associations with juvenile delinquents (the dependent variable). Lack of Plausible Alternative Explanations (p. 104) The third causal rule, lack of plausible alternative explanations, requires the researcher to eliminate all other reasonable causes before concluding that one variable causes another. Making Research Real 5.4 – What is the Cause of Truancy? (p. 104) A truant officer sets out to determine the cause of truancy. The officer finds that students with poor academic performance often become truant. The officer also finds a strong negative correlation – lower levels of academic performance lead to higher levels of truancy. Although the officer has established temporal order and correlation, he fails to consider alternative explanations like lack of attachment, bullying, lack of parental involvement, or parental supervision, all of which have a strong affect on truancy. Making Research Real 5.5 – Using Prior Research to Eliminate Plausible Alternative Explanations (p. 106) A racial profiling study finds that racial minorities are stopped in higher numbers than the drivers of other races or ethnicities. In this particular research the researcher was able to establish temporal order and correlation. Unfortunately the researcher was not able to discount alternative plausible explanations within this particular research. However, using similar research, wherein previous researchers had eliminated some of the alternative plausible explanations, the researcher gained insight into what explanations might be plausible. The Question of Spuriousness (p. 107) Spuriousness refers to a false causal finding. It occurs when a researcher alleges a causal relationship between two variables but fails to confirm at least one of the three causal rules. Making Research Real 5.6 – Can it Really be Too Hot to Swim? (p. 107) In this research a consultant determined that water temperature was the cause of an increase in drowning and near drowning incidents at a popular local beach. The researcher determined that the water temperature rose prior to the increase in drowning and near drowning incidents (i.e. temporal order). The researcher determined that there is a predictable relationship between water temperature and drowning and near drowning incidents. The relationship is positive. An increase in water temperature results in an increase of drowning and near drowning incidents. What the researcher failed to do is consider that fact (i.e. plausible alternative explanation) that more people swim during the summer months when the water temperature is warmer. Therefore the causal relationship between water temperature and drowning and near drowning incidents is spurious. Getting to the Point (Chapter Summary) Researchers use three causal rules to determine whether a causal relationship exists between two variables. Each of these three rules must be met before a researcher can prove that one variable is the cause of another. The first causal rule, temporal order, requires that the cause must precede the effect. In other words, the variable that is alleged to be the cause of another variable must happen first. The second causal rule, correlation, requires that the variables in a causal relationship be related to one another, or change together. A change in one variable must be associated with a change in another variable. Correlations can be positive or negative. The third causal rule, lack of plausible alternative explanations, requires the researcher to eliminate all other reasonable causes before concluding that one variable causes another. Spuriousness refers to a false causal finding. It occurs when a researcher alleges a causal relationship between two variables but fails to confirm at least one of the three causal rules.