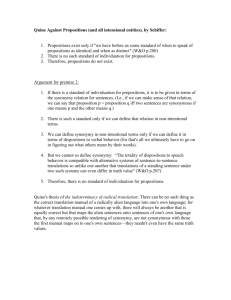

Introduction - Pete Mandik

advertisement

W&O: §§ 40 - 43 Pete Mandik Chairman, Department of Philosophy Coordinator, Cognitive Science Laboratory William Paterson University, New Jersey USA Chapter VI: Flight from Intension Brief Review of intension v. extension: Intensionality (with an ‘s’) = opacity = contexts in which co-referential or co-extensive terms or co-valued sentences are not intersubstitutable salva veritate Extensionality = transparency = contexts in which co-referential or co-extensive terms or co-valued sentences are intersubstitutable salva veritate 2 Feel the hate! Quine hates intensionality, thus his flight from it. 3 Sec. 40. Propositions and eternal sentences “A sentence is not an event of utterance, but a universal: a repeatable sound pattern. Truth cannot on the whole be viewed as a trait, even a passing trait, of a sentence merely; it is a passing trait of a sentence for a man. ‘The door is open’ is true for a man when a door is so situated that he would take it as the natural momentary reference of ‘the door’….Relativity to times and persons can be awkward…This is no doubt one reason why philosophers have liked to posit supplementary abstract entities--propositions--as surrogate truth vehicles….I find no good reason not to regard every proposition as nameable by applying brackets to one or another eternal sentence.”pp. 191-194 4 Eternal sentences “Eternal sentences are standing sentences (§9) of an extreme kind…Theoretical sentences in mathematics and other sciences tend to be eternal, but they have no exclusive claim to the distinction. Reports and predictions of specific single events are eternal too, when times, places, or persons concerned are objectively indicated rather than left to vary with the references of first names, incomplete descriptions, and indicator words.” pp. 193-194. 5 “A…humdrum reason for supposing that the propositions outrun the eternal sentences could be that for many propositions the appropriate eternal sentences, though utterable enough, just happen never to get uttered or written.” p. 194 “If a sentence were taken as the class of its utterances, then all unuttered sentences would reduce to..the null class…” p. 194 6 Solution: “We can take each linguistic form as the sequence, in a mathematical sense, of its successive characters or phonemes….We can still take each component character…as a class of utterance events, there being here no risk of non-utterance.” p. 195. 7 Sec. 41. Modality “Used as a logical modality, ‘necessarily’ imputes necessity unconditionally and impersonally, as an absolute mode of truth; and ‘possibly’ denies necessity, in that sense, of the negation.” p. 195 Examples: Necessarily, eight is an even number. Possibly, Frank eats a hoagie on Wednesday. 8 You can’t quantify into modal contexts In “There is an x such that necessarily x is greater than 4” the second x is in an opaque context: “necessarily, 9 is greater than 4” is true and “necessarily, the number of planets is greater than 4” is false even though the number of planets equals 9. 9 Perhaps we can treat modality as kind of attribute? So, we would get something like, the property of being greater than 4 is neccessary of 9. However, this “yields something baffling--more so even than the modalities themselves; viz., talk of a difference between necessary and contingent attributes of an object.”p. 199 10 Quine’s objection: Mathemeticians are allegedly necessarily rational and only contingently two-legged. Bicyclists are allegeldy necessarily two-legged and only contingently rational. “But what of an individual who counts among his eccentricities both mathematics and cycling?” pp. 199 11 Sec 43. Toward dispensing with intensional objects “A need to posit propositions…has been felt or imagined in a number of connections. Propositions or other sentence meanings have been wanted as translational constants: as things shared somehow by foreign sentences and their translations. They have been wanted likewise as constants fo so-called philosophical analysis, or paraphrase: as things shared by analysand and their analysantia. They have been wanted as truth vehicles and as objects of propositonal attitudes.” p. 206 12 “…it is a mistake to suppose that the notion of propositions as shared meanings clarifies the enterprise of translation.” p. 207 Because translation is indeterminate, there is no “uniquely correct standard of translation of eternal sentences” (p. 208) and thus nothing, on this account, for propositions as shared meanings to be. 13 “We come next to the appeal to propositions as truth vehicles. But instead of appealing here to propositions, or meanings of eternal sentences, there is no evident reason not to appeal simply to the eternal sentences themselves as truth vehicles.” p. 208 14 Quine’s arguments against positing propositions as objects for the attitudes comes in § 44. “Other objects for the attitudes”. 15 Study question: What’s Quine’s complaint against the notion of modality? 16 THE END 17