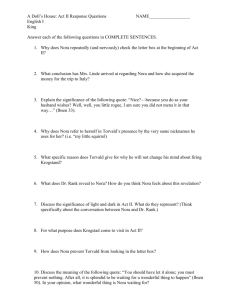

Parallels in A Doll's house analysis

advertisement

Parallels in A Doll's House William L. Urban Scholars have adequately documented what Henrik Ibsen intended A Doll's House to be when he first sat down to write: a study of the two different moral laws that the sexes are by nature required to follow, and the moral conflict that follows when women are judged by masculine standards (Meyer 1971:446). They also have established that in the course of the writing he abandoned the concept that the play was about gender roles. It was, instead, "the need of every individual to find out the kind of person he or she really is and to strive to become that person" (Meyer 1971:446 and Koht 1971:312-313). This interpretation of the play was slow in being accepted. The gender stereotypes that determined the role of women in the family and society as a whole were changing already, and the awareness of that caused Ibsen's contemporaries to see the gender motif as more basic than the search for individual fulfillment. In short, for them the play was Nora and her discovery that her gender role was an obstacle to her personal fulfillment. As it happened, changes in gender roles were already occuring so swiftly that not even Ibsen was ready for them. There was a famous incident in Rome when a runaway wife justified her abandoning husband and children for another man by saying that she had already done what Nora did. Ibsen retorted, "But my Nora went alone."1 In short, though Ibsen viewed himself as a revolutionary individualist, critics have been reluctant to look at his play as a statement about human condition. They would rather see a social criticism symbolized by the slamming of the door in the final act. What Ibsen himself thought of the play may be irrelevant. He was a difficult person to deal with, a man who loved to shock, to confound, and to get his own way; he was controversial and contradictory; and he was as eager to dominate his family and friends as Torvald Helmer ever ruled Nora--only Ibsen could not always get away with it. In short, he was as likely to give an interpretation that puzzled or shocked his listeners as he was to tell the truth; and since he changed his ideas in the process of creation, what he said later may not reflect his original thoughts. Also, he was willing to compromise his theme by rewriting the ending (having Nora stay with her husband) in order to get the production on the stage in Germany. An author is an artist, and it may be that the author is among the worst authorities to cite as to the significance of his work. In fact, Ibsen once argued that the audience must be trusted more than the author to provide a plausible explanation of the significance of a work of art, saying that "the play does not end at the fall of the curtain in the fifth act. The true end lies beyond; the poet indicates the direction in which we may seek; it is now up to each one of us to find his or her own way there."2 This is all the more important because Ibsen's written comments about the play that usually cited in program notes date prior to his having written the play. Since he made fundamental changes in both ideas and characters in his drafts, what he finally published was the product of evolutionary composition. This is more apparent to those who read the play as literature than to those who see it on the stage. Most theatre productions treat the play as Nora, using the minor characters as foils for a leading actress; in reading the play as literature, one has more time to see the ways Ibsen used parallelisms to give additional insights into Nora's character. This is an important point for those who adapt Ibsen's play for stage productions, particularly in making it into an attack on social stereotypes, because that which may be good theatre is not necessarily good literature. Theater may not be interested in the fullest significance of Ibsen's ideas, but producers should still be cautious in eliminating characters or changing their roles in an effort to "update" Ibsen. This has a similar implication for those who look at the play symbolically. Symbolism and social context have been examined thoroughly, with greatest success by George Bernard Shaw. But the symbolic approach assumes that the author had an intent (or an unconscious inspiration), which, once discovered, explains everything for the reader and the audience. Ibsen as a playwright is so complex that many critics find the symbolic approach limited. It is rarer that critics look through the text to see how the characters support each other. It has been noted that Ibsen's text of A Doll's House has no wasted dialogue and that every character, every line, has a purpose (Koht 1971:319). By looking at these characters, particularly at the way their personal histories parallel each other, we can better see what Ibsen intended us to learn. By looking at four parallels we can see the direction we should seek for a better understanding of the play. Afterward, we must make of it ourselves what we can. Nora and Kristina Linde Both Kristina and Nora chose the men they married by an intellectual rather than an emotional process: Kristina gave up the man she loved (Nils Krogstad) to provide economic security for her mother and her two younger brothers; Nora married Torvald Helmer at a time when he could have prosecuted her father for financial activities which were wrong if not simply illegal.3 Whether she married him out of thankfulness or to influence him during the time of decision is not clear, but one doubts that this timing was mere coincidence; if Nora married Torvald Helmer to save her father, we have reason to doubt that she was ever as empty-headed a "doll" as she claimed to be. Neither woman knew how to convey her thoughts and feelings to the man she loved: When Kristina broke off with Nils Krogstad, she believed she would spare him grief by ending the relationship ruthlessly and, necessarily, crushing the love he bore her. She was badly mistaken. In making him believe that she had thrown him over for a richer man, she drove him into crime. When she comes to visit Nora she has been on her own for three years and learned how to support herself. Moreover, she has become so aware of her own motivations and such an understanding of his that she comes to the town with the deliberate intent of speaking with her nowwidowed lover, and she is so beyond society's concept of what a woman should do and say in a courtship that she can begin the discussion of love and marriage with him. The audience can see that had she attempted ten years before to explain her motives honestly, she might have spared Krogstad a decade of suffering and personal tragedy. Nora, meanwhile is still so unaware of her own situation that she can remark to Dr. Rank, her real soul-mate, "You see, there are some people that one loves, and others that one would rather be with." She remarks that being with Torvald Helmer was like being with her father, and by the end of the play she knows that she does not love him, nor he her. There is no doubt that Nora loved Torvald once--for having risked everything to save her. It was her concern for his health that caused her to take out the original loan and forge her father's signature. Even as the play opens, however, she can see that physical attraction will not hold him much longer. She has begun to dream of a silly old gentleman who will leave her a lot of money in his will. Indeed, she almost asks Dr. Rank for the money to pay off the loan. She finds Dr. Rank good company, sexually attractive, and most important, a true friend to whom she can open her soul with few reservations. She can even curse in his presence and eat candy. Kristina sees the danger that lies in their association. Other women in Nora's situation could easily become the doctor's mistress--Nora suggests to Kristina that some "admirer" might give her presents--but Nora was still feeling a deep obligation to Torvald for having saved her father, and she was, after all, his wife. Would not many readers conclude that if Helmer were to die rather that the doctor, that Act 4 would present Nora as Mrs. Dr. Rank? Kristina Linde was freed from her unhappy marriage by just such a fortuitous death. Left without resources, she was forced into the world, made to earn her own way, to become her own person. Just as the bank offered her the opportunity for real business success, she told Nils Krogstad: "I must work or life isn't bearable. All my life I've worked--that's been my one great job. But now that I'm alone in the world I feel completely lost and empty. There's no joy in working for oneself. Nils. . . let me have something--and someone--to work for."4 At the end of the play Nora is beginning to sense the first part of the lesson that Kristina has learned fully. Nora must go out into the world and educate herself, which, in the context of the play, means to support herself. She has already discovered how much fun it is to support herself. She has already discovered how much fun it is to earn money, and she has been able to provide better clothes for her children and buy herself the occasional sweet. She knows she can do it, and now she must now do "My duty to myself." Later she will probably learn that she, too, has needs that can be met best in a husband and family. Whether that husband is Torvald Helmer or not depends on him, whether a man can, in his own words, "redeem his character if he freely confesses his guilt and takes his punishment," whether he can remove the mask that he wears "even with those nearest and dearest to him." Torvald Helmer and Nils Krogstad The least likeable character in the play is Torvald Helmer, who is sometimes portrayed as a sexist pig. Such a reading is too narrow and does an injustice to Nora and Dr. Rank, both of whom associate voluntarily with him. There is more depth to his character if one follows the hints that he had actively covered up for Nora's father. The first hint came when Nora told Kristina that Torvald had given up his government post because there was no prospect of advancement. It may be that there was no opportunity for getting ahead because promotion was slow in the bureau, but it may have been because his most intimate co-workers (those who would have used the familiar Du with him) were aware of what he had done. While the management did not prosecute him (just as Krogstad was not prosecuted), those acquainted with the incident could prevent his advancement into an office where his larcenous tendencies could do real harm. A second hint is that Helmer saw Krogstad as a threat to his new post in the savings bank: "he seems to think he has a right to be familiar with me." Did he suspect that Krogstad knew the one awful secret that could destroy him? The third hint follows that trail: Krogstad expected that Nora had sufficient influence to persuade her husband not to dismiss him. Why did he believe this unless he had some suspicion of her past influence? A further hint comes when Helmer remarks: "I pretend we're secretly in love--engaged in secret--and that no one dreams that there's anything between us." Why does he want that? Is this not a reference to the conflict of interest regarding her father? Lastly, after reading Krogstad's letter, almost immediately Nora's father comes to mind; he exclaims, "So this is what I get for condoning his fault! I did it for your sake, and this is how you repay me. . . . You've completely wrecked my happiness, you've ruined my whole future. . . . I may very well be suspected of having been involved in your crooked dealings. They may well think that I was behind it--that I put you up to it."5 Helmer did not want to confront his own dishonesty, and in his efforts to cover up his past, he put all the blame on Nora and her heredity. Once, long ago, his lust for Nora was stronger than his desire for social and economic status. That is no longer the case. She can no longer influence him, not even by promising to do all her "little tricks." He even spends so much money on his own clothes that Nora has to work secretly to buy the children new clothing. Now Helmer's long work and sacrifice are beginning to pay off: after eight years as a struggling lawyer, he has just been appointed manager of the savings bank--a post that would not be available to anyone with the slightest history of dishonesty. Torvald Helmer has never been able to have a serious conversation with Nora. Is it that he could not risk having the subject of Nora's father come to the surface except as a rebuke for her childishness? He was only able to deal with Nora as a doll because if he dealt with her as a person, he would first have to come to terms with himself and his failure to live up to the moral codes of his society and his profession. As he said at the end of Act One: "An atmosphere of lies like that infects and poisons the whole life of a home." He has made himself so blind to the truth that when he speaks of Krogstad's crime and of Nora's father's weaknesses, he concludes with a denunciation of the mother's influence. Yet neither Nora nor Krogstad's children have a mother! Ibsen makes clear that the fault is the father's--but when he thus blames Helmer for the failure of the marriage, Ibsen is not condemning him for shallow selfishness, but for an unwillingness to face the truth. Kristina can see how Nora's failure to face the truth endangers the marriage, but she does not know what Helmer is hiding. Nora realizes how selfish Helmer is after he reads Krogstad's letter promising not to reveal the loan or the forgery. When he sensed that his past could be covered over again, Torvald exclaimed: "I'm saved." Not "You're saved," or even "We're saved," but only "I'm saved." Nora saw that she had been living for eight years with a stranger. She knew that Helmer did not love her, that he was no longer willing enough to risk himself or his reputation for her. That freed her of all obligations to him. Nora not only had to leave to save herself as a person, but now she was morally free to go into the world on her own; this also gave both her and Torvald the opportunity "to be so changed that. . . our life could be a real marriage." Torvald Helmer was dumbfounded. He did not know what she was talking about. How Torvald Helmer will face this is problematic. His best friend, Dr. Rank, who early in the play knew him better than Nora did, had said that Helmer was too sensitive to face anything ugly. This moral collapse was far uglier than the doctor's illness. The reader must wonder if Helmer has the courage to face the townspeople when they learn that Nora has left him, whether he will learn accept hardship and begin to live for others. Will he, like Nils Krogstad, live for the reputation of his children, come to terms with himself, and strike out with a determination to make himself anew. Will he learn that a real marriage is such a fundamental need that a man must be willing to make the same sacrifices that woman make? He is not now the man who can teach Nora to be a wife. Can he become that man?6 Nils Krogstad, in contrast, has come to terms with his past dishonesty. He admits that he had made a mistake many years ago in trying to make money through forgery (a parallel with Nora) and through unscrupulous business activities, but he argued that he has paid for his error: until eighteen months ago every way forward in his profession had been closed to him.7For almost eight years he had been a loan shark and a sensational journalist. Then, apparently right after being widowed, he took stock of himself and his responsibilities. In order to win back as much respect in society as he could, so that his young sons would have a chance in life, he had abandoned his pursuit of money; moreover, someone had been willing enough to take a chance on his reformation that they had offered him a job as clerk in the bank. Now Helmer comes in as the new manager and fires him. Krogstad's only chance for respectability (the parallel to Helmer) is to return to the bank. He knows that he is, in Dr. Rank's words, "a moral invalid," a "shipwrecked man clinging to a spar." But he can be saved--and not by the job at the bank. Kristina is the love he thought he had lost because he was poor. Now she can be his, if only he will remain steadfastly honest. With her he can overcome any obstacle, even the loss of his job and his money. She is the wife he needs, the mother for his children. He recognizes this almost instantly, and the audience recognizes it, too: Krogstad's sudden conversion is utterly believable. That Ibsen can have Krogstad, the loan shark and extortionist, give away the bond for $1200 and his last hope of holding his post at the bank, and be believable, is one of the supreme achievements in the history of playwriting. Nora and the Nurse The nurse, Anna Maria, was Nora's nanny, the woman most important in her upbringing and her closest companion. In what might pass for a comparatively unimportant scene, Nora asks a very critical question from the woman she trusts the most: would her children forget her if she went away? The nurse herself had been forced to choose once between rearing her own child in poverty and accepting work as Nora's nanny; she had chosen to give her (illegitimate?) daughter to strangers, presumably assisting from time to time with small gifts saved from her meager salary. The nurse was reassuring: her daughter had not forgotten her--she had been reared as a Christian woman and made a good marriage. Nora knows that Anna Maria will care properly for her children should she come to make a decision that she cannot yet even put into words. How could any woman named for the two holiest mothers not be entrusted with children? Nora herself is a good playmate, but she is not a good mother; she cannot be one until she grows up; and she surely recognizes now that she is sinning against them. She will surely corrupt them unless she leaves. The nurse's lesson is clear: sometimes a woman must make choices between unsatisfactory alternatives, but she can live with the consequences of her decision. Life is not all happiness, but neither is it all despair. Things do work out. In Nora's case, particularly, a woman can escape being trapped by conventional responsibilities into accepting the destruction of her pride and her personality. The sins of one generation are visited on the next Most audiences take the fate of Dr. Rank literally as another condemnation of male sexual conduct. Not often is it realized that his impending death from congenital venereal disease is necessary to the plot: it informs us that Nora cannot be having an affair with Dr. Rank and she cannot run to him after slamming the door. The parallel between his fate and that of the two women is more important that the fact of V.D. Nora and Kristina are as trapped by their fathers' actions as he is: both fathers failed to provide for their families, so that the daughters had to sacrifice themselves to save the situation. Both were treated like "dolls" and left unprepared for life. Dr. Rank makes this clear: "In one way or another there isn't a single family where some such inexorable retribution isn't being extracted." If Dr. Rank's father had been more honest and concerned for the future, he could have sought treatment for his condition. But he apparently ignored his illness and went on his way to infect his wife and his child. Kristina's husband left her unprepared for life's dangers, too, and Helmer would not even entrust Nora to open the mailbox. Nora's daughter was apparently destined to suffer the same fate. The women, like Dr. Rank, became aware of their condition very late. For Dr. Rank, like many women, it was too late to take measures. For Nora there is still time. It is in this context that the conversation of Kristina Linde and Nils Krogstad makes sense: Nora must tell Helmer the truth. It is the lie that hurts, it is the lie that has such unforeseen consequences later.8 If the truth emerges, there is likely to be a scandal. Nevertheless, the cycle of lies and foolish sacrifices must end somewhere.9 Kristina says, "Nils, when you've sold yourself once for the sake of others, you don't do it a second time." Nora has already sacrificed enough for her father, her husband, and her family. She must now be ready to do something for herself. Conclusion The play is not just about Nora. The supporting characters are important in themselves because they face the same type of problems that Nora does-especially the need to face the truth in personal relationships. Their problems illustrate the basic theme and bring out aspects of Nora's character that are essential to understanding her more fully. Furthermore, we can see hints in the parallels about what the future may hold for Nora. Like Kristina Linde, she must earn her way in the world, gathering experience for that worthwhile life she senses is possible. Like Kristina in a few years she will probably come to the conclusion that life cannot be lived for oneself alone. Meanwhile, she is certain that her children will be properly cared for. Having slammed the door, she will go to Kristina Linde for the night, then to her father's hometown, where she will seek work. When she finds out who she really is, when she has had some success, she will return to seek out Helmer. She has already said, "As I am now, I'm not the wife for you." She may yet become that woman. Perhaps Torvald Helmer will make an equal growth in character. (Nora says that he can change if his "doll is taken away.") If he has made the same growth that Nils Krogstad had made, Torvald and Nora will come back together; if he has not repented and made himself new, our new Nora would be foolish to return to A Doll's House.10 Works Cited Brandes, Georg. 1964. Henrik Ibsen. A Critical Study. New York: Benjamin Blom. Reprint of 1899 edition. Clurman, Harold. 1977. Ibsen. New York: Macmillan. Davies, H. Neville. 1982. "Not just a bang and a whimper: the inconclusiveness of Ibsen's A Doll's House." Critical Quarterly 24:33-34. Heiberg, Hans. 1967. Ibsen. A Portrait of the Artist. Coral Gables, Florida: University of Miami. Koht, Halvdan. 1971. Life of Ibsen. New York: Benjamin Blom. Meyer, Michael. 1971. Ibsen. A Biography. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday and Company. Northam, John. 1965. "Ibsen's Search for the Hero." Ibsen. A Collection of Critical Essays. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. Notes 1. Meyer (1971:470). 2. See Meyer (1971:148) for Ibsen's own views, that society is essentially male and does not understand that there are two types of spiritual law, two kinds of conscience. See also Koht (1971:316 and 322) and Heiberg (1967:203-204). 3. This seems to have been overlooked by contemporary and modern critics. Most critics see Helmer as an honest man, too concerned with propriety. See Clurman (1977:100f, 115). 4. The best description of this subplot and love story is Davies (1982:33-34). 5. Clurman (1977:115, 117). Brandes (1964:77-78): "The man is thoroughly honourable, scrupulously upright, thrifty, careful of his position in the eyes of strangers and inferiors, a faithful husband, a strict and loving father, kindhearted. . . ." 6. Brandes (1964:49) says that Ibsen views Helmer as a stupid and evil man, whose "stupidity arises solely from his self-righteous egoism." 7. Clurman (1977:115-116) presents the traditional interpretation of Krogstad: "a soft man driven to hardness." 8. Northam (1965:103f, 108) sees Rank as the symbolic representation of Nora's moral illness. 9. If in this play Nora and Torvald's lies undermine their marriage, in other plays Ibsen comes to the opposite conclusion: the "life lie" is sometimes essential. Stockmann tells the truth and is hounded out of town, Hedda cannot face the truth and kills herself. 10. Clurman (1977:118):"We may sentimentally hope that Nora and Torvald may sometime in the future mend their marriage, but Ibsen certainly does not encourage it." Davies (1982:35), on the other hand, in remarking on a wide variety of lerned guesses about Nora's fate, notes that the subplot of Kristina and Nils provides hope for miracles in life.