Modern Drama Collaborative Analysis

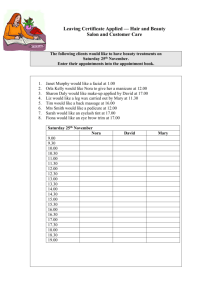

advertisement

1 Liz Bonnett, Tess Davis, Erin Halterman, Mariah Anderson, Alaina Stills Ms. Grissom AP Lit 27 February 2014 A Doll House When Henrik Ibsen published his play, A Doll House, in 1879 in Denmark it offered controversial and revolutionary ideas regarding gender roles to its 19th century audience. Ibsen first presents his main characters, Nora and Torvald Helmer, as the stereotypical gender types: Nora is the immature, helpless woman and her husband the patronizing head of the household. As the story unfolds, the audience begins to understand the depth that lies beneath Nora’s facade. Ibsen implements the traditional components of a tragedy in A Doll House. In order for a piece of literature to be considered tragedy, it must contain certain plot components such as a scene of suffering, a moment of recognition, and a reversal in the situation. The hero of a tragedy should be depicted as better than life in some way and must possess a tragic flaw that leads to their downfall. All of these components are used together to achieve the main goal of any tragedy: to incite pity and fear in the audience. In A Doll House, Ibsen touches on all of these components in some way. Though certain aspects are weaker than others, his inclusion of every component makes A Doll House a clear, but imperfect, tragedy. His development of Nora’s character serves as the focal point of the play. In Nora, Ibsen creates a character who is torn between fulfilling society’s expectations and following her own moral compass. In this tragic play, Ibsen uses the characterization of Nora to emphasize the gender roles of women in the 19th century, and the urge many of them felt to overcome these societal expectations. In the beginning, Nora is characterized by society’s definition of women in the 19th 2 century. She is depicted as a woman who submits to her husband and is uneducated. One way Ibsen shows this is through the way that Nora’s husband, Helmer, treats her. The first thing we hear from him in the play is him calling to Nora, “Is that my little lark twittering out there?” (1710). Next, we hear from him, “Is that my squirrel rummaging around?” (1710). Helmer uses these, among other “pet names”, throughout the play when talking or referring to his wife. The fact that he names her after animals typically known as innocent, carefree, and unintelligent is crucial to the characterization of Nora. Squirrels, in particular, are considered by most people to be ignorant, cute, and harmless. Squirrels are lesser than humans in the food chain. This is symbolic for the fact that women are lesser than men in the social class standings of the late 1800s. Also important in Helmer’s treatment of Nora is his willingness to give her things. “Spendthrifts are sweet, but they use up a frightful amount of money. It’s incredible what it costs a man to feed such birds.” (1712). This makes the reader believe that Nora is careless and clueless with her money, and also relies on her husband for everything. This was how society was supposed to be: women were supposed to be completely submissive and relied on their husbands. Nora further reinforces this by saying, “You know I could never think of going against you.” (1712). Nora could not go against her husband--- her duty was to be submissive to him. A few pages into Act I, Mrs. Linde, a childhood friend of Nora’s, comes to visit. Mrs. Linde helps to emphasize Nora’s character, and the audience can easily become annoyed with Nora in this scene. Mrs. Linde tells Nora about her newly widowed state and how she was left behind with nothing. Nora is sympathetic, but in a way that is superficial. She says, “So completely alone. How terribly hard that must be for you. I have three lovely children...” (1714). She continues on about her children, who are being cared for by the maid. Nora then realizes she is going off track and says, “Today I don’t want to be selfish.” (1714). But, even then, she continues 3 to talk only about her own life. While the reader can conclude that Nora does feel sorry for Mrs. Linde, Nora cannot empathize. This shows the audience that Nora struggles to feel true sympathy for a situation she can’t understand: she is awkward in situations that require deep emotional thought because she is not typically expected to be anything deep in her daily life. One can assume that Nora is not used to facing hardships and has never dealt with the things to the capacity that Mrs. Linde has. A widow in that time period was left behind nothing. Nora cannot even fathom what it was like to have nothing, because she was raised by a rich man and married a rich man. Her life has been consistent. Nora quickly moves on to talk more about her life, how her husband is a lawyer and because of that she gets “stacks and stacks of money.” Mrs. Linde calls her a “spendthrift” and refers to their childhood days when Nora was a “free spender” (1714). This further emphasizes the role of women in society. Nora appears to have spent her life feeding off of her father’s money, and then her husband’s money. It appears as if she has never worked for her own money, which was the norm for society in the 1800s. She appears to know nothing of finances and budgeting money. That was also the norm because financing and budgeting was solely the man’s job. Ibsen then surprises the audience when he shatters the notion that Nora is a simple, normal woman of the late 1800s society. Nora tells Mrs. Linde a secret that could potentially destroy her marriage and husband’s reputation: She took out a loan herself to pay for a trip to Italy to save her husband’s life (1725). While this may seem normal by modern society’s standards, back then, not only was it unheard of, it was illegal. On top of it all, Nora forged her father’s required signature as a co-signer of the loan three days after his death. Even in today’s society, a forgery of a signature is illegal. Krogstad, a bank employee,the one who helped her with the loan, assuming it was truly signed by her father, figures out her secret (1726). She wasn’t worried by what she had done 4 though because she felt it was morally right to break the law in order to save her husband’s life. Though Nora was ignorant of all the possible legal repercussions for forgery prior to Krogstad’s threat, her willingness to think deeply afterward about the difference between what is moral and what is legal show that she is so much more than her previous characterization. For Nora to be a tragic hero she must be better than life. Nora must be morally better than the average person. This is evident when Krogstad is blackmailing Nora after she forged her father’s signature to save her husband. Nora believes that she did the right thing even when she broke the law. Krogstad says“laws don’t inquire into motives” which Nora replies, “Then they must be very poor laws,” showing that Nora truly thinks that she is in the right and that the laws are wrong (1726). Nora stands up for what she thinks is right even when the other characters in the play think she has done an unlawful thing. Helmer sees what Nora has done as so horrible that he says, “But you can’t be allowed to bring up the children; I don’t dare trust you with them,” truly believing that Nora is unfit to raise the children after she lied to him about everything (1752). Nora knows in her heart she did the right thing and that’s why she leaves Helmer in the end because he admits“And I don’t understand you,” not understanding her or seeing what she did to save him as morally right (1753). The tragic flaw in Nora is that she is loves her husband too much and was willing to do anything for him. The only reason that she forged her father’s signature was so that she could save Helmer’s life without worrying him. She did not want her husband to be embarrassed knowing that he was in debt to her. She also didn’t want to worry her father about the signature, since he was ill. She was simply doing what she thought was best. Helmer says, “You loved me the way a wife ought to love her husband. It’s simply the means that you couldn’t judge.” (1752). She was doing the right thing to save her husband’s life, she just didn’t do it in the right way. She chose the love 5 for her husband over what society thinks of her. “It is true. I’ve loved you more than all this world.” (1751). She was willing to do anything for the man she loved. Nora’s characterization and depth to her true character changes in Act II. Dr. Rank, a close family friend who is dying, confesses his love to her, saying he would gladly give up his life for Nora (1736). Nora tells him that “there are some people that one loves most and other people that one would almost prefer being with” (1737). The reader can interpret this, knowing the ending, that Dr. Rank has made her come to a realization (somewhat) that perhaps her marriage with Helmer isn’t as genuine and deep as Dr. Rank’s love for Nora is. Nora helps to emphasize the depth of their relationship by saying, “[I trust you] More than anyone else. You’re my best and truest friend, I’m sure” (1736). Nora enjoys Dr. Rank’s company, he is a male that likes her for who she is, not what he wants her to be. This is further emphasized when Nora says, “When I was back home, of course I loved Papa most. But I always thought it was so much fun when I could sneak down to the maids’ quarters, because they never tried to improve me…” (1737). While Nora denies that Dr. Rank has filled that position, he has, in a sense. She has said that she prefers being with him over Helmer sometimes. Dr. Rank is her best friend, not just a doll to her. Nora even further emphasizes this when she says, “But you can understand that with Torvald it’s just the same as with Papa-” (1737). Now the reader is coming to terms with Nora’s mind. While Nora may not have come to full terms with her situation and her decision to leave at the end of the play, she has realized that she has been passed on from her dad to Helmer in the sense that they both make her who they want her to be, as she had said to Dr. Rank earlier. The beginning of Act III is when the reversal happens in the play. Nora wants Mrs. Linde to get Krogstad to take his letter back before Helmer has a chance to read it because she knows that it will reveal all her secrets to her husband. Instead of Mrs Linde telling Krogstad to 6 take the letter back she tells him “No, Nils, don’t call the letter back” so that Helmer will read it (1745). This would normally be a good thing for Nora’s marriage because then there would be no secrets between them. Mrs. Linde says, “Helmer’s got to learn everything; this dreadful secret has to be aired; those two have to come to a full understanding; all these lies and evasions can’t go on” so she even believes that this will be a good thing for Nora (1746). Helmer finding the letter is actually catastrophic for Nora and her marriage. From this point forward Nora recognizes that her marriage is over. By the end of the play, Nora has accepted that Helmer will inevitably find the letter that has been left by Krogstad to expose her secret. Up until this point in the play she has been scrambling to keep the truth hidden from her husband and preserve their marriage, coming up with every excuse possible to distract him from opening the letter. She pleads with him to stay later at a party that night: “Oh, I beg you, please, Torvald. From the bottom of my heart, please---only an hour more!” (1746) Nora’s attempts to avoid the impending disaster fail. Helmer brushes her off and does not take her desperate wishes seriously. After a surprise visit from Dr. Rank, Helmer goes to get the mail. In it he discovers a card from Dr. Rank with a black cross over his name. “He could almost be announcing his own death,” Helmer says (1750.) Nora explains to him that Dr. Rank is dying and they probably will never see him again. Nora is only telling the truth and isn’t attempting to manipulate Helmer with this fact. Ironically though, this honest and unplanned conversation is what gives Nora the opportunity she’s been fighting for all night: Helmer is distracted and no longer thinking about the mail. Throughout the entire play, Nora has been conflicted and torn between the fear of angering her husband and her strong belief that she has done nothing wrong. Ibsen makes Nora’s choice clear and decisive when she declares, “Now you must read your mail, Torvald” (1750). This shift in Nora’s character signifies the gradual end to 7 her act as the submissive housewife as she takes ownership of her actions. The moment of recognition in A Doll House comes with Helmer’s reaction to the condemning letter revealing all the things that Nora had done. Nora’s expression “hardens” as she tells her husband that she is “beginning to understand everything now” (1751) when Helmer reacts selfishly to discovering the letter, screaming that Nora had “wrecked all [his] happiness” and “ruined [his] whole future.” (1751) This reaction is very telling of Helmer’s character. Just prior to opening the letter, he was telling her “You know what, Nora--- time and again I’ve wished you were in some terrible danger, just so I could stake my life and soul and everything, for your sake,” (1750). Now the opportunity has presented itself---Nora is in significant legal danger--- and instead he is only concerned of his own future. In reality, Nora was the one in the relationship who was willing to risk her “life and soul and everything” for Helmer, when she took out the loan with a forged signature in order to save him. Then, after receiving a second letter containing an apology from Krogstad, he exclaims “I’m saved. Nora, I’m saved!” (1752), showing no regard for how his wife is affected by the situation, to which Nora replies “And I?” This simple response shows Nora’s awareness of her husband’s lack of concern for her emotions. Nora is angered when Helmer abandons his role as her protector and cares only about how her actions will affect him. This is a huge moment of clarity for Nora and as she is left to face the truth of their relationship, she states “We’ve been married now eight years. Doesn’t it occur to you that this is the first time we two, you and I, man and wife, have ever talked seriously together?” (1753) Nora’s characterization no longer includes any trace of ignorance or vanity. As Nora comes to terms with this realization, she finally confronts Helmer about his treatment of her, saying that “You never loved me. You’ve thought it fun to be in love with me, that’s all” (1753). The scene of suffering in A Doll House takes place at the end of the play when 8 Nora makes the choice to leave her children and Helmer. “Never see him again, Never, never. Never see the children either-- them, too. Never, never. Oh, the freezing black water!” (1750). She had to make the choice to either conform to the gender role of society or find her value of individuality. She doesn’t want to leave her children, but she feels as if she would be poisoning them if she stayed. Helmer tells her, “Because that kind of atmosphere of lies infects the whole life of a home. Every breath the children take in is filled with the germs of something degenerate.” (1728). At the point that Helmer says this she is starting to feel like she is failing as a mother. She also feels like she is a burden to her husband. “When I’m gone from this world, you’ll be free.” (1751). She says this to Helmer after he reads the letter. She knows that even though it will be hard, she needs to go on with life by herself. She is not only suffering while making the choice to leave, but after she leaves she will never be treated the same. In that time period, it was not okay to leave your children. When Nora goes out on her own, everyone will treat her differently. Her suffering will last the rest of her life. Helmer is distressed by Nora’s behavior and is pleading with her to stay. Though he is angry and confused, his offerings to change show that he is not the antagonist of the story but rather the victim of his society’s expectations. Both he and Nora were playing the game of stereotypical wife and husband like they thought they should, and unfortunately fulfilling their assigned roles lead each to their own misery. Nora, however, takes this insight and decides to leave. The play ends with her walking out on her family--- a final abandonment of the expectations of her society and a final warning from Ibsen of the detrimental effects of gender roles. Nora is driven by her strong moral compass and values morality over law, and despite her many attempts to do the right thing throughout the play, everything she does seems to backfire. In this way, Ibsen creates a character that audience members will pity. The audience also pitys Nora 9 because she is a nice, caring person and people don’t like to see bad things happen to good people who they relate to. Nora shows that she is a caring person by helping Mrs. Linde, “Just leave it to me; I’ll bring it up so delicately-find something attractive to humor him with. Oh, I’m so eager to help you” get a job at Helmer’s work (1716). Ibsen also instills fear in the audience by showing that sometimes what is legal and what is right is not the same, making them worry that someday, they may be in a similar moral dilemma that forces them to choose between doing what is lawful and what is right. The audience feels fear when it comes to Nora’s downfall.When the audience notices that Nora is completing leaving her family “Do you think they’d forget their mother if she was gone for good?” they begin to fear that if they try have strong morals that it may jeopardise their family (1729). Through the inclusion of all tragic elements, Ibsen’s A Doll House undoubtedly should be considered a tragic play. Ibsen has all the essential parts of a tragedy in a more modern manner. He uses Nora as a tragic hero battling the gender roles of the 19th century. Ibsen shows through the characterization and development of Nora the detrimental effects of gender roles in the 19th century and the expectations they placed upon women. 1 0 Works Cited “The Dramatist: Henrik Ibsen.” mnc. Bjorn Hemmer, n.d. Web. 12 Feb. 2014. Ibsen, Henrik. “A Doll House.” The Bedford Introduction to Literature. Ed. Michael Meyer. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2011. 1709-1757. Print. Wojtczak, Helena. “Women’s Status in Mid 19th-Century England.” Women of Victorian Sussex. Hastings Press: 2003. Web. 20 Feb 2014. Research Reflection 1 1 This play was published in 1879. It was premiered in Denmark. During that time in history, men were the money makers of society: they ran the businesses, made all of the money in the family, and were the dominant figure in society. Women were married at a young age and lived their lives serving for their families. Men had every right to force their wives into sex and childbearing. Their clothing was symbolic to their lives: it was tight, corseted, and huge. During this time, there was a rising gap between the rich and the poor. Middle class and social reformers sought to reform labor and to bring about equal opportunities for everyone. The European women’s rights movement was inspired by American women’s right movements. Approximately at this time was the Seneca Falls Convention (1848). In Denmark and the surrounding European areas, they had their “first wave feminist movements.” A main concern at the beginning of the movements was divorce: women should be allowed to divorce their husbands if they are in an unfit marriage. Another thing they wanted was equality in the workforce with men, and access to elementary education rose for women, as did access to higher level education. Many women became teachers. Starting in 1890, the women’s rights movements really took root and made a lot of progress, in both America and Europe. The women at this time (in the United States) were angered by the fact that African Americans were starting to gain rights, and they still hadn’t achieved much in the legal world Henrik Ibsen was born March 20, 1828 in Norway. He was the oldest of 5 children. His father was a merchant and his mother was a painter. At 8, his family was in poverty. He stopped school at 15 and went work, where he started writing poems. He has written over 300 poems. He wrote his first play in 1879 and was often referred to as “the father of realism.” When he wrote A Doll House in 1879, he did not consider it a feminist piece of work. He was considered a scandalous writer because his play challenged the normal model of family life. He was married to 1 2 Suzannah Daae Thoresen in 1858. They had a happy marriage and one son, Sigurd. Ibsen also had another son with a maid in 1846, before meeting Suzannah, but never met him. He died May 23, 1906. His last words before he died were “To the contrary.” Overall, we believe that A Doll’s House is a tragedy, but a flawed and inconsistent one. The traits that make a character a tragic hero are faint and sometimes hardly detectable in Nora, but are definitely present overall. The plot aspects of tragedy are stronger and better developed than the character traits. To come to an understanding that falls within the cone of rightness, readers must keep the historical context of the work in mind. If the reader fails to do so, it is easy to come to a conclusion that is shaped by modern society and takes on a totally different meaning. The play’s commentary on individuality and autonomy make it relevant and meaningful to the modern reader. Responsibility Designation: Liz: Historical research, analysis of the theme, works cited Tess: Analysis of tragedy, works cited, analysis of research Erin: Analysis of tragedy, works cited, biographical research Alaina: Analysis of theme, flow/editor, analysis of research 1 3 Mariah: Analysis of tragedy, reflection writer