Development and Interpretation of Long

advertisement

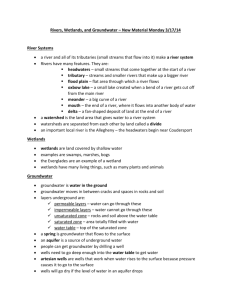

Development and Interpretation of Long-Term Water Data: When is Long-Term Long Enough? Peter Thibodeau, Ph.D., P.G. David Dickson For the 2011 Alabama Water Resources Conference Organization Introduction The problem: Data Needs vs. Data Availability Approaches to address long-term water data needs – Surface water – Groundwater – Post-construction validation Summary The Problem: Do we have the data we need? Evaluation of proposed projects in undeveloped or “under-” studied areas Time scale of concern – defining the frame of reference Available sources of information Technological advantages – – – – GIS AutoCAD Raw computing power Database availability (USGS, STORET, state and university databases) Once we have framed the problem, we can look at the pathways for solving the data needs Do we have enough data? Are they “good” data? “That system is designed to handle a 2-year storm. You know, that happens 2 or 3 times a year around here”. ---name withheld “Typically, we evaluate stream effects on a decade time scale. You don’t have 10 years of data for that particular stream segment, so start collecting …” ---name withheld “How can you convince me that this was the storm of record, just because it was the largest storm we have data for?” ---name withheld What problems are we trying to answer? Framing the problem is essential Don’t over-scope the solution Statistical analysis options Relevance to assessing impacts or flow regime changes Ultimate goal: defendable decisions using appropriate data When data are not available for the study area What streams/rivers in the area are/have been monitored? Analytical approach: simple to complex solutions – – – – Mathematical relationships Land cover Land use and GIS solutions Streamstats Groundwater monitoring data Data are available, but not the right time period Flow record extension techniques – Analytical methods – GIS methods Watershed adjustments for land use/cover – GIS methods Similarity of watersheds – GIS methods Stochastic events (storms and droughts) Groundwater correlations as a tertiary tool http:Image obtained from //www.cleanwaterpartnership.org/alabama-river-basins/ Index wells for groundwater evaluation Working with state agencies to ID and accept discrete wells as representative of area conditions Changes in index well water levels are representative of changes for sites within a defined area Used to estimate impacts and acceptable water level variations The “Frimpter Method” (USGS, 1981) Trend analysis of temporal changes Trend analysis of regional water availability: groundwater and surface – Temporal analysis used for water supply planning – Spatial trends in water level changes due to development pressure – Groundwater flow modeling analysis Aquifer to aquifer comparisons Limited capabilities Uncertainties and heterogeneities Possible depending on scale of the problem Image obtained from USGS Scientific Investigation Report 2010-5080 Image obtained from http://www.gsa.state.al.us/gsa/geologichazards/sinkholes/lscrops.gif Post-Development and Validation Getting out of the computer Field observations Real-world validation and checks on calculations, statistical analysis, and modeling Opportunity to revise and re-scale if needed Future use of calibrated and validated data Project Example: Wetland Mitigation Greens Creek Mitigation Bank – Clay County, Florida Project size: ±4,400 acres Hydrologic improvements to restore impacted wetlands and generate points of lift. Impacts to hydrology were from silviculture (bedding rows and planted pines in historic wetlands) and ditches. Wetlands and groundwater were being drawn down. Goal was to restore site to pre-agriculture conditions. Challenges: – – – – – Minimal on-site historical data No off-site effects/impacts allowed Economics In a drought Timeline Project Example: Wetland Mitigation Restoration plan – Installed piezometers to document current conditions (collected 10 months of data prior to permitting). – Identified target community types and selected representative communities nearby to document proposed conditions. – Collected representative site specific topographic data. – Collected available historical data for region. – Utilized computer model to design improvements. – Defendable decision – prove hydrologic improvement for plan approval. Post Construction – Collect groundwater data for 5 yrs to compare with pre-construction conditions – Annual monitoring to measure success criteria and allow for adjustments Results – Verify assumptions and validate the long-term water conditions as estimated from permitting process. Summary Framing the problem is essential to a good study Use available data to the extent possible Determine reliable extension methods based on specific site conditions Surface water techniques Groundwater methods Validation and getting out of the computer Defendable decisions using appropriate data Thank You Peter Thibodeau, Ph.D., P.G., P.H. Cardno ENTRIX Raleigh, North Carolina 919-999-4008 Peter.thibodeau@cardno.com David Dickson Cardno ENTRIX Tallahassee, Florida 850-681-9700 David.dickson@cardno.com