A Collection of Templates for Slide Presentations

advertisement

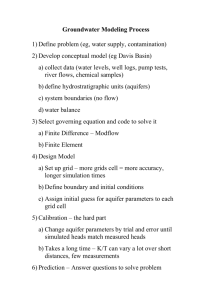

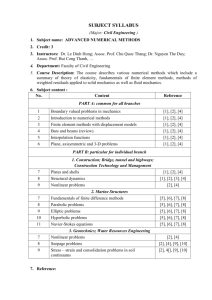

SDSU GEOL 651 - Numerical Modeling of Ground-Water Flow SDSU Coastal Waters Laboratory USGS San Diego Project Office 1st Floor conference room 4165 Spruance Road San Diego CA 92101-0812 Tuesdays 4 -7 PM Introductions • Claudia C. Faunt • Ph.D. in Geological Engineering from Colorado School of Mines • Hydrologist with U.S. Geological Survey • (619) 225-6142 • ccfaunt@usgs.gov • Office 2nd floor NE corner Introductions • • • • Please introduce yourself explain who you are where you are from what your current endeavor is (for example, MS student; state government hydrologist; or consulting hydrologist) • explain why you would like to learn more about ground-water modeling (knowing your motives helps me improve the class) Course Organization • Organizational Meeting – Part of the first class meeting will be dedicated to an organizational meeting, at which time a general outline of the class topics, and any desired changes in schedule will be discussed. • Grading (details next week) – 25% miscellaneous assignments – 25% paper critique assignment – 50% final project (paper and presentation) • Syllabus Course Organization • Classes – First few mostly lectures – Majority • First half lectures • Second half – Problem set related to lecture – Model project work Course Topics • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Introduction, Fundamentals, and Review of Basics Conceptual Models Boundary Conditions Analytical Modeling Numerical Methods (Finite Difference and Finite Element) Grid Design and Sources/Sinks Introduction to MODFLOW Transient Modeling Model Calibration Sensitivity Analyses Parameter Estimation Predictions Transport Modeling Advanced Topics including new MODFLOW packages Others? Tentative Syllabus (subject to change to adjust our pace) • Handout Introduction to Ground-Water Modeling OUTLINE: • • • • • • • What is a ground-water model? Objectives Why Model? Types of problems that we model Types of ground-water models Steps in a geohydrologic project Steps in the modeling process What is a ground-water model? • A replica of a “real-world” ground-water system OBJECTIVE: • UNDERSTAND why we model ground-water systems and problems • KNOW the TYPES of problems we typically model • UNDERSTAND what a ground-water model is • KNOW the STEPS in the MODELING PROCESS • KNOW the STEPS in a GEOHYDROLOGIC PROJECT and how the MODELING PROCESS fits in • KNOW HOW to FORMULATE & SOLVE very SIMPLE ground-water MODELS • COMPREHEND the VALUE of SIMPLE ground water MODELS Why model? • SOLVE a PROBLEM or make a PREDICTION • THINKING TOOL – Understand the system and its responses to stresses Types of problems that we model • • • • • WATER SUPPLY WATER INFLOW WATER OUTFLOW RATE AND DIRECTION CONCENTRATION OF CHEMICAL CONSTITUENTS • EFFECT OF ENGINEERED FEATURES • TEST ANALYSIS Types of ground-water models • • • • • CONCEPTUAL MODEL GRAPHICAL MODEL PHYSICAL MODEL ANALOG MODEL MATHEMATICAL MODEL • We will focus on numerical models in this class Conceptual Model • Qualitative description of the system – Think of a cartoon Graphical Model • FLOW NETS – limited to steady state, homogeneous systems, with simple boundary conditions Physical Model • SAND TANK – which poses scaling problems, for example the grains of a scaled down sand tank model are on the order of the size of a house in the system being simulated Sand Tank Model Analog Model • ELECTRICAL CURRENT FLOW – circuit board with resistors to represent hydraulic conductivity and capacitors to represent storage coefficient – difficult to calibrate because each change of material properties involves removing and resoldering the resistors and capacitors Electrical Analog Model Hele Shaw Model (viscous liquid) Mathematical Model • MATHEMATICAL DESCRIPTION OF SYSTEM – SIMPLE – ANALYTICAL • provides a continuous solution over the model domain – COMPLEX - NUMERICAL • provides a discrete solution - i.e. values are calculated at only a few points • we are going to focus on numerical models Numerical Model Numerical Modeling • Formation of conceptual models • Manipulation of modeling software • Represent a site-specific ground-water system • The results are referred to as: – A model or – A model application Steps in a geohydrologic project 1. Define the problem 2. Conceptualize the system 3. Envision how the problem will affect your system 4. Try to find an analytical solution that will provide some insight to the problem 5. Evaluate if steady state conditions will be indicative of your problem (conservative/non-conservative) 6. Evaluate transients if necessary but always consider conditions at steady state Steps in a geohydrologic project 7. SIT BACK AND ASK - DOES THIS RESULT MAKE SENSE? 8. CONSIDER WHAT YOU MIGHT HAVE LEFT OUT ENTIRELY AND HOW THAT MIGHT AFFECT YOUR RESULT 9. Decide if you have solved the problem or if you need a. more field data b. a numerical model (time, cost, accuracy) c. both Steps in a geohydrologic project 9a. If field data are needed, use your analysis to guide data collection what data are needed? what location should they be collected from? Steps in a geohydrologic project 9b. If a numerical model is needed, select appropriate code and when setting up the model – – – – – keep the question to be addressed in mind keep the capabilities and limitations of the code in mind plan at least three times as much time as you think it will take draw the problem and overlay a grid on it note input values for • material properties, • boundary conditions, and • initial conditions – run steady-state first! – plan and conduct transient runs – always monitor results in detail Steps in a geohydrologic project 10.Keep the question in focus and the objective in mind 11.Evaluate Sensitivity 12.Evaluate Uncertainty Steps in a geohydrologic project KEEP THESE THOUGHTS IN MIND: 1. Numerical models are valuable thinking tools to help you understand the system. They are not solely for calculating an "answer". They are also useful in illustrating concepts to others. 2. A numerical modeling project is likely a major undertaking. 3. Capabilities of state-of-the-art models are often primitive compared to the analytical needs of current ground-water problems. 4. Data for model input is sparse therefore there is a lot of uncertainty in your results. Report reasonable ranges of answers rather than single values. 5. DO NOT get discouraged! 99% of modeling is getting the model set up and working. The predictive phase comprises only a small percentage of the total modeling effort. Components of Modeling Project • Statement of objectives • Data describing the physical system • Simplified conceptual representation of the system • Data processing and modeling software • Report with written and graphical presentations Steps in the Modeling Process • • • • • Modeling objectives Data gathering and organization Development of a conceptual model Numerical code selection Assignment of properties and boundary conditions • Calibration and sensitivity analysis • Model execution and interpretation of results • Reporting (K.J. Halford, 1991) Model Accuracy • Dependant of the level of understanding of the flow system • Requirements: – Some level of site investigation – Accurate conceptualization • Old quote: – “All models are wrong but some are useful” • Accuracy is always a trade-off between – resources and – goals Determination of Modeling Needs • What is the general type of problem to be solved? • What features must be simulated to answer the questions about the system?—study objective • Can the code simulate the hydrologic features of the site? • What dimensional capabilities are needed? • What is the best solution method? • What grid discretization is required for simulating hydrologic features? Modeling Code Administration • • • • • • Is there support for the code? Is there a user’s manual? What does it cost? Is the code proprietary? Are user references available? Is the code widely used? Types of Modeling Codes • Objective based: – Ground-water supply – Well field design • Process Based: – Saturated or unsaturated flow – Contaminate transport • Physical System Based • Mathematical Components of a Mathematical Model • Governing Equation (Darcy’s law + water balance eqn) with head (h) as the dependent variable • Boundary Conditions • Initial conditions (for transient problems) Solution Methods • In order of increasing complexity: – Analytical – Analytical Element – Numerical • Finite difference • Finite element • Each solves the governing equation of ground-water flow and storage • Different approaches, assumptions and applicability Analytical Methods • Classical mathematical methods • Resolve differential equations into exact solutions • Assume homogeneity • Limited to 1-D and some 2-D problems • Can provide rough approximations • Examples are the Theis or Theim equations Theis Equation Toth Problem Water Table Groundwater divide AQUIFER Groundwater divide Impermeable Rock Steady state system: inflow equals outflow Toth Problem Water Table Groundwater divide Laplace Equation Impermeable Rock 2D, steady state Groundwater divide Finite Difference Methods • Solves the partial differential equation • Approximates a solution at points in a square or rectangular grid • Can be 1-, 2-, or 3-Dimensional • Relatively easy to construct • Less flexibility, especially with boundary conditions Finite difference models may be solved using: • a computer program or code (e.g., a FORTRAN program) • a spreadsheet (e.g., EXCEL) Finite Difference Grid -- Simple Finite Difference Grid -Complex MODFLOW a computer code that solves a groundwater flow model using finite difference techniques Several versions available • MODFLOW 88 • MODFLOW 96 • MODFLOW 2000 • MODFLOW 2005 Finite Element Methods • • • • • Allows more precise calculations Flexible placement of nodes Good at defining irregular boundaries Labor intensive setup Might be necessary if the direction of anisotropy varies in the aquifer Structural features create anisotropy in this karst system Finite-Element Mesh for system Class Focus • Will use USGS finite-difference model, MODFLOW, for class presentations and exercises • More details on mathematics and simplifications used in MODFLOW later Governing Equations for Ground Water Flow Conditions and requirements: • Mass of water must be conserved at every point in the system • Rate and direction of flow is related to head by Darcy’s Law • Water and porous medium behave as compressible, elastic materials, so the volume of water “ stored” in the system can change as a function of head Governing Equations for Ground Water Flow • Many forms depending on the assumptions that are valid for the problem of interest. • In most cases, it is assumed that the density of ground water is spatially and temporally constant. Governing Equations for Ground Water Flow • Conservation of Mass Starting point for developing 3-D flow equation Mass In – Mass Out = Change in Mass Stored (If there is no change in storage, the condition is said to be steadystate. If the storage changes, the condition is said to be transient.) Small control volume over time in 3 directions -finite difference and differential forms -to be useful must be able to express flow rates and change in storage in terms of head (measurable variable) --- Darcy’s Law Governing Equations for Ground Water Flow • Darcy’s Law – 1856 experiment measured flow through sand pack – generalized relationship for flow in porous media Darcy’s Law • Relates direction and rate of ground-water flow to the distribution of head in the ground-water system where, Q = volumetric flow rate (discharge), A = flow area perpendicular to L (cross sectional area), K = hydraulic conductivity, L= flow path length (L = x1 - x0), and h = hydraulic head Darcy’s Law If the soil did not have uniform properties, then we would have to use the continuous form of the derivative: Darcy ' s Law: Q( x ) K ( x ) A dH dx Notice the minus sign on the right hand side of Darcy’s Law. We do this because in standard notation Q is positive in the same direction as increasing x, and we take x1 > x0. Notice that since H0 > H1, the slope of H(x), DH/Dx, is negative. If it had been the other way around, with H1 > H0, then the negative sign would ensure that Q would be flowing the other way. *** hydraulic head always decreases in the direction of flow *** From D.L. Baker online tutorial http://www.aquarien.com/sptutor/index.htm Head • Head is defined as the elevation to which ground water will rise in a cased well. Mathematically, head (h) is expressed by the following equation: • where • z = elevation head and P/pg = pressure head (water table = 0). Darcy’s Law Dupuit Simplification Dupuit's simplification uses the approximate gradient (difference in h over the distance x rather than the flow path length, l), and uses the average head to determine the height of the flow area. Mainly used for unconfined aquifers "Darcy tube" to flow in simple aquifers • LaPlace’s Equation: – Steady groundwater flow must satisfy not only Darcy's Law but also the equation of continuity – 3-Dimensional Steady State flow: Homogeneous, Isotropic Conditions where there are no changes in storage of fluid d2h/dx2+d2h/dy2+d2h/dz2=0 – Steady-state version of diffusion equation – the change of the slope of the head field is zero in the x direction – hydraulic head is a harmonic function, and has many analogs in other fields Assignment: • If you chose to purchase Applied Groundwater Modeling: – read the Preface and Chapters 1 and 2. • Begin thinking about class project • Begin looking at journal articles Pre- and Post- Processors • Many commercially available programs • Best allow placement of model grid over a base map • Allow numerical output to be viewed as contours, flow-path maps, etc • Some popular codes are: – – – – GMS (Ground Water Modeling System) Visual MODFLOW Groundwater Vistas MFI (USGS for setting up smaller models)