Life and Extremes

advertisement

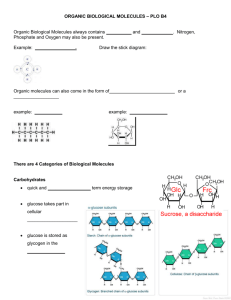

Life and Extremes Tori Hoehler NASA-Ames Research Center Seeks to Understand the Origins, Evolution, Distribution, and Destiny of Life in the Universe. Think Globally, Act Locally . . . In Astrobiology: Think as broadly as possible about our key questions (or risk missing something important) Be practical about where to look and what to look for (that’s the only way to design discerning missions) What is Life? Requirements and Limitations “Extremes” So what is life, anyway? Some Commonly Cited Attributes: Capable of reproducing itself (Can carry out chemical reactions and synthesis) (Can harness energy from the environment to drive these chemical processes) Capable of Darwinian evolution (mutation and natural selection) So what is life, anyway? Life According to Erwin Schrödinger (1944): Does Something Keeps on Doing Something (Longer than if it were Not Alive) The Factory Analogy for Life (cells are little factories that make more little factories) To build a new factory, we require: Raw Materials A Blueprint Energy & Work Tools & Machinery Blueprint, Machinery Doing anything with speed or specificity requires molecules that are very complex Big molecules required to store information Raw Materials (remember, we are talking about atomic materials) A basic building block that can be assembled into large, complex backbones Some interesting decorations to hang along the chain A way to connect the pieces together A lesson from Earth . . . Phosphorus & Nitrogen (backbone & decoration) Carbon (the backbone) Sulfur, Oxygen (interesting decorations) Hydrogen (filler/ H-bonds) These building blocks are connected together by chemical bonds Chemical bonds are made from electrons, of which life requires some source To do something, molecules need to interact This won’t happen (much) in the solid phase, because the molecules can’t come together across a significant distance. It could happen as a gas, but complex molecules are so big that they usually break down before they vaporize. So the molecules of life need to be dissolved in something. For Earth life, water is the solvent Energy Radiation Chemical Heat Mechanical (as visible light) Bottom Line Requirements for (our) Life Source of Energy Water Source of Carbon Nutrients Source of Electrons Microbiologists classify organisms based on how they fulfill these needs Life requires conditions that allow complex molecules to form and persist Possible Problems . . . Heat Radiation Strong Acid/Base Harsh Chemicals Any environment in which access to basic requirements is sketchy, or in which conditions threaten the stability of biomolecules, could be considered extreme Some extremes are absolute (universal to life), some are relative (specific to a particular kind of life) How can we define the limits for life? Use the only life we know – life on Earth – as a guide to understanding the prospects for, and how to seek, life elsewhere in the universe. How valid is the Earth-analog approach? It’s the best we’ve got, so far . . . Demands a focus on common traits, avoidance of highly specific circumstances If we seek to broadly define life's capabilities and limits, microbes are the place to look Genetic Diversity Metabolic Diversity Macroscopic World Aerobic (O2-based): Microbial World Light Inorganic Chemicals Organic Matter Plants Anaerobic: Light Inorganic Chemicals Organic Matter Animals Microbial Mat Tolerance of Extremes . . . Hydrothermal Vent (T = 115 ºC) (Photo: NOAA) Halite-Saturated Ponds, SF Bay (Photo: NASA) Acid Drainage (pH -0.7), Iron Mountain, CA (Photo: C. Alpers & D. Nordstrom, USGS) Some Yellowstone extremes High / Low Temperature High / Low pH Chemical Toxicity Desiccation / High Radiation (??) Back to the Big Picture . . . Understanding extremes on Earth, especially with the broad example of microbes, helps us to define “habitability”. In a theoretical sense, this tells us how common life could be. In a practical sense, it tells us where and how to focus a search for life on other worlds. Questions?