Parties, Party Systems, and Social Cleavages

advertisement

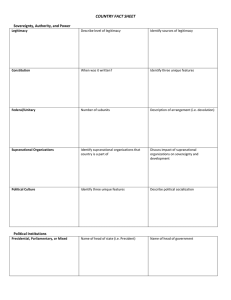

Why have political parties? What function do they play? Why do some countries have more parties than others? Why do some issues become salient in some countries (and at some times) but not others? Economics versus moral values? The rise of post-materialism, environmentalism? Return to Aristotle and our basic questions about redistribution and democracy: Why don’t the poor vote to expropriate the rich? Why parties? Cleavages in democracies since the 19th century The impact of social cleavages on party systems The role of electoral institutions Putting it all together A political party can be thought of as a group of people that includes those who hold office and those who help get and keep them there. Why do we need political parties to structure political life, even in non-democracies? Political parties serve several purposes: They structure the political world. Remember our discussion of social choice instability. In particular, they structure the legislative process. They recruit and socialize the political elite They mobilize the masses They provide a link between the rulers and the ruled. Political scientists often categorize democracies in terms of the type of party system that they exhibit. They typically distinguish between party systems based on the number and size of the parties they contain. A nonpartisan democracy is a democracy with no official political parties. A single-party system is one in which only one political party is legally allowed to hold power. A one-party dominant system is one in which multiple parties may legally operate but in which only one particular party has a realistic chance of gaining power. A two-party system is one in which only two major political parties have a realistic chance of gaining power. A multiparty system is one in which more than two parties have a realistic chance of gaining power. Effective Number of Parties It is a measure that weights the number of parties by the share of votes or seats they get. So a party that is large is counted more than a party that is very small. The idea is to down-weight the Monster Raving Loony Party, the Beer-Drinkers’ Party, etc. Among full democracies, the range is from the United States (around 2) to Brazil (18). A quick tour of social cleavages: Urban-rural cleavage Confessional cleavage Secular-clerical cleavage Class cleavage Post-materialist cleavage Ethnic and linguistic cleavages Regional cleavages Can we explain the number of parties by examining social cleavages? Can we explain the number of parties by examining social cleavages? Count the number of cleavages? Examine whether they are reinforcing or cross- cutting? What is a social cleavage anyway? Where do they come from? Primordialist vs. constructivist viewpoint Primordialists vs. constructivists Is ethnicity socially constructed? What about the class cleavage? A classic argument: The more social cleavages there are in a country and the more that these cleavages are cross-cutting, the greater the demand for distinctive representation and the greater the demand for political parties. Social cleavages create the demand for political parties. But electoral institutions determine whether this latent demand for representation actually leads to the existence of new parties. Specifically, non-proportional electoral systems act as a brake on the tendency for social cleavages to be translated into new parties. Mechanical effect Strategic effect Strategic voting Strategic entry The mechanical effect of electoral laws refers to the way votes are translated into seats. When electoral systems are disproportional, the mechanical effect: punishes small, geographically dispersed parties (Liberals) or large, geographically concentrated parties (Labor) Rewards large, geographically dispersed parties (Conservatives) and small, geographically concentrated parties (SNP, Bloc) The strategic effect of electoral laws refers to how the way in which votes are translated into seats influences the “strategic” behavior of voters and political elites. When electoral systems are disproportional, their mechanical effect can be expected to reward large parties and punish small parties. As a result, voters have an incentive to engage in strategic voting and political elites have an incentive to engage in strategic entry. The strategic voting essentially means voting for your most preferred candidate who has a realistic chance of winning. Strategic entry refers to the decision by political elites about whether to enter the political scene under the label of their most preferred party or under the label of their most preferred party that has a realistic chance of winning. Strategic Entry Game There are two left-wing parties (L1 and L2) and one rightwing party (R). If both left-wing parties compete in the election, then the right-wing party will win for sure. If only one left-wing party runs, then the right-wing party will lose. Strategic Entry Game The worst possible outcome for the left-wing parties is if the right-wing party wins (0). The best possible outcome for each left-wing party is if they win (1). The second best outcome for each left-wing party is if the other left-wing party wins (λ, where 0 < λ < 1). As you can see, both L1 and L2 face incentives for one of them to drop out of the race. They face incentives for strategic entry. But how do they coordinate on which one of them should drop out? The coordination game is asymmetric and therefore has distributional consequences. One way to solve this coordination problem is for the two small parties to merge into a single party. Example: The Liberal Party and the Social Democratic Party merged to creat the Liberal Democratic Party in the UK in 1988. The more disproportional the electoral system, the greater the incentive for small parties to merge or to form coalitions. This incentive not only encourages mergers between small parties but it can also deter the entry of small parties in the first place. What is it? How does it work? Why does India have so many parties? Why do different parties compete in different regions of Canada? Why are third parties so rare in the United States? There seems to be an emerging consensus in the literature about an interaction effect. Religion Immigration Environment, climate change? Functionalist arguments about social heterogeneity Colonial and historical legacies Strategic elites Boix Calvo Strategic fools?