Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the

advertisement

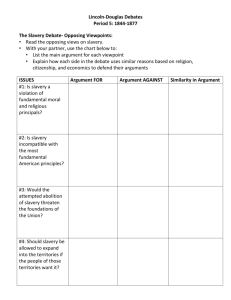

Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War … When I speak of the Republican ideology, therefore, I am dealing with the party's perception of what American society, both North and South, was like in the 1850s, and its view of what the nation's future ought to be… …The irrepressible conflict view is also weak when it centers on the moral issue of slavery, particularly in view of the distaste of the majority of northerners for the Negro and the widespread hostility toward abolitionists. Moral opposition to slavery was certainly one aspect of the Republican ideology, but by no means the only one, and to explain Republicans' actions on simple moral grounds is to miss the full richness of their ideology. And the revisionists can be criticized for denying altogether the urgency of the moral issue, and for drastically underestimating the social and economic differences and conflicts that divided North and South… …At the center of the Republican ideology was the notion of 'free labor.' This concept involved not merely an attitude toward work but a justification of ante-bellum northern society, and it led northern Republicans to an extensive critique of southern society, which appeared both different from and inferior to their own. Republicans believed in the existence of a conspiratorial 'Slave Power' which had seized control of the federal government and was attempting to pervert the Constitution for its own purposes. Two profoundly different and antagonistic civilizations, Republicans thus believed, had developed within the nation, and were competing for control of the political system… Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr; Morality, War, and Slavery …In view of this reticence on a point so crucial to the revisionist argument, it is necessary to reconstruct the possibilities that might lie in the back of revisionism. Clearly there could only be two "solutions" to the slavery problem: the preservation of slavery, or its abolition… If, then, revisionism has rested on the assumption that the nonviolent abolition of slavery was possible, such abolition could conceivably have come about thought internal reform in the South through economic exhaustion of the slavery system in the South, or through some government project for gradual and compensated emancipation. Let us examine these possibilities… 1) The internal reform arguments: the South, the revisionists have suggested, might have endued the slavery system if left to its own devices; only the abolitionists spoiled everything by letting loose a hysteria which caused the southern ranks to close in self-defense… …If revisionism has based itself on the conviction that things would have been different if only there had been no abolitionists, it has forgotten that abolitionism was as definite and irrevocable a factor in the historic situation as was slavery itself. And, just as abolitionism was inevitable, so too was the southern reaction against it; a reaction which--as Professor Clement Eaton has ably shown, steadily drove the free discussion--meant, of course, the extinction of any hope of abolition though internal reform… 2) The economic exhaustion argument. Slavery, it has been pointed out, was on the skids economically. It was overcapitalized and inefficient; it immobilized both capital and labor; its one-crop system was draining the soil of fertility; it stood in the way of industrialization. As the South came to realize these facts, a revisionist might argue, it would have moved to abolish slavery for its own economic good. As Craven put it, slavery "may have been almost ready to break down of its own weight." This argument assumed, of course, that Southerners would have recognized the cause of their economic predicament and taken the appropriate measures. Yet such an assumption would be plainly contrary to history and to experience. From the beginning the South has always blamed its economic shortcomings, not on its own economic ruling class and its own inefficient use of resources, but on Northern exploitation. Hard times in the eighteen-fifties produced in the South, not a reconsideration of the slavery system, but blasts against the North for the high prices of manufactured goods. The overcapitalization of slavery led, not to criticisms of the system but to increasingly insistent demands for the reopening of the slave trade. Advanced Southern writers like George Fitzhugh and James D. B. DeBow were even arguing that slavery was adaptable to industrialism. When Hinton R. Helper did advance, before the Civil War, an early version of Craven's argument, asserting that emancipation was necessary to save the Southern economy, the South burned his book. Nothing in the historical records suggests that the Southern ruling class was preparing to deviate from its traditional pattern of self-exculpation long enough to take such a drastic step as the abolition of slavery… J.G. Randall, The Blundering Generation …Traditional “explanation of the [Civil] [W]ar fail to make sense when fully analyzed. The war has been “explained” by the choice of a Republican president, by grievances, by sectional economics, by the cultural wish for Southern independence, by slavery or by events at Sumter. But these explinations crak when carefully examined. The election of Lincoln fell so far short of swinging Southern sentiment against the Union that secessionists were still unwilling to trust their case to an all-Southern convention or to cooperation among Southern States. . . Alexander H. Stephens stated that secessionists did not desire redress of grievances and would obstruct such redress. Prophets of sectional economics left many a Southerner unconivinced. . .The tariff was a potential future annoyance rather than an acute grievance in 1860. What existed then was largely a Southern tariff law. Practically all tariffs are one-sided. Sectional tariffs in other periods have existed without producing war. Such a thing as a Southern drive for independence on cultural lines is probably more of a modern thesis than a contemporary motive of sufficient force to have carried the South out of the Union on any broadly representative or all-Southern basis. . . It was hard for Southerners to accept the factory of a sectional party in 1860, but it was no part of the Republican program to smash slavery in the South, nor did the territorial aspect of slavery mean much politically beyond agitation. Southerners cared little about taking slaves into the territories; Republicans cared so little in the opposite sense that they avoided prohibiting slaver in territorial laws passed in February and March of 1861. . . Let one take all the factors traditionally presented – The Sumter maneuver, the election of Lincoln, abolitionism, slavery in Kansas, prewar objections to the Union, cultural and economic differences, etc. . . and it will be seen that only by a kind of flase display could any fo the issues, or all of them together be said to have caused the war if one omits the elements of emotional unreason and overbold leadership. If one word or phrase were selected to account for the war, that word would not be slavery, or economic grievance, or state rights, or diverse civilizations. It would have to be a word such as fanaticism (on both sides), misunderstanding, misrepresentation, or perhaps politics. . .