Boothroyd.X.JRP.writing.110103

advertisement

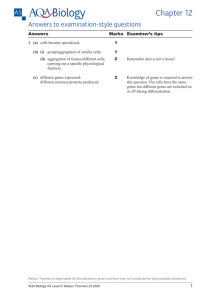

One person’s take on how to write a paper in the life sciences John Boothroyd, PhD Professor of Microbiology and Immunology With some edits and comments by John Pringle Professor of Genetics WHY publish? • Make your work public for the greater good (otherwise, why did you bother?) • Establish your reputation as a scientist • Establish your reputation as a responsible grantee who delivers value for the funds expended • It FEELS so good! What really matters • Accuracy of the data presented!! (Without this, nothing else matters much.) • Rigor and clarity with which the data are described and interpreted • Intellectual honesty in relating the work to the published literature • “A reputation takes years to build and seconds to lose…” Why write well? • If there has obviously been care expended in making the writing clear and mistake-free, there is a natural tendency to suppose that the research has been done with equal care. And vice versa! • Good writing makes your story easier to understand, which makes potential readers (1) more likely to read it, (2) more likely to understand it, and (3) less likely to be annoyed with you. (All of which are good!) Sad (or maybe not) but True • A mediocre thinker and/or experimentalist who writes very well is likely to have a successful independent career. • A brilliant thinker and/or experimentalist who writes poorly is unlikely to have a successful independent career (although s/he may do well as a student and postdoc). First steps • Begin the process way before the work is complete to identify “logic holes” AND so that the job is less daunting later • Decide on a tentative title to help crystallize what the paper is really about • Decide on target journal and look carefully at its format (print a paper) • Sketch out figures and tables (rough) • Decide on authors (with advisor and collaborators) Authors • ALL those who: – contributed data that are presented in the paper – or served an important, on-going intellectual role in the design and interpretation of the experiments • Not those who simply funded the work or offered a few helpful suggestions • Not those who just “need another publication” • Order is the responsibility of the senior author • Joint first and last authors possible • For Heaven’s sake, don’t be petty. (Remember, “A reputation takes years to build and seconds to lose…”) Title • Generally, succinct declaration of conclusions reached rather than methods used (unless basically a methods paper) • But … must be FOREVER an UNDENIABLY TRUE statement based on DATA SHOWN (and how many conclusions reach that point??) • OK to temper with “Evidence for…”, “Putative”, “Apparent”, “Role of…” if not iron-clad • Noun descriptor use sequence avoidance recommended (i.e., avoid using sequential nouns as adjectives) Titles Which would you prefer? • “Mapping effector genes by microarray analysis of human foreskin fibroblast cells infected with F1 progeny of a cross between two strains of the obligate intracellular Apicomplexan parasite Toxoplasma gondii.” OR • “Toxoplasma co-opts host gene expression by injection of a polymorphic kinase homologue.” Good Titles! • Campbell,…, Boothroyd (1984) Nature “Apparent discontinuous transcription of Trypanosoma brucei variant surface-antigen genes” • Sutton ad Boothroyd (1986) Cell “Evidence for trans-splicing in Trypanosomes” Abstract • Short and sweet • 1-2 sentences to set the stage [describe system; articulate what was unknown when began] • 1-2 sentences to say what was done • 2-3 sentences of what was observed • 1-2 sentences of conclusions reached • Usually no references (but depends on journal format) • No unexplained abbreviations • No unsubstantiated conclusions • Carefully choose key words for search discovery Example Abstract “The majority of known Toxoplasma gondii isolates from Europe and North America belong to three clonal lines that differ dramatically in their virulence, depending on the host [=intro]. To identify the responsible genes [=goal], we mapped virulence in F1 progeny derived from crosses between type II and type III strains, which we introduced into mice [=materials and methods]. Five virulence (VIR) loci were thus identified, and for two of these, genetic complementation showed that a predicted protein kinase (ROP18 and ROP16, respectively) is the key molecule [=results]. Both are hypervariable rhoptry proteins that are secreted into the host cell upon invasion [=more results]. These results suggest that secreted kinases unique to the Apicomplexa are crucial in the host-pathogen interaction [=conclusion].” Saeij et al., (2006) Science 314:1780-1783 Introduction • Big picture first • Describe current state of knowledge • Cite strategically, but be sure to include the competition’s (= potential reviewers’) work! • Don’t discuss or anticipate results • End with just two sentences summarizing what you did and what you found • Remember, you’re telling a story! Example End of Intro “To determine how different strains of Toxoplasma cause different disease, we mapped genes responsible for virulence in mice. We show that a family of polymorphic protein kinases are injected into a host cell during invasion and that these play a major role in strain-specific differences in virulence.” Grammar • Don’t use long strings of nouns – [“Toxoplasma-infected human foreskin fibroblast monolayers were incubated with…”] • Hyphenate nouns used to modify – [“Toxoplasma-infected cells”; “parasite-containing cells”; etc.] [But NOT “well established”] [Note: “we studied genes that control the cell cycle” and “we studied cell-cycle genes”.] • Learn to use punctuation well (it MATTERS!) • For example, commas go at natural pauses (as you would in speaking), including before conjunctions The genes, that control this response, were identified, without resorting to genetics. The genes that control this response were identified without resorting to genetics. Penguin press Materials and Methods • Goals: – enable others to repeat your experiments – enable the reader to understand what you did, especially around KEY details • Do NOT describe standard techniques that could be done many ways and wouldn’t alter the results – how you introduced a transgene probably isn’t important; exactly what you introduced is • So, DO describe crucial details of: – cloned genes (via primers is often easiest) – antibodies used (how raised or catalogue number and supplier) – all strain details – database versions, etc. Results Every paragraph is a mini-paper: • Introduction – background and context (why you’re doing it) • Materials and methods – what was done • Results – what was seen • Interpretation/conclusion – what it means (first-order conclusion) • First person OK but use sparingly and strategically: – Unnecessary: “We transfected the parasites with…”; preferred: “the parasites were transfected with…” – OK: “We favor…”, “We conclude”; i.e., wherever it’s a personal action Tips for Results • Begin the first or second sentence of most or even every paragraph with “To…” • Middle is, “The results (fig. 3) show…[literal description of what is seen]” • End with, “These results suggest that…” • Use past tense in describing what was done or observed, “To …., the parasites were transfected with…” • Use present tense in stating what we learn, “These results indicate that a mutation in xxx is responsible for …” OR conclusions that have been well vetted previously and are generally accepted in the field. “To…” examples Anderson, et al. (2009) Eukaryotic Cell 8:398-409 Tips for Results • Phrases to avoid: – “In order to…” Use “To…” – “Whether or not…” Just use “Whether…” – “Since…” [“Since the parasites were transfected with a Creexpressing plasmid…” – Use “As” or “Because” to avoid confusion about whether “since” refers to time or causality] – “The data was were used to…” • Hierarchy of strength for last sentences…: “The results prove/show/demonstrate > indicate > strongly suggest > argue for > suggest > support the notion > are consistent with > are not inconsistent with … General Tips • Make it flow • Say what you mean with the simplest words • Avoid jargon: e.g., “the gel was run”, “the oligonucleotide was kinased”, “the sequence was blasted against” • Avoid needless words (but don’t be shy about using the ones you need!) More Tips • Don’t use subjective adjectives without quantitation: – The mutants were much less virulent… – The mutants were much less virulent (xxxx had an LD50 20-fold higher than wild type)… • Avoid emotive adjectives: – Incredibly, amazingly, astonishingly similar… • But do key in reader to whether result is expected or not: – – – – – – Surprisingly, Interestingly, Importantly, Similarly, As expected, Consistent with the results described above, Figure Legends • Title should be declarative of experiment being presented or, if possible, (better) the point being made. • Then describe what was done and what is shown • Don’t discuss the results or give any interpretation (beyond what is in the title; i.e., NO “these results show…”) Figure Legends • EVERY detail of figure must be explained: – What do all symbols (e.g., arrows, boxing, hatching, triangles, etc.) represent? • Give only enough experimental detail to understand the essence of what was done: – don’t put in detail that could be in the materials and methods except where there is ambiguity • Use “Details as in Fig. 2” wherever truly identical Figures • Use big fonts so legible when reduced • Label intuitively so reader can understand without having to even read the figure legend • But still label each part “a”, “b”, etc. • Label gel lanes by description at top and by number at bottom Figures • Use arrows to highlight key aspects • Think about whether color really helps (often it doesn’t) – at some journals it is expensive! • Scale to journal column size, if poss. Discussion • Start with one or two sentence (ONLY) of overall recap, “The results presented here show that…” • Use to discuss second-order context of the work (what it all means, implications, etc.) • Do not go back over all the results, only discuss those that truly need further discussion Discussion (cont’d) • Share your wisdom with the reader but don’t abandon rigor or feed the dogma mill: – “The results strongly suggest… We cannot exclude the possibility, however, that …” • Let the data speak for themselves – avoid hyperbole and claims of “This is the first…” [save that for the cover letter!] Acknowledgements • Be inclusive (think hard about this) • Be generous (“cast your bread upon the waters”!) • Be careful about acknowledging grant/fellowship support • Can acknowledge grant support of a PI who is not an author (if, e.g., a post-doc is an author but that person’s PI is not because s/he was really not involved) Concluding Comments • Write at peak times and in solid chunks (remember just how important this is!) • Proof-read (and spell-check) before you pass it to anyone else. Twice, at least! • Have a lab-mate read and micro-edit it • Have someone outside your field read it • Enjoy telling a story and communicating the fruits of your labor And lastly… • Write assuming that ten years from now the most aggressive, obnoxious trial lawyer will wave your paper in your face and challenge you on every word of every sentence! Thanks to my group, who happily put up with my obsessive-compulsive editing!