The Inflation Enigma

advertisement

The Inflation Enigma

Part A: Price as a Relative Expression of Two Market Values

Part B: The Ratio Theory of the Price Level

Part II of The Enigma Series

Gervaise R.J. Heddle

December 2014

Abstract

• The Inflation Enigma is a two part paper focusing on the theory of

price determination (Part A focuses on microeconomics, Part B on

macroeconomics). In Part A, it is argued that price is a relative

expression of market value and every price is, in fact, a ratio of two

market values. By measuring market value in absolute terms, we can

think of price as being determined by two sets of supply and demand:

supply and demand for the good itself and supply and demand for the

measurement good (typically, money).

• In Part B, the microeconomic theory from Part A is used to develop the

“Ratio Theory of the Price Level”. Ratio Theory states that the price

level is a ratio of the “general value level” and the “market value of

money”. Ratio Theory is then used to develop two tools which will

help to explain the possible causes of inflation: the “Simple Model for

the Market Value of Money” and the “Goods-Money Framework”.

2

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

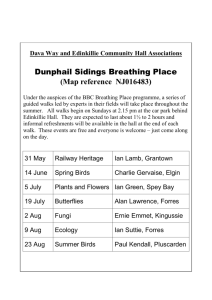

Index

Section

Slide

• Introduction & Overview

5

• Part A: Microeconomics

• Price Determination: An Introduction

55

• The Measurement of Value

105

• The Ratio of Exchange

• Supply & Demand in “Absolute Terms”

3

132

154

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Index

Section

Slide

• Part B: Macroeconomics

• Ratio Theory of the Price Level

183

• The Simple Model

• The Goods-Money Framework

234

• The Right Side of the Framework: Money

• The Left Side of the Framework: Goods

4

211

248

274

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Introduction & Overview

A Brief Overview of The Inflation Enigma

5

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Paradox of Price Level

Determination

• “Inflation” is nothing more than the evolution of prices over

time. Microeconomics tells us that the price of a good is

determined by supply and demand for that good. Clearly, this

principle can be easily extrapolated to the price of any number of

goods (the “basket of goods”). So surely, the evolution of the

general price level over time can not be that complicated: it is

simply a matter of changes in supply and demand for a wide

variety of goods? And yet, inflation remains an enigma.

• There is a good reason that macroeconomic models of price

determination (inflation) have limited success: it is because

current microeconomic models of price determination provide a

partial and one-sided view of the price determination process.

6

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Price of a Good is a

Ratio of Two Market Values

• The fundamental problem of most microeconomic theories of

price determination is that they fail to distinguish between

“price” and “market value”. The common view in economics is

that the price of a good is its “market value”: but the price of a

good is a relative expression of the market value of a good.

• The price of a good is a ratio of two market values. The price of a

good is determined by two sets of market forces: supply and

demand for the good itself, and supply and demand for the

“measurement good”. Supply and demand for a good can

determine its market value, but, in and of itself, it can’t determine

its price: its price depends upon on the market value of the good

itself and the market value of the other good being exchanged.

7

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Measurement of Market Value:

Absolute vs Relative

• Every good has the property of “market value”. The market

value of a good is determined by supply and demand for that

good. We can measure that market value in absolute terms (in

terms of a universal and invariable measure of market value) or

in relative terms (in terms of a variable measure of market value).

• Typically, we measure the market value of a good in relative

terms, that is, in terms of the market value of another good: this

is the “price” of the good. However, the price of the good can

only be determined if we know both the market value of the good

itself and the market value of the “measurement good”. In other

words, supply and demand for a good determines its market

value, but does not, in and of itself, determine its price.

8

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Price as a Ratio of

Two Quantities Exchanged

• In order to explain this concept, it helps to go back to basics. Let’s

answer the following question: what is the “price” of a good?

• In simple terms, “price” is a ratio of two quantities exchanged: a

quantity of one good as exchanged for a certain quantity of

another good. In mathematical terms, if we let the quantity of

good A be Q(A) and the quantity of good B be Q(B), then the price

of good A in terms of good B, denoted P(AB), is described by:

Q(B)

P(AB ) =

Q(A)

• As a general rule, we express prices in money terms. In the

equation above, good B would normally be “money”.

9

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Price as a Ratio of

Two Market Values

• How is this ratio of two quantities exchanged determined? Is the

ratio of exchange determined solely by supply and demand for

good A? Or is the ratio of exchange determined solely by supply

and demand for good B? The answer is neither. The price of

good A in B terms is determined by the market value of both

goods. In mathematical terms:

Q(B) V(A)

P(AB ) =

=

Q(A) V (B)

• The market value of good A, which we can measure in absolute

terms as V(A), is determined by supply and demand for good A.

Similarly, the market value of good B, denoted in absolute terms

as V(B), is determined by supply and demand for good B.

10

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Principle of Trade Equivalence

• In an efficient market, the ratio of two quantities exchanged (the

price of one good in terms of another) will always be the

reciprocal of the absolute market value of the two goods (the

market value of the goods as measured in absolute terms).

• Let’s assume you want to trade good A for good B. What

quantity of good B do you require in order to give up a certain

quantity of good A? It depends on the relative market value of

the two goods. Why? Because in a free and efficient market,

economic agents will only exchange goods if the total market

value of the two bundles of goods being exchanged are equal:

V(A)×Q(A) = V(B)×Q(B)

11

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Ratio of Quantities is the Reciprocal

of the Ratio of Market Values

• In simple terms, if good A is twice as valuable as good B (value

in this context is “market value”, ie. the value of the good as

determined by market forces), then for every unit of A you give

up, you would expect twice as many units of B in exchange.

V (A) Q(B)

=

V (B) Q(A)

• We know that the price of good A in terms of good B is, by

definition, equal to the second term in the equation above.

Therefore:

Q(B) V(A)

P(AB ) =

=

Q(A) V (B)

12

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

“Units of Economic Value”: An

Invariable Measure of Market Value

• In order to measure the market value of a good in absolute terms,

we need a universal and invariable measure of market value.

Classical economists spent a lot of time looking for a good that

possessed this quality (the labor theory of value), but there is no

good that possesses the quality of invariable market value.

• However, this doesn’t prevent us from creating a theoretical

measure of market value that is an invariable measure of market

value. For lack of a better term, we will call this invariable

measure “units of economic value”. Just as an “inch” is an

invariable measure of length, so a “unit of economic value” is an

invariable measure of market value. The market value of any

good can be measured in terms of “units of economic value”.

13

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Absolute vs Relative Market Value

• In our price equation, both the market value of good A, denoted

V(A), and the market value of good B, denoted V(B), are

measured in terms of “units of economic value”. We must

measure the market value of each good in the same terms in

order to be able to compare them.

Q(B) V(A)

P(AB ) =

=

Q(A) V (B)

• In this sense, we can say that V(A) represents the absolute market

value of good A (the market value of good A in terms of an

invariable unit of measure, “units of economic value”). In

contrast, P(AB) represents the relative market value of good A (the

market value of good A in terms of the market value of good B).

14

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Expressing Supply and Demand in

“Absolute” Market Value Terms

• The market value of a good is determined by supply and demand

for that good. Typically, supply and demand for a good is

expressed in terms of relative market value (price is on the y-axis).

In essence, it is assumed that the market value of the measurement

good (good B) is constant, allowing us illustrate how changes in

supply and demand for the primary good (good A) impact the

relative market value of good A, or P(AB ).

• However, by expressing the market value of both goods (A and B)

in “absolute” terms (in terms of a theoretical and invariable

measure of market value, “units of economic value”), we can

illustrate how changes in supply and demand for either good will

impact not only the absolute market value of each of the respective

goods but also the relative market value of the two goods.

15

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Supply and Demand in Terms of

Units of Economic Value

Supply and demand for good A determines the equilibrium market value of

good A, which is measured in terms of an invariable measure of market

value (“units of economic value” or “EV”) and denoted as V(A). Similarly,

supply and demand for good B determines the market value of good B, V(B).

Market Value

(EV)

Market Value

(EV)

“GOOD A”

“GOOD B”

S

S

V(B)

V(A)

D

D

Q(A)

Quantity

Q(B)

16

Quantity

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Using the Model to Determine

the Price of A in B Terms

We can use this simple framework to analyze the impact of changes in

supply and demand for either good upon the price of A in B terms. As

discussed, the price of A in B terms, or “P(AB )”, is equal to the ratio of V(A)

divided by V(B): if V(A) rises, the price rises, if V(B) rises, the price falls.

Market Value

(EV)

Market Value

(EV)

“GOOD A”

“GOOD B”

S

S

V (A)

P(AB ) =

V (B)

V(A)

V(B)

D

D

Q(A)

Quantity

Q(B)

17

Quantity

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

An Increase in Demand for Good A

Let’s analyze two scenarios. In the first scenario, there is an increase in

demand for good A (the demand curve for good A shifts to the right). An

increase in demand for A leads to higher market value for A. V(A) rises while

V(B) is constant and the price of A in B terms rises {P(AB ) = V(A)/V(B)}

Market Value

(EV)

Market Value

(EV)

“GOOD A”

“GOOD B”

S

S

V(A)1

V(B)

V(A)0

D1

D

D0

Q(A)0 Q(A)1 Quantity

Q(B)

18

Quantity

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

An Increase in Demand for Good A

in both EV and Price Terms

Our first scenario is easily demonstrated by traditional supply and demand

analysis. On the left hand side, market value is expressed in EV terms. On

the right hand side, market value is expressed in price terms (the price of A

in terms of good B): this is the “traditional” view.

Market Value

(EV)

Price

(in B terms)

“GOOD A”

“GOOD A”

S

S

V(A)1

P(AB)1

V(A)0

P(AB)0

D1

D0

D1

D0

Q(A)0 Q(A)1 Quantity

Q(A)0 Q(A)1 Quantity

19

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Why Did Traditional Analysis

Work for First Scenario?

• In this first scenario, traditional supply and demand analysis

provides the right answer. Why? Because traditional supply and

demand analysis assumes that the market value of the

measurement good (good B) is constant. In this scenario, it just

so happens that the market value of good B is constant, therefore

traditional supply and demand analysis gets the right result.

• But what happens when the market value of good B is not

constant? Traditional supply and demand analysis struggles to

explain changes in price due to a change in the market value of

the measurement good because its perspective is so “one-sided”.

However, we can use our alternative version of supply and

demand analysis to illustrate what happens.

20

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

An Increase in Demand for Good B

In our second scenario there is an increase in demand for good B (the

demand curve for good B shifts to the right). The equilibrium market value

of good B rises. The market value of good A is constant. Therefore, the price

of A in B terms, or “P(AB )”, falls: {P(AB ) = V(A)/V(B)}

Market Value

(EV)

Market Value

(EV)

“GOOD A”

“GOOD B”

S

S

V(B)1

V(A)

V(B)0

D

Q(A)

D1

D0

Q(B)0 Q(B)1

Quantity

21

Quantity

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Why Did the Price Fall?

• Let’s think about what just happened. There was no change in

the supply and demand for good A (as measured in “units of

economic value” terms) and yet the price of good A fell. Why

did the price fall? Because price is a relative expression of two

market values. All else equal, the price of good A as measured in

terms of good B will fall if the market value of good B rises:

V (A)

P(AB ) =

V (B)

• So, how can we represent this scenario in traditional supply and

demand format (with price on the y-axis)? If the market value of

the measurement good (good B) rises, then what happens to the

supply and demand curves for good A in B terms?

22

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Impact on Good A of an Increase in

Demand for Good B

In our second scenario there is an increase in demand for good B. The

equilibrium market value of good A is constant. However, the price of A in

B terms falls. Why? As the market value of good B rises, the supply and

demand curves for good A (as expressed in B terms) both shift lower.

Market Value

(EV)

Price

(in B terms)

“GOOD A”

“GOOD A”

S0

S

S1

P(AB)0

V(A)

P(AB)1

D0

D

Q(A)

D1

Quantity

Q(A)

23

Quantity

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Price Determination in a Barter

Economy (No Money)

• The principle that price is a ratio of two market values applies to

every price in the economy. In essence, the prices that we see

around us every day are the physical manifestation (the visible

portion) of a matrix of directly unobservable market values.

• We will use a number of examples to explore this concept. In our

first example, we will consider price determination in a two good

barter economy with no money. If the two goods in our economy

are apples and bananas, then what determines the apple price as

measured in banana terms (remember, there is no “money”)? Is it

supply and demand for apples or supply and demand for

bananas? The answer is both. The price of a good in terms of

another good depends on the market value of both goods.

24

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Foreign Exchange Rate

Determination

• We will also consider a more modern example: foreign exchange

rate determination. Every foreign exchange rate represents the

price of one currency in terms of another currency. Consider the

USD/EUR rate? Is this “price” determined by supply and

demand for US Dollars or supply and demand for Euros? Again,

the answer is both.

• Supply and demand for US Dollars determines the market value

of the US Dollar V(USD). Similarly, supply and demand for

Euros determines V(EUR). The USD/EUR exchange rate is then

equal to:

Q(USD) V(EUR)

P(EURUSD ) =

=

Q(EUR) V(USD)

25

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Money Price of Goods

• Ultimately, the point of these examples is to explain the general

principle that the price of one good in terms of another is

determined by the ratio of their market values. We can then

apply this principle to the determination of “money prices”.

• The money price of a good (the price of a good in terms of

money) is determined by the following ratio:

Q($) V (A)

P(A$ ) =

=

Q(A) V ($)

• Supply and demand for the good determines the market value of

the good V(A). Supply and demand for money determines the

market value of money V($) (not the interest rate!).

26

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Price of a Cup of Coffee

• In very simple terms, when you exchange a quantity of dollar

bills for a quantity of a good (say one cup of coffee), the idea is

that you are exchanging two “baskets” of equivalent total market

value.

V(Coffee)×Q(Coffee) = V($)×Q($)

• If the market value of one cup of coffee, as measured in absolute

terms, is three times that of the market value of one dollar bill,

then trade will only occur if you offer three dollar bills for that

cup of coffee. Therefore, the price of coffee, in dollar terms, is

equal to:

Q($) V (Cf )

P(Coffee$ ) =

=

=3

Q(Cf ) V ($)

27

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Supply and Demand for Money

• It is the view of The Enigma Series that supply and demand for

money, where “money” is defined as the monetary base (see The

Money Enigma), determines the market value of money. The

market value of money is the denominator of every money price

in the economy. Economics has struggled with this concept

because the market value of money is not directly observable (you

can’t observe market values in the absolute). The market value of

money can only be observed in a relative context, as a “price” (a

fact that is true of all market values).

• Supply and demand for money does not determine “the interest

rate”, although the manner in which newly created money is

used (to buy government debt) does influence the interest rate.

28

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Every Money Price is Determined by

Two Sets of Supply and Demand

We can use our theory to visualize the determination of “money prices”.

Supply & demand for good A determines the market value of good A, V(A).

Supply & demand for money determines the market value of money, V($).

The money price of good A is equal to the ratio of the two market values.

Market Value

(EV)

V(A)

Market Value

(EV)

“GOOD A”

S

V (A)

P(A$ ) =

V ($)

“MONEY”

Supply

V($)

Demand

D

Q(A) Quantity

Q($) Base Money

29

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Towards a Model of Inflation

• The second part of The Inflation Enigma (Part B) focuses on

extending the microeconomic theory developed in the first part

(Part A) and building macroeconomic tools that can be used to

explain the nature of price level determination.

• While the notion that price is a relative expression of two market

values is a useful tool in a microeconomic context, it is

fundamental in a macroeconomic context. It is the view of this

paper that a comprehensive theory of inflation must build upon

the principle that every money price in the economy is a function

of two market values. More specifically, supply and demand for

money determines the market value of money which, in turn, is

the denominator of every money price in the economy.

30

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Ratio Theory of the Price Level

• Part B of this paper begins by deriving the “Ratio Theory of the

Price Level”. Ratio Theory states that the general price level p

can be expressed as a ratio of two market values:

Where

VG

p=

VM

p is the general price level of the economy

VG is the “general value level” of the economy

VM is the absolute market value of money

• The general value level VG is a hypothetical measure of overall

market values (as measured in “units of economic value”) for the

set of goods and services that comprise the “basket of goods”.

31

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Ratio Theory as a Starting Point

for Our Analysis of Inflation

• In essence, Ratio Theory states that a rise in the price level can be

due to either (i) a rise in the overall absolute market value of

goods VG or (ii) a fall in the absolute market value of money VM .

This theory has many implications and can be used to highlight

the overly simplistic nature of the typical “inflation vs deflation”

debate. For example, the common view that a decline in

aggregate demand “must be deflationary” completely ignores the

role of the market value of money.

• It should be noted that Ratio Theory is not a theory of inflation

per se, but rather a starting point for analysis. In order to make

Ratio Theory “useful” we need to understand the principle

factors that drive each of the two key variables (VG and VM ).

32

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Price Level Determination:

Long Run vs Short Run

• In order to simplify the analysis of price level determination, The

Inflation Enigma separates the analysis into two buckets: price

level determination in the long run and price level determination

in the short run.

• Ultimately, the long run determination of prices is just an

aggregated path of short run processes. It would be preferable not

to distinguish between the long run and short run because the

fundamental price level determination process is the same in both

cases. However, in order to fully understand the short run

process, we need to develop a more comprehensive model of the

price level. This more comprehensive model is constructed in the

last paper in the series, The Velocity Enigma.

33

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Price Level Determination

in the Long Run

• When measured over very long periods of time, changes in the price

level are strongly correlated to changes in the ratio of base money to

real output. This is the long run application of the quantity theory of

money, an economic phenomenon for which there is strong

empirical support (King, 2001).

• The reason quantity theory works in the long run, but not in the

short run, is because money is a long-duration, special-form equity

instrument. In the short run, the value of a long-duration equity

instrument is highly sensitive to shifts in expectations. However,

when measured from point to point over long periods of time, most

of the change in the value of such an instrument is determined by

the historic change in the output/base money ratio (the

earnings/share ratio), not shifts in future expectations.

34

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Value of a Long-Duration Asset:

Long Term versus Short Term

• We can highlight this point by think about the pricing of a longduration, proportional claim: common stock. Imagine a stock with

a P/E ratio of 20 and earnings of $1 per share. Over the next two

years, earnings rise to $1.25 per share, but the P/E ratio falls to 16

(lower growth expectations). Over the next eighteen years, earnings

rise to $10 per share while the P/E ratio remains at 16.

• Over the first two years, the stock price performance seems to have

nothing to do with EPS: EPS rises 25% ($1 to $1.25) but the share

price doesn’t change (stays at $20). But measured over the entire

twenty year period, the share price does track earnings per share, at

least roughly: the stock price rises 8x (to $160) while EPS is up 10x.

Over long periods of time, changes in EPS tend to overwhelm

changes in expectations (which are reflected in the P/E multiple).

35

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

A Simplified Analysis of the

Market Value of Money

• In the short term, the value of money may seem to have nothing to

do with the output/money ratio. However, when measured over

long periods of time, the market value of money is driven primarily

by the ratio of real output to base money. Proportional claim

theory states that money represents a variable entitlement to the

output of society. If we can ignore or minimize the impact of

changing expectations (which we can if discussing changes over

very long periods of time), then we should expect that the market

value of a proportional claim to the output of society should rise as

real output rises and falls as the monetary base increases.

• These notions can be further illustrated by merging Ratio Theory

with the quantity theory of money to create the Simple Model for

the Market Value of Money (see next slide).

36

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Simple Model for the

Market Value of Money

• Ratio Theory and the Equation of Exchange are used to derive

the “Simple Model for the Market Value of Money”:

VG × q

VM =

M ×v

• The Simple Model states that the absolute market value of

money VM can be expressed as a function of four variables:

1. The general value level VG , a hypothetical measure of overall

absolute market values for the “basket of goods”;

2. Real output q;

3. The monetary base M; and

4. The velocity of base money v.

37

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Basic Implications of

The Simple Model

• The Simple Model provides further, albeit very limited, insight

into the market value of money. All else equal, the absolute

market value of money is positively related to both the general

value level and real output. As expected, the market value of

money is negatively related to the number of claims issued, the

monetary base: as the number of outstanding claims increases,

the proportional entitlement of each claim falls.

• In the long run, if the velocity of money is relatively stable, then

the market value of money is primarily determined by the ratio

of real output to the money base. Since the value of money is

the denominator in the price level, the price level is primarily

determined by the ratio of money base to real output.

38

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Price Level Determination

in the Short Run

• One of the primary implications of the Simple Model is that, in

the long run, the general value level VG is irrelevant to the

determination of the price level. Why? Because any rise or fall in

the value of goods VG is reflected in the value of money VM .

(With velocity stable, a rise in VG leads to a rise in VM and there is

no change in the price level which is a ratio of the two). Longterm, only real output and base money matter.

• However, in the short run, changes in the general value level are

not automatically reflected in the market value of money. Money

is a long-duration asset and it will often “look through” what are

perceived to be temporary adjustments in the general value level.

Therefore, we need a model to analyze both variables.

39

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

A Two-Market Model for

Price Level Analysis

• In order to help us analyze short-term movements in the price

level, we will introduce a basic two-market model called “The

Goods-Money Framework”.

• The Goods-Money Framework proposes that (1) the equilibrium

general value level VG is determined by aggregate demand and

aggregate supply in the market for goods/services and (2) the

equilibrium absolute market value of money VM is determined

by supply and demand for the monetary base. The key

implication of the Goods-Money Framework is that the price

level is determined, in a stylized sense, by two sets of supply and

demand, it is not determined solely by aggregate supply and

demand as represented in traditional Keynesian analysis.

40

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Goods-Money Framework

Aggregate supply and demand for goods/services determines the

equilibrium general value level VG and real output q. Supply and

demand for money determines the market value of money VM .

“LEFT SIDE: GOODS”

“RIGHT SIDE: MONEY”

General Value Level (EV)

Value of Money (EV)

AS

Supply

VG

p=

VM

VG

VM

Demand

AD

q

Real Output

M

41

Base Money

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Left Side of the Framework

• The Left Side of the

Framework is a short run

model of aggregate demand

and aggregate supply, where

both functions are expressed

in terms of the general value

level and real output.

LEFT SIDE OF

THE FRAMEWORK

General

Value

Level

(EV)

“GOODS/SERVICES”

Aggregate

Supply

VG

q

• The intersection of

aggregate demand and

aggregate supply determines

Aggregate

equilibrium levels of real

Demand

output and the general value

level.

Real Output

42

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Right Side of the Framework

• The Right Side of the

Framework is the market for

money. The supply of money

(the monetary base) is fixed.

Demand for money is plotted

in terms of the absolute

market value of money.

THE RIGHT SIDE OF

THE FRAMEWORK

“MONEY”

Value of

Money (EV)

• The intersection of supply

and demand for money

determines, in the first

instance, the equilibrium

absolute market value of

money.

Supply

VM

Demand

fn{VG ,q, v}

M

43

Base Money

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Example One: Increase in

Aggregate Demand

• Let’s briefly consider two

basic examples. In this

example, the aggregate

demand curve shifts to the

right. Equilibrium levels of

real output q and the general

value level VG both rise.

LEFT SIDE OF

THE FRAMEWORK

General

Value

Level

(EV)

“GOODS/SERVICES”

Aggregate

Supply

VG,2

VG,1

• All else equal, the rise in VG

will lead to a rise in the price

level:

AD2

AD1

q1 q2

Real Output

44

VG

p=

VM

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Example Two: Increase in

Demand For Money

• In this second example, there

is an increase in the demand

for money. The demand

curve for money moves to

the right. The equilibrium

absolute market value of

money VM rises.

THE RIGHT SIDE OF

THE FRAMEWORK

“MONEY”

Value of

Money (EV)

Supply

VM,2

• All else equal, the rise in VM

will lead to a fall in the price

level:

VM,1

VG

p=

VM

D2

D1

M

45

Base Money

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Interpreting the Goods-Money

Framework

• Superficially, the implications of the Goods-Money Framework

may seem obvious. A basic reading would suggest that excess

aggregate demand always leads to a rise in the value of goods VG

and the price level, or that an increase in base money always leads

to a fall in the value of money VM and a rise in the price level.

Unfortunately, it is just not that simple.

• The main problem with this simple analysis is twofold. Firstly, a

change in the left side of the framework may (or may not) impact

the value of money VM . If VG and q both rise, then this may or

may not lead to an increase in the value of money depending

upon whether the shift in the value of goods and real output is

perceived to be temporary or permanent.

46

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Reaction to a Perceived “Temporary”

Increase in Aggregate Demand

Aggregate demand rises, but the rise is perceived to be temporary.

Output and general value level rise. Money is a long-duration asset:

there is no change in long-term expectations and hence negligible

change in VM . The end result is the price level rises (p = VG /VM ).

General Value Level

Value of Money

AS

Supply

VG,1

VM

VG,0

AD0

q0 q1

“No Change”

AD1

Real Output

47

D0 = D1

M

Base Money

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

What Happens to the Value of

the Financial Instrument?

• In the scenario on the previous page, an increase in aggregate

demand that is perceived to be temporary has no impact on the

value of money. Why? Because money is a long-duration

financial instrument. The value of long-duration equity

instrument is determined primarily by expectations regarding the

distant future. If those expectations are largely constant, then the

value of money doesn’t change.

• The net result in this scenario is that the price level rises and the

velocity of money rises. However, if the increase in both the

general value level and real output was perceived to be more

permanent in nature, then this should lead to a rise in the value

of money, which could offset the rise in the value of goods.

48

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Reaction to a Perceived “Permanent”

Increase in Aggregate Demand

Aggregate demand rises and the rise is perceived to be more “permanent” in

nature. The value of money rises as it discounts the higher future levels of

output (VG q) that will be claimed by each unit of money. The end result is

little change in the price level: the rise in VG is offset by the rise in VM.

General Value Level

Value of Money

Supply

AS

VG,1

VM,1

VG,0

VM,0

AD0

q0 q1

AD1

Real Output

49

D0

M

D1

Base Money

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Market for Money: Supply and

Demand a “Second Best” Tool

• The second major problem with a superficial interpretation of

the Goods-Money Framework is that it suggests that the value of

money will fall if the money supply curve shifts to the right (the

monetary base increases). Again, it isn’t that simple. Supply and

demand analysis is a “second best” solution for analyzing the

market for money. The better model for analyzing the market

value of money is the discounted future benefits model

developed in The Velocity Enigma.

• Money is a long-duration financial instrument. An increase in

the monetary base may have little or no impact on the value of

money if that increase is perceived to be temporary. What

matters are long-term expectations of the output/money ratio.

50

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Right Side of the Framework

• An entire section of this paper is devoted to discussing the Right

Side of the Goods-Money Framework (the market for money). In

particular, we begin to discuss the practical implications of the

notion that money is a long-duration financial instrument.

Namely, that in the short term, the market value of money is

highly sensitive to changing expectations regarding the long-term

path of important economic variables (most notably, real output

and money).

• Unfortunately, we can only scratch the surface of these issues in

this paper. In order to fully understand the determination of the

market value of money, we need the “Discounted Future

Benefits Model” that is developed in The Velocity Enigma.

51

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

“Sticky Wages” Explained by

Rational Expectations

• The last section of the paper discusses the derivation of the Left

Side of the Goods-Money Framework. In particular, it focuses

on the derivation of the aggregate demand and aggregate supply

functions as expressed in terms of the general value level and

contrasts this model with the traditional AD/AS model.

• It is argued that the slope of both functions is largely due to

expectations of cyclicality and mean reversion in the general

value level (a property that is not present in the price level). It

will be argued that these expectations of mean reversion in the

general value level can also be used to explain why wages are (or

at least appear to be) “sticky” in an efficient market with no

nominal rigidities.

52

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

A Preview of

The Velocity Enigma

• The Inflation Enigma should be considered as an introduction to

the issues involved in the determination of the price level. We

will use the tools developed in this paper (Ratio Theory, the

Simple Model and the Goods-Money Framework) in the final

paper in the series, The Velocity Enigma.

• The Velocity Enigma combines the issues discussed in The

Money Enigma (the nature of money) with the issues discussed

in The Inflation Enigma (the basic nature of price level

determination) to develop a much more comprehensive,

expectations-based model of the price level. The Velocity Enigma

concludes by comparing this model with the views of the major

schools of economic thought.

53

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Part A:

Microeconomic

Price Determination

54

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Price Determination:

An Introduction

Price as a Ratio of the Market Value of Two Goods

55

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Microeconomic Price Determination:

An Introduction

• Most people are confident that they understand why the dollar

price of a good goes up or down: “supply and demand”. But

what determines the dollar price of a good isn’t as simple as just

supply and demand for the good itself. That isn’t to say that

supply and demand for that good isn’t important, but it’s only half

the picture. Supply and demand for a good determines its “market

value”, but every price is a ratio of two market values.

• The other half of the picture is the market value of money as

determined by supply and demand for money. The market value

of money is the critical denominator of every “money price” and

is just as important in determining the price of a good as the

supply and demand for that good.

56

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Price is an Expression of

Relative, not Absolute, Market Value

• Every price is a ratio of two quantities exchanged: a quantity of

one good for a quantity of another. It is the contention of this

paper that this ratio is determined by the relative market value of

the two goods being exchanged.

• Trade, at its simplest level, is nothing but the exchange of two

baskets, one for another. A trade could be one apple for one pear,

or it could be one apple for two dollars. Either way, the ratio of

exchange (pears for apples, dollar for apples) depends on the

market value of both items being exchanged. This “ratio of

exchange” is commonly referred to as the “price” of the

transaction. The ratio of two quantities exchanged (price) can not

be determined by the market value of just one of those goods.

57

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Property of Market Value

• In order to understand this concept, we need to think about the

property of “market value”. A good must possess the property of

market value for it to have any value in exchange. The market

value of a good is separate and distinct from its “non-market

value”, more commonly known as its “utility”. The two concepts

are related, but they are fundamentally different.

• The problem with “value”, whether it be “market value” or “nonmarket value” is that it is a very difficult property to measure. In

the case of utility (non-market value), economics has created a

theoretical and invariable unit of non-market value called the

“util”. The “util” is an absolute measure of the non-market value

of a good, just as “inches” are an absolute measure of length.

58

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Measuring Market Value

• In contrast, economics has not developed an widely accepted

measure of the absolute market value of a good. Instead,

economic theories of price determination rely solely on the

measurement of market value in relative terms.

• Almost universally, market value is measured on a relative basis:

the market value of a good is measured with reference to the

market value of another good. This method of measuring

market value produces a ratio of two quantities exchange, or a

“price”. This practice is so common that most people equate the

“market value” of a good with its “price”. But technically, the

price of a good in terms of another good is only one possible

expression of that good’s market value.

59

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Height vs Relative Height

• We can simplify our discussion by comparing the concept of

“market value” with a simple physical property with which we

are all familiar: “height”.

• Most of the physical objects we see around us possess the

property of height. We can measure height in two basic ways. We

can measure the height of an object in absolute terms (in terms of

an invariable unit of height such as feet or inches) or we can

measure the height of an object in relative terms (the tree is three

times taller than the girl). Both are acceptable ways to measure

the property of height. However, in order for us to able to

compare the height of two objects on a relative basis, both objects

must possess the property of height in the absolute sense.

60

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Any Property Compared on a Relative

Basis, Must Exist in the Absolute

• In economics, common practice is to express the market value of

a good in terms of another good. For example, the market value

of an apple is three dollars. In effect, this is the same as saying

that the height of the tree is three girls.

• However, if it is possible for us to express the market value of a

good in terms of another good, it must be true that both goods

have market value and that we can, at theoretically, measure the

market value of each good in terms of an invariable unit of

market value. Just as we can measure the height of a tree in

terms of feet and/or inches, so we can measure the market value

of the apple in terms of a universal and invariable measure of

market value. All we need to do is create one.

61

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

“Units of Economic Value”

An Invariable Measure of Market Value

• Classical economists such as Adam Smith and David Ricardo

spent a lot of time looking for a good that could, in effect, act as

an invariable measure of market value. (The labor theory of

value suggested labor is that invariable measure).

• In reality, no good has the property of invariable market value.

However, this does not prevent us from creating a theoretical

measure of market value that is universal and invariable. So, let’s

create a universal measure of market value and let’s call it a

“unit of economic value” or “EV”. Units of economic value are

an invariable measure of the market value of a good. Just as

height can be measured in feet and/or inches, the market value

of any good can be measured in terms of units of economic

value.

62

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Price as a Ratio of

Quantities Exchanged

• Once we have created an invariable measure of the market value

(“units of economic value”), the task of understanding price

determination becomes much easier.

• Let’s start with the general case. Assume we have two goods:

apples (good “A”) and bananas (good “B”). We want to

determine the price of apples in banana terms. We know that

price is a ratio of two quantities exchanged: a quantity of B,

denoted Q(B), for a given quantity of A, Q(A). Mathematically,

the price of A in B terms, denoted P(AB ), can be stated as:

Q(B)

P(AB ) =

Q(A)

63

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Principle of Trade Equivalence

• So, how is this ratio of quantities exchanged determined? We

need to start with one basic principle that we shall call “the

principle of trade equivalence”.

• The principle of trade equivalence is the simple notion that, in an

efficient market, two parties will never exchange baskets of goods

unless those baskets are of equivalent total market value. If we

denote the market value of apples in EV terms (“units of

economic value”) as V(A) and the market value of bananas in EV

terms as V(B), then the principle of trade equivalence states that

trade will only occur if:

V(A)×Q(A) = V(B)×Q(B)

64

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Reciprocal Relation Between

Quantities and Market Value

• Let’s rearrange the formula on the previous slide and discuss

what in means in practical terms:

Q(B) V (A)

=

Q(A) V (B)

• What determines the ratio of exchange in our example? How

many many bananas must you receive in order to give up one of

your apples? In essence, the principle of trade equivalence states

that it depends on both the market value of apples V(A) and the

market value of bananas V(B). If an apple is three times more

valuable than a banana {V(A) = 3V(B)}, then someone must offer

you three bananas for you to give up one apple.

65

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Price is a Ratio of

Two Absolute Market Values

• As stated earlier, the price of good A in good B terms, denoted

P(AB ), is equal to the ratio of two quantities exchanged. The

principle of trade equivalence implies that this ratio of two

quantities exchanged is equal to the reciprocal of the ratio of the

absolute market value of the two goods. Therefore, the price of

good A in terms of good B is equal to:

Q(B) V(A)

P(AB ) =

=

Q(A) V (B)

• The price of one good in terms of another is determined by a

ratio of two market values (the absolute market value of the

primary good, good A, divided by the absolute market value of

the measurement good, good B).

66

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Money Price of Goods

• So far, we have discussed the principle of price determination in

general terms: the price of one good in terms of another is

determined by the ratio of their absolute market values. Now, we

can apply this principle to the determination of “money prices”.

• The money price of a good (the price of a good in terms of

money) is simply the ratio of the number of units of money

(dollars) that must be exchanged in return for one unit of a good

(good A). Therefore, the price of good A in dollar terms is equal

to the quantity of dollars exchanged, Q($), for a certain quantity

of good A, Q(A).

Q($)

P(A$ ) =

Q(A)

67

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Market Value of Money

• Why is it possible to exchange good A for money? Because both

good A and money possess the property of “market value”. As

discussed in The Money Enigma, money can only act as a

medium of exchange because it has value (derived from its status

as a financial instrument). More specifically, money possesses

the property of market value and we can, at least theoretically,

measure this market value in terms of a universal and invariable

unit of market value (“units of economic value”).

• It is the relative relation between the market value of money and

the market value of a good that determines the price of a good in

money terms. We can see this by applying the principle of trade

equivalence to a money-based transaction.

68

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Principle of Trade Equivalence Applied

to a Money-Based Transaction

• Money is accepted in exchange for goods because money has the

property of market value. We can measure the market value of

money in terms of units of economic value: this is the absolute

market value of money, denoted V($).

• In an efficient market, a money-based transaction will only occur

when the total market value of the basket of good A exchanged

is equal to the total market value of the basket of money

exchanged:

V(A)×Q(A) = V($)×Q($)

• In simple terms, in an efficient market, trade only occurs when

two parties swap baskets of equal market value. In most

transactions, one of those baskets contains a quantity of money.

69

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Price in Dollar Terms is a

Ratio of Two Market Values

• Rearranging the previous equation, the ratio of the quantity of

dollars exchanged and the quantity of good A exchanged is

determined by the relative market value of the two goods:

Q($) V (A)

=

Q(A) V ($)

• As we know, the price of good A in dollar terms is equal to this

ratio of quantities exchanged. Therefore, the price of good A in

dollar terms is a ratio of two market values:

Q($) V (A)

P(A$ ) =

=

Q(A) V ($)

70

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

What Determines Market Value?

Supply and Demand

• If price is determined by a ratio of two market values, then what

determines market value? Economics already has a well established

paradigm for answering this question: supply and demand. Supply

and demand determines market value: we can measure market value

in absolute terms or, as is common practice, in relative terms.

• If supply and demand determines the market value of a good where

that market value is measured in relative terms (in terms of another

good), then supply and demand must also determine the market

value of that good where the market value is measured in absolute

terms (in terms of an invariable unit of measure). Put another way, if

supply and demand does not determine market value as measured in

absolute terms, then it doesn’t determine market value as measured

in relative terms (in terms of “price”).

71

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Market for Apples in

“Units of Economic Value” Terms

• Supply and demand for apples

determines the market value of

apples. In this case, the market

value of apples is measured in

absolute terms V(A).

Supply

THE MARKET FOR APPLES

Market value in

“EV” terms

V(A)

Q(A)

• The supply and demand curves

for apples are both expressed in

terms of units of economic value,

an invariable measure of market

value. The intersection of supply

Demand

and demand determines the

equilibrium market value of

Quantity

apples V(A).

72

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Two Ways to Illustrate Exactly

The Same Thing

The two diagrams below are identical in every aspect except one: the unit of

measurement. In the first, supply and demand are represented in terms of an

invariable unit of market value. In the second, the schedules are represented

in terms of a good (dollars), the market value of which is assumed constant.

Market Value

(Units of EV)

“APPLES”

Market Value

(Dollars)

“APPLES”

S

S

V(A)

P(A$ )

D

D

Q(A)

Quantity

Q(A)

73

Quantity

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Every Price is Determined by

Two Sets of Supply and Demand

• If the price of a good is determined by the relative market value of

two goods and the market value of a good is determined by

“supply and demand”, then it follows that the price of a good is

determined by two sets of supply and demand.

• The traditional representation of supply and demand for a good

in price terms provides a rather simplified and somewhat

misleading view of the price determination process. If there is

little or no movement in the unit of measurement (the currency),

then changes in the price of the good will primarily reflect

changes in supply and demand for that good. However, if the

market value of the unit of measurement (money) is not

constant, then we have a problem.

74

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Problem with Traditional

Demand & Supply Analysis

• The issue can be illustrated by considering the determination of

prices in a barter economy with no money. Imagine an economy

with two goods (apples and bananas) and no currency. What is

the price of apples and how is that price determined?

• There is only one meaningful way to express the price of apples

in our two good economy: in terms of bananas. For example, an

apple might cost two bananas. If there is more demand for

apples, then the price of apples might rise to three bananas. If the

demand for apples falls, then the price might fall to one banana.

The traditional demand/supply framework works fine so far. But

what happens to the price of apples (in banana terms) if there is

an increase in the demand for bananas?

75

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Price of Apples

• If there is an increase in the demand for bananas, then (all else

equal) the price of apples in banana terms will fall. But how is

that possible with “no change” in supply and demand for apples?

• Consider this question: What determines the price of apples as

expressed in banana terms? Is it supply and demand for apples?

Or is it supply and demand for bananas?

• The answer is simple: both. The price of apples, in banana terms,

depends on both the supply and demand for apples and the

supply and demand for bananas. If there is a sudden increase in

demand for bananas, the value of an banana rises and, all else

equal, the number of bananas required to purchase an apple falls.

76

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Blind Spot: The Market Value

of the Measurement Good

DEMAND & SUPPLY

FOR APPLES

Price of apples in

“banana terms”

P(AB)

Q(A)

• This traditional supply and

demand diagram for apples

focuses on changes in supply and

demand for apples and the

impact on the price of apples.

Supply

• But what happens if there is a

change in the supply and demand

for bananas? The problem is that

this representation of the

“market for apples” assumes that

Demand

there is no change in the market

value of bananas (the

Quantity

“measurement good”).

77

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Is There a Solution?

• How can we illustrate the impact of a change in supply and

demand for bananas on the price of apples. [Remember, there is

no money in our economy: we can’t just express the price of both

goods in money terms and then calculate the price of apples in

banana terms by dividing the two money prices.] What we need

is a way to illustrate how the price of apples (in banana terms)

changes in response to changes in both the supply and demand

for apples and the supply and demand for bananas.

• The solution is quite simple (although a little abstract): we use

our independent unit of measurement of market value, “units of

economic value”, to express supply and demand for each good in

terms of absolute measure of market value.

78

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Two Markets: Apples & Bananas

The price of apples (in banana terms) is determined by both supply and

demand for apples and supply and demand for bananas. We can represent

this by expressing both sets of supply and demand schedules in terms of an

invariable measure of market value, “units of economic value”.

Market Value

(Units of EV)

“APPLES”

Market Value

(Units of EV)

“BANANAS”

S

S

V (A)

P(AB ) =

V (B)

V(A)

V(B)

D

D

Q(A)

Quantity

Q(B)

79

Quantity

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Calculating the Price of Apples

in Banana Terms

• It is the contention of this paper that supply and demand for

apples determines, in the first instance, the market value of

apples, not the “price” of apples. Similarly, supply and demand

for bananas determines, in the first instance, the market value of

bananas. In both cases, we can measure market value in

“absolute terms”: in terms of an invariable unit of market value.

• As discussed, the price of apples, in banana terms, is then a ratio

of these two absolute market values. More specifically, the price

of apples in banana terms P(AB ) can be calculated as:

V (A)

P(AB ) =

V (B)

80

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

An Increase in Demand for

Bananas….

We can now use our model to illustrate the impact of an increase in the

demand for bananas on the “apple price”. The demand curve for bananas

shifts from D0 to D1. The absolute market value of bananas increases from

V(B)0 to V(B)1. There is no change in the absolute market value of apples.

Market Value

(EV)

“APPLES”

S

Market Value

(EV)

“BANANAS”

S

V(B)1

V(A)

V(B)0

D1

D

Q(A)

D0

Q(B)0 Q(B)1

Quantity

81

Quantity

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

…Causes the Price of Apples (in

Banana Terms) to Fall

Although there is no change in the “absolute” market value of apples, the

“relative” market value of apples, the price of apples in banana terms,

must fall as the market value of bananas rises (apples become cheaper in

banana terms). Both supply and demand curves for apples shift down.

Market Value

(EV)

“APPLES”

Apple price

(in bananas)

“APPLES”

S0

S

S1

P(A)0

V(A)

D0

P(A)1

D

Q(A)

D1

Quantity

Q(A)

82

Quantity

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

A Counterintuitive Result?

• The graphical result may seem counterintuitive: an increase in

demand for bananas shifts both the supply and demand curve for

apples. Indeed, the supply and demand curves for apples (as

expressed in banana terms) both move in the exact same direction

(downward) and by the same proportion. How is this possible?

Because both of the original supply and demand schedules (as

expressed in banana terms) assume a certain market value for the

unit of measurement (bananas).

• Consider the supply curve as measured in banana terms. If the

market value of bananas rises (bananas are more valuable), then,

all else equal, someone should be willing to supply more apples

for a given number of bananas (supply curve shifts to the right).

83

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Bananas as Currency

• Now, suppose that over time our barter economy evolves to

produce more goods. As this process evolves over time, more and

more goods are priced in “banana terms”. For examples, one

apple costs two bananas, one potato costs three bananas, one cup

of rice costs half a banana etc. Increasingly, bananas are used as

the relative measure of value (one can speak of the value of all

things in “banana terms”).

• In effect, bananas become the “currency” in our barter economy.

However, the market value of bananas will continue to fluctuate

with the result that the “general price level, in banana terms” will

generally fall when bananas are more valuable (eg. when the

banana crop fails) and rise when bananas are less valuable.

84

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Currency May Change, but the

Principle Remains the Same

• In our modern economy, we don’t use bananas as “currency” (for

many good reasons we won’t discuss here). Over time, the money

in our economy has evolved from one “good” to another. Firstly,

it evolved from the ancient equivalent of bananas to gold. Then,

governments began issuing paper claims to gold (a “asset backed

financial instrument” became money). More recently, the claim

to gold was dropped and money became a proportional claim on

output (the nature of the financial instrument changed).

• While the nature of the “good” used as money has changed, the

fundamental principle of price determination has not. The money

price of a good is determined by the relative relation between the

market value of the good and the market value of money.

85

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Supply and Demand

The Traditional Narrative

• Let’s think about price

determination in “dollar terms”.

The traditional narrative is that

supply and demand for a good

determines the equilibrium price

of that good as measured in

dollar terms.

• But what happens to the price of

the good if demand increases for

the unit of measurement (the

dollar)? Now we have a problem.

Why? Because the diagram

opposite assumes a constant

market value for money.

86

THE MARKET FOR GOOD A

IN DOLLAR TERMS

Price ($)

Supply

P(A)

Demand

Q(A)

Quantity

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Marshall’s Assumption that

“Money Retains a Uniform Value”

• Alfred Marshall, developer of “scissors analysis” (the standard

representation of supply and demand that we use today), was

well aware of the problem and the assumption of constant

money value. In relation to the demand schedule, he states:

“So far we have taken no account of the difficulties of getting

exact lists of demand prices… A list of demand prices represents

the changes in the price at which a commodity can be sold

consequent on changes in the amount offered for sale, other things

being equal; yet other things seldom are equal… To begin with, the

purchasing power of money is continually changing, and

rendering necessary a correction of the results obtained on our

assumption that money retains a uniform value.” Marshall,

(1890), Chapter III.IV.17-19 (bold emphasis added).

87

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Fixed Value of Money

• Benjamin Anderson (1917) highlights the problem with

traditional supply & demand analysis as follows:

“One point is to be added, making explicit what is implicit in the

modern theory of supply and demand. Supply and demand

doctrine assumes money, and a fixed value of money. That there

should be a given schedule of money-prices for varying quantities

of a good, is possible only if there be a given value of the moneyunit.”

• So, how do we illustrate price determination if the market value

of money is not constant (if the market value of money is not

“fixed”)? We need to illustrate supply and demand for both the

good and money separately by using an invariable unit of market

value, or “units of economic value”.

88

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Every Money Price is Determined by

Two Sets of Supply and Demand

Supply and demand for good A determines the market value of good A,

V(A). Supply and demand for money determines the market value of money,

V($). The “money price” of good A is equal to the ratio of the two market

values.

“GOOD A”

Market Value

(EV)

“MONEY”

Market Value

(EV)

S

V (A)

P(A$ ) =

V ($)

V(A)

Supply

V($)

Demand

D

Q(A)

Quantity

Q($)

89

Quantity

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

What Factors Might Cause the

Dollar Price of Good A to Rise?

• Let’s step back and think about this in simple terms. What are

the factors that might cause the price of good A, as measured in

dollar terms, to rise?

• All else equal, a rise in the market value of good A will cause the

price of good A, in dollar terms, to rise. A rise in the market

value of good A could be due to an increase in demand for good

A or a decrease in supply of good A. Either way, if V(A) rises

and V($) is constant, then the price of good A, P(A$ ) will rise.

• Alternatively, a fall in the market value of the dollar will cause

the price of good A, in dollar terms, to rise. One scenario is

illustrated on the next slide: a fall in the demand for money.

90

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

A Fall in the Market Value of the Dollar

Causes the Price of Good A to Rise

The demand curve for money shifts to the left and the market value of

money, V($), falls. Both supply and demand schedules for good A, as

expressed in money terms, rise. The absolute market value of good A, V(A),

is unchanged, but the price of good A, in dollar terms, rises.

Market Value

Of Good (A) Stable

÷

EV

EV

=

Market Value

Of Dollar Falls

Dollar Price of

Good (A) Rises

S1

Price

S

S

V($)0

P(A$)1

S0

P(A$)0

D1

D0

V(A)

V($)1

D1

D

V(A)

÷

V($)

91

D0

=

Price(A$)

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Why is the Market Value of Money not

“Front of Mind” in Negotiations?

• If the market value of money is so important, then why doesn’t it

seem to come up in many of our day-to-day negotiations? In the

case of a barter economy and an exchange of two goods (bananas

for apples) it is clear that the market value of both goods is

relevant to the ratio of exchange (the price of the trade) because

the market value of both goods tends to be quite volatile.

• But in a modern monetary economy, the market value of money

seems to be irrelevant when negotiating the dollar price of a good.

Why? Probably because it doesn’t change much: one dollar today

buys almost exactly the same as what one dollar bought yesterday

and what one dollar will buy tomorrow. In effect, the market

value of money is treated as a constant benchmark.

92

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Market Value of Money is

Negotiated in Every Trade

• It you watch negotiations between buyers and sellers of fish in

the market, then it may seem that the only thing that is being

negotiated is the market value of the fish. The market value of a

fish can fluctuate wildly based on the day’s catch.

• But ultimately, buyers and sellers are negotiating the market value

of two items: the value of the fish and the value of the money

that is being used to purchase them. A trade is successfully

concluded when the parties agree that the value of the fish is

equal to the value of the money being exchanged for the fish.

However, the negotiation over the value of money, in and of

itself, generally only becomes a real point of contention when the

value of money is fluctuating nearly as wildly as the value of fish.

93

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Foreign Exchange Markets &

The Market Value of Money

• While the “absolute market value of money” may seem to be a

somewhat abstract and obscure concept, there is one place where its

role is more easily understood: foreign exchange markets. A foreign

exchange rate is the price of one currency in terms of another. A

foreign exchange rate, like any price, is a ratio of two quantities

exchange: a certain number of units of one currency for a certain

number of another.

• How is this particular ratio of exchange determined? Once again, we

can invoke the rule that for an exchange to be successfully

conducted, the total market value of one basket exchanged must be

equal to the total market value of the other. Therefore, the ratio of

quantities exchange is the reciprocal of the ratio of the absolute

market value of the two currencies.

94

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Foreign Exchange Rate

Determination

• The principle of trade equivalence states that, in an efficient

market, the two baskets of goods being exchanged must be equal

in total market value. Therefore, if one currency (the Euro) is

exchanged for another (the US Dollar), then:

V(EUR)×Q(EUR) = V(USD)×Q(USD)

• Supply and demand for US Dollars determines the market value

of the US Dollar V(USD). Similarly, supply and demand for

Euros determines V(EUR). The USD/EUR exchange rate is then

equal to:

Q(USD) V(EUR)

P(EURUSD ) =

=

Q(EUR) V(USD)

95

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Determination of USD/EUR

Exchange Rate

The USD/EUR exchange rate (Dollars per Euro, or P(EURUSD) is

determined by the ratio {V(EUR)/V(USD)}. The market value of the each

currency is determined by supply and demand for that particular currency.

“EUROS”

“US DOLLARS”

EV per Euro

EV per USD

S

V (EUR)

P(EURUSD ) =

V(USD)

V(EUR)

S

V(USD)

D

D

Q(EUR) Money (Base)

96

Q(USD)

Money

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

A Fall in the Value of the USD…

Demand for US Dollars falls and the absolute market value of the USD,

V(USD), falls. There is no change in the absolute market value of the EUR.

What happens to the USD/EUR (Dollars per Euro) exchange rate?

“EUROS”

“US DOLLARS”

EV per Euro

EV per USD

S

S

V(USD)0

V(EUR)

V(USD)1

D

D1

D0

Quantity

Quantity

97

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

…Leads to a Rise in the

Price of EURs (in USD Terms)

There is no change in the absolute market value of the EUR, but the relative

market value of EUR (the price of EUR in USD) rises as the value of the

USD falls and demand and supply for Euros, in USD terms, are rebased.

“EUROS (EV Terms)”

“EUROS (USD terms)”

EV per Euro

USD per Euro

S

S0 = S1

P(EUR)1

V(EUR)

P(EUR)0

D

D0

Q(EUR) Quantity

Q(EUR)

98

D1

Quantity

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Matrix of Market Values

• In our example, we focus on the determination of one price,

P(EURUSD). The market value of the USD falls and the price of

Euros, in USD terms, rises. In practice, a fall in the absolute

market value of the USD will, all else equal, raise the price of all

currencies in terms of USD. This phenomenon can be observed

by watching a display of foreign exchange cross rates.

• In essence, the foreign exchange cross rates that we see are the

physical manifestation of a matrix of unobservable absolute

market values. Every currency has a market value: we can’t

observe the absolute market value of each currency (as measured

in units of economic value) but we an observe the relative market

value of each currency in terms of the others (the “cross rates”).

99

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Prices are the Observable Portion of

a Matrix of Market Values

This general principle extends to all prices: every price we see, whether it be

the barter price of a good, the money price of a good or a foreign exchange

rate, is the relative relation of two directly unobservable absolute market

values. Consider the simple example below with two goods and two

currencies. Absolute market values are in the dark shade. Prices, in the light

shade, are calculated as (EV top row)/(EV first column).

Good (EV)

Apple (5)

Banana (10)

USD (2.5)

EUR (5)

Apple (5)

1

2

0.5

1

Banana (10)

0.5

1

0.25

0.5

USD (2.5)

2

4

1

2

EUR (5)

1

2

0.5

1

100

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Explaining the Matrix

• On the previous slide, there is a matrix of market values.

Absolute market values (in the darker shade) are across the top

row and first column: these can not be directly observed. Relative

market values (in the lighter shade) can be directly observed as

“prices”.

• For example, the price of apples in USD terms is equal to $2 per

apple (5/2.5 = 2). The price of USD in banana terms (notice I

have flipped the unit of measurement) is equal to 0.25 bananas

per USD. The price of EUR in USD terms is 2 USD per Euro.

• Now, let’s change one input. If the absolute market value of USD

falls from 2.5 to 2, then what happens to the prices in the matrix?

101

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Impact of a Fall in the Absolute

Market Value of US Dollars

If the market value of the USD falls (from 2.5EV to 2EV), then the

price of all goods in USD terms rises, as indicated by the row of green

numbers. For example, the price of apples in USD terms rises from $2

per apple to $2.5 per apple. Conversely, the price of USD in terms of all

other goods falls, as indicated by the column of red numbers.

Good (EV)

Apple (5)

Banana (10)

USD (2)

EUR (5)

Apple (5)

1

2

0.4

1

Banana (10)

0.5

1

0.2

0.5

USD (2)

2.5

5

1

2.5

EUR (5)

1

2

0.4

1

102

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

The Relative Volatility of

Different Types of Prices

• In practice, price determination is not quite as simple as the matrix

on the previous slide suggests. For example, foreign exchange rates

are highly volatile on an intra-day and intra-month basis, whereas

the money price of of a good (for example, the dollar price of

bananas) is very stable on an intra-day basis and relatively stable on

an intra-month basis.

• This phenomenon suggests that there is some inertia built into

goods prices: for example, “menu costs” may discourage vendors

from regularly changing display prices. Nevertheless, just because

some prices (forex rates) exhibit more volatility than others (money

prices of goods), does not mean that they are not determined by the

same fundamental process. Ultimately, every price is a relative

expression of two market values.

103

Gervaise R. J. Heddle, 2014

Review and Path Forward