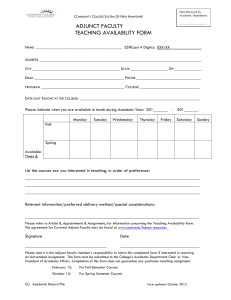

Chapter 17 Supporting Adjunct Faculty

advertisement