Federalism Chapter Summary I. Defining Federalism (66

advertisement

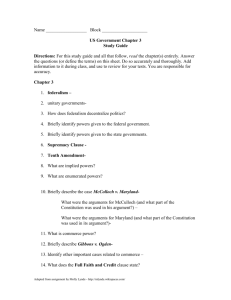

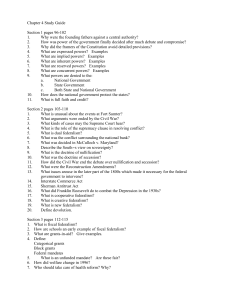

Federalism Chapter Summary I. Defining Federalism (66-70) A. What Is Federalism? Federalism is a way of organizing a nation so that two or more levels of government have formal authority over the same area and people. Power is shared between units of government. Most governments in the world, like Great Britain, are unitary governments, in which all power resides in the central government. The American states are unitary governments with respect to their local governments. A confederation is a governmental structure in which the national government is weak and most power is in the hands of its components, or states. The term intergovernmental relations refers to the interactions among national, state, and local governments. B. Why Is Federalism So Important? Federalism decentralizes our politics in many ways. For example, senators are elected to represent their state, not the nation. With more levels of government, more opportunities exist for political participation. Judicial power also is enhanced by federalism. Federalism also decentralizes our policies. The history of federalism demonstrates the tension between the states and the national government over who should control policy. The overlapping powers of the two levels of government mean that most debates over policy become debates over federalism. States are responsible for most public policies dealing with social, family, and moral issues. These become national issues when brought to the national government by an aggrieved group. The American states are also policy innovators, being responsible for many reforms, new ideas, and new policies. II. The Constitutional Basis of Federalism (70-76) A. The Division of Power The powers of state and national governments are carefully defined in the Constitution. States are guaranteed equal representation in the Senate, are responsible for elections, and cannot be abolished. The national government must protect states from violence and invasion. The supremacy clause states that the Constitution, laws of the national government, and treaties are the supreme law of the land. However, the Tenth Amendment states “powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.” This amendment has led to much controversy over the realm of the states’ powers. The Supreme Court has ruled that the Tenth Amendment did not give states power superior to that of the national government for activities not mentioned in the Constitution. The authority of the national government has been challenged by the states. Federal courts can order states to obey the Constitution or federal laws and treaties. The Eleventh Amendment prohibits individual damage suits against state officials and protects state governments from being sued against their consent by private parties in federal or state courts. B. Establishing National Supremacy Four key events have largely settled the issue of how national and state powers are related. In the Supreme Court case of McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) Chief Justice John Marshall established two important constitutional principles. The first was the supremacy of the national government over the states, which suggests that federal laws preempt state laws and thus preclude their enforcement. The second was the principle that the national government has certain implied powers that go beyond enumerated powers. The Constitution states that Congress has the power to “make all laws necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers.” Today implied powers are often stretched to the limit, referring to the necessary and proper clause as the elastic clause. In Gibbons v. Ogden (1824) the Supreme Court increased the power of the federal government to regulate interstate commerce by broadly defining commerce to encompass virtually every form of commercial activity. However, the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the federal government’s power to regulate interstate commerce has fluctuated. In recent years the Court has placed limitations on the national government’s commerce power. The Civil War and the struggle for equality have also helped define the powers of the national and state governments. The Civil War was essentially a struggle between the power of the states and the power of the national government. The struggle for equality pitted states’ rights against national power. The conflict between states and the national government over equality issues was decided in favor of the national government. C. States’ Obligations to Each Other The Constitution outlines certain obligations that each state has to every other state. Article IV requires that states give full faith and credit to the public acts, records, and civil judicial proceedings of every other state. This is essential to the functioning of society and the economy. Usually full faith and credit is not an issue, although the recent issue over same-sex marriages has become controversial. Extradition is the constitutional requirement that states return a person charged with a crime in another state to that state for trial or imprisonment. The most complicated obligation among the states is the requirement that citizens of each state receive all the privileges and immunities of any other state in which they happen to be. There are many exceptions to this obligation; however the more fundamental the right, the less likely a state can discriminate against citizens of another state. III. Intergovernmental Relations Today (77-84) A. From Dual to Cooperative Federalism In dual federalism both the national government and the states remain supreme within their own spheres, each responsible for certain policies. Mingled responsibilities and blurred distinctions between the levels of government characterize cooperative federalism. Powers, policy, costs, administration, and blame are shared between the national government and the states. Before the national government began to assert its dominance over state governments, the American federal system leaned toward dual federalism. Gradually, the national role expanded until today the federal government’s presence is felt almost everywhere. Cooperative federalism rests on three standard operating procedures: shared costs, federal guidelines, and shared administration. The cooperation between the national and state governments is such an established feature that it persists even when the two levels of government are in conflict on certain matters. Most Americans see the national government as more capable of handling some issues and the state and local governments as better at others. The Republican majority that captured Congress in 1995 passed bills to give the states more authority over social and environmental programs once seen as the realm of the national government. However, Republicans also found the federal government was the most effective way to achieve many of their policy objectives. B. Fiscal Federalism Fiscal federalism is the pattern of spending, taxing, and providing grants in the federal system. There are two major types of federal aid to the states. Categorical grants are the main source of federal aid. They can be used only for one of several hundred specific purposes. Categorical grants often have strings attached, such as a nondiscrimination provision. The federal government may employ cross-over sanctions to use federal dollars in one program to influence state and local policy in another. Cross-cutting requirements occur when a condition on one federal grant is extended to all activities supported by federal funds regardless of their source. There are two types of categorical grants. Project grants are awarded on the basis of competitive applications. Formula grants are distributed according to a formula, often based on population, income, percentage of rural population, or other factors. The second major type of federal aid to the states is block grants, which are given more or less automatically to states or communities, which then have discretion in deciding how to spend the money. Block grants are now on the increase. A general rule of federalism is that the more money there is at stake, the more fervently people will argue about its distribution. Consequently, states and localities often act as interest groups, competing with each other for federal dollars. On the whole, however, federal grant distribution tends to follow the principle of universalism, something for everybody. Sometimes federal aid puts an unwanted burden on state governments. Most federal grants require the states to pay for a percentage of the costs; thus they have to budget funds for the project just to receive federal grant money. Requirements that direct states or local governments to comply with federal rules under threat of penalties or as a condition of receipt of a federal grant are called mandates. Unfunded mandates occur when Congress passes a law creating financial obligations for the states but provides no funds to meet these obligations. The Republican Congress has tried to limit the use of unfunded mandates, but federal courts and regulatory rules continue to impose financial burdens on the states. IV. Understanding Federalism (84-90) A. Federalism and Democracy The founders established a federal system in part to allay the fears of those who believed that a powerful and distant central government would tyrannize the states and limit their voice in government. Federalism has many advantages for democracy. It creates more opportunities for participation in politics. It increases access to government. Citizens and interest groups have more places to bring their grievances. Federalism allows the diversity of opinion within the country to be reflected in different public policies among the states. By handling most disputes over policy at the state and local level, federalism also reduces decision-making and conflict at the national level. Federalism can also have disadvantages for democracy. States differ in the resources they can devote to services; thus, quality of services can vary widely between the states. Diversity in policy can also discourage states from providing services that would otherwise be available. Federalism may also have a negative effect on democracy insofar as local interests are able to thwart national majority support of certain policies, as occurred with civil rights policies. Finally, the sheer number of governments in the United States can be a burden to democracy. B. Federalism and the Growth of the National Government Throughout our history the national government has responded to needs and problems with new public policies, especially in the area of the economy. Relevant interests tend to turn to the national government for help. The states usually do not have the authority and resources to deal with most problems. Although it is constitutionally permissible for the states to handle a wide range of issues (except defense policy) it is usually not a sensible alternative. It would not be logical for the states, for example, to have their own space program, energy policy, retirement program, etc. Accordingly, the national government’s share of American governmental expenditures has grown rapidly since 1929. Although states have not been supplanted by the national government, the national government has taken on many new responsibilities.