Criminal Law Society Moot Brief

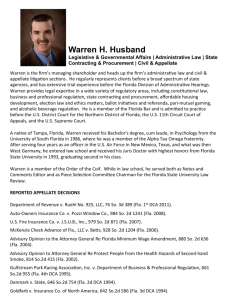

advertisement

THE 2013 WECHSLER MOOT COURT COMPETITION UNIVERSITY AT BUFFALO LAW SCHOOL | MARCH 2013 In the Supreme Court of the United States OCTOBER TERM 2012 NO. 12 – 1234 ________________________________________________ DOE, ET. AL, Petitioners V. FLORIDA, Respondent. ________________________________________________ ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATED COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT ________________________________________________ BRIEF FOR THE RESPONDENT TEAM 9 Team #9 QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Whether the Florida Legislature may constitutionally eliminate mens rea as an element of certain drug-related offenses? Respondent says yes. 2. Whether the availability of an affirmative defense through which an accused may establish a lack of knowledge of the illicit nature of the substance satisfies any constitutional concerns raised by the state’s elimination of a mens rea element with respect to such offenses. Respondent says yes. 2 Team #9 TABLE OF CONTENTS QUESTIONS PRESENTED............................................................................................................2 TABLE OF CONTENTS….............................................................................................................3 TABLE OF AUTHORITIES...........................................................................................................5 STATEMENT OF THE CASE.......................................................................................................8 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT............................................................................................13 ARGUMENT I. The Amendment of a Criminal Statute Constitutes a Valid Exercise of the State’s Power to Make Reasonable Policy Determinations…...........................................14 A. Amendment Section 893.101 is a Legitimate Use of the State’s Powers as Imagined By the Framers, Provided for in the Constitution and Promoted in This Court……................................................................................................14 B. The State Promotes National and Local Interests in its Reasonable Policy Determination As Embodied by Amendment § 893.101.................................17 II. Elimination of Mens Rea is Not in and of Itself a Violation of Due Process.................................................................................................................. 18 A. Historically, This Court has been Unwilling to Rule Criminal Statutes Unconstitutional in Light of States’ Broad Police Power................................18 B. Amendment Section § 893.101 Creates a General Intent Crime, Voiding Notice Concerns…….……………...………………………………………..20 III. The Availability of an Affirmative Defense Eliminates Remaining Objections to Amendment Section § 893.101……...…………………………………………...21 3 Team #9 A. Lack of Knowledge Defense Proves Legislature Did Not Intend to Create a Strict Liability Crime..…...…………………………………………………..22 B. The Government Bears the Burden of Proof for the Elements of the Offense and Bears the Burden of Proof to Overcome an Affirmative Defense............23 CONCLUSION.............................................................................................................................26 4 Team #9 TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Constitutional Provisions: U.S. Const. Art. I § 9, cl. 3……………………………………………………………………….16 U.S. Const. amend. X…………………………………………………………………………….14 United States Supreme Court Cases: Ewing v. California, 538 U.S. 11 (2003).……………………………………………………15, 18 Gregory v. Ashcroft, 501 U.S. 452 (1991).………………………………………………………17 In re Winship, 397 U.S. 358 (1970)..…………………………………………………………….23 Lambert v. People of the State of California, 355 U.S. 225 (1957)………………...……19, 20, 21 Martin v. Ohio, 480 U.S. 228 (1987)..……………………………………………………….23, 24 McFarland v. American Sugar Rfg. Co., 241 U.S. 79 (1916).…………………………………..16 Montana v. Egelhoff, 518 U.S. 37 (1996).…………………………………………………...15, 18 Morissette v. United States., 342 U.S. 246 (1952)………………………………………………...9 Patterson v. New York, 432 U.S. 197 (1977)…………...……………………14, 15, 16, 19, 23, 24 Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513 (1958)…………………………………………………………19 Staples v. United States, 511 U.S. 600 (1994)……………………………………….……9, 22, 23 Tot v. United States, 319 U.S. 463 (1943)………………………………………………………16 United States v. Balint, 258 U.S. 250 (1992)….…………………………...……….…………9, 19 United States v. Darby, 312 U.S. 100 (1941)….……………………………..……….…………14 Federal Cases: Shelton v. Sec’y, Dept. of Corr., 802 F. Supp. 2d 1289 (M.D. Fla. 2011)….....................11, 12, 22 Shelton v. Sec’y, Dept. of Corr., 691 F.3d 1348 (11th Cir. 2012)………………………...…12, 19 United States v. Averi, 715 F. Supp. 1508 (M.D. Ala. 1989) ………………………...…………19 5 Team #9 United States v. Bunton, 2011 WL 5080307 N.8:10-CR-327-T-30EAJ (M.D. Fla. Oct. 26, 2011)..............................................................................................................................................11 United States v. Cordoba-Hincapie, 825 F. Supp 485 (E.D. N.Y. 1993)…………………………9 State Court Cases: Chicone v. State, 684 So. 2d 736 (Fla. 1996)…………………………………………………9, 10 Flagg v. State, 74 So. 3d 138 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2011)……………………………………22, 24 Maestas v. State, 76 So. 3d 991 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2011)…...…………………………18, 20, 22 Miller v. State, 35 So. 3d 162 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2010)…….…...…………………………11, 12 Scott v. Cohen, 568 So. 2d 49, 51 (Fla. 1990)…….…...………………………………………...23 Scott v. State, 808 So. 2d 166 (Fla. 2002)…….…...……………………………………………..10 State v. Adkins, 96 So. 3d 412 (Fla. 2012)….…...……………………………………………….11 Statutes: Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.03(1) (West 2012)…………………………………………………………..8 Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.03(2) (West 2012)…………………………………………………………..8 Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.03(3) (West 2012).………………………………………………………….8 Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.101 (West 2002)…..10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.101(1) (West 2002).………………………………………………………10 Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.101(2) (West 2002)……………………………………………………10, 21 Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.101(3) (West 2002)..………………………………………………………10 Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.13 (West 2012)……………………………………..8, 10, 11, 14, 20, 21, 22 Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.13(1)(a) (West 2012).………………………………………………………8 Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.13(2) (West 2012)……………..……………………………………………8 Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.13(3) (West 2012)………………..…………………………………………8 6 Team #9 Secondary Sources: 16 Fla. Jur. 2d Criminal Law § 129 (2013)……………………………………………………...21 21 Am. Jur. 2d Criminal Law § 132 (2013)……………………………………………………...10 21 Am. Jur. 2d Criminal Law § 135 (2013)……………………………………………………...10 Fla. Std. Jury Instr. (Crim.) 25.7. (2007)………………………………………………………...24 Jiaquan Xu et al., Deaths: Final Data for 2007, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 58 National Vital Statistics Reports 19 (2007), available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr58/nvsr58_19.pdf………………..............................17 Rachel A. Lyons, Florida’s Disregard of Due Process Rights for Nearly A Decade: Treating Drug Possession as a Strict Liability Crime, 24 St. Thomas L. Rev. 350 (2012)……………20 The Federalist No. 47, at 292-93 (James Madison) (Clinton Rossiter ed., 1961)………….........15 7 Team #9 STATEMENT OF THE CASE The Florida Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act (“DAPCA”) prohibits “any person to sell, manufacture, or deliver, or possess with intent to sell, manufacture, or deliver, a controlled substance.” Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.13(1)(a) (West 2012). The DAPCA distinguishes between controlled substances in order to determine the severity of the criminal offense. Substances listed in Schedule I have “a high potential for abuse and [have] no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States and [their] use under medical supervision [do] not meet accepted safety standards.” Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.03(1) (West 2012). An offender in possession of such substances “commits a felony of the second degree.” Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.13(1) (West 2012). Substances in Schedule II have “a high potential for abuse,” but are distinguishable from Schedule 1 substances because they are used in “currently accepted but severely restricted medical use in treatment in the United States, and abuse of the substance may lead to severe psychological or physical dependence.” Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.03(2) (West 2012). An offender in possession of such substances “commits a felony of the third degree.” Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.13(2) (West 2012). Finally, substances in Schedule III have a “potential for abuse less than the substances contained in Schedules I and II and [have] a currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States, and abuse of the substance may lead to moderate or low physical dependence or high psychological dependence.” Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.03(3) (West 2012). An offender in possession of such substances “commits a misdemeanor of the first degree.” Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.13(3) (West 2012). 8 Team #9 Before 2002, the DAPCA was silent as to a mens rea requirement. The term “mens rea” means “‘a guilty mind; a guilty or wrongful purpose; a criminal intent’” and is also “shorthand for a broad network of concepts encompassing much of the relationship between the individual and the criminal law.” U.S. v. Cordoba-Hincapie, 825 F.Supp. 485, 489 (E.D.N.Y. 1993). Although mens rea is “deeply rooted in our legal tradition,” Judge Weinstein observed that “like most ancient doctrines, however, it has grown far more sophisticated and nuanced than it once was. It can no longer simply be invoked. Its application must be carefully explained and its many distinctions must be considered. Not only has the law developed an appreciation of gradations in mental states, but it now also openly recognizes limited exceptions to a rule once characterized as admitting no compromise.” Id. at 496. The Florida Supreme Court considered whether DAPCA was one such exception to the rule in in Chicone v. State where it contended with the conspicuous absence of mens rea in the statute. The Chicone Court observed “the state of the law on this issue is unclear” and pointed to number of conflicting decisions from the district courts as to whether the knowledge is an element of the offenses listed in the DAPCA. Chicone v. State, 684 So.2d 736, 738 (Fla. 1996). Drawing upon the holdings of this Court, the Florida Supreme Court concluded that “the legislature is vested with the authority to define the elements of a crime, determining whether scienter is an essential element of a statutory crime is a question of legislative intent.” Id. at 741 (citing Morissette v. United States, 342 U.S. 246 (1952)), Staples v. United States, 511 U.S. 600 (1994), and United States v. Balint, 258 U.S. 250 (1992) . The Chicone Court concluded “it was the intent of the legislature to prohibit the knowing possession of illicit items” and accordingly held there was an implicit mens rea requirement for the possession of the substances listed in the statute. Id. at 744. 9 Team #9 The Florida Supreme Court later expanded this understanding of legislative intent. The Scott Court held in addition to knowing possession, the statute also required “knowledge of the illicit nature of the contraband is an element of the crime of possession of a controlled substance.” Scott v. State, 808 So. 2d 166, 172 (2002). Shortly after the Scott decision, the Florida Legislature clarified its intent by enacting an amendment to DAPCA. Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.101 (West 2002). Amendment Section 893.101 codified that the holdings in Chicone and Scott were “contrary to legislative intent.” Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.101(1) (West 2002). Rather, the Legislature posited that “knowledge of the illicit nature of a controlled substance is not an element of any offense under this chapter.” Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.101(2) (West 2002). Thus, the Scott Court’s additional mens rea requirement was struck from the elements of the offenses listed in DAPCA. Instead, Amendment Section 893.101 permits the accused to raise “lack of knowledge of the illicit nature of a controlled substance” as an “affirmative defense to the offenses of this chapter.” Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.101(2) (West 2002). The accused may raise an affirmative defense of lack of knowledge to rebut the “permissive presumption that the possessor knew of the illicit nature of the substance.” Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.101(3) (West 2002). The elimination of all knowledge requirement would essentially reduce the offenses listed in Section § 893.13 to strict liability crimes, which “depend on no mental element” and are “generally disfavored.” 21 Am. Jur. 2d Criminal Law § 132; 21 Am. Jur. 2d Criminal Law § 135. However, Amendment Section 893.101 does not eliminate all mens rea for the offenses listed in DAPCA. State v. Adkins, 96 So. 3d. 412, 416 (Fla. 2012); United States v. Bunton, 2011 WL 5080307 N.8:10-CR-327-T-30EAJ at *1 (M.D. Fla. Oct. 26, 2011) 10 Team #9 . Rather, the aggregate effect of the amendment is to create a general intent crime. A general intent crime “is one in which an act was done voluntarily and intentionally, and not because of mistake or accident.” ALR 21 Am. Jur. 2d Criminal Law § 118. Essentially, the government must prove the “defendant intended deliberate, conscious, or purposeful action, as opposed to causing a prohibited result through accident, mistake, carelessness, or absentmindedness.” Id. As the Florida Supreme Court later confirmed in State v. Adkins, Amendment Section 893.101 does not “eliminate the element of knowledge of the presence of the substance.” Adkins at 416. The Adkins Court observed that “since the enactment of section 893.101, each of the district courts of appeal has ruled that the statute does not violate the requirements of due process.” Id. With the exception of one case, the federal courts in Florida have upheld this interpretation of Amendment Section 893.101. Adkins at 416; See Shelton v. Sec’y, Dept. of Corr., 802 F. Supp. 2d 1289 (M.D. Fla. 2011). As the Middle District observed, “While the statute has no element requiring guilty knowledge of the illicit nature of the substance, the State still must prove that a defendant charged with a drug offense enumerated in Fla. Stat. § 893.13 had knowledge of his possession of the substance.” Bunton at *1. This interpretation reflects actual practice in Florida as jury instructions include a finding of knowledge of the possession. In Miller v. State, the court considered the following jury instructions: “to prove the crime of possessing cocaine, the State must prove three elements beyond a reasonable doubt. First, they have to prove that Mr. Miller possessed a certain substance. Second, that the substance was cocaine. And third, that Mr. Miller had knowledge of the presence of the substance.” Miller v. State, 35 So. 3d 162, 163 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2010). 11 Team #9 The law appeared well settled on this issue until a judge in the Middle District of Florida challenged the accepted interpretation of Amendment Section 893.101. In Shelton v. Sec’y of the Dept. of Corr., the court granted a habeas petition having found “petitioner’s facial challenge to Florida's drug statute is properly premised on allegations that the State's affirmative elimination of mens rea and scienter from this felony offense violates due process.” Shelton v. Sec’y, Dept. of Corr., 802 F. Supp. 2d 1289, 1297 (M.D. Fla. 2011). As a result of this perceived violation of due process, the court held the Amendment Section 893.101 was facially unconstitutional. The Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals struck down this holding. The court found that the Amendment Section 893.101 was “explicit in its partial elimination of mens rea.” Shelton v. Sec’y, Dept. of Corr., 691 F. 3d 1348, 1355 (11th Cir. 2012). The Eleventh Circuit found it reasonable that five Florida Supreme Court justices “agreed no U.S. Supreme Court precedent renders the Act as amended unconstitutional” and accordingly, deferred to the state court decision and reversed the lower court’s grant of habeas relief. Id. at 1354. In the instant matter, the constitutionality of Amendment Section 893.101 is challenged again. Doe v. Florida considers the constitutionality of convictions for violations of the entire range of offenses listed in Florida Statute Section 893.13. These misdemeanor and felony convictions were affirmed, as keeping with the settled state of the law, by the highest state courts of Florida. 12 Team #9 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT The Florida legislature did not violate due process by eliminating mens rea as an element of certain drug-related offenses in Section 893.101. Amending a criminal statute to clarify intent is a valid exercise of a state’s power. Moreover, this Court has repeatedly held that elimination of mens rea as an element of an offense is not a violation of due process if the state’s interest in doing so does not violate societal notions of fundamental fairness and provides proper notice to individuals. Assuming that all mens rea was in fact eliminated by Section 893.101, the balancing between the state’s police power and the fact that elimination of mens rea is not in and of itself impermissible satisfies fairness concerns. The notice requirement is met when the conduct that is being regulated is one that would be expected to be regulated. In the instant case, even assuming that the legislature eliminated all mens rea from the drug-related offenses, allowing for an affirmative defense that an individual charged under one of the offenses did not know about the illicit nature of the substance ameliorates any due process concerns. The availability of the affirmative defense ensures that the offenses in questions are not strict liability crimes, and strict liability crimes are what generally trigger due process concerns. Additionally, the affirmative defense does not ask a defendant to prove an element of the underlying offense, thus there is not an inappropriate shift of proof to defendants. As such, the availability of the affirmative defense created by the statute installs the necessary procedural safeguard to foreclose any due process concerns. 13 Team #9 ARGUMENT I. The Amendment of a Criminal Statute Eliminating Mens Rea Constitutes a Valid Exercise of the State’s Power to Make Reasonable Policy Determinations Amendment Section 893.101 State Legislature’s clarification of its intent and the elements of Section 893.13 offenses is: (1) a constitutionally permissible exercise of state power that does not exceed any articulated limitations on this power; and (2) a rational policy choice on the part of the State to promote national and local interests. As this Court observed, “Traditionally, due process has required that only the most basic procedural safeguards be observed; more subtle balancing of society’s interests against those of the accused have been left to the legislative branch.” Patterson v. New York, 432 U.S. 197, 201-02 (1977). A. Amendment § 893.101 is a Legitimate Use of the State’s Powers as Imagined By the Framers, Provided for in the Constitution and Promoted in This Court The State appropriately exercised its powers, as vested by the Constitution, when the Legislature enacted Amendment Section 893.101. The Tenth Amendment provides that each state retain “its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this Confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled.” U.S. Const. amend. X. The Supreme Court famously held this “amendment states but a truism that all is retained which has not been surrendered.” United States v. Darby, 312 U.S. 100, 124 (1941). The framers intended to vest the states with expansive authority to “allay fears that the new national government might seek to exercise powers not granted, and that the states might not be able to exercise fully their reserved powers.” Id. These reserved powers were contemplated as extending “to all the objects which, in the ordinary course of affairs, concern the lives, liberties and properties of the people and the 14 Team #9 internal order, improvement, and prosperity of the State.” The Federalist No. 47, at 292-93 (James Madison) (Clinton Rossiter ed., 1961). Criminal statutes concern the “lives, liberties and properties of the people” because they impose sentences and fines. Id. Legislative attempts to modify these statutes, with the goal of bolstering “the internal order, improvement and prosperity of the State,” are an appropriate use of the powers imagined by the framers. Id. Under the Constitution, the states properly create, modify, and implement criminal statutes. Patterson v. New York, 432 U.S. 197, 201-02 (1977). The Patterson Court found “preventing and dealing with crime is much more the business of the States than it is of the Federal Government, and ... we should not lightly construe the Constitution so as to intrude upon the administration of justice by the individual States.” Id. This Court has generally upheld the state’s power to modify responses to criminal activity by legislative initiative. Ewing v. California, 538 U.S. 11, 12 (2003). In Ewing, the Court considered California’s three strikes law, the second state to pass a legislative initiative of this kind in the nation; Washington was the first state to pass such a law. Id. at 15. The Ewing Court found “State legislatures enacting three strikes laws made a deliberate policy choice… Though these laws are relatively new, this Court has a longstanding tradition of deferring to state legislatures in making and implementing such important policy decisions.” Id. at 12. See also Montana v. Egelhoff, 518 US 37, 44 (1996): “Preventing and dealing with crime is much more the business of the States than it is of the Federal Government, and ... we should not lightly construe the Constitution so as to intrude upon the administration of justice by the individual States.” However, a state cannot run afoul of other constitutional provisions when exercising its powers. In Patterson, this Court upheld the state legislature’s modification of a criminal statute to 15 Team #9 permit defendants to bear the burden of proof of an affirmative defense. Patterson v. New York, 432 U.S. 197, 210 (1977). While finding in that instance there was no violation of Due Process, the Court recognized that “there are obviously constitutional limits” to the broad powers enjoyed by the states. Id. First, states are prohibited from creating bill of attainders. The Patterson Court held “’it is not within the province of a legislature to declare an individual guilty or presumptively guilty of a crime.’” Patterson at 210 (citing McFarland v. American Sugar Rfg. Co., 241 U.S. 79, 86 (1916)). Legislative declarations of guilt, or bills of attainder, are barred by explicit language in the Constitution. U.S. Const. Art. I § 9, cl. 3. Secondly, the government must bear the burden of proof for all materials elements of the offense. The Patterson Court held the state legislature cannot “validly command that the finding of an indictment, or mere proof of the identity of the accused, should create a presumption of the existence of all the facts essential to guilt.” Patterson at 210 (citing Tot v. United States, 319 U.S. 463, 469 (1943)). In the instant matter, Florida acts by the powers granted by the Constitution to modify the certain criminal offenses as provided for in Amendment Section 893.101. First, this modification does not infringe upon any stated constitutional protections or provisions. Secondly, this modification is compatible with the kind of powers the framers imagined were reserved by the states. Finally, Amendment Section 893.101 respects the limitations on the states’ powers as articulated by this Court: it neither declares an individual guilty of a crime nor discharges the government’s burden of proof. 16 Team #9 B. The State Promotes National and Local Interests in its Reasonable Policy Determination As Embodied by Amendment 893.101 When state legislatures appropriately exercise their powers to self-determine, the nation benefits from their diverse policy initiatives. Gregory v. Ashcroft 501 U.S. 452, 458 (1991). In Gregory, this Court observed that the “federalist structure of joint sovereigns preserves to the people numerous advantages. […] it increases opportunity for citizen involvement in democratic processes; it allows for more innovation and experimentation in government; and it makes government more responsive by putting the States in competition for a mobile citizenry.” Id. Furthermore, the states are in the best position to know and respond to the “diverse needs” of their populace. Id. An additional advantage of the federalist system, as observed by the Gregory Court, is that it “assures a decentralized government that will be more sensitive to the diverse needs of a heterogeneous society.” Id. The State promotes national policy to eradicate the illegal use and sale of narcotics by Amendment Section 893.101, and additionally acts in its own self-interest by responding to the presence of illegal drugs and drug use contained within its borders. As a direct consequent of drug use, 2,936 persons died in Florida in 2007.1 This is compared to the number of persons in Florida who died from motor vehicle accidents (3,329) and firearms (2,272) in the same year.2 Florida drug-induced deaths (16.1 per 100,000 population) exceeded the national rate (12.7 per 100,000 population).3 1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention - National Vital Statistics Reports Volume 58, Number 19 for 2007. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr58/nvsr58_19.pdf 2 Id. 3 Id. 17 Team #9 For the aforementioned reasons, Amendment Section 893.101 is a constitutionally permissible, innovative policy determination that promotes the order and wellbeing of the State of Florida’s populace. II. Elimination of Mens Rea is Not in and of Itself a Violation of Due Process The Florida legislature did not violate due process or otherwise create an unconstitutional criminally punishable offense in enacting Amendment Section 893.101. This Court has consistently held that the elimination of mens rea is not in and of itself a violation of due process. As long as the State ensures that general principles of fairness are maintained—primarily by ensuring that individuals have proper notice about what type of behavior the State is criminalizing—this Court has been unwilling to rule criminal statutes unconstitutional. Additionally, in the instant case, lower courts have held that the statute does not completely eliminate mens rea, but rather creates a general intent crime. See Maestas v. State, 76 So.3d 991. Lastly, even assuming that Amendment Section 893.101 does completely eliminate mens rea as an elements of certain drug crimes, it also provides for the availability of an affirmative defense, discussed infra in section III, wherein individuals can assert a lack of knowledge as to the illicit nature of the regulated substances. This provides sufficient procedural safeguards to alleviate any and all due process concerns. A. Historically, This Court has been Unwilling to Rule Criminal Statutes Unconstitutional in Light of States’ Broad Police Power Petitioners contend that eliminating the mens rea element of certain drug-related offenses via statute constitutes a violation of due process. As already addressed, this Court has historically afforded great deference to states in designing their own criminal justice systems. See Ewing v. California, 538 U.S. 11, 12 (2003); Montana v. Egelhoff, 518 U.S. 37 (1996). Under this 18 Team #9 standard, due process is only violated when a state law or policy “offends some principle of justice so rooted in the traditions and conscience of our people as to be ranked as fundamental.” Patterson v. New York, 432 U.S. 197, 201 (1977) (citing Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513, 523 (1958)). In light of a state’s broad police power, there have been few instances where this standard has been found satisfied. This Court long ago specifically rejected the principle argument that petitioners make regarding the due process violation, that “punishment of a person for an act in violation of law when ignorant of the facts making it so, is an absence of due process of law.” United States v. Balint, 258 U.S. 250, 251 (1992). See also United States v. Averi, 715 F. Supp. 1508 (M.D. Ala. 1989) (holding “that the Government was not required to prove defendant was aware of record-keeping requirements as element of crime”); Lambert v. People of the State of California, 355 U.S. 225, 228 (1957) (“We do not go with Blackstone in saying that ‘a vicious will’ is necessary to constitute a crime…for conduct alone without regard to the intent of the doer is often sufficient. There is wide latitude in the lawmakers to declare an offense and to exclude elements of knowledge and diligence from its definition”). In fact, this Court’s aversion to invalidating criminal statutes on due process concerns is so strong that, as the court in Shelton commented, “it suffices to note that only once, in Lambert v. California, has the Supreme Court held a criminal provision unconstitutional under the Due Process Clause for failing to require sufficient mens rea.” Shelton v. Sec’y. Dept. of Corr., 691 F.3d 1348, 1354 (11th Cir. 2012). 19 Team #9 B. Amendment Section § 893.101 Creates a General Intent Crime, Voiding Notice Concerns Although the elimination of mens rea for criminal offenses has been found constitutional and not in violation of due process, the concern of notice still remains—“engrained in our concept of due process is the requirement of notice. Notice is sometimes essential so that the citizen has the chance to defend charges.” Id. Commentators have critiqued the Florida statute as effectively casting too broad a net, creating a scope that “overreaches the constitutional limitations in place for criminal laws.” Rachel A. Lyons, Florida's Disregard of Due Process Rights for Nearly A Decade: Treating Drug Possession As A Strict Liability Crime, 24 St. Thomas L. Rev. 350, 375-76 (2012). The argument here is that “an innocent person possessing or engaging in” activities such as carrying a backpack/container “could find him or herself in an unfortunate situation where by way of another individual…controlled substances are transferred into that innocent person’s possession without his or her knowledge.” Id. However, this critique is clearly not valid under the current construction of the statute. As the court in Maestas v. State makes clear, the Florida statute in question “makes possession of a controlled substance a general intent crime, no longer requiring the state to prove that a violator be aware that the contraband is illegal.” Maestas v. State, 76 So. 3d 991 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2011) review denied, 104 So. 3d 1085 (Fla. 2012). That is to say, the state still must prove that an individual knew he/she was in possession of the substance; just not its illicit nature. Aside from the fact that any notice concerns are ameliorated by the availability of an affirmative defense (discussed infra), this construction of the statute eliminates the type of notice issue this Court was concerned with in Lambert. 20 Team #9 In Lambert, this Court held that a municipal code that required convicts to register with the local government in Los Angeles no more than five days after entering the city violated due process because there was no way for convicts to know of the requirement before entering the city. The statute criminalized behavior—merely being in a city—that is presumptively innocent. Amendment Section 893.101, in eliminating mens rea for Section 893.13 offenses, is not analogous to the statute in Lambert because knowingly possessing the types of the drugs Section 893.13 regulates—things like pills, powders, etc.—is in itself behavior that the average individual should be on notice about as items that the government regulates. Thus, Amendment Section 893.101 does not violate due process as set out in the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution because our federal system of government, in affording great deference to individual states’ broad police power, has translated into this Court refusing to invalidate state criminal statutes on due process grounds in all but the most egregious of violations. Here, Florida’s interest in regulating rampant drug use within its borders constitutes a permissible use of its police powers. Amendment Section 893.101 creates a general intent crime that criminalizes behavior that individuals are on notice as to the government’s interest in regulating. Moreover, even assuming that the amendment eliminated all mens reas as to certain drug crimes, the availability of an affirmative defense denying knowledge of the illicit nature of the substances regulated, discussed infra Section III of this brief, ameliorates any remaining due process concerns. III. The Availability of an Affirmative Defense Eliminates Remaining Objections to Amendment Section 893.101 An affirmative defense provides the accused with the opportunity to concede the elements of the charge, but raise a recognized excuse to justify the violation of the offense. As 21 Team #9 previously discussed, “it is normally within the power of the State to regulate the procedures under which its laws are carried out, including the burden of producing evidence and the burden of persuasion.” 16 Fla. Jur. 2d Criminal Law § 129 (2013). Amendment Section 893.101 provides the accused with the opportunity to assert its “lack of knowledge of the illicit nature of a controlled substance” as an affirmative defense to the offenses listed in Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893. Fla. Stat. Ann. § 893.101(2) (West 2002). Since the “lack of knowledge of the illicit nature of a substance is distinct from lack of knowledge of the presence of the substance,” Amendment Section 893.101 retains the government burden of proving the accused knew of the presence of the substance. Maestas v. State, 76 So. 3d 991, 994 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2011). Amendment Section 893.101 requires the government to rebut the accused’s assertion of lack of knowledge of the illicit nature of the substance, provided the accused raises the affirmative defense. As a result, Amendment Section 893.101 alleviates Due Process concerns because it: (1) disqualifies the statute as a strict liability crime; and (2) does not inappropriately shift the burden of proof onto the accused for an element of an offense. A. Lack of Knowledge Defense Proves Legislature Did Not Intend to Create a Strict Liability Crime The availability of an affirmative defense of lack of knowledge precludes the offenses listed in Florida Section 893 from becoming a strict liability crime. The Staples Test prohibits strict liability for certain crimes when penalties are substantial or when the conviction carries social stigma. Staples v. United States, 511 U.S. 600, 601 (1994). The Staples Court held it would be a violation of Due Process if the government “would impose criminal sanctions on a class of persons whose mental state…makes their actions entirely innocent.” Staples at 601. 22 Team #9 Here, Amendment Section 893.101 explicitly provides for an affirmative defense of lack of knowledge and “because lack of knowledge is not a defense to a true strict liability crime, the availability of the affirmative defense in section 893.101 undermines the essential premise in Shelton that the offenses in section 893.13 are strict liability crimes that may not be constitutionally punished as felonies.” Flagg v. State, 74 So. 3d 138 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2011). Amendment Section 893.101, therefore, is compatible with the holding in Staples since it does not create a “true strict liability crime.” Id. B. The Government Bears the Burden of Proof for the Elements of the Offense and Bears the Burden of Proof to Overcome an Affirmative Defense Amendment Section 893.101 does not inappropriately shift the burden of proof upon the accused. The Due Process Clause provides protection for “the accused against conviction except upon proof beyond a reasonable doubt of every fact necessary to constitute the crime with which he is charged.” In re Winship 397 U.S. 358, 364 (1970). However, an affirmative defense does not impose a burden on the accused to prove an element of the offense, because “an affirmative defense does not concern itself with the elements of the offense at all; it concedes them.” Scott v. Cohen, 568 So.2d 49, 51 (Fla. 1990). This Court has largely upheld state legislative policy decisions to permit affirmative defenses and have not found a violation of the Due Process Clause. Patterson v. New York, 432 U.S. 197, 210 (1977); Martin v. Ohio, 480 U.S. 228, 229 (1987). In Patterson, this Court upheld a New York statute permitting extreme emotional distress as affirmative defense to a murder charge against a due process challenge. The Patterson Court found “the Due Process Clause, as we see it, does not put New York to the choice of abandoning those [affirmative] defenses or 23 Team #9 undertaking to disprove their existence in order to convict of a crime which otherwise is within its constitutional powers to sanction by substantial punishment.” Id. In Martin v. Ohio, the U.S. Supreme Court determined to “follow Patterson and other of its decisions which allowed States to fashion their own affirmative-defense, burden-of-proof rules.” Martin at 229. The Martin Court upheld an Ohio statute permitting self-defense as an affirmative defense to a murder charge against a Due Process challenge: “We agree with the State and its Supreme Court that this conviction did not violate the Due Process Clause. The State did not exceed its authority in defining the crime of murder as purposely causing the death of another with prior calculation or design. It did not seek to shift to Martin the burden of proving any of those elements, and the jury’s verdict reflects that none of her self-defense evidence raised a reasonable doubt about the State’s proof that she purposefully killed with prior calculation and design.” Id. at 233. Drawing upon this Court’s holdings in Patterson and Martin, an affirmative defense does not improperly impose a burden onto the accused and therefore does not violate the Due Process Clause. Here, the government must still prove the elements of the crimes as listed under Florida Section 893 and prove the accused knowingly possessed the illicit substances. If the defense is raised, the state must still prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the accused knew the illicit nature of the substance. Indeed, Florida Standard Jury Instructions direct the jury to find defendant not guilty if they “have reasonable doubt on the question of whether (defendant) knew of the illicit nature of the controlled substance.” Fla. Std. Jury Instr. (Crim.) 25.7. Secondly, the State’s affirmative defense resembles the affirmative defenses considered by this Court in Patterson and Martin. Amendment Section 893.101 does not “require the defendant to establish his innocence by proving a lack of knowledge… rather, the statute 24 Team #9 provides that if the defense is raised, the state has the burden to overcome the defense by proving beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant knew of the illicit nature of the drugs.” Flagg v. State, 74 So. 3d 138, 140 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2011). Since the government still carries the burden of proof for the elements of the crime and must rebut the affirmative defense, Amendment Section 893.101 is a valid exercise of the State’s police power, is consistent with Due Process protections, and this Court’s precedent. 25 Team #9 CONCLUSION For the reasons set forth, the State of Florida respectfully requests that this Court uphold the rulings of the intermediate appellate courts of the State of Florida in their findings that Florida Statute §893.101 is not unconstitutional. Respectfully submitted. Attorneys for Respondent, The State of Florida 26